Mark Wentling: About AFRICAN MEMOIR, 50 YEARS, 54 COUNTRIES, ONE AMERICAN LIFE

by Mark Wentling (Honduras 1967-69 & Togo 1970–73)

The central purpose of my sixth book, Africa Memoir, 50 Years, 54 Countries, One American Life, 1970-2020, is to share my lifetime of firsthand experiences in Africa. I also attempt to communicate my views about the many facets of the challenges faced by each of Africa’s 54 countries. At the same time, I provide some basic information about each country.

This memoir is a reference book that can be read in its entirety or by selecting a chapter on an individual country. I have followed the alphabet in presenting a chapter on each African country. Therefore, I begin with Algeria and end with Zimbabwe. There are also beginning ‘Forward and Overview’ sections, and I end this long book with an ‘Epilogue’ about my dream for Africa.

This book will be of interest to anyone concerned about Africa and its development progress predicament. Anyone working on global affairs and humanitarian assistance to Africa will find the reading of this book important. In particular, people studying Africa or those having had contact with this complex continent will enjoy reading this book. Of course, anyone wanting to get deep inside Africa will want to consult this book.

Below is one chapter of Mark’s book, selected at random. JC Note

•

Ethiopia

I have been to this country several times and I have learned much about it from my wife, who was born and raised in Ethiopia. This abundance of knowledge about Ethiopia does not, however, make writing this chapter any easier. I live with Ethiopia every day, but it has taken me the longest time to even attempt a draft of this challenging chapter.

I really do not know where to start in trying to convey a few of my experiences and share some of what I know about this exceptional country. I fear that anything I write below will come across as an over-simplification and I will leave large gaps in the knowledge of what one should know about this unique country in Africa and in the world. Ethiopia and its long history really defy any acceptable description in a short chapter.

I did not know anything about Ethiopia when I first arrived there in 1983. All I knew then was I was going to the capital city, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia to join a team which was mandated to come up with a scheme for providing thousands of tons of U.S. food aid to tens of thousands of Ethiopians who were on the verge of starvation following a serious period of drought. I had already been in Africa for almost 13 years, so I thought I did not need to know anything more to do my job. I was wrong in thinking like this. I found myself totally unprepared for what confronted me in Ethiopia.

At that time, Ethiopia was like a different planet to me. It was unlike anywhere else I knew in Africa. Certainly, the poverty and hunger of many of the Ethiopians I observed was like I had seen elsewhere in Africa, but the Ethiopians looked different and their customs and language were unlike anything I had known heretofore. I felt lost on a continent I thought was my new home.

This first visit to Ethiopia lasted less than two weeks, but I was obliged to be a quick study and learn something about Ethiopia. I knew very well that the government of Ethiopia was under the iron fist of an unfriendly Marist-Leninist military dictator, Haile Marian Mengistu, who came to power in 1974 by violently overthrowing a world-renown man, Haile Selassie, who had been emperor of Ethiopia since 1916. This bloody dictator was backed by the Soviet Union, which had helped turn the tide in the 1977 Ogaden War against Somalia in south-eastern Ethiopia. This tide was turned in this war in favor of Ethiopia by the Soviet deployment of 15,000 Cuban combat troops.

I learned that one of the challenges of providing food to tens of thousands of Ethiopians on the verge of dying from causes related to extreme hunger was finding ways to deliver food to them without experiencing diversions by the government for their own needs or its sale to generate income to buy weapons. Airdrops of palettes of food grains were scrutinized. This was the most expensive way to deliver food, but it had at least the advantage of being received by some of the people who desperately needed food. It also had the advantage of not being diverted for purposes unrelated to providing food relief to the needy population.

Sometimes it came down to saving starving people by this costlier food delivery method because the government was unwilling to cooperate. I had been involved in the past with assistance efforts because governments were not capable of providing aid, but I had never been involved with a government that was unwilling to help. For years after that, I would always ask myself if a government was limited in what it could do to help because of incapacity or unwillingness, or both.

While I was there, I heard some awful stories about how the reign of the man, Haile Selassie, who had been emperor for over 50 years had ended. This 83-year old man was allegedly strangled to death in his bed by henchmen who were under the orders of the brutal dictator. Later, I heard his body had been found under a slab of concrete that covered a latrine. This ghastly death of Ethiopia’s last emperor marked the end of a line of emperors that traced its lineage back over a thousand years or longer. It is commonly accepted in Ethiopia that its original monarchs descended from a relationship between the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon.

I heard much about how the communist ‘Derg’ regime had killed many people with the violent unleashing of its bloody ‘Red Terror’ campaign. Initially, this campaign started with the execution of people involved with the imperial government and then spread to all those in the capital and everywhere else in Ethiopia for those who were suspected to oppose the cruel regime. The mass killings conducted by the Derg numbered in the tens of thousands.

The regime also used the famine in the northern part of the country to weaken the opposition that existed in this part of Ethiopia. It is estimated that tens of thousands of people died from starvation because of the restrictive policies and actions taken by the Stalinist government. Some estimates show that up to a half-million people died in direct Red Terror killings or from food scarcity purposely caused by the Derg.

For security reasons, I was not allowed to go upcountry or walk around in the capital city during this first brief stay. I, therefore, had to rely on local Ethiopian employees for answers to my questions and information about Ethiopia. They said most Ethiopians are rural farmers who eke out a living by cultivating small farms of less than five acres. Agricultural productivity was low, and the rich soils of the densely populated highlands were being depleted by continuous cultivation. Mixed farming was practiced, but plentiful cow manure was not used to enrich fields but for cooking fuel.

The latter assertion made me think of other African countries where accessing cooking fuel is a major problem, particularly in fast-growing urban areas. What fuel do you use to cook your food? Traditionally, trees were cut, and their wood was used for cooking fuel, or their wood was processed into charcoal that was used as cooking fuel. Rapid population growth has led to a steep rise in the use of firewood and this has resulted in accelerated deforestation. Increasingly, the distance between urban centers and dwindling forests or woods is becoming longer.

The alternatives to using wood or charcoal are limited and more expensive. Many urban dwellers do procure small containers of propane gas for cooking, but that option is more expensive and gas bottles are not always available on the open market. Solar cookers have been tested, but the answer to how the masses can cook their food without the continued removal of trees from the landscape has not yet found an adequate response.

Most of Ethiopia’s rural population live in impoverished conditions. Usually, entire families of six to eight people live in one round mud house and sleep inside with their animals. Children sleep on the earthen floors of these houses. At night, in the vast highland regions (often over 7,000 feet in altitude) of Ethiopia, temperatures average in the 40s F. These cold and damp conditions contribute to several childhood illnesses.

Many children are more susceptible to illness because of their low nutritional status. In general, Ethiopia’s children suffer from one of the highest childhood stunting rates in Africa. I have always questioned how far Africa can advance if a high percentage of its children are physically and mentally permanently diminished by stunting. Good nutrition of a country’s population is the foundation upon which long-term developmental progress is built.

During this first short stay in Ethiopia, I did learn about the importance of coffee in Ethiopian society. I was an active participant in what is referred to as an Ethiopian coffee ceremony. It is difficult to disassociate coffee from the Ethiopian way of life. Arabica coffee originates in Ethiopia and has for centuries been an almost daily part of an elaborate Ethiopian coffee ceremony enacted regularly by families and social groups. Coffee continues to reign supreme in Ethiopia and is its biggest export.

I also learned a bit about Ethiopian food which is different than anything I had experienced elsewhere in Africa. Key to Ethiopian culinary arts is a large, round and type of flat, spongy bread made from teff flour called injera, which is eaten and used to scoop up the spicy stews that are placed on top of it. Teff is a cereal crop mainly found in Ethiopia. Most Ethiopians eat injera every day. There is an Ethiopian saying, “If you have not eaten injera, you have not eaten.”

The traditional dress in Ethiopia is made from white handspun cotton that is often beautifully embroidered. I noticed that many Ethiopian women wear daily clothing. I asked one of my Ethiopian colleagues why women wear these clothes more than men and he said, “Women want to be beautiful.”

I replied, “There are sure many beautiful women in Ethiopia.”

He then ended our conversation by firmly saying, “All Ethiopian women are beautiful.”

I left Ethiopia before the 1984-85 famine had reached its height. I later read that groups of musicians raised money for the hungry in Ethiopia by releasing records for sale. Famous singers contributed to the best-selling works referred to as “We Are the World” and “Live Aid.” Millions of U.S. dollars were raised by these efforts to alert the world to Ethiopia’s serious famine. There was some controversy over whether or not all the money raised benefited those suffering from hunger or if part of this money was diverted into the coffers of the state to buy weapons so it could further suppress Ethiopia’s population.

In 2005, I happened to watch on TV a BBC documentary about a group of journalists revisiting the same places in Ethiopia where they had observed first-hand the horrendous effects of famine on the local population 20 years earlier. They met several people who claimed to have been saved from starvation by food relief. They also met people they had spoken with 20 years previously. I continue to be struck by the concluding statements of this interesting documentary. The journalists were asking each other whether or not many people had been saved from starvation only to become beggars. This conclusion still hits me like a low blow in the gut.

In March 1993, I was able to return for a few weeks to Addis Ababa (flower), Ethiopia’s bustling capital city which was founded in 1881 by Emperor Menilik I. Many of the observations of Ethiopia ten years after my first visit are recorded in a few chapters of my book, Dead Cow Road, which was published in 2017. I, therefore, refer readers to this book for more information about Ethiopia.

Before this 1993 visit, I was able to do the homework on Ethiopia I should have done before I quickly went there in 1983. I learned this was an ancient country whose history goes back several millennia before Christ. It was also predominantly a Christian country with about two-thirds of the population adhering to the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. I read that Christianity had entered Ethiopia in the early times of Christianity and became the official religion of Ethiopia in the 4th century.

Our local Ethiopian priest told me that Ethiopia (or its ancient names of Abyssinia or Kush) is mentioned 44 times in the Bible and that Ethiopia had Christianity long before Europe. It is not possible to disassociate Orthodox Christianity from Ethiopian culture and society. One important thing that distinguishes Ethiopia is the widespread practice of Orthodox Christian religion. The fact that there are more Christians in Ethiopia than there are people in almost any other African country is remarkable. There are only three countries (Nigeria, Egypt, and Congo-Kinshasa) out of Africa’s 54 countries that have a total national population higher than the estimated 75 million Christians in Ethiopia.

The ancient language, Ge’ez, used by the Ethiopian Church is among the oldest languages in the world still in use. It is from this language that Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia, was developed, using an ancient script that is difficult for foreigners to master. It is a Semitic language which in terms of the number of speakers is in second place behind Arabic, another Semitic language.

Another way Ethiopia distinguishes itself is in its use of a solar calendar which is derived from the ancient Egyptian calendar and akin to the Coptic calendar. This calendar is about seven years and three months behind the Gregorian calendar in use in most of the world. Also, Ethiopians use a different way of telling time. They mostly use a 12-hour clock where dawn to dusk is one to 12 and this sequence is repeated for the dusk to dawn period. All this can be confusing for someone coming from outside Ethiopia.

I was happy that a rebel movement dominated by a northern Ethiopian group ousted militarily the Marxist-Leninist dictator in 1991 and was fully in control when I was in Addis Ababa in 1993. Unfortunately, this change in regimes did not translate into peace. Some parts of the country and their ethnic (Ethiopia has over 80 ethnic groups) occupants were protesting the policies of the new government, its human rights violations and contesting the nomination of Ethiopia’s new Prime Minister (in Ethiopia this position is much more important than its nominal president).

One action particularly disliked was the government’s periodic shut down of local media and the internet. Many Ethiopians were having difficulty accepting the rebel movement which overthrew their hated dictator because it was led and dominated by a northern ethnic group which represents less than six percent of Ethiopia’s total population.

It is ironic that during all this political and social upheaval, the former communist dictator was living peacefully in exile in Zimbabwe. This bloody dictator, Mengistu, had been sentenced to death in absentia by Ethiopian courts years ago, but he has yet to be extradited by the Zimbabwean government. There are some hopes that with the death in 2019 of Zimbabwe’s long-term president this former Ethiopian dictator will be extradited and tried for the crimes he committed against humanity.

My reading of the long history of Ethiopia was that it was one filled with a succession of violent conflicts, wars, protests, rebellions, recurrent droughts, and resulting famines. One war was against an invading Italian army in 1896. Ethiopia won this war, but a part of the fascist Italian army invaded Ethiopia and cruelly occupied it with much bloodshed for five years (1936-45) until the end of World War II. Italy intended to create an East Africa colony composed of Ethiopia, Eritrea and Northern Somalia. This occupation by the Italians did not detract from the fact that Ethiopia is one of two countries in Sub-Saharan Africa that has never been colonized. (The other country is Liberia.) Fighting so many battles has contributed to Ethiopia having today one of the largest and most effective military forces in Africa.

When other African countries gained independence from various European countries in the 1950s or 1960s, they often adopted the colors of the Ethiopian flag for their own new national flags. The Ethiopian flag has always had three horizontal bands of different colors. The top band is green, representing Ethiopia’s fertile land. Next under this green band is a yellow band that reflects national wealth. On the bottom of the flag is a red band, indicating peace and faith in the nations. In the center of the current flag, is a round blue circle. The blue color is for peace. Imposed on the blue circle is a golden star symbol for diversity and unity. Emanating from the star are golden rays that symbolize prosperity. I hope Ethiopia can achieve what its flag communicates.

I also learned during my March 1993 visit that besides its ‘black gold’ coffee resource, Ethiopia also prides itself over its ‘white gold.’ The latter refers to its massive water resources, including Lake Tana which is the source of the Blue Nile. It is estimated that Ethiopia’s rivers provide about 80 percent of the water in the Nile. It is noteworthy that Ethiopia has been trying for years to build a dam across the Blue Nile before it enters Sudan on its way south to Egypt.

When this ‘Renaissance’ dam is completed and the lake behind is filled, it will provide more electricity than any dam in Africa. The Ethiopian government plans to make money by exporting electricity to neighboring countries. Of course, Egypt, which depends on the flow of the Nile, is much concerned about how this dam in Ethiopia will affect the flow of the Nile into Egypt.

My readings also informed me that most of Ethiopia’s people were among the poorest in the world despite recent double-digit economic growth for more than a decade. As noted earlier, I always thought that if an African country’s annual gross domestic product could grow by two percent or more above the national population growth rate for years, there would be enough economic growth to lift the poorest people in a society. Given the high annual population growth rate for most countries in Africa, it is a challenge to grow an economy on a per capita basis at a faster rate for the length of time needed to reduce poverty.

I have recently concluded that high economic growth is required consistently over many years before most of the poorest people realize any gain. This can be especially the case if there is high inflation and balance of payments problems. High inflation alone in the prices of essential items can move millions of people below the poverty line. In this regard, Ethiopia’s performance has not been desirable, and it recently had to obtain a large amount of U.S. dollars from the United Arab Emirates because its banking system was almost depleted of its foreign exchange reserves.

There are a couple of other negative factors that prevail in Ethiopian society despite efforts to the contrary. In this regard, it is not much different than some other African countries, but its large population translates into more cases. The factors include female genital mutilation (FGM) and obstetrical fistula. The ancient FGM practice is now illegal and the number of cases is declining, but millions of female children are still forced to undergo this risky surgical procedure to remove all or part of the clitoris. This traditional practice is considered a violation of women’s rights and a health hazard.

Obstetrical fistula frequently occurs when the woman is too young to conceive. This situation often results because of the practice of child marriage when young girls are forced into marriage when they are fully mature. In rural Ethiopia, it is not uncommon for a girl to be abducted for marriage and have her first baby before the age of 15. The life of the mother and baby are put at high risk when fistula occurs, leaving the mother with perforated interior organs that prevent her from controlling her bladder.

The medical and social consequences caused by fistula for thousands of women are too ugly to describe. Women who suffer from fistula are often rejected by their husbands and shunned by their communities. Ethiopia and northern Nigeria have more fistula cases than any of the other countries in Africa. A special hospital in Addis Ababa is devoted to the surgical repair and care of girls and women who have suffered from fistula.

I visited Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s mountainous, bustling capital city of nearly four million people, again in 2004, 2007, 2011 and 2018. I was amazed each time at how much the city had grown. It is never warm or dry enough for me in Addis, which like most major cities in Ethiopia is nestled in the highlands. The average high temperature in Addis is around 60 F. Addis is located at an altitude of 7,900 feet, making it the highest capital city in Africa. The Ethiopian highlands stretch across the country and are the longest range of mountains in Africa. Ethiopia is sometimes called the “Rooftop of Africa.” I learned this is a country where you need high altitude balls to play tennis.

The highlands have fertile soil and ample rainfall, permitting in the past three harvests per year. The high fertility of the soil in the highlands is one reason that this region of Ethiopia is densely populated today, and farm size is consequently small. The Ethiopian government has attempted to decongest the highlands by forcefully resettling people to the lowlands, but these kinds of mass resettlement programs have not worked well. In the meantime, Ethiopia continues to lose valuable topsoil. One friend of mine was fond of saying that Ethiopia could not advance unless it would be able to increase the amount of its topsoil. I have always been stumped by what he said, but I do know it is difficult to build a higher standard of living in an agrarian country on the widespread decline in soil fertility.

While most mountainous Ethiopia enjoys spring-like weather, it does also have some of the hottest places in the world. Its Danakil Depression in the far eastern part of the country, near Eritrea in Ethiopia’s Afar Region, is reputed to have the highest year-around average temperature in the world. It is also one of the lowest places on Earth. It is where the northern end of the great East African Rift Valley is located. It has volcanoes and the underground clash of tectonic plates makes it one of the geologic wonders of the world.

I last visited Addis in July 2018 with my Ethiopian wife and 20-year old daughter. I did not get out of Addis, but I was able to devote time to visiting ancient churches and several museums. I was happy to see in one of the museums a replica of the remains of one of the oldest (over three million years old) hominids, baptized ‘Lucy,’ ever discovered. Lucy was found by an American paleoanthropologist, Donald Johnson, in 1974 in the Awash Valley in Eastern Ethiopia, near Djibouti and the Danakil Depression. I was also able to see many artifacts from Ethiopia’s imperial periods, as well as gain much information about many of Ethiopia’s ethnic groups spread over a country with a geographic size about twice that of the U.S. State of Texas.

I was amused when my wife and daughter were called ‘diaspora’ by their friends and Ethiopian family members. The use of this word in reference to them reminded me there were millions of Ethiopians living abroad and this sizeable ‘diaspora’ population remitted millions of U.S. dollars each year to their families in Ethiopia. It is estimated that the total annual amount of remittances sent to Ethiopia is greater than the money generated for the national government by exports and donor assistance funding.

Harnessing the financial power of these remittances and the ‘diaspora’ experiences could present a new avenue for aiding Ethiopia and other African countries which also have many of their people residing abroad. The ‘diaspora’ provides more than money. They also often provide their countries with the expertise needed for faster development. Many members of the ‘diaspora’ return home and invest in their homeland and start businesses they learned to operate while abroad. Also, many Africans attend schools of higher learning in Europe and the U.S. and come home to apply what they learned. Perhaps one of the best actions which donor agencies can do is to sponsor the studies of Africans to attend universities abroad.

In 2004, I had just landed in Addis Ababa and was waiting for the shuttle to take me from the airport to the Hilton Hotel. Waiting next to me was a young Ethiopian woman from Washington, DC. It was clear she was a member of Ethiopia’s large U.S. diaspora group. She asked me what I was doing in Ethiopia I responded that I worked for a humanitarian assistance agency. My gentle response obviously struck an argumentative nerve in her and she unloaded on me a nasty heap of heated criticism in the most impolite manner.

She told me in no uncertain terms that Ethiopia did not need any external aid; therefore, I should leave Ethiopia as soon as possible. She loudly condemned all aid and people like me who worked for the agencies which provide aid. I tried to defend aid, but she would not listen to me. She firmly believed that no aid was the best aid, and Ethiopia is capable of progressing without using external assistance. She vehemently added that the U.S. should keep its aid money to help its own poor people. She continued haranguing me until we arrived at the hotel. I was relieved to be able to escape at the hotel from her scathing critique of aid.

Although this personal clash with one of Ethiopia’s own occurred many years ago, I still reflect on her harsh tone and cutting words, especially the phrase, “no aid is the best.” In recent years, I have begun to think that she may have been more right than wrong. Certainly, aid creates a dependency on the part of the host country and introduces recurrent costs which the country can ill afford. Maybe it is partly, for this reason, that little if any, trace of the impact of most of the billions of U.S. dollars of aid given to Africa over the last half-century can be detected today.

During this last visit to Addis, I was asked by a friend who had taught high school in Addis in the 1960s as a PCV to take photos of his old school. I hired a taxi and we finally found his old school had grown substantially over the years and it had evolved into a college. I was surprised to find tall skyscrapers next to the school, casting long shadows over what was once a small education institution. I was told that these tall buildings were built by the Chinese.

This statement reminded me that China was heavily involved with many projects in Ethiopia and had lent huge sums of money to the government of Ethiopia. Included in these projects is a critical rail line to Djibouti Port, giving Ethiopia a much-needed outlet to the seacoast. Ethiopia is the largest landlocked country in Africa. Also, the Chinese built and funded an inner-city electric light-rail service in Addis, which is the only overhead rapid urban train in Sub-Saharan Africa. I also understand that many Ethiopians have been given scholarships to study in China. I read recently that more Africans are studying in China than any other country in the world. The high number of China-educated Africans will impact on Africa’s future.

The growth in the number of people in Ethiopia always impresses me. I am always struck in Ethiopia and elsewhere in Africa by the youthful structure of the population. In this regard, some comparisons with the U.S. may be useful. The median age in Ethiopia is around 19 years, whereas, in the U.S., it is nearly 38 years. In Ethiopia, about 21 percent of the population is urbanized, while in the U.S. about 84 percent of the population is urbanized. This statistic on urbanization leads me to believe that Ethiopia has one of the most rural-based populations in Africa.

When I first went to Ethiopia in 1983, it had an estimated national population of nearly 38 million people. In 2018, about 35 years later, its population is over 108 million, making it the second-most populous country after Nigeria in Sub-Saharan Africa. (Compared to the U.S. State of Texas’ population of about 22 million.) This fast population growth rate and the youthful structure of the population of Ethiopia and other countries in Africa is indeed worrisome. I always ask myself how Africa will feed, clothe, shelter, educate, care for and employ so many people. And, the ‘youth bulge’ of Africa’s population is of great concern. Africa does not need more poor and unemployed people, but current projections point to a situation where the world’s poverty will be mainly concentrated in Africa in the future.

During my last visit to Ethiopia in 2018, I made a list of all the places I wanted to see in Ethiopia if I ever had the opportunity to do so. On this list is the Sol Omar Caves which is the largest cave system in Africa. This is one of many places in Ethiopia designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. UNESCO reports that it has designated more World Heritage Sites in Ethiopia than any other country in Sub-Saharan Africa. My dream is to be able one day to visit all these sites and see all the natural beauty and diversity that Ethiopia has to offer.

The rest of Mark’s life.

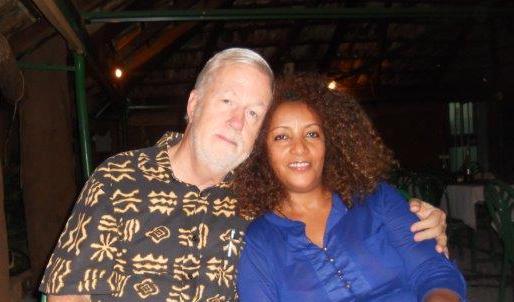

I met my Ethiopian wife, Almaz (Amharic for small diamond), in passing in the lobby of the Hilton Hotel in Addis Ababa on May 11, 2011. I was asking around who could help me find some traditional white handspun Ethiopian cotton cloth (called shemma in Amharic). This cloth is used to make clothes that most women wear in Ethiopia. She was working for a shop in the Hilton Hotel lobby and was on a break. When I first saw her, I was drinking Ethiopian coffee at a traditional coffee spot in the Hilton lobby.

She offered to take me to a cloth shop and, as it was lunchtime, she also took me to eat a traditional Ethiopian meal of injera and wat.

Mark’s career in humanitarian service.

Mark Wentling was a PCV (1967-71) in Honduras and Togo. Following stints as Peace Corps Director in Gabon and Niger, he began working for USAID in Niger in 1977 and worked as a USAID officer in Guinea, Togo/Benin, Angola, Somalia, and Tanzania. He retired from USAID on September 30, 1996, but was hired the next day by USAID on a Personal Services Contract (PSC) as an advisor for the Great Lakes.

After a year in this position, he moved on to work with USAID Missions in Zambia, Malawi, Guinea, and Senegal before beginning work with Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), CARE and World Vision, in Niger and in Mozambique. In his last position with World Vision, he covered all of Africa from his base in Maputo and worked in a number of African countries.

In 2006, he returned as a PSC to work for USAID in Niamey, Niger. Following three years in this position, he moved to Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. In early 2011, he worked for six months with USAID’s Regional Mission for Southern Africa based in Pretoria.

In July 2011, he accepted a position as Country Director for Plan International in Burkina Faso. He remained in this position until June 2015, when he moved with his family to Lubbock, Texas.

In October 2016, he worked on a six-month contract with USAID’s West Africa Regional Mission in Accra, Ghana. In 2017, he held a similar position with USAID/Mali, and in 2018 he was USAID’s Resident Advisor for the President’s Malaria Initiative in Angola. In 2019, he worked for USAID’s regional office in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

He has also published five books, including his African Trilogy. In addition to these five books, he has published a dozen professional articles.

He makes his U.S. home in Lubbock with Almaz and two of their seven children.

I can’t wait to read it. How do we buy the book? Thanks.

Unfortunately, it is highly doubtful this insightful book will ever be published because of the length of the book manuscript, 885 pages (294.314 words). I continue to query academic presses and other publishers, but I do not think this book will ever be published. If any of my FB friends have any ideas about how I can get this long book published, please let me know.

Break it into its components or use topics as titles to different books 2 to 4 books.

I have been following your writeups since 2000. Looking forward to the insights in the new books.

Your right! Cut it in half and self-publish two volumes. If you use print-on-demand, you buy just enough copies for your buddies.

Thanks for the suggestion. I was actually thinking of three volumes divided into various regions of Africa. For example, I was thinking of a volume on West Africa, but that would be about half the book. The Niger and Togo chapters represent 20% of the total memoir. The length of a chapter varies according to how much time I spent in a given African country. If no academic presses accept to print my memoir, I will definitely try to self-publish.

That will also work! If you haven’t already, once divided up, run the first section (volume 1) by an editor or two. For the cover design, seek out an artist. Even if you wish to use an old photos (for the 3 volumes), the artist will have great ideas about how to crop and colors, etc. The books should generally have the same design. KDP Publishing (formerly Create Space) does not charge per se. Check them out.

Thanks, Lawrence. I am going to give myself all of 2020 to try to get this long book published in its entirety or in parts.

Hi Mark

Having played a part in your career in Africa, I am especially interested in reading this magnum opus, whether in 2 or 3 volumes.

Thanks, Martin. Your name and role in interesting me in Africa is duly mentioned in my memoire.

What a coincidence that out of 54 countries, the one excerpt chosen at “random” was…ETHIOPIA!! Hmmmm….Coyne has gotten more shameless over time…what about swapping out the chapters on Niger or Mali…? Good luck w/ publishing.