A Writer Writes: Bulo Burte Blues

Bulo Burte Blues

by Bob Criso (Nigeria & Somalia 1966-68)

From the moment the plane landed in Mogadishu, I was a stranger in a strange land. I was a lame duck, a refugee from Nigeria. Evacuated during the Biafran War with eight months left of my two years, I was given the option of going to another country in Africa. I chose Somalia. After adjusting to the hot and buggy tropics, I arrived in a dry and sterile desert. Just when my Igbo had become serviceable, I had to try to decipher Somali. Ask me anything about the history of Nigeria and I might know the answer. But Somalia?

My first stop was the Peace Corps office where I overheard a Volunteer yelling, threatening to kill himself if they didn’t get him out of “this fucking country” within twenty-four hours. It was jolting. I was told Somalia had the highest rate of PCV’s who didn’t finish their two year terms but this seemed extreme. Later I went to lunch with a few volunteers who wasted no time in warning me about the oppressive heat, the unmotivated students, the chilly reception I would get from the locals and the poor food once I left Mogadishu.

“Don’t be surprised if some Egyptian religious teacher begins waving pictures of Israeli atrocities at you and starts condemning America” one jaded Volunteer warned me. It was August, 1967, not long after the six day war in the Middle East, and I was in a Muslim country. I had just left the Igbos, one of the most pro-American ethnic groups in Africa.

“And make sure you don’t carry a camera,” another Volunteer added, “or you could be picked up by soldiers or police.” The Soviets were advising the military at the time; the Chinese were advising the police. The Americans had a small, low-profile presence which got bumped up a notch when the Peace Corps arrived. It was the cold war, African style. Were we being used as pawns, I thought?

The setting for this depressing conversation was, ironically, a kind of paradise. We were sitting under a leafy trellis in an outdoor garden restaurant. A soft breeze from the sea rustled the leaves above us. Green plants and flowering vines were sprouting from oversized pots scattered around the yard. Somali men wearing long white robes and caps were sipping dark tea from glass tumblers and talking quietly amongst themselves.

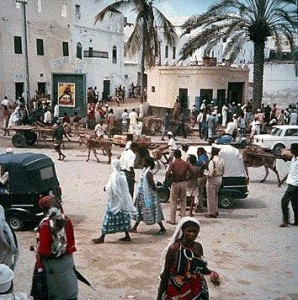

I had already noticed the simple but spectacular beauty of Mogadishu itself; a white city dotted with minarets, spread out alongside pristine beaches and a sparking turquoise sea. I was eating lasagna and a salad that could have been prepared in Tuscany, a reminder of the former colonizers in the southern half of the country. The Somalis themselves were also quite striking. Many were tall and thin with small, even features, caramel skin and fine curly hair. They were among the best looking people I had seen anywhere.

My assignment was Bulo Burte, a small town a few hours northwest of Mogadishu. It was isolated and hardly touched by the outside world. You got there by bus or on the back of a truck that ambled over unpaved roads winding through dry and dusty brush, a little reminiscent of the American southwest. Historically, Somalis were nomads and it was not unusual to pass a family on the road with their portable homes folded on the back of a camel as they searched for the next water hole.

I shared a two room house with Paul, another Volunteer, and we taught all subjects at an intermediate school. The language of instruction was English but the students’ comprehension level was limited as was their enthusiasm for learning. We tried to make the best of it but it was not a gratifying experience. When classes were done, there was little to do and nowhere to go outside of a stroll through town after dinner when it was cooler or a longer walk to the Shebelle River.

People were distrustful of foreigners, especially Americans, so it was hard getting to know the locals. Most kept to themselves, especially the women of course, many of whom were veiled and fearful of any man’s glance. As predicted, an Egyptian religious teacher came up to me on the street one day waving pictures of Israeli atrocities and condemning America. I let him rant and then moved on.

The closest acquaintance we had in town was Mohammed, the man who owned the café where we had lunch (samosas and tea) and dinner (low-grade spaghetti with an oily sauce and goat meat when available.) It was the same menu every day, the only change of diet coming during trips back to Mogadishu and from whatever supplies we could carry back. The daily frustrations of life in Bulo Burte began to take a toll: my weight dropped, my hair thinned and my spirits tumbled.

The best thing about Bulo Burte was the nights. The temperature went down with the sun and the wide sky was flooded with stars. Sometimes I’d lie on the roof, look up at the extraordinary panorama and think about life’s bigger questions while making plans for my return to the States. It gave me some perspective and helped get me through the tougher days. Those same stars have inspired many generations of talented Somalis poets, a fact unknown by most of the world.

The worst part of Bulo Burte was the loneliness. Paul and I were both ethnic New Yorkers who were probably not the coolest kids in our schools so you would have thought we had a lot in common. We didn’t. We bonded anyway but more in a kind of a survival mode rather than friendship. Once in a while he went off on a weekend to see one of his friends but he preferred to go alone. Our only visitor was an occasional drop-in from Mike, a Volunteer working on an agricultural project about an hour or two away. He was one of those golden boys from California whose good looks, worldly savvy and fearless confidence were not only impressive but intimidating.

Although I got to know some of the other Volunteers when I went to Mogadishu, all of my connections in Somalia felt superficial and never filled a lingering emptiness. I felt like a foster child who had been given a temporary home but who was never really part of the family. I longed for the closeness that I felt with friends from my training group and the locals in my Nigerian village. I fell into a depression that was part displaced person, part mourning for the losses of Nigeria and probably part long-term baggage that I brought with me from home. I kept it to myself, put on a good face and crossed off the days until my eight months were over.

When I finally flew out of Mogadishu, I felt like a marathon runner staggering across the finish line. Now it was time to go home and start the reconstruction project. It wasn’t going to be easy: Viet Nam was escalating and I had a 1A from my local draft board, Martin Luther King had been shot and parts of Newark and Detroit had burned down in race riots. It was the spring of 1968 and America was changing even faster than I was.

After returning from the Peace Corps, Bob initially worked as teacher in New York City then later as a psychologist at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and Princeton University. In 1997 he took a year off and boarded a freighter going around the world and started writing about the Peace Corps, Parkinson’s disease and his family. He currently lives in New York City. (bobcriso@gmail.com)

More by this writer, please.

I sure hope there’s more to this beautiful piece.