The One Word That Almost Sunk the Peace Corps

THE ONE WORD THAT ALMOST SUNK THE PEACE CORPS

BY EMILY CADEI

OZY Writer

MAY 15, 2015

When John F. Kennedy asked young Americans in 1960 how many of them were willing to spend years in the developing world “working for freedom,” he surely had people like Marjorie Michelmore in mind. What he couldn’t have anticipated is how the young Marjorie almost sent his whole vision for the Peace Corps up in smoke.

Michelmore had just graduated magna cum laude from Smith College when she was selected for the inaugural class of Peace Corps volunteers in 1961. It was a pet project of Kennedy’s, a concept he first broached at a morning campaign rally at the University of Michigan in October 1960, after arriving several hours late. Thousands of students had waited for him – a sign of how much Kennedy excited young people back then. And he, in turn, was excited to tap into their potential to spread American culture and values throughout a rapidly changing world.

Empathy was the bridge back then, and it remains a central feature of the Peace Corps mission today.

In the second month of his presidency, Kennedy signed an executive order creating the Peace Corps, and Congress passed a law later the same year authorizing the agency to “promote world peace and friendship.” It was a bold experiment in “giving extraordinary trust to young people, partly in the context of the whole Kennedy administration, itself, being youngsters,” says Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman, a historian at San Diego State University and author of All You Need is Love: The Peace Corps and the Spirit of the 1960s.

The idea attracted its share of critics who questioned the idealism of the concept and the capacity of young people to conduct the hard work of development and diplomacy. Kennedy’s presidential opponent, Richard Nixon, condemned it as a potential “haven for draft dodgers,” according to a 1960 article from theHarvard Crimson. And the cadre of professional diplomats in America’s foreign service had their misgivings as well.

Which explains why a postcard Michelmore wrote to her boyfriend from her Peace Corps teacher training at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria became such a flash point. America may have been transitioning, but think what Nigeria was experiencing – as a new nation just granted independence from Britain the previous October. It was part of a huge swath of the African continent casting off colonial rule and testing new forms of government and self-empowerment.

So imagine Nigerians’ embarrassment at what Michelmore wrote on the postcard, which she accidentally dropped before mailing. It landed in the hands of a Nigerian student and then on the front pages of the country’s newspapers – and later the world’s. “We really were not prepared for the squalor and absolutely primitive living conditions,” she wrote, noting how she’d “had no idea what ‘underdeveloped’ meant.” She went on to say that it’d been “a very rewarding experience,” but the damage was done. For Nigerians, so proud of their new country, the “word ‘primitive’ was as insulting as anything anybody could say,” says Hoffman. Students launched protests that turned into riots. A distraught Michelmore had to flee the country. “I possibly thought I might have wrecked the whole Peace Corps idea,” she later recalled in Smith’s alumni magazine.

In the end, of course, the Peace Corps survived, not the least because of the grace and perseverance of Michelmore, her colleagues, their Nigerian hosts and Kennedy himself. When Nigerians demanded the program be expelled from their country, another American volunteer “went on a modified hunger strike,” Hoffman says, refusing to eat unless he could dine with the Ibadan students. At a time when parts of the United States – including Washington, D.C. – were still racially segregated, that kind of gesture resonated. Michelmore apologized to Nigeria’s leader before leaving the country, and on her way home she received a cable from Kennedy thanking her for her “steadfastness” in the face of turmoil. “We are strongly behind you and hope that you will continue to serve in the Peace Corps.” She did, working for the program in D.C. the following year.

The episode was a wake-up call for the young agency about how sensitive it needed to be to cultural differences. People like Michelmore, Hoffman says, were “very well-trained, they were people who were trying to be different.” But they were also young and living in a very different time, uninitiated by today’s modern communications, which have brought us face-to-face with world cultures. “I think it is the context, more than the Peace Corps itself, that’s evolved,” says Hoffman, noting that the agency was responsible for introducing “culture shock” into the American lexicon.

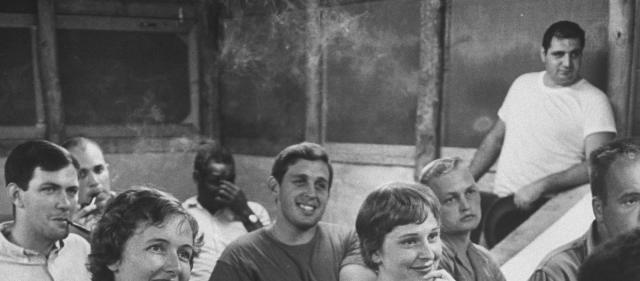

Margery speaking to Trainees in Puerto Rico, photo was taken by renowned photojournalist, Carl Mydans

But empathy was the bridge back then, and it remains a central feature of the Peace Corps mission today. At a recent event, Director Carrie Hessler-Radelet emphasized how important compassion is to the organization’s efforts, highlighting how the agency responded to the sexual assault of its volunteers. “I don’t think I’ve ever met such incredibly dedicated, hardworking, compassionate people who care deeply about world peace,” she said. The Peace Corps, she noted, “attracts people like that and always has.”

To Hoffman, that kind of compassion started “at the very top of leadership” in the program’s early days, when a president with a lot at stake responded to an unintentionally scandalous postcard with a gesture of kindness.

You can read more about Margery Michelmore at: https://peacecorpsworldwide.org/in-some-ways/

- Emily Cadei

Emily covers government, world affairs, business and sports for OZY. California-bred and D.C.-based, she’s reported from four of the world’s seven continents – still waiting for a byline from South America, Australia and Antarctica!

I am impressed that a Smith magna cum laude graduate had so little an understanding of the country and culture where she was to serve. I believe most of us had a good idea of what we would encounter in our countries of service.

I would offer one thought, in the 1960s college graduates had no problem finidng jobs and we knew that taking a couple years off to experience the world would not seriously lessen our chances in the job market. I believe today’s college graduates face a more stark reality in which one has to do an all out press to just enter the job market. That may be reflected in the low application rate.

It was, of course, a foolish postcard to write, and I suppose she had to be punished for it. But I have always felt that her mistake was exaggerated and that she had not damaged the Peace Corps as much as many thought. I spent three months at the university later that year and found many students embarrassed by their over reaction. Few would disagree with her description of the streets of Ibadan, one of Africa’s few indigenous cities. But they did not like an American putting it down on an open post card. I have to agree with Warren Wiggins who felt that the Peace Corps was lucky that its first scandal — the one that made headlines across America — centered on a postcard about people peeing in the street. Juicier scandals that came later did not get the same attention.

I was one of the Peace Corps trainees in the first picture you showed. We had just begun our training at the Peace Corps facility in Arecibo for assignment in Sierra Leone and Marjorie was brought from Nigeria to our training camp to keep her out of the press spotlight. Shriver did not want the postcard story to blow up any further. Three years later I met Marjorie again at Columbia Teachers College where she was working as secretary to the Director of the Peace Corps Training Programs for Nigeria. She was then using her married name and none of the trainees knew that she was the Marjorie Michelmore who had dropped the infamous postcard a few years earlier. She was a wonderful woman.

I would also surmise that the discontent that exploded with the postcard incident would have been brewing ahead of time, and that the postcard itself was more of a trigger than the sole reason for the protests. It does make for interesting comparisons with today’s volunteers blogs, though.