A Writer Writes — “Rhythm of the Grass: Letters from Moritz Thomsen” by Mark Walker (Guatemala)

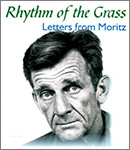

Rhythm of the Grass: Letters from Moritz Thomsen

by Mark D. Walker (Guatemala 1971-73)

Moritz Thomsen (Ecuador 1965–67) was an extraordinary writer and influential expatriate who spent thirty years in Ecuador studying the culture and identifying with whom he lived. His first  book, Living Poor, is ranked as one of the premier Peace Corps experience books, with editions in the U.S., UK, Germany and France. It has sold over a hundred thousand copies in the U.S. alone. All four of his remarkable books have been compared to the works of Paul Thoreau and Joseph Conrad.

book, Living Poor, is ranked as one of the premier Peace Corps experience books, with editions in the U.S., UK, Germany and France. It has sold over a hundred thousand copies in the U.S. alone. All four of his remarkable books have been compared to the works of Paul Thoreau and Joseph Conrad.

Although Thomsen only wrote four books, he was an avid letter writer. His missives numbered in the thousands, though according to one letter, he was only able to respond to five letters a day on his typewriter, often in the hot, humid jungle of Ecuador. According to author Tom Miller, Thomsen was a “wicked” literary critic, “. . . the severity of one letter from him could often take days before its impact wore off.” And yet, despite his propensity for separating himself from the outside world — or perhaps because of his isolation — he corresponded with numerous authors, publishers, and professionals, but mostly with fellow Peace Corps and Returned Peace Corps Volunteers.

He would often correspond with someone for up to twenty years, making them “family.” He shared many of his fears and concerns as well as his day-to-day activities not found in his books. And, in a letter to the family of Joe Haratani, he gave another motivation:

Dear everybody: The impulse to write you all the time, but nothing to say especially. So you don’t have to read these if you don’t want; it is mostly therapy for ME . . ..

These marvelous letters and the attendant chronicle of the relationships that developed over their course make for a story that is both fascinating and moving.

Thanks to author Tom Miller, I gained access to five boxes of letters and sketches of Thomsen, which Miller had donated to the Special Collection at the University of Arizona. I used these to research several articles on Thomsen, but after my article on Living Poor was published in the 2019 Winter Edition of WorldView Magazine, I was inundated with a staggering number of new letters.

A Deluge of New Thomsen Letters

The deluge was initiated by Returned Peace Corps Volunteer Todd Tibbals, who had been a Volunteer in Peru, then worked for the Peace Corps as a Regional Director in Ecuador, and an Ecuador Desk Officer in Washington. Today he’s an accomplished artist living in New Mexico. Tibbals contacted me to say that he liked my article, and, after a brief chat, he sent me two of his letters from Thomsen plus a “mother lode” . . . 215 pages of letters from a former Peace Corps/Ecuador Country Director, Joe Haratani.

Tibbals had met Thomsen in Ecuador, and in 1969 saw him again at the Dot-S-Dot Ranch training center in Montana, where Tibbals took a picture of him with an oil painting Thomsen had just completed (a revelation to me since I thought he’d only done sketches).

Tibbals had met Thomsen in Ecuador, and in 1969 saw him again at the Dot-S-Dot Ranch training center in Montana, where Tibbals took a picture of him with an oil painting Thomsen had just completed (a revelation to me since I thought he’d only done sketches).

Thomsen had actually called Tibbals after leaving San Francisco for the training center in Montana to joyfully inform him that all his “worldly possessions” were stolen from his old vehicle: “Hey, Todd, I’ve finally been LIBERATED!”

Tibbals’ first Thomsen letter, from September 17, 1970, starts:

I put my hand in the envelope, pulled out a letter to answer and lo and behold, T. Tibbals’ name led all the rest [which Thomsen reveals numbered 329 letters]. Aren’t you the lucky bastard?”

He tries to convince Tibbals to visit,

Well, I’ve been waiting for you, honey; wasn’t it THIS summer you were coming down to give me some art lessons in exchange for board and room? Jesus, another snow artist. I swear. I’m glad now I didn’t build you a special guest house; wouldn’t I have felt like a fool?

The focus of this letter then moved to a darker direction:

Here we are stuck in the jungle with all our money invested in 20 acres of peanuts (which are about to be eaten by worms), everything in a state of perpetual crisis, trips to Esmeraldas every day to buy plugs to keep the ship from sinking. And I had a very different kind of life planned, believe me . . .. Ramon started screaming at dinner tonight . . . this is no life for me, I had this modern farming, the battery dead, the radiator with holes, the hydraulic plugged up, the bovina falling off the light plant, out of kerosene, out of gasoline, out of diesel . . .. And God knows I sympathize, but we’re in too deep now to relax for another five or six months . . .

Tibbals was surprised to receive a second letter ten years later because they hadn’t been in contact, “maybe because I felt he was already a celebrity, and would hardly remember me.” In this second letter, Thomsen provided a literary update of sorts on his third book, The Saddest Pleasure:

Just finished another book — a masterpiece on three levels, travel in Brazil — which reminds me of the farm in Esmeraldas which reminds me of my family and their robber baron ways . . . a kind of investigation of the northern presence down here and that ends up lashing out at PC (Peace Corps), the world bank, the Christers, etc. . . .. Nobody likes it very much; it has been rejected by Sierra Club, Random House, and my ex-publisher, Houghton Mifflin . . . . Screw them all.”

He ends with:

Todd, keep selling my book, for Christ sakes . . .. My mother is my only reader in the US of A . . . . All that fucking work por gusto . . . why does anyone want to write???? Except letters . . ..So YOU write, o.k?

Joe Haratani’s Compilation

Joe Haratani was a former Peace Corps Volunteer who met Moritz Thomsen in 1968, after leaving USAID’s bureaucracy to rejoin the Peace Corps, covering the Pacific coast of countries in South America. They further developed their friendship after Haratani was named Peace Corps/Ecuador Country Director.

Joe Haratani was a former Peace Corps Volunteer who met Moritz Thomsen in 1968, after leaving USAID’s bureaucracy to rejoin the Peace Corps, covering the Pacific coast of countries in South America. They further developed their friendship after Haratani was named Peace Corps/Ecuador Country Director.

Over the last twenty years of his life, Thomsen wrote letters to the entire Haratani family. Joe Haratani compiled all these letters and included commentary before each section of letters and photos about Thomsen’s “ever changing life and work,” which provided a frame of reference by describing what was happening with his family’s life at the time. He ended his compilation with a biographical sketch and a sentimental and emotional postscript:

When Moritz died, so did a part of our life. We think of him often.

One letter from 1972 revealed that Thomsen was driving his Datsun pickup to Quito when two huge banana trucks came barreling around a curve on the narrow two-lane road, racing to pass each other, and flattened the pickup and badly injured Thomsen. A passerby contacted the Peace Corps office, which sent out an ambulance and took him to the hospital, but the accident had crushed one of his lungs. This, plus Thomsen’s addiction to cigarettes for much of his adult life, would cause long-lasting health issues.

Haratani took the name of his compilation from a phrase in one of Moritz’s 1972 letters, “rhythm of the grass,” which came about when the two couldn’t find a good answer to a question Moritz asked, and Haratani blurted out, “It’s the rhythm of the grass,” a phrase only the two of them knew. It died when Moritz did, until Haratani brought it to life again as the title of his collection.

Haratani also accepted the responsibility for the foul language that permeated Thomsen’s correspondence. He went on to say:

. . . if you can ignore the vulgarities, you will experience the candid humor and pathos of Moritz’s letters. They reveal a Moritz Thomsen not to be found in his books. This is Moritz Thomsen, warts and all: the reluctant WWII bombardier; the twice-failed hog farmer; the self-effacing humanist with an outrageous sense of humor; the ultimate, self-proclaimed incompetent who succeeds in attaining that most elusive of human goals, that of changing for the better the lives of the people he touched.

A few of the interesting tidbits revealed in Haratani’s letters from Thomsen include an anecdote from revered travel author and friend, Paul Theroux (Malawi 1963–65), who wrote Thomsen about how Jack Nicholson was offered the lead role in the film version of his novel, Mosquito Coast, but wanted $4.5 million, so Harrison Ford got the role. Haratani goes on to say that, “having been born in Hollywood, Moritz continued to keep an ear to the ground for news from home.”

In a letter from September 15th 1978, to Haratani’s oldest son, Richard, Thomsen tells of one of the 25 letters he planned to respond to that day,

. . . [from a] Mr. Shapiro in Hollywood who is trying to make a TV movie out of “livin’ Pore and he is signing contracts for this with the U of Wash. Press. All complicated by the fact that my New York agent insists that only I have the movie and TV rights . . . excitin’ huh?”

The biographical sketch at the end of Haratani’s compilation reveals the strong relationship he had with the author:

Moritz remains in my memory, not because he was an ‘older Volunteer.’ I had met others. Not because he was a ‘super-Volunteer.’ He was not. It was because he became my close friend. I fell in love with that old fart. He was totally unassuming and forgiving while being brutally honest about himself and his frailties. He was so tolerant of others and so tough on himself.

Haratani ended his compilation with a heartwarming narrative to Thomsen, “So this postscript is for you, Moritz.” Haratani continues:

I have one last complaint (and regret). I really wanted you to come up to Sonora and do the Studs Terkel bit, driving a pick-up around the country interviewing folks and writing your impressions of America after your 25-year absence. It would have been fun to have gotten together to talk with you from time to time, getting your low-down on the state of affairs as you saw it. But things didn’t work out that way and I regret that it didn’t. If there’s to be a second time around, I’m going to insist that you go on that hadj and tell me all about it. Mientras, Moritz, rest easy.

Sheilababyhoney

Sheila Gallagher Tiarks is a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer who met Thomsen at Peace Corps training in Bozeman, Montana in 1964. She shared:

He was our class clown. He probably liked to shock people. We twenty-somethings tended to pair up. Moritz at 46 solo-ed. I rarely saw him in Ecuador as I was in the mountains and he on the coast. After my termination in 1966, I never saw him again, but the letters helped. He’s still the most colorful character I’ve ever known.

Tiarks sent me six letters in which “his unique personality comes through.…” Thomsen wrote directly to Tiarks during the 1960s, addressing her as “Sheila-baby” or “Sheilababyhoney” signing off as “Your teen-age idol.”

In one of the letters to Tiark from 1966, Moritz revealed the steps to producing his best known book, Living Poor:

I have been steadily writing for the paper in S.F. (San Francisco) and my friendly editor sent copies of articles to a college chum who is now editor of the Washington press; they wrote last month offering me a contract for a book using the articles — which amazes and pleases me, although I still don’t know what kind of a book they want or if they expect a lot of rewriting etc., crap that I don’t have time for.

A year later, he would update Tiarks on his progress writing Living Poor:

My poor editor in Seattle keeps writing me plaintive letters about working on my book. And there is just no time . . .. Two months ago they were real snotty letters. And then Harcourt Brace tried to publish the book instead and all of a sudden he got real sweet . . .. It is such a job and the first articles are so flippant that I get sick looking at them. Actually, it is always only the last article that I like; the rest all miss the target or they don’t tell the truth or are somehow sentimental or phony. The trouble is, my attitude keeps changing toward this damn country; half the time I want to blow it up with H bombs or divide it with Peru and Columbia; but Hell, they don’t want it.

Despite not yet having published a book, Moritz was already developing a following:

Am getting modest quantities of fan mail, some of them screw-ball, asking for sea shells or seeds, some of them sending money, some from frustrated secretaries saying “your articles inspired me to apply to P.C.”

The most surprising event revealed in Tiark’s letters was Thomsen’s plans to take his black farm partner, Ramon Prado, to California with him:

I had trouble getting Ramon into California with a little pin-headed US consul, and while it didn’t do any good, Erik raised hell trying to help me . . .. Ramon and I went to Quito, made reservations, bought tickets, got passports, etc. And then the consul said Ramon was too poor and probably wouldn’t come back but hide in the States and that I had to get him so we tucked our tails between our legs and came back to Rio Verde where we are now waiting for the boat to arrive. We are going to try again and leave here Saturday . . .. Another bitch. By traveling Ecuadorian airlines we could save enough off the travel order to almost pay for Ramon’s ticket, but no, we have to travel American lines, which will cost me 500 bucks — which I don’t have.

He took Ramon to San Francisco:

Moritz and and Ramon’s two children

It was amazing to see mi pais con los ojos de Ramon (to see my country through Ramon’s eyes), in fact it was frightening; we spent two weeks there out of the month and then in a sort of desperation headed south of the border. A week in Mexico, a day in Cosa Rica, 5 in Panama. Bought a beautiful camera there, which was robbed along with my old one shortly after returning. Ramon was a little prince in California; everyone loved him and spoiled the hell out of him. He told off my sister for letting her husband cook supper one night; after that, she waited on him hand and foot; he accepted this as his due. At a drunken party he told off everyone for screaming and fighting; he was real noble . . . I took him to see “Black Orpheus” at a little art theatre in Palo Alto one night; it cracked us both up — me for about the 3rd time. Also took him to the African ballet and that set him on this ears; the best thing was the anthropological museum in Mexico City. That is really something worth a special trip in itself. What else: Hell, it seems so far away now. I did enjoy traveling with him, though. He came out of the bathroom in Mexico City and said “boy, that water is really hot. I had to keep running over to the water basin to pour cold water on me.” I then showed him how to regulate the hot water.

Skip ten years to March 1978 and Thomsen divulged another surprise to Tiark,

Wish you would write, though I don’t know what the hell you could say from Oklahoma City, though I shouldn’t poor mouth it since I had a very sweet sexual encounter there during the war— not the civil war, the Big One, you know . . .. And two months later I married the wrong girl.

He also provided insights into the publication of his second book, The Farm on the River of Emeralds, which would be published in June of 1978,

. . . by Houghton Mifflin in Boston, and I will be extremely pissed if you don’t buy a copy, read it, and let me know what you think. I don’t know what to think anymore since I have rewritten and rearranged it so much that I don’t know if I will make the tears flood from reader’s eyes; it is a sequel insomuch as Ramon is still the principal character, but it is also about the corruptions that poverty infects people with and it is sort of a confrontation with my ambiguous feelings about negritude . . .. Anyway, I hope you like it and that it makes you cry.

The Last Days

Moritz had a fixation with death, and his declining health impaired his capabilities over the years. After 1983, his letters were increasingly hand-written and as time went by, they became more difficult to read. What might have been his last letter, dated August 1, 1991, came to me from Tom Miller, the acclaimed author and personal friend of Thomsen who saw the “chain smoking Thomsen” with some frequency and formed a personal friendship that continued in extensive correspondence. He set up the Moritz Thomsen Collection at the University of Arizona. This letter was addressed to “Jo,” and we don’t know who this is, but in the last paragraph Thomsen writes,

This sheet was picked up by the wind and delivered to me. I thought I had sent it off weeks ago. It is now the 18th of August. Oh well, I am sick again and too confused to take my pills correctly. The one for dizziness, God, which one is that? I must stop the diarrhea one since the product is coming out like cement. Oh God. What a bummer. Moritz.

According to fellow author and confidant, Mary Ellen Fieweger,

I think he was ready to die, and determined to do it the way he had chosen to live most of his adult life. He died poor, with a disease that affects only the poor.

The last paragraph of Joe Haratani’s “Rhythm of the Grass” provides the most poignant perspective on Thomsen’s state of mind leading up to his death,

So why should he accept the miracles of modern medicine and lose his best chance of dying? He wanted relief from his self-doubts, his imagined failures, his constant self-analysis, his self-hatredthe heroic burdens of his life. No, he would not reject this unexpected gift, no matter how much it would diminish the lives of those who loved him. No, Moritz wasn’t willing to hang around any longer. So, he released himself from the endless struggles of living and left us to wonder why.

These new letters add to a better understanding and appreciation of the fears, tribulations and raw genius of this amazing author. His four books rank him as one of the great authors of the 20th Century, and yet his letters may prove to be his true masterpiece.

•

Mark Walker (Guatemala 1971-73), implemented fertilizer experiments in Guatemala and Honduras, after which he earned an MA in Latin American Studies from the University of Texas in Austin and spent the next 40 years with various international NGOs including CARE International, Make-A-Wish International, and as the CEO of Hagar. His own memoir, Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond, was ranked 39th by Amazon for “Travel, Central America and Guatemala”. Two of his articles were published by WorldView Magazine, including “Living Poor” an essay about Moritz Thomsen’s renowned Peace Corps experience book. He’s writing a series of articles on the immigration crisis in Central America, one of which is about Guatemalan filmmaker and recipient of the Harris Wofford Global Citizenship Award, Luis Argueta and was published in the Revue Magazine. He’s the Membership Chair of the NPCA affiliate, “Partnering for Peace.” His wife and three children were born in Guatemala and all live in the Phoenix area. He can be found at www.MillionMileWalker.com

Bravo, Mark. Hopefully, your articles will evolve into a book. I agree with Thomsen that The Saddest Pleasure was his opus. It is a masterful travel book.

Lorenzo, We’ll see about the book. And “The Saddest Pleasure” is amazing, but when Paul Theroux told me that Thomsen’s master piece might have been his letters–that got me thinking….we’ll see what comes out of the next batch of letters I’m researching and will write about.