A Writer Writes — “The Cotton Trenches of Uzbekistan”

by Beatrice Grabish Hogan (Uzbekistan 1992-94)

Dispatch from Uzbekistan’s cotton campaign

November 1993

On the fifth day of barf (Tajik for “snow”), the troops surrendered. The war, a.k.a. the cotton harvest, lasted eight weeks this year and yielded (only) 87% returns.

I had watched my students pile into a 25-vehicle motorcade and wind around the mile-long university boulevard amidst handkerchief waving and cheers from teachers and other onlookers. Two days later, much to the horror and surprise of my women colleagues at Samarkand State University, I joined the students’ work camp.

On October 5, I arrived at the collective farm called Guzelkent, about 40 kilometers outside the city limits. The place was a collection of brown-streaked, whitewashed houses made of mudbrick, rising like Oz out of acre upon acre of cotton fields. It was a scene framed by purple mountain peaks and a flawless blue sky.

At daybreak, I marched to the fields with the students. My fellow domla (teacher) was a cotton vet himself and showed me how to supervise the student brigade. The rows of cotton all looked the same and it was difficult to pick out my own students from the brightly colored hunched-over backs.

My colleague’s well-trained eye spotted them. “There they are!” he said, “just like the enemy hiding.” And there sat three Uzbek girls, their white kerchiefs bobbing at boll level with the cotton stalks. The women looked like mummies as they picked the cotton, their mouths and noses wrapped with gauze. The men’s faces were unprotected. Crop dusters disgorged defoliants which shriveled the greenery and exposed the cotton for clean picking. A yellow residue remained on the cotton. Hearing the advancing buzz of the plane, I ran and hit the deck, covering my head. Everyone laughed and the domla reassured me it was “only salt.”

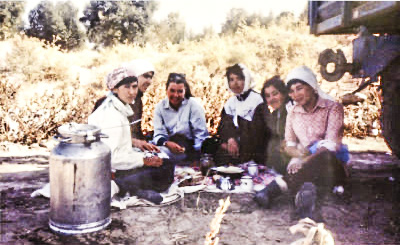

At lunchtime the brigade assembled on the sidelines, huddling around a wood-burning samovar. One student was designated “cooker” for the group and spent the whole morning fetching water from the community well, gathering food, and mixing up a pot of potato or macaroni soup. Before eating, students weighed in their cotton, hooking their bulging aprons onto a wooden tripod with a sliding rule scale. Each sack contained up to twenty kilos. (Students strove to meet a 100-kilo quota per day.) After the tally, the cotton was tossed onto a rising mountain and then picked up by a flat-backed truck and carted away. Meanwhile, it’s a luxurious perch for the domlalar and collective farmers, who dined atop the cotton as the students sat on the ground sharing one bowl of soup among six and passing around a cup of tea.

I expected the students to grumble about the conditions, as I knew American students would. But instead of rebellion, there was an overwhelming sense of resignation at the camp: the cotton is here to be picked and we were there to pick it. University studies span five years instead of four, so the students can spend a full year picking cotton during their tenure. The government orchestrates the effort, and every night, President Karimov appears on national television to read each region’s returns like a roll call of war dead.

Cotton Pickers of Uzbekistan

Students are quick to defend their Republic, saying that ok otin (“white gold,” as cotton is known) is the only currency that Uzbekistan has right now. They pick for future generations. Picking is a rite of passage: their parents and grandparents picked, and so will they. For the collective farmers, I was the first American that they had ever seen, much less the only American to participate in this government agriculture campaign. Villagers peered at me, grade-schoolers touched me to make sure I was real. One group of tenth-form students shyly approached me to give me a handful of walnuts and a piece of bread. Mekmonlar (guests) are treated with the utmost care and respect in Central Asia. My own students displayed their hospitality by giving me the thickest slabs of kielbasa and bread, though they had next to nothing to eat themselves.

I slept with nine of my fourth-year Uzbek girls in one room. At the end of the day, we dined on the bedroom floor. And after dinner, vanity ruled. Preening in hand-held mirrors, some girls rolled their bangs in curlers, others bridged their brows together with black paint. Some girls read, others knitted, and a few boogied to a boom box in the corner. I felt as if I had parachuted into a “Grease” slumber party, Uzbek-style. Boys were on everyone’s minds. All of my students were to marry the following spring, though none knew their future mates.

Communal living was intense. My back ached, my skin burned. The squatton was located in a sheep stable outback. No baths, no gas, no beds. The students slept on collapsible cots, the same contraption that I mistook for a chaise lounge at GUM, the department store in Samarkand.

Uzbekistan no longer belongs to Russia. My friend Ulugbek told me, “Our Republic is just a baby and we must teach it to grow up.” But cotton monoculture is firmly entrenched. Irrigation networks drain the feeder rivers to the Aral Sea, and cotton flourishes in a desert. University students pick it. I teach English. And so life goes on.

•

Bea Grabish Hogan (Uzbekistan 1992-94) is a writer and editor who lives in New Jersey with her family. Her time in Uzbekistan spawned a lifelong interest in the region, and she eventually got her masters in international affairs at Columbia University, with a regional focus on Central Asia. In 2001, she traveled back to Uzbekistan on a journalism fellowship and visited her old friends in Samarkand.

This essay was originally published in Peace Corps Times, No. 1, 1994 and later anthologized in the 1996 essay collection At Home in the World, one of four books of RPCV essays edited by John Coyne and published by the agency.

Bea—-thanks for this insight into a small sliver of Peace Corps life in Uzbekistan—a very unique part of the Peace Corps world.

In the early 2000s I visited Uzbekistan as part of my work with an NGO—was amazed by the architectural wonders of Samarkand but also the miles and miles of cotton fields (Did the kids in the Karimov family join the cotton-picking brigades?).

Interesting fact—the growing of cotton in Uzbekistan came about in the 1860s as a result of the American Civil War, when southern US cotton was blockaded and could not reach Europe. The Czarist government saw “gold” in that white gold, and directed that the Central Asian steppes be brought under irrigated cotton production, to meet the world’s demand for cotton cloth—and so it is there to this day, triggered by totally unrelated events half way around the world!

Thanks for serving the students of Uzbekistan and America by joining the Peace Corps. I did the same in India in 1963-65.

Thank you, John. I don’t know if the Karimov girls picked cotton, but somehow I doubt it:)

Fun fact: Islam Karimov was actually from Samarkand. He attended School No. 21 right behind the Registan. I’m not sure if any PCVs wound up teaching there, but I opted for the university.