Uzbek Zero by Bea Hogan (Uzbekistan)

Uzbek Zero

by Bea Hogan (Uzbekistan 1992-94)

•

“Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, you feed him for a lifetime.” It’s Peace Corps gospel, which had served the agency well as it spread throughout the developing world. But what happens when a country doesn’t want your help, and you’re sent there anyway?

I found out, when the Peace Corps sent me to Uzbekistan in 1992. The Cold War had ended, and the Peace Corps was expanding into the former Communist countries of the Eastern Bloc. When the Soviet Union collapsed, in December 1991, James Baker, then secretary of state under George H.W. Bush, said he wanted to see 250 Peace Corps Volunteers on the ground within a year. Volunteers, he said, would provide “human capital” to help these countries transition to market economies, Baker said, and advance U.S. foreign policy goals in the region.

I’d been accepted to the Peace Corps, but had all but given up on the program when my initial assignment to West Africa was deferred due to political turmoil. A few months later, I was offered a spot in Uzbekistan, a country whose name I couldn’t spell and whose history I did not know. My placement officer filled me in: Uzbekistan is a country in Central Asia that from 1924 to 1991 was a part of the U.S.S.R. Though I’d preferred West Africa because I speak French, I was intrigued by the opportunity to witness history and learn about a part of the world I barely knew existed. I was 23 years old, an English major sputtering to launch, and the Peace Corps, I thought, would not only pad my resume, but give me a chance to travel and do something meaningful.

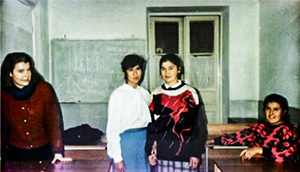

Bea Hogan with some of her students

In December 1992, I stepped off an Aeroflot plane with 53 other Americans in Uzbekistan, and began a journey that would change my life. The trip took three days, from DC to New York to Gander, Newfoundland to Dublin to Moscow (where we switched airports and spent a few icy hours in Red Square) and then finally to Tashkent, the capital city. An Uzbek woman in a multi-colored kaftan eventually showed up to greet us, and, as I listened to unintelligible words tumbling out of her mouth and watched the sun glinting off her gold teeth, I started giggling. My eyes were dry from all the flights and I blinked a few times to get my bearings.

“The Peace Corps is on its way to freedom’s new frontier,” Elaine Chao, then the director of the Peace Corps, had announced seven months earlier. She’d been referring not just to Uzbekistan, but to the entire vast territory of the former Soviet Union, from which 15 new countries had emerged. Advance teams from the Peace Corps had crisscrossed the region lining up host countries, Volunteer groups were assembled, and programs slapped together in record time. Ukraine was the first to sign a Peace Corps country agreement that year, followed by Russia, Armenia and finally Uzbekistan.

In the frenzy to get volunteers to their posts — to meet Baker’s quota — the Peace Corps had breached its own protocol. “Many of the steps necessary to introduce effective programs were rushed, done superficially, or not done at all,” a GAO report later determined. The information we were given was largely useless: a packing list for the tundra, a medical guide for the bush, and lessons on languages that were sometimes not the predominant ones at our sites (as was my situation: Samarkand was a Tajik town, and I studied Uzbek and Russian during training). Little thought had been given to how, exactly, we were going to proceed as Volunteers. Once at site, we had to create our own jobs, find our own lodging, and rely on locals to feed us when we ran out of money.

The president of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov, was a Soviet-era apparatchik who could not have been too keen about the idea of Americans roaming around his country — he was busy quashing dissent and consolidating power — but ultimately accepted Volunteers to avoid being “put on the shit list for U.S. foreign assistance,” as a Peace Corps staffer put it. Volunteers were part of the package, like it or not. Central Asia had no prior history with democracy — the region had been ruled by warlords and emirs before the Soviets came — and seemed more resistant to Western ideology than other parts of the Eastern Bloc. I felt as if the Peace Corps had violated its own mission — if not in letter, then in spirit — of sending trained men and women to “interested” countries, and that the U.S. government was using volunteers as pawns (not that we were very useful ones).

But if the president did not want us there, the Uzbek people absolutely did. They were eager to befriend us, to marry us, to watch our every move. I realized what my Peace Corps interviewer meant by “living in a fishbowl”; that was my reality. It was unsettling, but at the same time, oddly reassuring, because the surveillance added a layer of security. Local friends were the key to surviving. During training, I stayed with an Uzbek family and slept in a bedroom that had been surrendered by Babur, a son of the house who was named for a Mughul warrior. This modern-day Babur slept on the couch every night and said almost nothing to me during my stay. But he was a faithful guide and escorted me back to the training site each day after school. One night we arrived to the Maxim Gorky station when the power went off. He must have sensed my fear, because without a word, he took my arm and led me past the pickpockets and homeless men, the old ladies selling trinkets and buskers with tip jars who lined the dark passageways.

The first person to drop out of our group left the country before training was even finished. Once we got to our sites, the problems accelerated. Two women (one had been my roommate during training) were attacked after school in Andijan, a conservative city in the Ferghana Valley. After that, there was a constant stream of people leaving, both staffers and Volunteers. One Volunteer, living in Termez, a city on the Afghan border, got stoned as she was riding her bike through town. A middle-aged couple who had done a previous Peace Corps tour, got tired of bolting themselves behind a steel door: “This is not the Peace Corps,” they said, “We should not have to hide from the people we’re supposed to be helping.” They went home to California to live on their houseboat.

When I first moved to Samarkand, my site mate and I we were also targeted. We were living in a ground-floor apartment in a microrayon, an apartment complex in the Russian part of town. News of our arrival soon spread and one night, as we were preparing a teacher-training seminar, we heard a group of men gather outside the window. Then one of them reached in and drew the curtain aside while another tossed a flaming, sizzling bottle into the room. As they howled with laughter, we screamed for help and crouched in the hallway, frantically dialing the militia. Moments later, we decided to try to douse the firebomb ourselves before it exploded. Luckily, we succeeded. The next day, we returned to Tashkent and then spent the summer in the TDY (“temporary duty”) apartment there. All the women in our group were given the option of living in Tashkent for the duration of their service or transferring to a different Peace Corps country.

My friend decided to stay in Tashkent (she had a local boyfriend there), but I wanted to return to Samarkand. I didn’t want to be in the capital city with all the expats; it was enough to come once a month and get my stipend and gossip fix.

Bea picking cotton with her students

I managed to salvage my Peace Corps service, but it was nine months before I actually started teaching. The Peace Corps motto at the time was “The toughest job you’ll ever love”; my version was “the toughest job you’ll never do.” I loved my students at Samarkand State University; I visited their families, attended their weddings, and went cotton picking with them during the annual harvest. But my housing situation remained unstable and my living arrangements — there were seven or eight of them — ranged from homestays to borrowed apartments to a porch overrun by chickens. (Yes, I got salmonella while I was there)

Despite all, I developed a deep connection with the Uzbek people and became fascinated by the country’s history and culture. I’d wander the crooked streets of Samarkand and found a cockfight on the street corner as daily calls to prayer echoed through the air. At the old bazaar, I’d haggle for torpedo melons and spice cones, round bread and fabric bolts. I was awe-struck by the ancient monuments I saw all around me in Samarkand. Tamerlane, the fourteenth-century Central Asian warlord, brought the world’s finest artisans to design the city’s fabled turquoise tiled mosques and madrassas. Living in a center of ancient civilization put U.S. history into its proper perspective.

It was equally intriguing to learn how local people viewed current events. I spent a few weeks with a Tajik family that had two girls with flower names — Nargeeza for daffodil and Lola for tulip. Their mother Natasha was an elementary-school English teacher who explained to me over tea one day that Mikhail Gorbachev had been an idiot for putting political before economic reform, and that China was right to prioritize the economy first. Up until then, my perspective had been the standard Western one: that Gorbachev was a hero (he’d been on the cover of Time magazine, after all.) Natasha also startled me by remarking that Uzbekistan was lucky that Russia had bested Britain in “the Great Game” — the nineteenth-century struggle for control of Central Asia. Russia, she pointed out, had modernized the country and educated women, and even thought Uzbekistan was poor, now that the Soviet Union had collapsed, she felt that life was much better there than in the slums of Africa, which Europeans had colonized.

It was to such Third World countries, as they were then known, that Peace Corps Volunteers were originally sent in the 1960s. European powers had been pulling out, and as the countries became independent, they suffered from the strains of decolonization. A similar process played out in the 1990s, when the Soviet Union withdrew from the Eastern Bloc and the national republics throughout its sprawling territory. But when the Peace Corps entered the Second World, as former Communist countries were known, it operated differently, its mission morphing from cultural exchange to capitalism 101. Volunteers in our group spoke of feeling like test balloons for businesses seeking to expand to new markets.

Because of all of the problems with our group, we were granted a special dispensation to COS at the two-year mark, rather than the standard 27 months. At that point, 37 volunteers had quit — for reasons ranging from rape to death threats, broken hearts and mental breakdowns (quite a few were “psycho-vacced” as I recall) — leaving only 17 of us still in country.

Our group was dubbed Uzbek Zero (instead of Uzbek One) because the pilot program had failed to get off the ground until subsequent groups arrived with better training and resources. The Peace Corps’s blitzkrieg throughout Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union — 18 new country programs were opened from 1989 through 1993, the agency’s largest expansion since the 1960s — was not without collateral damage, mostly borne by volunteers.

The morning I left Samarkand, headed home, a little girl I knew (from visiting her elementary school) showed up at the airport to give me a gift. She approached shyly and told me she had made something for me. It was a doily with my name in big block letters (B-E-A-T-R-I-C-E) embroidered at the center, with strings leading off in every direction, like one of the designs created by the barn spider in Charlotte’s Web. I thanked my little friend, and, blinking back tears, turned to board my flight.

The Peace Corps was kicked out of Uzbekistan in 2005, after the U.S. (and other countries) condemned a massacre carried out by troops in Andijan — the same place where American women from my group had been attacked years before. Hundreds of people had gathered in the town square to protest poverty and political oppression, only to be cut down by their own government in what was later known as the Andijan massacre. In 2016, the country’s first president, Islam Karimov, died after 25 years in office. His successor, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, has demonstrated a more open foreign policy, and there are hopeful signs that positive changes are underway. Last I heard, the Peace Corps was negotiating to restart its program in Uzbekistan.

•

Bea Hogan (Uzbekistan 1992-94) is a writer and editor who lives in New Jersey with her family. After the Peace Corps, she worked in publishing for many years but has recently switched to advertising. Her time in Uzbekistan spawned a lifelong interest in the region, and she eventually got her masters in international affairs at Columbia University, with a regional focus on Central Asia. In 2001, she traveled back to Uzbekistan on a journalism fellowship and visited her old friends in Samarkand.

Read another essay by Bea at this site “Samarkand Calling.”

A fascinating account of your challenge in Uzbekistan. As a diplomat serving under SecState Jim Baker, I remember hearing about the push to “off-load” hundreds of Peace Corps Volunteers into the former Soviet nations. “What could possibly go wrong?…” Essentially the same thing was happening at the State Department in opening embassies in all of these nations. That also did not go very well. I’m glad you seemed to have made the most of it.

Thanks Michael! I think our group had an unusually close relationship with the embassy staff because we were virtually the only Americans in Uz those years. I loved seeing George Kent testify at Trump’s first impeachment trial in his crooked green bow tie. He was a young FSO, first tour in Uz, as I recall. Really interesting to hear what was happening inside State.

Bea—-Thanks fro the insights on being part of Uzbekistan “Zero”—a tough assignment and opportunity, no doubt about it. Tough assignments are not unusual in PC’s early days in any country, but former soviet countries must have been doubly tough, a puzzle wrapped in an enigma with mysteries galore. But to those who could and did remain in-country and did their best to live and serve with the people, it is an experience beyond compare.

i spent some time in Uzbekistan with an NGO in 2002-3 and found it a fascinating country. a couple of impressions beyond the architectural and historical wonders of Samarkand:

a) women had been granted more freedom to enter the respected professions and play a public role under the old soviet system, than they had in the USA. In terms of women’s opportunities the communist system was at least one whole generation ahead of the US—engineers, doctors, high levels managers, provincial governorships, politburo seats all open to women.

2) the growing of cotton on a grand scale was a result of the US Civil War, the blockade of the southern ports and the demand for cotten caused Czarist Russia to foster cotton growing all throughout southern Uzbekistan.

Thanks John! It was, on balance, a wonderful, unforgettable experience, which I appreciate more and more as the years go by. I know about cotton/water politics and Soviet women, both fascinating aspects of that culture.

[…] willingness to jump through their hoops.) The agency – perhaps unsurprisingly – often prioritizes politics over their stated mission. There are many accounts of the organization’s racism and failure to appropriately handle sexual […]