60 Years Ago Today — October 14, 1960 — THE UNKNOWN STORY OF THE PEACE CORPS SPEECH

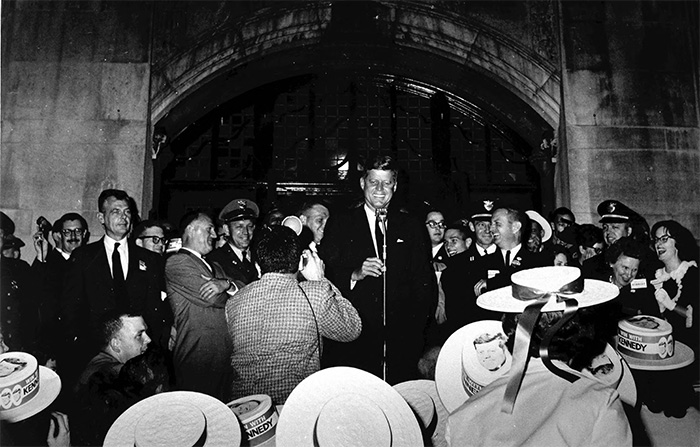

JFK at the Michigan Union – photo by Eck Stanger

JFK AT THE UNION

By James Tobin

Well after midnight on October 14, 1960, presidential candidate John F. Kennedy arrived at the steps of the Michigan Union. Legend has it that he first proposed the idea of the Peace Corps here. The truth is a little more complex, but far more interesting.

Senator John F. Kennedy’s motorcade rolled into Ann Arbor very early on the morning of Friday, October 14, 1960. The election was three and a half weeks away. The Democratic nominee for president and his staff had just flown into Willow Run Airport. A few hours earlier, in New York, Kennedy had fought Vice President Richard Nixon, the Republican nominee, in the third of their four nationally televised debates. The race was extremely close, and Michigan was up for grabs. Kennedy’s schedule called for a few hours of sleep, then a one-day whistle-stop train tour across the state.

The campaign got word that students had been waiting outside the Michigan Union, where Kennedy was to spend the night, for three hours. As the cars reached the corner of State and South University, Kennedy’s speechwriters, Theodore Sorensen and Richard Goodwin, looked out the window. Students, densely packed, were milling all over the steps and sidewalks and into the street. Some carried signs or wore Kennedy hats. There were signs for Nixon, too. Cries arose as the cars pulled up.

“He won’t just let them stand there,” Sorensen told Goodwin. “He’s going to speak. Maybe that’ll give us a chance to get something to eat.”

They hadn’t prepared a speech, but Kennedy was good at extemporizing in a pinch. He might have given the students a quick greeting and a standard pitch for votes. No one knows why he chose, instead, to ask them a question that would launch the signature program of his administration and ignite the idealism of a generation.

Since early in the campaign year, there had been scattered proposals for a volunteer corps of young Americans who would go abroad to help nations emerging from colonialism in Africa, Asia and South America. Kennedy had asked for studies of the idea, including from Samuel Hayes, a U-M professor of economics and director of the Center for Research on Economic Development. In early October, his staff had floated the idea in a press release, but no sparks had been struck. And Kennedy, according to aides, had been leery of the idea, fearing the damage Nixon might cause, in the jittery atmosphere of the Cold War, by calling him naïve about foreign affairs.

Possibly it was a remark of Nixon’s that drew Kennedy’s mind back to the idea. In the debate the night before, the vice president had reminded the national audience that three Democratic presidents—Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman—had taken the U.S. to war. Kennedy may have wanted to strike a note that would associate his campaign with peace.

In any case, he did not actually propose a program. He issued a challenge.

Speaking into a microphone at the center of the stone staircase, with aides and students around him, Kennedy began by expressing his “thanks to you, as a graduate of the Michigan of the East, Harvard University.” (A recording shows that this got a shout from the crowd.) The campaign, he said, was the most important since the Depression election of 1932, “because of the problems which press upon the United States, and the opportunities which will be presented to us in the 1960s, which must be seized.”

Then he asked his question:

How many of you who are going to be doctors are willing to spend your days in Ghana? Technicians or engineers: how many of you are willing to work in the Foreign Service and spend your lives traveling around the world? On your willingness to do that, not merely to serve one year or two years in the service, but on your willingness to contribute part of your life to this country, I think will depend the answer whether a free society can compete. I think it can. And I think Americans are willing to contribute. But the effort must be far greater than we’ve ever made in the past.

Therefore, I am delighted to come to Michigan, this university, because unless we have those resources in this school, unless you comprehend the nature of what is being asked of you, this country can’t possibly move through the next 10 years in a period of relative strength.

He said he’d come to Ann Arbor merely “to go to bed”—drawing a ribald roar from the crowd—then: “This is the longest short speech I’ve ever made, and I’ll therefore finish it.” The state had not built the university “merely to help its graduates have an economic advantage in the life struggle,” he said. “There is certainly a greater purpose, and I’m sure you recognize it.” He was not merely asking for their votes, but for “your support for this country over the next decade.”

The students roared again. Then Kennedy went up to bed, telling an aide he appeared to have “hit a winning number.”

There were 50 or 60 reporters with Kennedy, but few mentioned the senator’s remarks. Russell Baker of the New York Times reported that during JFK’s entire swing through Michigan, he said “nothing that was new” — which was true, if one counted the early-October press release. But in the aftermath of the speech, something new began.

The following Tuesday, October 18, Congressman Chester Bowles of Connecticut, a Kennedy supporter and advisor, spoke to students in the Union ballroom. He, too, proposed what the Daily called “a U.N. civil service, which would send doctors, agricultural experts and teachers to needy countries throughout the world.”

Among Bowles’ listeners were two married graduate students, Alan and Judy Guskin. From Bowles’ talk, they went to a diner where they drafted a letter to the Daily on a napkin. The letter was published the following Friday. The Guskins noted that Kennedy and Bowles had “emphasized that disarmament and peace lie to a very great extent in our hands and requested our participation throughout the world as necessary for the realization of these goals.” The two then pledged to “devote a number of years to work in countries where our help is needed,” and they challenged other students to write similar pledges to Kennedy and Bowles. “With this request,” they wrote, “we express our faith that those of us who have been fortunate enough to receive an education will want to apply their knowledge through direct participation in the underdeveloped communities of the world.”

Over the next two weeks, events moved fast. The Guskins were contacted by Samuel Hayes, the professor who had written the position paper on a youth corps for Kennedy. Together, they called a mass meeting. Some 250 students came out to sign a petition saying they would volunteer. Hundreds more signers followed within days.

Then Mildred Jeffrey, a Democratic state committeewoman and UAW official whose daughter attended U-M, got word to Ted Sorensen about what Kennedy and Bowles had wrought in Ann Arbor. Sorensen told Kennedy.

On November 2, in a major address at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, Kennedy formally proposed “a peace corps of talented young men and women, willing and able to serve their country…for three years as an alternative or as a supplement to peacetime selective service.” (Nixon responded by calling the idea “a cult of escapism” and “a haven for draft dodgers.”)

On Sunday, November 6, two days before the election, Kennedy was expected at the Toledo airport. Three carloads of U-M students, including the Guskins, drove down to show him the petitions. “He took them in his hands and started looking through the names,” Judy Guskin recalled later. “He was very interested.”

Alan asked: “Are you really serious about the Peace Corps?”

“Until Tuesday we’ll worry about this nation,” Kennedy said. “After Tuesday, the world.”

Two days later, Kennedy defeated Nixon by some 120,000 votes, one of the slimmest margins in U.S. history. Some argue the Peace Corps proposal may have swayed enough votes to make the difference.

“It might still be just an idea but for the affirmative response of those Michigan students and faculty,” wrote Sargent Shriver, JFK’s brother-in-law and the Peace Corps’ first director, in his memoir. “Possibly Kennedy would have tried it once more on some other occasion, but without a strong popular response he would have concluded the idea was impractical or premature. That probably would have ended it then and there. Instead, it was almost a case of spontaneous combustion.”

Alan and Judy Guskin were among the Peace Corps’ early volunteers. They served in Thailand.

≈

Sources include articles in The Michigan Daily and the Ann Arbor News and the following books: Robert G. Carey, The Peace Corps (Prager, 1970); Richard N. Goodwin, Remembering America (Little, Brown & Co., 1988); Gerard T. Rice, The Bold Experiment (Notre Dame, 1985); Karen Schwarz, What You Can Do For Your Country: An Oral History of the Peace Corps (Morrow, 1991); Sargent Shriver, Point of the Lance (Harper & Row, 1964); Theodore C. Sorensen, Kennedy (Harper & Row, 1965); Harris Wofford, Of Kennedys and Kings (FSG, 1980).

James Tobin is an author and historian. His most recent book is To Conquer the Air: The Wright Brothers and the Great Race for Flight.

This narrative is what I remember happening. We were living in California at the time and the U Mich speech really didn’t get much play in the California press. The Cow Palace extravaganza was the occasion of the first mention of a “Peace Corps” I can recall. Thereafter, there were many stories about the idea’s genesis and announcement.