“Somali Moon” by Jeanne D’Haem (Somalia)

Jeanne D’Haem will be one of the five published writers to lead panel discussions at the September RPCV Writing Workshop in Maryland. Read her Peace Corps essay below. — John Coyne

•

Somali Moon

By Jeanne D’Haem (Somalia 1968-70)

Emeritus professor, lecturer, memorist, essayist

There was a night, fifty years ago, when people all over the world watched the sky. They were not concerned with yet another tragedy of war or weather. No one had blown up the world trade center or machine gunned hundreds of people at a park. On one special night in August 1969, they were watching the moon with wonder.

Any baby boomer you know can tell you exactly what they were doing on August 20, 1969. Most will report they were watching the TV. Riveted by a black and white, 15 inch screen. There was plenty of parking in New York City and Grand Rapids; everyone was inside watching Neil Armstrong. A friend described camping in Yellowstone with a generator. A woman in Sarasota reported that she had been unable to contact her husband in Mexico despite satellite communication appointments. She was furious when the TV showed Neil Armstrong’s wife talking to him in space but she could not talk to her husband.

My sister was an aerospace engineer. She watched at NASA where they feared the astronauts could bring back a virus that could wipe out humanity, even though scientists believed that the chances of finding anything living on the moon was one in a hundred billion. NASA had built a Lunar Receiving Laboratory where airtight boxes of moon samples would be put into a vacuum chamber where lunar gases could be analyzed. There would be no welcome home hugs for the astronauts.

The world’s people, rich and poor, in Nome and in Nairobi watched and wondered. For this shining moment, in a long history of tears and trouble, mankind was uplifted and united in amazement. Like a powerful lodestone, the distant moon tugged at the earth’s people, like she does with the ocean tides.

I say this with some authority since I was living in Somalia at the time and travelled around the world a few months later. I remember a traveler in New Delhi who complained loudly that the Americans could get to the moon on time, but his flight to Agra was delayed.

On the night of the actual lunar landing, the moon over Somalia was full and rose bright saffron yellow over the little village where I was a teacher. Everyone watched for the American rocket. I had taught my students that the rocket would be too small and far away to see, but I too, sat outside my house and looked for it. Like everyone else, I was disappointed. There was nothing to see but stars and satellites.

I knew that my friends back home in Ann Arbor were watching, as were people in Moscow, Hang Chow, Cusco, and Kathmandu. It felt as though the world had stopped to hold its breath, and was for once in its entire history, united with a single sense of wonder. Together, the world’s people marveled at the face of the moon and the courage of men and women. The moon has always impacted the imagination of men. Our calendar and Sabbath come from the Babylonians who observed that the full moon is not expanding or contracting but resting. They copied the idea of a time of rest, leading to our Sabbath but the phases of the moon have lost their importance in our modern life. I felt very peaceful in the stillness of the sleeping desert that night, even though I knew that for many Somalis this moon trip was an outrage. Another injustice perpetrated by the United States without concern for anyone else.

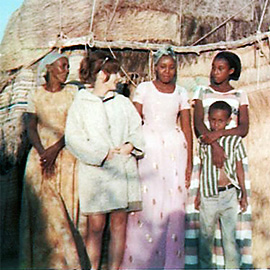

Jeanne in Somalia

“We will learn about the solar system.” I told my students that June. I taught English, math, science and gym, in a small secondary school with one other teacher. Most of my students had been awakened by the Mullah’s call to the early morning prayers. “E la he la he ela Allah, There is no God but Allah.” They had taken the family livestock to the wells for water. Many had climbed into the well and thrown water up to the top in a carved wooden gourd or a water basket. Some had never seen electric lights, ice, or aerosol. I wondered how these earnest young people could possibly understand jet propulsion. Their sweet, serene faces gazed back at me as I spoke about rockets and astronauts. The soft Arabic features on mahogany skin were perfectly proportioned. I had never seen such uniformly beautiful people, or such bored students.

“The Americans have built a rocket and are sending it to the moon.” No response. “It will have to have three parts because the moon is so far away.” Vague disbelief, not about the rocket but the distance to the moon. “The first part will fall off when all of the petrol has been used to get away from the earth. Then the astronauts in the command ship, Apollo 11, will link up with a moon landing ship in space, and go 25,000 more miles to the moon. They will go around the moon several times.” Every week I received teaching materials from NASA, the only science materials that were available in the school. It was exciting to have some good materials, but I couldn’t tell if my class didn’t understand the English words, what I was talking about, or both.

“It is a long way to the moon.” I tried making the idea easier in a bid for comprehension. Blank faces gazed up at me. I only had 20 chairs for the 40 students in my class, so the boys sat two in each chair. Sounds of the wooden bells on the camels at the wells wafted gently through the room. It gave me a nice dose of reality.

I had expected more of a reaction to the news of a rocket going to the moon, but the class had an “and then what” attitude. They had observed many incomprehensible pieces of technology. Trucks had rolled across the desert before many people in the nomadic clans had seen a key open a lock. They had not been part of the gradual development of technology in the rest of the world, now sophisticated products dropped into their midst.

The Somalis were quite used to seeing satellites. They knew they were sent into the sky by the Russians and the Americans. The stars, the Milky Way and the planets that are visible in night sky in a place without electricity was a glorious shock to me when I came to Somalia. The beauty of our galaxy is hidden from almost everyone in the developed world. My students were casually accepting of satellites and a rocket going to the moon until I explained, “The rocket will land on the moon’s surface and the astronauts will get out and walk on the moon.” This last statement caused a whisper of surprise. At last my students were intrigued I thought, little suspecting what the excited whispers were all about, and the trouble that lay ahead.

That night, two of my students, Mohammed Attah and Ali Abdi, came to my house on the outskirts of town. When the moon was full it illuminated the rocky paths and everyone went out to visit their friends. When the moon was new, everyone stayed home and slept early. That night the moon was divided precisely in half as if it had been dipped in chocolate.

“Come in boys, come in boys,” I gestured, holding open the thin wooden door with only a bolt to hold it shut.

Tall and lanky, the boys had easily walked through the town unperturbed by the wild dogs or hyenas that roamed the streets after dark. Now they crouched behind one another in the doorway, frightened by my cat. “She won’t hurt you, it’s just my kitty,” I said, taking her up into my arms. However, neither boy would enter the house as long as she was in the room, and I banished her to the courtyard. They wore the white shirts and khaki shorts that were the uniform of the schoolboy. Mohammed was so tall and angular that his long legs looked like tent poles. He had an endearing face and a sad droop to his eyes. I always wanted to hug him. Ali Abdi was one of the most intelligent young boys I had ever met. He spoke Somali, Arabic, French, and English.

“Miss Jeanne,” began Ali Abdi, “my family is very upset about the rocket.”

“What is it about the rocket that is a problem, Ali?” I asked.

“My uncle is afraid the rocket will kill all the Somalis.”

“Ali, it won’t go near Somalia. Why would the Americans want to kill the Somalis?”

“But, Miss Jeanne,” he continued, “it says in the Qur’an that there is a tree on the moon. When a Somali is born, a new leaf grows on the tree. When your leaf falls from the tree, you will die.”

“If the Americans land on the moon, the rocket may come down on the tree, or disturb it in some way and all the Somalis will die before it is their time,” added Mohammed.

“Boys,” I reassured them, “there is no air or water on the moon. A tree can’t grow on the moon. Tomorrow in school I will show you some pictures of the moon’s surface. It shows that the moon is actually a desert where nothing can survive.” I talked very slowly, seeing the distrust in their eyes that did not abate. They were not convinced and I realized in the silence that followed, that the Somalis had survived for centuries on a desert and there were trees there as well. Actually the pictures of the moon did look a little bit like the area surrounding our little town. When you get to know the desert, it is full of color and design, but you must learn to look closely. A casual glance by those not familiar with its secrets does not reveal what is hidden by the glare of the sun.

Ali Abdi and Mohammed stared at me. They were trying to translate my English into Somali words and then into what they knew of the world outside my door. Despite our conversation, I could tell that they were still skeptical when they left. The boys followed the rocky path from my house back into the village, a short distance away. Their two shapes cast long shadows, but the moon did not follow them. She waited right above my head. The light of the moon, a borrowed light, gave an illusory appearance to everything. The boys knew every rock in the village, they were not easily frightened by anything native to Somalia. They were however, disturbed by news that called into question some ancient traditions.

Over the following weeks I gave up trying to discredit the notion of a tree on the moon. I was calling into question the very Quran and risked insulting my student’s religion. I stopped bringing up this strange notion of scientific proof and the inability of trees to grow on the moon. In my own country, most people accepted the virgin birth of Jesus, despite its scientific improbability. We didn’t discuss this issue in science classes stateside, and I decided it would be the better part of valor not to dispute the Somali notion of “The Tree of Life.” The Somalis revere Jesus, the son of Mary, as a prophet, not a God. They question the reality of his virgin birth and resurrection from the dead. The “shahada,” “There is no God, but God,” is recited every time Muslims gather to pray and is the profession of faith upon which the pillars of Islam are based. My students had a hard time understanding how Christians profess to worship one God, yet believe in a Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. They would often ask why I had three Gods, but pretended to worship one.

I did attempt to reassure my classes that the rocket would not come near the alleged tree. “The rocket is small and the moon is big,” I said. “It will not land on the tree.” However, I could see that half the boys had seen the aircraft that flew into Somalia, and obviously everyone watched the moon and knew what size that was. In the eyes of my students, long disciplined to be acutely aware of their surroundings, the rocket seemed awfully big compared to the moon. My assurances that the rocket would miss the moon tree were not very logical or reassuring.

The American Consulate would get films about the moon shot and even actual pictures of the landing to my school. They would send a Land Rover with a movie projector and generator out to the village. We could show the movies of the moon walk on the whitewashed wall in the school yard. It was probable that this would happen the night after the lunar landing. I was stunned. Letters often took a month or more from home, but I would get a movie from the moon the very next day. Even I was very excited about the technology involved in this operation.

The night of the moon landing, everyone waited and watched in the little village of Arabsiyo until we gave up and went to bed.

The following night featured the sunset, then a gallery of stars. This was followed by the main attraction, the full golden moon gracefully rising over the desert. It called the entire population of Arabsiyo to the school yard. As promised, a Land Rover fitted with a gas generator had arrived with, not one, but two, films of the moon shot. One was actual footage of Neil Armstrong stepping down onto the moon. The other was an animated documentary explaining the three stage rocket, technical assistance teams, weightlessness in space, and space suits. It had pictures of a simulated moon walk in a studio. I decided to show the actual footage of the moon walk first. Later I wondered if that was my mistake.

An enthusiastic crowd of about 100 people had already gathered when I arrived with the consulate driver, Ali Esa, and the Land Rover. Mohammed Attah and Ali Abdi pushed their way through the crowd and greeted me. “Everyone is very excited,” they told me. “One of the sheiks is here to see this moon movie.”

Ali Esa backed the Land Rover into the courtyard after Ali Abdi chased the little kids, to get them out of the way so we could get the car into position. Even more people had arrived and it was difficult to maneuver the jeep. Ali Esa was hesitant to bring the car into the school courtyard. “Some of these people are angry,” he said.

“After they see the movie, and that the rocket did not come anywhere near the Somali tree, they will understand,” I assured him.

As we set up the movie projector, people sat on the ground in the courtyard. I saw many of my students and waved cheerfully at them. They did not wave back, but waited nervously in little groups. Only Mohammed and Ali Abdi stood with us on the open back of the Land Rover. I thought the crowd was impatient and expected things to settle down and the mood to soften when the movie finally started to roll. The film was actual footage of the moon walk, and it had been broadcast on television sets all over the world. The picture was grainy and flickered as you would expect from something broadcast back to Earth from the moon.

It was not well received by the fitful crowd. Several rocks were thrown at the screen and persistent undertones grew louder and louder. People began to shout and I turned to Mohammed for a translation. I could not understand the rapid Somali or the growing animosity of the crowd. “The people are saying that this movie is a fake,” Mohammed told me. “They say the Americans are trying to trick the Somalis into believing they went to the moon. “Miss Jeanne,” he questioned me directly, “nobody saw any rockets last night. If we can see the satellites why didn’t anybody see the rockets?”

Well, I knew the picture was grainy and flickered in black and white. The picture wasn’t good visually and they thought it was a fake. It was a short film however, and we quickly put on the next tape of the documentary.

This film was in color and the photographs were clear. The crowd settled down to watch. I was relieved. I didn’t want the families of my students to go home convinced that I was teaching lies in school. They sacrificed the labor of the boys to send them to school. They could easily pull all my pupils and take them back to tend the camel herds in the interior.

Attentive silence filled the courtyard. Some of my students could follow the dialogue and were translating for their families. The three stage propulsion rocket was demonstrated with a little model. The command centers were shown, and space suits were demonstrated. Shots of the weightless astronauts floating around the cabin drew gasps from the audience. At last I thought, they believe it! Unfortunately it was true, the villagers had begun to believe that the American rocket had landed on the surface of the moon.

The mood tensed and gradually escalated into hostility when the simulation of the moon walk began. The exterior of the rocket showed on the corner of the screen and the camera panned the set of the lunar moonscape. A rock hit the wall of the school acting as our movie screen. When the door of the rocket slid open, more rocks were thrown. When the actor in the space suit ventured down the ladder to step onto the ancient dust covering the moon, the school yard erupted. Suddenly the screen was pelted with rocks, then many people turned to the Land Rover. Angry men climbed on the wheels of the jeep to scream in my face.

“American!”

“New York!”

“Kennedy.” These were the only English words most people knew. I was stunned for a moment. I couldn’t wrap my mind around what was happening. Foolishly I tried to explain.

A rock hit me in the back, and another followed. Rocks hit Mohammed and Ali Abdi who were in front of me. Women were screaming, babies were crying, children began to run around in the confusion. Rocks continued to hit the projector, Ali Abdi, Mohammed and me.

“Get inside quickly, sir,” said Ali Abdi, pushing and pulling me toward the front of the jeep. He was quite frightened, and that alarmed me more than the shouting. He forced the door of the cab open by hitting several women in front of it with a stick, and I climbed in. Ali Esa was already in the driver’s seat and he locked the door seconds before hands grabbed the handle.

“Let’s get out of here,” he said. “These people are nuts.” He started the jeep and we just left the projector still rolling in the back. He turned on the car lights and honked the horn surprising everyone. Mohammed and Ali Abdi jumped into the back with the movie projector and turned it over so it would not fall out.

Get down” called Ali Esa, as a rock bounced off the rear window and it shattered into a thousand pieces, all over the boys in the back. I was crying on the floor and shaking because I was so mad and so confused. What was the matter with these people? I felt the truck lurch ahead and stop short over and over. Miraculously no one was injured that I know of, and we made our way out of the courtyard and through the empty streets of the town.

Ali Esa decided he had had quite enough of Arabsiyo and dropped me off at home with Mohammed and Ali Abdi. He went back to Hargesia and the safety of the American Consulate garage that night, using the bright light of the still dispassionate moon to guide him on the darkened track which leads through the desert.

I bolted my door firmly against this bizarre night. I lit my oil lamps, one after the other against the darkness of this frightening evening. The lamps have a soft light which is comforting when things are quiet, but at the time I really wanted a searing searchlight to see what was going on. Fortunately I suppose, I didn’t have a giant light to draw any more attention to myself or the twentieth century than I already had.

Ali Abdi and Mohammed were philosophical. “The people think you were insulting them with the first movie,” said Mohammed, and Ali Abdi agreed. “They thought it was a fake made up by the Americans to fool the Somalis. You could tell it was just a fake by the way it looked.”

“Then, when they saw the second movie, the people became very upset. That movie was real and then everyone believed in the moon walk. The people don’t feel that the Americans had a right to go to the moon,” explained Ali Abdi carefully. “It is the sacred place of the holy tree to the Somalis. Why do the Americans think they can just go and take over the moon?”

Mohammed added, “Everyone was shouting that the moon belongs to the Somalis.”

“Besides that,” continued Ali Abdi, “everyone was frightened about the tree. They couldn’t see it when the picture showed the moon. My uncle thought maybe the rocket landed on the tree.”

“Nobody has died so most people think the rocket missed the Somali tree,” said Mohammed.

“Will you get in trouble with your families for being with me tonight?” I asked.

“I am always in trouble about the school, about English, about Americans,” replied Mohammed with a little laugh. I think that he enjoyed harassing his elders, like most adolescents.

“Do you think there will be trouble in town or at school about this?” I asked.

“Everyone will talk and talk about this for weeks,” said Mohammed. “Everybody in town will have a different opinion.”

“Most people are glad that you brought the movies,” said Ali Abdi. “They don’t hate you for telling us what is happening in the rest of the world.”

“I think a lot of these people are stupid,” said Mohammed, his head in his hands. “The Americans are going to the moon and the Somali people don’t even know how to make a needle.”

Ali Abdi, however, was defiant about the incident and I loved him for his pride and the lesson he taught me. “We have a Somali proverb,” he said, sitting with beautiful posture as always, erect with quiet grace and dignity. “The last camel in line walks as quickly as the first.” The last country in the world is affected by the leading nations. This is one planet, what happens to the least of us, happens to the rest of us. And so it happened that fifty years later, most Somalis, a nomadic people, are complaining about their cell phone bills. They hold in their hands more technology than when man first walked on the moon.

•

Jeanne D’Haem (Somalia 1968-70) is an emeritus professor at William Paterson University and frequently lectures on issues in special education. She has published two prize-winning books and numerous journal articles. The Last Camel won the Paul Cowan prize for non-fiction. Desert Dawn, with Waris Dirie, has been translated into over twenty languages and was on the bestseller list in Germany for over a year. It was awarded the Corine prize for non-fiction. Her most recent book is Inclusion: The Dream and the Reality inside Special Education.

Bravo, Jeanne! I too served in Somala, in the south, and I recall one iman in particular who kept shouting that all Americans were infidels, for we claimed the world was round when the Koran knew it was flat!

I left a few months before the moon landing, and yes, I do recall the day well, at my cousin’s house, all dozen or so of us snuggled tight so we could get our scrunched noses to the screen. I don’t know what Baidoans may have thought of the moon landing. The science we taught in the middle school was more biologically focused.

On the one hand, I wish we could have left them blissfully ignorant. They seemed happier then. On the other hand, they wanted to march into the modern world, and we tried so hard to help them.

I am so sorry that you got attacked, and am thankful that you survived to tell us your splendid stories.

Jeanne,

I enjoyed immensely this well-crafted account of your first-hand experience in Somalia when the American moon-landing occurred in 1969. I enjoyed reading about how Somalia was many years before I endured the war-torn Somalia in 1993-94. I had heard many good things about the pre-war Somalia from my colleague, John Marks, who had been a PCV in Mogadishu in the 1960s. The Somalia he knew during his PCV years was very different than the Somalia we knew almost 25 years later. I hope he has a chance to read your book.

By the way, like everyone, I remember where I was when the Americans landed on the moon on July 20, 1969 (not August). I had finished my first stint as a PCV in Honduras and was traveling on a shoestring in Europe with two PCV buddies who served with me in Honduras. We were in a bar in Florence, Italy watching the big event with a crowd of Italians on a small-scree TV. After Armstrong stepped onto the moon’s surface and the crows learned we were Americans, we were cheered and offered free drinks. Thus, our July 20, 2019 experience was very different than yours.

Lovely work, Jeanne!

It really captures the passion Somalis have about their understanding of the world and how different that can appear to us Westerners.

I also recall where I was in that historic evening – on the Bajun Islands south of Kismayo. My term as a PCV in Somalia (1966-69) had ended and before leaving to explore East Africa and beyond, I had wanted to see the far south of the country. A Somali friend and I sat on the tiny island and speculated about what the moon must be like. In some small way I felt about as far from the rest of the world as our space heroes that night.

In 1967 I spent a week in Arabsiyo while working on a WHO sponsored TB survey of the North. It was one of my favorites.

Your story also reminded me of the central role that the moon has in Somalia, not only to mark the passing of time but frequently the only source of light on dark nights.

Thank you!

Marvelous story! Well told. There is no doubt that the moon landing was a pivotal event in exposing cultural differences, perceptions and world views. Topic for an anthology!

I was also in Somalia at that same time, 100s of miles away from Jeanne’s location. I recall riding from my village to the regional capital in the back of an empty trade truck with about 20 nomads, all of us standing and holding on to the lattice of overhead pipes that would support the tarpaulin cover of a loaded truck.

It was the middle of the night with clear skies and a nearly full moon almost directly overhead. I had been watching the moon all trip and had been reflecting on my amazement of the accomplishment of sending a man to the moon. At last, with much pride, I told my nearest companions in their Somali language: “Some of my brothers are flying to the moon now and will be walking on it tomorrow night!” “Which moon?” they replied. “That moon!” I responded while pointing to the only moon visible. They immediately cracked up. It was the most outrageous thing they had ever heard. As word spread to the other passengers, so did the laughter until the whole back of the truck was filled with guffaws, pointing at the moon and people bending over in pain with their belly laughter. What amazed them was my ingenuity in making up such a story that was so obviously untrue. I was immediately nicknamed “nin wallin” (the crazy man) and so greeted afterwards back in my village when seen by any of my fellow passengers.

Thank you for your memories, nin wallin. A great nick name! I hoped that others would share their experiences, wherever they were of that hopeful event. So pleased to read yours.

At that I was a student at not far away from Arabsio. I was in Gabiley intermediate boarding school. The morning after the news crack of Apollo landing on the moon, ee had English as the first period.Our teacher (PCV), Mr Coach, entered the class (7B). His face was radiance. He was more excited than ever, a state he was never in before. Immediately after exchanging the usual ritual of “Good morining students ” and our reply “Good morning teacher” Mr Coach took the linestone chalk on the edge of the blackboard and wrote “Today the three American astonauts landed on the moon safely” then faced us without uttering another word told ys to repeat after him over and over and and again and again. When he stopped I was yawning, would you believe. In our small I read material about space, not about shuttles and soace explorations giing on at the time. I was bemused a bit. Then got tired. In fact, i immediately believed and became excited too but lost the momentum by the morning repetition of the sentence. I hushed to my friend next to me abdirahman “what is the point of repeating. We are barrots. There is nothing new about the English to learn from. We are wasting time. I have got questions about the event itself. How did it happen. And so on and so forth”.

As I knew later in my life, he was doing that because of the sweetness and impirtance ti be a nationalist.

I wasn’t born then, but my dad who was a principal of a school Americans taught, Odweyne, told me about how American teachers had nothing else to teach to the students for the week that followed the event. I also remember that’ in my elementary school years, my geography teacher could not convince me that the earth was round and its relationship with the moon. My dad, may Allah bless his soul, explained to me by creating a solar system model in our backyard. It was easier for me to believe my father. I can’t imagine if someone else had to convince me.