Seventh (and last) Peace Corps Fund Award: “Taxi” by Sue Rosenfeld (Senegal)

Sue Rosenfeld (Senegal 1977-81) joined the Peace Corps in 1977 and 40 years later she still lives in Africa. She served as a Junior High School English teacher and then as the PCVL for TEFL and as a teacher-trainer at the Teacher Training Faculty of the national university. Originally from New Jersey, Sue obtained her BA in Latin from Dickinson College and her Masters in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages from Teachers College, Columbia University. After serving four years as a PCV in Senegal, Sue taught for three years on a Fulbright grant in Burundi. She next moved to Niger where she has lived ever since. Initially, she directed the English Language Program at the American Cultural Center and then for 24 years–its entire duration–directed Boston University’s International Study Abroad Program in Niger. Now partially retired, she is an adjunct at Niger’s national teacher-training faculty. Today, she trains future Junior High School English teachers. Sue lives with her two dogs, Nola and Jazz, and helps care for Bebe and Lamisi, the two chimpanzees at the National Museum.

Taxi

By Sue Rosenfeld

Taxi cab drivers are a much-maligned group in Dakar, but I’ve usually had pretty good luck with them. I’ve probably taken a taxi in Dakar on more than 500 different occasions, and I can only recall two or three ‘bad trips.’ There have been many, however, which were unexpectedly pleasant, personal, and funny. There was the time, for example, when I was going to the Peace Corps director’s house on a Saturday evening with two other single female volunteers. Our taxi cab driver wondered what three unescorted women were doing gallivanting around Dakar after dark.

“Tell him we’re married,” urged one of the others, “and that our husbands are home and this is our night off.”

“Eh…?” said the driver, when I translated that into Wolof. “Your husbands let you do that?!?”

“Tell him WE decide,” said the instigator of our merry little lie.

“But this cannot be,” replied the driver, even more incredulous now. “Yalla does not want it to be this way. Your husbands must have other wives and they are with THEM tonight.”

“No,” replied my friend, making her own way through Wolof syntax this time. “They each have only one wife but she (pointing to me) has two husbands – a rich one she doesn’t like and a poor one she loves.” (Thanks, pal)

To this unheard of remark, our driver responded by cutting across two lanes of traffic and swerving off the road. “If they do this in American, Yalla grant that I NEVER go to that country. It is not natural!” (This will cut down on visa applications, I thought)

The rest of the trip was made in silence: his shocked; ours amused. We arrived at our destination, recounted our little gag, and thought that was the end of it. In fact, we more or less forgot about it.

The following year I hopped into a taxi, greeted the driver with the standard ‘Assalaam Malaikum,” told him my destination and opened a notebook to do some work.

“Ah, Madame,” he began, “How are your husbands?”

“My husbands?”

“Yes; the poor one whom you love and the rich one you don’t.”

“Oh…it’s you! I don’t have two husbands. I don’t even have one husband. That was just a joke my friend told you.”

The guy was devastated. “But, Madame, I’ve told all my friends! My family! About how in America the women can have many husbands; just the opposite of here!”

Well, since then I‘ve been more careful about what lies I tell taxi cab drivers.

For me, a taxi ride is a perfect occasion to try out new words and expressions I’ve learned in Wolof. The driver will be a native speaker or at least someone who’s been speaking Wolof since childhood, and I’ll probably never see him again, in case I make a fool out of myself. Our contact is limited to that ride and as the ‘client’ I can terminate the conversation anytime I want. Yes; I’m probably indebted to taxi cab drivers more than to any one other group for the improvements which occurred in my Wolof after my ‘formal’ language training ended.

There is one taxi ride I had which stands out above all the others. I’ll probably never forget it. I was going from the school where I taught back to the Peace Corps office. No free taxis were in sight so I started walking. Finally, an old, decrepit, beat-up taxi pulled up beside me (taxi cab drivers in Dakar assume that ‘toubabs’ never prefer to walk when there’s the possibility of riding in a taxi) and stopped. I took one look at that beat up, run down machine and almost didn’t get in, wondering if I could make it to the office on foot, about two kilometers down the road. The driver, noticing my hesitation and understanding the cause of it, assured me, in broken French, that it was, indeed, a fine machine: “Taxi…bon…aller partout” (tax…good…go everywhere).

Then I took a look at the driver. He was the oldest-looking taxi cab driver I had ever seen. In fact, he was one of the oldest-looking Senegalese I had ever seen. “Well, Gramps,” I said in Wolof, “the taxi may be OK, but what about you? Are you a little old to be driving?”

“Yes,” he readily agreed. “It’s my son’s taxi and I’m taking his place today. Get in.”

One always obeys one’s elders in Senegal, so I got in. There were no springs in the seats so we were jolted about even on a fairly well-paved road. Grandpa appeared to be sitting on the floor. There was a seat cover, but only the back of an actual seat. The seat itself must have been a little footstool. There were no door handles nor was there a pane of glass every place there should have been. What upholstery there was badly ripped.

Gramps himself was quite a specimen. He was rather Gandhi-esque: shriveled, thin, almost transparent. He wore an old grand boubou of common cloth. Hanging around his neck on cords of leather and string were numerous gris-gris, which contained verses from the Koran. On his head was a beanie-type cap, common to men of his generation in Senegal. To top this off, despite the heat, a long black and white (alternating squares) wool scarf was wrapped several times around his neck.

He asked me when and where I learned to Wolof and I told him, “I work with the Americans,” assuming that one so old and ‘out of it’ would never have heard of the Peace Corps.

“Uh-huh,” he mused. “You must be with the Corps de la Paix.”

Surprised, I told him I was.

“Kennedy,” he said.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Kennedy,” he repeated.

At this point, by chance, we were down the road from the major girls’ lycée in Dakar. It is called Lycée Kennedy. That’s what I thought he was referring to.

“Yes, yes,” I muttered. “Lycée Kennedy is over there.”

“No,” he said. “Not the lycée. The man. Your president. John Fitzgerald Kennedy. He founded the Peace Corps twenty years ago.”

I was too flabbergasted to say anything so he continued.

“He wanted to help Africa. He wanted to help us. That’s why he founded the Peace Corps. But they killed him. In 1963. They didn’t understand. That was bad. But they left the Peace Corps. And you’re here. You want to help us too. That’s good.”

With that we arrived at my destination and, in a daze, I paid him and stumbled out of the car, thankful that, even against my better judgment, I had had the good fortune to in that broken down old taxi.

Delightful storytelling! Made my day! Write a book (if you have not yet done so) . . .

I have lots of vignettes. Maybe will be a book someday. Your comment made MY day so thank you very much. Sue

As the son of a DC taxi driver I found these tales particularly interesting. I would add only one comment, please understand that taxi drivers talk to clients for one reason, to get a better tip. And of course whatever they say it is to encourage the client to be more generous.

This guy was just talking sincerely. But it was a very moving experience for me and he got a good tip. Thanks for the comment. Sue

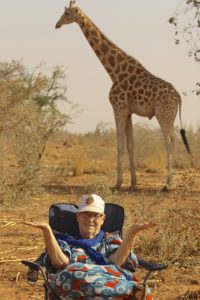

Sue, great piece! As someone who rode with you in at least a few Dakar taxis pushing 40 years ago, I especially enjoyed it. It is good to learn that you are still in Africa, in the shadow of giraffes, no less!

Anne Neelon! Poet par excellence! Send me you e-mail address

It’s aneelon@murraystate.edu .

So you are still meredebebe? (I don’t think I have French accents on my computer). Still in Africa? I’m still in FL. If you write me I promise I’ll write back (see still not dead)

How funny to read this here. As some people realized, I was quite miserable in Peace Corps. There was quite simply waaay to much for me to take in. I was unable to process all of what I saw.

I was, however, where I became a journalist.

I remember sitting in so many taxis traveling across such brutal country, looking at the starvation and the misery and — for the first time in my life — willingly putting together sentences in my mind in order to try to make order out of what was chaos.

I struggled deeply to come to terms with the poverty that existed there, and with the face of life that I had been born in a wealthy country. I never got to the point of accepting that anguished truth.

When I left, I vowed I would be back to write about what I had seen.

I did come back. My stories appeared on the front pages of American newspapers, back when newspapers substantively shaped public views.

Since then I have returned to Africa many times, always as a journalist. Now I am an author and my experiences in Senegal have found their way onto every page I publish. The experience of having confronted so much agony on so many faces throughout my entire time in Senegal has shaped my voice and given me a very different perspective from many American writers.

Although I was unhappy for the entire time I was there, I wouldn’t trade that experience for anything.