A Writer Writes — “House Building On Rapa Nui” by Michael Beede (Peru)

House Building On Rapa Nui

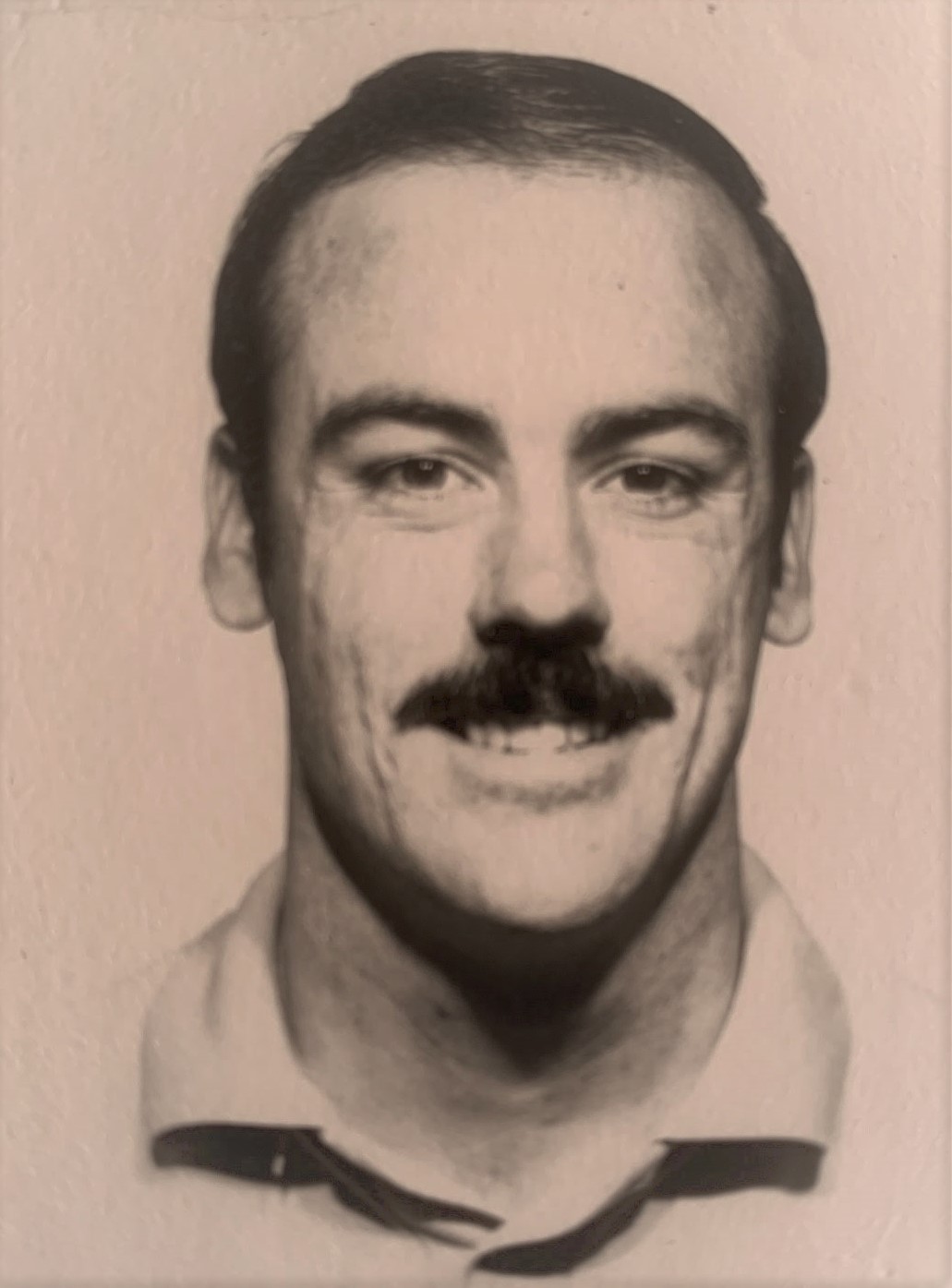

By Michael Beede (Peru 1963–65; Venezuela (1968–70)

•

Rapa Nui, Te Pito Te Henua,The Navel of The World, Isla de Pascua, Easter Island. These are a few of the names of this enigmatic 65 square mile speck of land in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. For centuries it has irresistibly drawn the imaginations and souls of adventurers and dreamers to its rocky shores. I was one who fell under the magical spell of Rapa Nui.

When Noemi, my partner, her four-year-old son, Ali, and I returned to Rapa Nui in 1974, the Islanders greeted us as rich and conquering heroes. When that did not turn out to be the case, the welcome began to wear thin. Locals then saw us as poor Pascuenses, bums, creatures lower than homeless beggars.

In Hanga Roa, the Island’s only village, we shuffled from relatives and friends to other friends and relatives. At first, we stayed in one room of the house of a gay Chilean friend who had rented the place from one of Noemi’s many relatives. The old Pakarati family compound in Hanga Roa was a block away on the unpaved road that climbed the steep hill leading out of the village. At least, we would be in familiar territory. And the arrangement was only temporary until we got our own place.

Nevertheless, the situation rapidly began to unravel and became unbearable for all concerned. Noemi, curiously examining her breasts one morning, announced that she might be pregnant with the soon to arrive Rita Te Ra’a. And so it was. With that upcoming blessed event close at hand, we would shortly need more than a single room to house us all. This unexpected but undeniable fact launched us on a frantic quest for more suitable accommodations.

Another of Noemi’s many cousins graciously offered us the temporary use of half of his house while we searched. His humble dwelling was situated on a hill above the restored Ahu Tahai and afforded a spectacular view of Rapa Nui’s rugged coast. We were now on the very edge of town. Only the cemetery separated us from the Island’s rocky shore and the vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean beyond. Future housing options were nonexistent, but first things first.

My immediate reaction to Noemi’s announcement of her pregnancy was that it wasn’t me. The assumption was absurd because, of course, it couldn’t have been anyone else but me. We weathered out the pregnancy and joyous birth of Rita Te Ra’a at the cousin’s house until that situation also became untenable.

This time, we decided, under Noemi’s wise guidance, that enough was enough. We would no longer live under somebody else’s roof and tyranny. We would stake out our claim, build our own house, and live humbly but free. Just how we were to accomplish that, I did not know because we were almost flat broke.

Those considerations didn’t bother Noemi. She went down the next morning to the government offices in Hanga Roa and filed a claim for the five hectares of land that were the exclusive birthright of all native-born Islanders. She selected a property located at a place called Vai Piki Hiri Hiri. High up on the slopes above the restored Ahus of Hanga Ki’oe, the parcela overlooked the open infinity of the Pacific Ocean. The area was beautiful beyond compare in its near-pristine state.

Noemi’s parcel bordered on the unpaved road that led out of Hanga Roa through the vacant countryside to the Island’s Leprosarium. Except for the scattered archaeological remnants of Rapa Nui’s past, the land’s natural beauty was yet unscarred by civilization. There were no nearby houses, no running water, no electricity, no sewer, no conveniences, contemporary or otherwise. Nothing but hard work lay ahead and plenty of it. To be sure, carving out our homestead would not be an easy task, but it promised to be a labor of love.

Noemi put me right to work as the building project’s chief “go for.” I had no prior experience in logistics or construction and was shooting in the dark. Nevertheless, needs foster solutions, and I soon perfected the art of the scrounge. The secret to my success was that I did whatever my partner patiently told me to do, and it always worked out.

My first mission was to gather 60 empty metal oil drums from the many left behind by the United States Air Force during its brief tenure on the Island. The USAF billed its operations as an Ionospheric Observation Center. But more likely, it was keeping an eye on French nuclear testing on the Mururoa Atoll in the 1960s and 1970s. As well as intercepting low-frequency Soviet submarine radio traffic in the area.

The US Air Force contingent beat a hasty retreat off the Island following Socialist Salvador Allende’s narrow victory in the 1970 Chilean presidential runoff. By then, the Rapa Nui Islanders were accustomed to the seemingly endless supply of US goods and services that flowed on to the Island aboard US Air Force C-130 Hercules cargo planes. The USAF’s sudden departure in 1971 left the Island reeling in a post materialistic stupor from which it has never recovered.

Many of the used drums were in the hands of Noemi’s myriad siblings, cousins, uncles, aunts, and associates. I was to collect as many drums as her relatives and friends would give up. We stored them at the Pakarati compound in Hanga Roa in a closed, secure area, safely out of the reach of other thieving friends and relatives.

Noemi next handed me a single left-hand, worn out, work glove, a five-pound hammer, and a foot-long section of a discarded car spring leaf sharpened at one end. These were the tools of my new trade. Included were her one-time-only instructions in the conversion of empty used steel oil drums into metal wall siding. First, remove the tops and bottoms of the empty drums using the sharpened car spring blade and the five-pound hammer to cut around the inside rim of the drum ends.Then using the same tools and techniques, cut down the drum seam. Splay the cut drums on the ground and stack them as you went. The increasing weight of the piled sheets aided somewhat in the flattening process.

Although this procedure rendered the sixty drums into open sheets, there was still a pronounced curvature in the middle of each one. The solution to this problem required a more heavy-duty mechanical approach. Not to worry, Noemi always had another relative in high places to help out. Sure enough, she had a cousin who was in charge of the steamroller used in airport maintenance at Mataveri.

I borrowed a truck for a couple of hours from my boss, Dr. Bill Mulloy. Bill had the vehicle on loan from the Island’s Public Works Department for the daily movement of his workers to and from the Orongo archaeological restoration project on the Rano Kao Volcano. And so on and on it went. Familial relationships of one kind or another were the currency of the realm that got things done on the Island.

Next came the loading and transporting by truck of approximately one ton of semi-flattened steel siding from the Pakarati compound in Hanga Roa to the airport in Mataveri. This task was demanding, tedious, and time-consuming. The rush to get the job done before our truck loan ran out led to much finger smashing and numerous expressive epithets. Noemi, heavy with child at the time, could only supervise in the loading. The truck driver, two helpers, and I loaded the semi-finished metal sheets onto the flatbed truck, and off we went to the airport.

Noemi had instructed me to ask her cousin at the airport if he would mind flattening a couple of drums for her, which he agreed to do. At first sight, her cousin’s jaw dropped in disbelief at the 60 semi-flat metal sheets laid out for final treatment. Once he got over the initial shock, he walked over to the steamroller and, with a casual shrug of acceptance, fired it up. One pass of the machine was all it took, and the whole lot of metal sheets was flatter than a pancake.

My couple of hours truck loan was running out fast. We still had to get the finished metal siding reloaded on the truck, out to the construction site at Vai Piki Hiri Hiri, and unloaded. Then race back across town past the airport at Mataveri and up the Rano Kao Volcano road to Orongo to return the borrowed truck. The site of the Birdman Village restoration project at Orongo was up on the seaward crest of the Rano Kao Volcano. If we hurried, we’d just make it in time to pick up the crew before the end of the workday and get them home for dinner. We did, and I was learning fast the Island way of getting things done. Island engineering and the coconut telegraph triumphed again.

Noemi then dispatched me to solicit the Tourist Hotel for the discarded wooden crates used to ship bottled wine from Chile to the Island on the yearly supply ship. Why? For the nails that held them together, of course. I extracted each nail painfully, one by one, using an old cast-off hammer and a block of wood for leverage. Then I straightened the nails as best I could by pounding them out on a piece of wooden board. My back ached, and mashed thumbs throbbed for days afterward.

Noemi next sent me on horseback with an ax and a length of rope to ask an aunt’s permission to cut trees from her nearby grove of eucalyptus. The posts would be used to frame the new house. The trees were ideal for our purpose. Tall, slender, and straight, 5 or 6 would do. I felled the trees with the ax, trimmed off the branches, and lashed the trunks together with the rope. I secured the line to the pommel of my war-surplus Chilean Cavalry saddle and dragged the whole bunch to the adjacent building site at Vai Piki Hiri Hiri. There we cut the logs into uniform 8-foot framing uprights. To prevent rot when planted in the ground, we dipped the butt ends of the posts into a half barrel of asphalt tar scrounged from yet another uncle.

Noemi secured, free of charge, a couple of loads of crushed red scoria, a compacted volcanic ash called Hani Hani in Rapa Nui. The material was mined from the Cerro Tararaina, a Pakarati family holding near the Mataveri airport. The Islanders used crushed Hani Hani as a fill in road building and general construction. We used it as foundation fill for our new home in Vai Piki Hiri Hiri. The material was loaded and trucked to our parcela through the good graces of a relative who worked in the Island’s Public Works Department.

We gathered a load of kejo, shale slabs, on the coast where it had sloughed off an eroding cliff face and piled up on the beach below. We transported the slate by ox-cart express to our homestead building site and used it to add a dash of style to the kitchen floor.

The last $150 left in our cash stash went to the ECA government store in Hanga Roa. We bought 15 corrugated metal sheets for roofing, 15 sacks of cement to pour the floor, and an assortment of nails, paint, and brushes for the building’s finishing touches. You had to get these things while the getting was good. Supplies were limited, quickly depleted, and the next supply ship from Chile was a year away.

Father Dave, an American Catholic priest from Long Island and Rapa Nui’s pastor, was a friend of mine. He gave us the discarded rain gutters and massive wooden planks left over from the remodeling of the church rectory. I made several trips from Hanga Roa to our parcela carrying this precious booty on my back. What the hell, I was 33 years old, young, dumb, and full of vigor. I could take it in stride and with pleasure. Once our corrugated tin roof was in place, we hung the cast-off gutters from the eaves with salvaged baling wire. The resulting system channeled fresh, potable rainwater into water storage barrels converted from discarded oil drums. The massive planks became the shelves and counters of our kitchen.

The roofing trusses were eucalyptus tree branches, none of them straight. This donation came compliments of Joel Huke, whose grove was near our parcela. The roofing was engineered and erected by Noemi’s brother, Nicolas Pakarati. Nico, like his father, Santiago, was well versed in the ad-lib arts of Island survival and one of the Island’s premier musicians and songwriters. Noemi rejected out of hand the suggested plebeian slant roofed pai pai structure first proposed. Nico complied, installing a perfect peaked roof with the rustic materials at hand, as demanded by his sister.

All transport of materials and people involved in the project was by foot, horseback, ox-cart, and the occasional loaned Obras Publicas truck. Except for the corrugated metal roofing and cement for flooring, all other miscellaneous construction materials were graciously donated or scrounged from friends and relatives.

I had two good horses on loan from the 5,000 that freely roamed the Island. We had two saddles and the tack essential for Noemi and my transportation. I had a pair of sturdy work boots I’d brought with me from the States, two good feet, and a woman who knew just where we were heading. Who could ask for anything more?

Aside from the formalities of Noemi’s official petitioning for her birthright of five hectares of land, there were no costs, no building codes, permits or inspections. Nor were there any water, electricity or sewage permits, bills, or taxes. There were no out of pocket expenses other than our last $150 spent on roofing and cement for flooring. All that remained of our cash resources were empty pockets. Mind you, it was a no-frills life, but you were free to do as you wished within reason or could get away with, and we did.

We built the house Island style. Friends and relatives participated in the labor, as well as in the umu pai feast that followed. Noemi dispatched me to get the monthly sheep ration of a relative that worked at the Vaitea government sheep ranch in the center of the Island. We dug a shallow pit for the umu pai earth oven and piled it high with volcanic rock and firewood. Friends brought banana fronds essential to wrap and insulate the food during the cooking process. Nico lit the fire to preheat the volcanic stones in the pit to the white-hot temperature necessary to slow cook all the ingredients in the earth oven.

The guests arrived in the morning, bearing donations for the feast. The butchered sheep had been cut up in pieces and wrapped in small banana leaf bundles for cooking. There was poi, a pudding made from a paste of boiled squash, sugar, and flour, wrapped in banana leaves and baked in the earth oven. Topping off the list of ingredients for the communal feast were cumara, Island sweet potatoes, yams, taro, squash, bananas, sugar cane, and pineapples.

Those attending to the umu pai took the white-hot volcanic stones out of the fire pit with shovels and swatches of banana fronds serving as protective hot pads. They set the heated rocks alongside the fire pit with the remaining red glowing coals of the heating fire. Then in alternating layers of superheated stones, banana leaves, cumara, taro, mutton, and poi were laid down in the pit. A final overlay of banana leaves covered with earth formed an airtight seal over the umu pai where the ingredients baked for the next three hours.

While the food cooked in the earth oven, some of the guests worked mixing cement and pouring floors. Others set posts and framing, raising high the roof beams and hammering the painted black metal wall siding into place. The completion of construction signaled the ceremonial opening of the umu pai.

Guests served guests the succulent fare on banana leaves spread on the cleared ground, and the feast began. Some had brought beer and wine, but most of us drank all the good, sweet rainwater we could hold. We all shared in the satisfaction and good spirits of a job well done. There was great cause for celebration. With the arrival of Rita Te R’a, the newest member of our family, the three of us were now four. We had our own house and sheltered under our own roof and were no longer looked down upon as poor Pascuenses or bums. We were free. Congratulatory shouts in Rapa Nui echoed through the feasting crowd. “Ko oti a te anga.” [The work is done.]

•

Returning to Venezuela in 1969 Michael Beede (Peru 1963–65) & Venezuela (1968–70) worked for the Daily Journal, an English language newspaper. He then lived and worked on Chile’s Easter Island from 1972-75 in archaeology and monument restoration for the University of Wyoming. Returning to Venezuela in 1978, he worked as a Drilling Fluid Engineer for the next ten years. He currently lives in Venezuela where he retired in 1999 and is writing his memoirs.

All rights reserved. This essay or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the author.

No comments yet.

Add your comment