“The Peace Corps Radicalized Me” by Thomas Pleasure (Peru)

The following article was published on Argonaut Online — the web presence of The Argonaut, a local newspaper for the westside of Los Angeles — on June 1, 2016 under the title “Opinion Power to Speak.” We are delighted to have received permission from the author to repost it here.

•

Sen. Robert Kennedy (surrounded by Peace Corps staff as well as American and Peruvian officials) reaches up to shake the hand of a young man in the slum of Comas, Peru, during a tour of impoverished communities in Latin America. This is the first publication of the Nov. 12, 1965, photograph taken by then-Peace Corps Volunteer Thomas Pleasure.

•

The Peace Corps Radicalized Me

by Thomas Pleasure (Peru 1964–66)

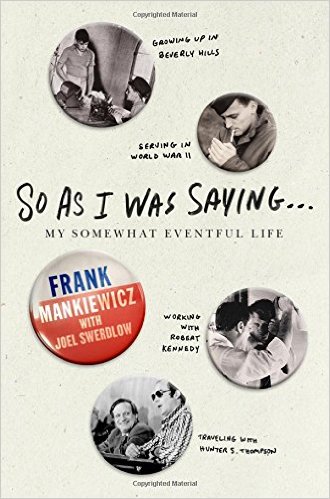

SINCE FRANK MANKIEWICZ’S DEATH in 2014, activists, historians, cineastes, journalists and spinmeisters had been awaiting  publication of his posthumous memoir, So As I Was Saying . . . My Somewhat Eventful Life. I imagine we all felt that Frank — son of “Citizen Kane” writer Herman Mankiewicz, nephew of director Joseph Mankiewicz and a political force of the 1960s and ’70s in his own right — had a special message for us.

publication of his posthumous memoir, So As I Was Saying . . . My Somewhat Eventful Life. I imagine we all felt that Frank — son of “Citizen Kane” writer Herman Mankiewicz, nephew of director Joseph Mankiewicz and a political force of the 1960s and ’70s in his own right — had a special message for us.

We were right.

Movie buffs will lap up Frank’s tales of growing up in Hollywood and his conversation with Fidel Castro about Jaws. His decades at Hill+Knowlton are presented as McLuhan-esque case studies. True to form, his punch-line ending summarizes the anomalies surrounding President Kennedy’s murder, casting further doubt in the official storyline of a lone assassin. The one constant in his 90-year life, it seems, was an abiding love of words.

That’s half of Frank’s book. I’m interested in the other half, which covered his time with Robert F. Kennedy and the Peace Corps.

Now writing about my life as a working-class activist, I needed to know Frank’s take on the turbulent events of the 1960s. Frank was there at the beginning of my life of activism. He was the first American I ever heard speak of “revolution.” It was the summer of 1964. I was in a Peace Corps training program awaiting deployment to Peru, and Frank, then head of the Peace Corps’ efforts in Peru, told our group of 102 that we would be “fomenting revolution by empowering the poor.”

Frank is clear about the Peace Corps’ role in Latin America and in his own life: “We trained volunteers to be community organizers,” he writes. “The Peace Corps radicalized me.”

Serving in the Peace Corps began my radicalization as well.

After Frank was made the Peace Corps’ director for Latin America, he attended a briefing about a fact-finding tour of the region being arranged for newly elected Sen. Robert Kennedy. LBJ’s people at the State Department had clearly reverted away from the policies of President John F. Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress, writes Frank, who suggested that Kennedy visit a barriada on the outskirts of Lima to see the poverty of Peru up close.

Frank did not accompany Kennedy to the ramshackle Comas district in Peru, where I briefly saw him, but Kennedy so appreciated his help that he made Frank his press secretary. It was an honor that, just a few years later, gave Frank the heartbreaking duty of announcing Kennedy’s death to the press following his assassination on June 6, 1968 — 48 years ago as of this Monday — at the Ambassador Hotel.

Frank’s wisdom in directing Peace Corps Volunteers to organize the disenfranchised had stunning results. Urged on by Peace Corps Volunteers, an Andean-born shoeshine boy named Alejandro Toledo headed to America to get a university education and would go on to displace corrupt leadership as Peru’s first indigenous president.

Only los gringos del Cuerpo de Paz would be so audacious to help the poorest of the poor. We should thank Frank Mankiewicz for having the cajones to foment social change in the southern hemisphere of which Americans can be proud.

Years later, after Kennedy announced his bid for the presidency in March 1968, he was flying into Los Angeles and I decided to meet his arrival at LAX’s TWA terminal. I brought my five-month-old son along and carried him on my back. When Kennedy disembarked it was the first and only time in my life I was swept off my feet in a stampede of a people. Not being able to touch the floor and being forced to go with the flow was unsettling but at the same time exciting.

Frank’s book delves into Kennedy’s campaign efforts in California. Hundreds descended daily on the campaign headquarters at Hauser and Wilshire boulevards. There weren’t enough opportunities for people to get involved.

I jumped in full time and formed Young Professionals for Kennedy to corral volunteers; we organized Kennedy coffee klatches throughout Los Angeles County — probably 700 of them in all, each with the purpose of discussing his book To Seek a Newer World. If you had a dozen or more confirmed guests, we provided a speaker; the more confirmed guests, the more well-known the speaker.

I jumped in full time and formed Young Professionals for Kennedy to corral volunteers; we organized Kennedy coffee klatches throughout Los Angeles County — probably 700 of them in all, each with the purpose of discussing his book To Seek a Newer World. If you had a dozen or more confirmed guests, we provided a speaker; the more confirmed guests, the more well-known the speaker.

Frank was at the top of the campaign pyramid. We never spoke directly. His secretary would funnel my requests for celebrity speakers to him and his requests to me — things like “arrange to pick up the senator’s children at LAX.”

Besides the klatch I held in my West L.A. duplex, I was so busy organizing them that I went to only one other. It was late in May at a beach house on the Marina Peninsula, where a brouhaha had erupted and all kinds of celebs showed up in a battle between Sen. Eugene McCarthy and RFK supporters. Not only did I go, so did Frank.

After the 60 guests had left, sitting around the kitchen table with Frank was Venice High School’s most famous graduate, Myrna Loy. They were not discussing the campaign, but their belief that Hollywood made its best movies after World War II ended in 1945 up through 1948 — films such as The Lost Weekend, Gentlemen’s Agreement and The Treasure of Sierra Madre.

At the time I didn’t know what Frank and Myrna were talking about. I was from blue-collar San Berdoo; what did a railroad switchman-turned-activist know about film censorship? But Myrna and Frank knew firsthand how much had changed in the movie business after Sen. Joe McCarthy’s red-baiting attacks forced Hollywood to knuckle under.

Overhearing the laments of Frank and Myrna in 1968 led me to decades of watching Turner Classic Movies and to the sad realization that Americans, artistically speaking, are not as free as we once were.

Despite the vast differences in our age, our wealth and our roles in Robert Kennedy’s presidential campaign, in the end both Frank and I identify our very brief sliver of time with RFK as “the high, promising moment of our lives.”

•

Thomas Pleasure, is a Venice-based writer and activist. He is hard at work on his memoir, Autobiography of an Activist: A Serendipitous Journey from Brooklyn to Venice Beach.

To order any of the books mentioned here from Amazon, click on the book cover, the bold book title or the format of the book you prefer— and Peace Corps Worldwide, an Amazon Associate, will receive a small remittance that will help support the site and the annual Peace Corps Writers awards.

Beginning last year, I began to be interested in what brought about the transformation of RFK from McCarthy aide and super rich kid family background to the progressive he became and the threat to the FBI and the right wing he ultimately became, inviting his assassination. Any books, writings, in addition to Pete Hamill that you can recommend?

How I found this article: looking up RFK’s trip to Peru in 19656. I grew up in Lima and attended Colegio Americano (Franklin D. Roosevelt School) 1956-1963. It was in Lima that I first became involved in a political campaign (Fernando Belaunde Terry), and where I first was exposed to excruciating poverty and became aware of the communist party appeal to the very poor.