“The Nzeogwu I Knew” by Tim Carroll (Nigeria)

Editor’s Note: In February 2015, Roger Landrum (01) 1961–63, in the email below, alerted the newsletter staff of what he believed to be an interesting story about a friendship that had developed in Nigeria in 1965 between Peace Corps Volunteer Tim Carroll and a young major in the Nigerian army.

Jim.

I recently read Achebe’s Biafra memoir, There Was a Country. It has a brief section on Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, one of the five military majors who led the coup that triggered the chain of events leading to the Biafran secession and the civil war. Achebe calls Nzeogwu “a mysterious figure.”

Maybe not all that mysterious! There was a Nigeria PCV named Timothy Carroll posted in Kaduna who was friends with Nzeogwu. I’m trying to convince Carroll to write a piece for the FON newsletter called “The Nzeogwu I Knew.” I think Nigeria RPCVs would find this fascinating. It will also help fill out the picture of the “mysterious” Nzeogwu for a period of Nigerian history in which this new generation of Nigerians has an intense interest. — Many thanks, Roger Landrum (01)(1961–63)

Carroll was prompted to share his memories and has done so in, “The Nzeogwu I Knew,” which appears below.

— Jim Clark

•

The Nzeogwu I Knew

by Tim Carroll (group 09) 1963–65

•

Meeting Chick

Aware that as a Peace Corps Volunteer I had gotten to know and developed a friendship with Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, the leader of the ill-fated coup of January, 1966, Roger Landrum (02) 61-63, a friend, ace of Nigeria’s second PCV group, and keeper of the keys, read There Was a Country, Chinua Achebe’s last book, and subsequently sent these excerpts about the Biafran war for my attention:

Historians have argued incessantly about the makeup of the January 15, 1966, coup and its meaning. It was led by the so-called five majors, a cadre of relatively junior offcers whose front man of sorts was Chukwuma Nzeogwu. Very few people outside military circles knew very much about him. What I heard was what his friends or those who happened to know him were telling us. He seemed a distant, mysterious figure. Nzeogwu had a reputation as a disciplined, no-nonsense, non-smoking, non-philandering teetotaler, and an anti-corruption crusader. This reputation, we were told, served him well as the chief instructor at the Nigerian Military Training College in Kaduna, and in recruiting military ‘intellectuals’ . . .. Superficially it was understandable to conclude this was indeed ‘An Igbo coup.’ However . . . one of the majors was Yoruba and Nzeogwu himself was Igbo in name only. Not only was he born in Kaduna, the capitol of the Muslim North, he was widely known as someone who saw himself as a Northerner, spoke fluent Hausa and little Igbo, and wore the Northern traditional dress when not in uniform.

. . .

In the end the Nzeogwu coup was crushed . . ..

Reading the excerpts served as the necessary prod I needed to dig back into that era, July 1964 to July 1967, and put to paper my thoughts surrounding a friendship I had with this remarkable Nigerian.

•

My arrival in Nigeria was less than auspicious. It was New Year’s Day, 1964. I arrived alone, via London, because there wasn’t room on the plane when our two groups were combined into one. Someone with a clip-board met me at the airport in Lagos expressing great surprise to see me. Apparently, the project in Western State for which I had been prepared by studying Yoruba throughout training at UCLA in the autumn of 1963, had been cancelled. Washington had been notified to hold me back, but there I was.

The beauty of the early Peace Corps was that no one seemed unsettled by the mix-up. John Dodge, Peace Corps Director of the Northern State (63-64), stepped in and suggested I go with him and a group trained in Hausa to Kaduna. After three days in muggy Lagos, I stepped out of the plane in Kaduna on to a step ladder and into that hot, dry, scented winter air of the savannah known as the Harmattan; I knew I was home. Within a week I was happily ensconced at the Schools’ Broadcast- ing Unit of the Ministry of Education, Northern Nigeria, which housed both radio and television production facilities. Dodge, an able organizer, had heard they were looking for someone with my background and it was all settled very quickly to everyone’s satisfaction, none more than my own.

Tim and cast of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

My job included writing, directing, and producing educational television programs for schools in the North. It was a newly initiated program with state-of-the-art facilities, designed to reach secondary schools in that far-flung territory. My fare over two years was as diverse as teaching English (with a puppet), hosting such programs as “Our African Neighbors” and “The Thinking-Cap Quiz,” dramatizing the four Shakespearean plays that were the set books of for 1964 and other assorted academic ventures for the air-waves. It was, by any measurement, a sweetheart assignment.

Kaduna, long the colonial head-quarters and now the provincial capital of the Northern State, was the hub of the region, a lively arena bustling with energy and enthusiasm. The British, with their special affection for the Hausa, had been gone for five years and our cadre of Volunteers sensed we just might be the logical bridge between them and an effective working Nigerian democracy that we hoped lie just ahead.

Major Chukuma Kaduna “Chick” Nzeogwu in 1965

Because of the reach of our programming at the Ministry of Education, it wasn’t long before I got to know a number of people from a collection of diverse communities, among them the Irish missionaries who had an extensive educational network even in the Moslem North. Their bishop was headquartered in Kaduna, and I was a regular at his Mass. One Sunday in the middle of my first year (July, 1964) at the social hour (did a Volunteer ever miss any opportunity for a free doughnut?), he took me by the arm and steered me toward a sharply dressed army officer. He chuckled because he thought we would both have met our match. And that is how Patrick Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, lf “Chick” to his friends, and I originally met. And the bishop was right. Chick’s humor seemed very Irish to me, and he complimented me on being as funny as an Igbo. In a letter home that month, I described him as “twenty-eight-year-old major in the Nigerian Army, a militant rebel, a Roman Catholic and a romantic . . . a difficult but fascinating fusion.”

Over Fanta soft drinks, we discovered that my house, with a sign “The New Frontiers Club” hung on the veranda by an earlier Volunteer, was just down the road from the Army’s Cadet School where Chick worked with young recruits headed for the Officer’s Corps. I shared with him that I drove past them on my way to work in the mornings and remarked at how carefully they attended the crossing of the road, always careful to look both ways, a decidedly un-Nigerian approach. We agreed that it bode well for the future leadership.

Pulling up memories now 50 years old is a tough job, but I can recall that we immediately hit it off and soon had established a Sunday routine: Mass, then a meal at the Officers Mess followed by lively discussions in his quarters. His friendship also came with invitations to the film nights held regularly at the base. One which I remember we both liked and talked about at length was Dr. Strangelove which seems particularly poignant in retrospect. Early on, Chick invited me to a reception at the Officers Club. I brought Katy Rosentreter Lapp (08) 64–66, a neighbor and friend from our Peace Corps group. That evening Chick introduced us to his friend and fellow officer, Wale Ademoyega. Wale would play a central part in events to come.

Tim in 1965 riding one of Nzeogwu’s favorite horses.

When the cooler weather arrived, Chick and I added an afternoon horse-back ride to the agenda. The officers had a saddle club on the base and Chick kept his horses there. I always marveled that after a couple of hours of brisk riding, crossing the river and various gullies and gorges, we would be in territory seldom visited by Europeans since nothing vehicular could have made it into the area and the bature (foreigner/white man) rarely thought to walk such a distance. In letters home I described two incidents from these rides.

One afternoon, about as far into the hinterland as we could go and still return before dark, I heard a tune wafting through the air that I recognized. We walked the horses into a small village and there, issuing forth from a wireless radio was the voice of Gene Autry singing, “I’ve got spurs that jingle, jangle, jingle.” We laughed about how Chick might change his career to that of a cowboy.

Another time we had ridden into the Gwari area inhabited by people who, at that time, were still animists. They were performing funeral rites on an elder, and we watched from a respectful distance until it was over. It was their custom to bury their dead in an upright position, and we watched as the body was carefully covered over, leaving a small mound above the ground. Chick spoke in Gwari to the head man, and we dashed them a few shillings according to the dictates of the time. Later, when we stopped to water the horses, Chick said they would attach some supernatural connotations to our riding in at that moment, and it would be a juncture in their lives from which they would date events.

During my last two weeks in Kaduna, December, 1965, Chick had to be away on military business. At a little farewell party he asked me if I would exercise the horses in his absence. I agreed and every evening I would ride out into the savannah taking different routes each time and recalling memories of our earlier outings. After one such ride, I wrote this home:

. . . but tonight I just rode along the ridge and watched the sun slip into the red bank of the Harmattan and saw it grow larger and redder until it looked as if it would explode and then sadly, silently, just above the horizon, disappear in the haze, like a stone in ooze. It’s melancholy to watch it go like that, but the fireflies come immediately it’s gone and they guide you back to the stables. for the last time.

Shortly before the end of December 1965, my Peace Corps service having come to an end, I left Nigeria via a coastal freighter departing from Lagos and puttering up the coast to Casablanca spending Christmas 1965 there. After the holidays, I hitchhiked along the coast of the Mediterranean eventually reaching Cairo. It was there that I read about the Nigerian coup in Cairo’s Herald Tribune. According to the article, just after midnight on January 15, 1966, Major Chucwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu led a small detachment of hand-selected army rangers in a surprise attack on the compound of Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto, Premier of the Northern Region of Nigeria and arguably one of the most powerful religious and political figures in Africa. According to news reports, on that evening, after hearing a commotion outside, Bello came out from his private quarters to investigate when he was confronted by Nzeogwu and the rangers in his command and, in a hail of gunfire, was quickly assassinated.*

On that same evening, other coup plotters had attacked the residences of powerful political figures in Kaduna, Ibadan, and Lagos and also blockaded the Niger and Benue Rivers. When the coup was over, 11 senior Nigerian politicians and two soldiers lay dead and three others were kidnapped. News sources confirmed that Bello’s assassination was one part of a carefully coordinated attack planned and carried out by Nzeogwu and some of his fellow army officers.

It wasn’t astonishing for me to read that a military coup had taken place in Nigeria, but I was dumbfounded to find Chick at the head of it. Never in all the months I had known him had a word ever been spoken between the two of us about his planning or his participation in such an event. It had been obvious, however, that he hated the corruption, the lack of moral leadership, and the extravagant lifestyles lived by the powerful in total disregard for the welfare of most Nigerians.** He was especially fervent about his idea that Nigeria, as a united and well-governed country, could become a nation his fellow Africans would wish to emulate. But for this reverent, funny, buoyant, affectionate, competent leader of men to have initiated an event of this magnitude both stunned and, in truth, intrigued me.

Not knowing Chick’s fate or his whereabouts following these events, I returned to the States in March, 1966 determined to find a way to locate him. Fortunately, I had just been hired by Congressman [Billie] Farnum (D-MI) to work as his legislative assistant in Washington, and it was from those offices that I put my plan in place.

Finding Chick

Quickly realizing that a call from a Congressional office could stimulate a lot of second-hand smoke in the bureaucracies around Washington, I sought their help in locating Chick. Various desks at the State Department sent me a number of addresses they thought might work, all to no avail. I also reached out to a variety of friends and acquaintances back in Nigeria, but still had no luck in finding him.

Then I remembered Sister Liam! I should have thought of her first. Sister Liam was the head of Our Lady of Apostles School in Lagos and a force of nature. My great friend, Sam Abbott (09) 1963-65, had been assigned to teach in her school, and during our two years in Nigeria she had become a good friend of mine. As soon as I put her on the task, I got results. The Irish missionary network in Nigeria was like the Mafia on holy water, and in no time I had a letter from Sister with news from Chick; he was imprisoned in Lagos.

Sister Liam wrote to Chick and in July 1966, he responded with a note to her:

I am very grateful for your note requesting me to reply to Tim Carroll’s letters. You can rest assured that I will do so as soon as the Ironsi regime allows me to draw my own money in order to purchase air mail letter cards. I am able to reply to your note because you are within Nigeria thus enabling the prison authorities to forward my note without charges. Please extend my sincerest compliments to Tim when you write him and thank him on my behalf for his efforts in writing me twice [so the State Dept actually was helpful] and even enclosing a nice photograph. I pray that the Johnson Administration does not send him to Vietnam!

Shortly after writing Sister Liam, Chick was transferred to the federal prison in Enugu where, true to his word and as soon as he had my address and the cost of the postage, he wrote me. The letter is dated October 28, 1966:

My dear Tim,

Thanks for your several letters and messages thro’ Sister Liam. Please come back any day and I will welcome you . . .. What I am worried about is the great number of blankets that may be lost if all my American friends are keen jockeys! Boy oh, boy, did you not loose (sic) several at Kaduna? [He knew I only lost one, but he found it so odd and so funny that it became the source of a running joke between us.]

The forces of reaction are destroying themselves in Nigeria, but it is small comfort that some progressives are still alive even if behind the prison walls. As usual, Time and Newsweek do a lot of objective reporting and so you have probably got all the details by now. I won’t bore you with any more details but you can take it from me that the figures often reported are an understatement. Casualty figures may be in excess of half a million. [He is referencing the merciless Hausa attacks on Igbo’s throughout the North during this period.] In spite of that, I am not discouraged. If I am released and allowed to help build up my native Mid-West, whilst Ademoyega is doing the same thing in the West, we may be on the path of glory sooner than is generally thought. [Wale Ademoyega, as one of the five coup leaders, was unsuccessful in killing his target, but he joined Chick in Kaduna in the aftermath and was imprisoned with him for his attempt.]

Thank you for your kind offer of accommodation, if and when I visit the U.S. I am dying for an opportunity to see “Kennedyland” any day. I remember you trying to make me believe the results or findings of the Warren Commission one Sunday afternoon as we were relaxing at No. 13 Kanta Road [his quarters in Kaduna]. The current doubts being raised by people in the US goes to prove my point. Do you now see my point?

I don’t want you to go to Vietnam; I need people like you to come and help . . .

Bye now Tim and God Bless.

Chick.

The next letter I have been able to locate was written on December 22, 1966.

In November of 1966, the Congressman lost his election and I accepted a job in Pago Pago, Samoa, to start on January 1, 1967. I decided to go to Samoa via Nigeria so I could visit Chick. By that time he had been moved to Enugu in the Eastern Region. There was a flurry of exchanges. Again, Sister Liam rose to the fore. We both were in touch with Chick about the arrangements. He wrote:

My dear Tim,

If this letter reaches you before you leave the US you will be lucky . . .. Please come to Enugu and let me hope that you are allowed to come and see me. I have already applied to the Assistant Director to facilitate the call and there should be no difficulty. Please ensure that you go to his office early enough (8.15 a.m.) in the day as you will have to drive out possibly by taxi in order to see me in my location (149 miles away).

Good-bye now. I hope you had a happy Christmas! Wishing you a prosperous New Year in advance.

Yours Ever,

Chick

Tim’s photo of his travelling companions on the way to visit Chick at the federal prison in Enugu.

Sister was on top of things. She had organized the trip, bu road, with cars and drivers and with the time-table all worked out, even though the Biafra conflict was heating up. She was never known to fail in any mission she undertook. Unfortunately, on the day we were to depart Lagos for Enugu she was unable to accompany us and sent a rather more tame version of herself to carry out the task.

After some trials en route we were at the front of the prison, literally knocking on the door. But no amount of cajoling on my part, or that of the young nun with me, would move the prison director to let us in. He did, however, agree to take my bundle of gifts to Chick. When we returned to Lagos, Sister Liam was even more bereft than I was and for years lamented she hadn’t been there to make it happen.

Chick’s letter of Jan. 21, 1967 reached me in Pago Pago. Apparently he had been given enough money to send more than an “air mail letter card” since it consisted of four tightly written pages and it was the longest letter to have survived.

January 21, 1967, Enugu Prison

My dear Tim,

You are great. Thanks for the wonderful gifts.

I first heard of your visit from the priest who rightly guessed who you were, considering that we speak a lot about you, and he normally takes a peep into your letters. Well the whole tin gods in the prisons do, so why not my personal chaplain.

Mr. Osadebe, the Superintendent of Aba prison, is a particularly nasty man however honest he pretends to be. I tell it to him in his face as often as I can because it is true. If you could see Wale [on route to see Chick I had successfully visited Wale] at Warri, why was it made so difficult and impossible at Aba? I hope that you come again either when I am out or after mid-February when he would be gone. To give you an idea, this fellow turned my dad away last November even if we are all Mid-Westerners from Asaba. At that time as now, all prison authorities have been instructed to let our relatives see us whenever the request is made.

So are you really going into this neo-colonialist business [referring to my new job in American Samoa]; whatever you do, please stand clear of Vietnam. Go wherever you wish, but please come back to Nigeria . . .. People say that Johnson is a great president, but see the impact that JFK’s three years had on the rest of the world — Peace Corps, Alliance for Progress, US image, etc. We want RFK! I have nothing against Johnson, but I don’t want this bombing of N. Vietnam and the mayhem in the South. Johnson is putting aside MacNamara’s advice and listening to people like [Cardinal Francis] Spellman (War Vicar) and the Chairman of the Armed Service Committee who wants Hanoi flattened and “let world opinion go fly a kite.” Remarkable for people who should be giving us better advice. McNamara will join RFK/Fulbright team after 1968 or 1972. Whilst we are probing our own miscreants you people have your Adam Clayton Powells. He will find a job as a Nigerian Minister if Gowan turns over the government to the same old political criminals that my movement tried to evict from office.[The next reference related to a letter of mine to him earlier in December when I was trying to decide whether to take the job in Samoa or with the FCC which was on the table at the time.] The job in Washington (if you take it) should keep you permanently at home so I have a definite place to catch you. I love travelling as much as you do. Don’t stage a coup in the Commission, or at least, get my advice before you do! Ooh!! That savings bank that you have for me, Wonderful of you. What interest do you want on it? It is something to fall back on if…. (sic). Thanks

[On my way to visit him in the Enugu prison, I told him I had first gone to Kaduna for Christmas and to see old friends, including the officers I knew at their Saddle Club.] So you rode again with Tijani Katsina at the saddle club. He was with us in prison at Kiri-Kiri in January and February 66 but was let out by his compatriots after the July coup (or probably earlier). He must be a good rider now (drinker, too!). I have all the necessary outfit to keep me busy here, radio, books, papers (mostly imperialists ones) and that puzzle you added among the gifts. I dismantled that thing within 30 minutes of receiving it, but have not been able to as- semble it since. You Yankees are clever alright if the aim is simply to keep me and Wale busy until we are out of here. Now, as for Nigeria, we are heading for a confederal constitution in order to lessen the friction until tempers cool down. That is the least line of resistance, if the war lords agree, but if they fail to agree, they may require those of us in prison to help realign their political thinking. If you catch hold of a copy of Nigeria 66, the Gowan government official version of the January 15th putsch, you will understand what I mean. It is needless to tell you that the release is no more than a tendentious apologia by the July 29 executionist. I wished that what they wrote had any semblance with the truth. Wale is a historian whom I am sure will in his account separate fact from fiction. No sooner had my rebel camp been partially incarcerated than the Loyalist camp honeymoon ended. The poor chaps neither have an aim, national enough to receive general support, nor are they capable of leading us to such a goal. Nigeria will never be in order until those fellows all shamble back to barracks to get disarmed and disbanded. You can take this as my first and foremost aim and probably those of all right thinking men here. There must be a general onslaught against all corruption and vices during our foundation building for the 2nd Republic. What has been going on is a sham because people get exposed and no one gets chastised. Thanks to the bunglers operating with Wale in Lagos, our coup floundered and power found itself in the hands of the reactionaries. Old boy, it is now the pen, soap box and ballot box for me, if I get out from here, unless of course, I am invited back into the Mid-West fragment of the moribund Nigerian army. Either way, “there is no forbidding what God has given nor can be given what God has forbidden,” so says the great Ibn Fartua. [Ahmed Ibn Fartua was the chronicler for King Idris Alooma, 1542-c.1619, of the Bornu Empire. His written histories have survived. Chick was a great fan of this era which was centered around Maiduguri.]

I am glad Tim that Nigeria has such a hold on your imagination. Thanks to JFK maybe we might succeed in forging a superb relation to our nations’ mutual benefits. We (Africans) contributed part of the labour that built up the New World. There must be 25 million immigrants from our part of the world in USA alone.

About your current job, so these Yanks have TV at Samoa for educating the natives! I hope you are enjoying the work.I am so very grateful that you tried so much to see me. I will always remember . . .

[He adds our favorite joke as a post-script] You must have lost a few more (saddle) blankets during your jockey training at Kaduna on this last visit. I may use some of your money for pur- chasing blankets and presenting same to the saddle club in your name!

[And a second post-script] I have written on both sides of each sheet in order to keep down weight and cost, too. I am not usually so miserly!

The last letter I received from him was dated May 10, 1967. By this time I was well into the Samoan chapter of my life and had shared that saga with him in correspondence.

My Dear Tim,

Thanks for your last two letters giving details about life at Samoa. Right now, I could do with a holiday in such a paradise. One feels like he is in hell here and I look forward to your promised visit. No doubt, you have kept in touch with Nigerian affairs through the press and radio. We are back to square one except that the East is almost out of the Federation on account of Gowan’s bungling.

When do you return to the US Tim? As you spend so much time outside the US, U Thant might be pleased to offer you a job asa UN touring diplomat! That would be great.

Since my release from jail, I have been so busy and that accounts for the very few letters which I could write to friends. I am likely to be busier now even if the Eastern Government “granted” me compulsory leave today for an indefinite period. The leave will have to be spent around this place as I am unable to go to my native Mid-West for obvious reasons. [As an opponent to the break-up of Nigeria, Chick had publicly disagreed with his former colleague, now Military Governor, Lt.-General Ojukwu over the seceding of the Eastern Region. That last sentence is also at odds with Achebe’s notion that Chick was, at heart, a Northerner.]

His closing words to me in that letter were

Let me hope to hear from you soon. Good-bye.

Yours truly,

Chick.

They turned out to be the last words I would ever hear from him.

Chick was killed in a fire fight on the night of July 29, 1967 near the University of Nigeria, Nsukka campus. For some weeks prior to that night, he would gather troops for ad hoc guerilla raids against the federal army moving about in the area. On this particular night, he was using an old Bedford truck sided with iron plates and equipped with artillery guns. Two differing stories of his death are told: one, that the jerry-built “tank” in which he rode was blown up by a new and powerful gun the federal troops had recently acquired; and the second, that in the midst of battle, he rose up out of the vehicle, shouted that he was Nzeogwu and that they should stop shooting; they did not. After the battle, Chick’s body was found inside the wrecked vehicle along with two others.

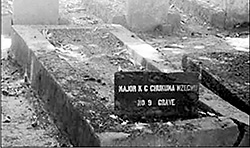

Chick’s grave at the military cemetery in Kaduna.

The government of Major General Yakubu Gowan, in a show of some courage, ordered Chick’s body to be taken to Kaduna and there to be buried in the military cemetery with full honors accorded him.

I think these words with which he closed his first letter to Sister Liam make a fitting epitaph:

Finally, let me thank you for your kindness in writing on such a fine picture card.It is very sat- isfying gazing thoughtfully at the five birds gracefully sailing over the beautiful landscape and one cannot help feeling that our flight from yesterday’s gloom will similarly end in eternal bliss. Farewell.

Yours in Jesus Christ.

Olusegun Obasanjo’s biography Nzeogwu does little to flesh out this man’s character. I think his innocence matched our own as Peace Corps Volunteers in the belief that we had found a way to make a better world . . . each of us pitching in to the best of our abilities wherever they were needed. He was inspired by the Vol- unteers he met. We talked once about what a nation must be like to have the creativity and the funds and the will to initiate and promote such a program. He repeatedly shook his head in wonderment at the notion of a nation-state sending legions of young people, without experience, and, frankly, amateurs (That was a word we argued over with him insisting he didn’t mean non-professional, but rather “for the love of it.”) off into the beyond and picking up the cost of it. It was this essence of how Americans governed themselves, with motives beyond greed or gain, that I believe was tucked into a corner of his reasoning process when he suited up for the events of January 15, 1966.

Olusegun Obasanjo’s biography Nzeogwu does little to flesh out this man’s character. I think his innocence matched our own as Peace Corps Volunteers in the belief that we had found a way to make a better world . . . each of us pitching in to the best of our abilities wherever they were needed. He was inspired by the Vol- unteers he met. We talked once about what a nation must be like to have the creativity and the funds and the will to initiate and promote such a program. He repeatedly shook his head in wonderment at the notion of a nation-state sending legions of young people, without experience, and, frankly, amateurs (That was a word we argued over with him insisting he didn’t mean non-professional, but rather “for the love of it.”) off into the beyond and picking up the cost of it. It was this essence of how Americans governed themselves, with motives beyond greed or gain, that I believe was tucked into a corner of his reasoning process when he suited up for the events of January 15, 1966.

How the historians will treat Chickwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu remains to be seen. A new generation of Nigerian scholars is emerging who study their country’s narrative with a keen eye. Perhaps enough time has elapsed for them to untangle the convoluted path their nation took from that ancient time in the ’60s to the present day. Perhaps they can determine, now, who were the heroes and who were not. And who Nzeogwu really was. What I do know, beyond any doubt, is that Chick had a unique gift for friendship and a deep abiding love for his country. And I would be pleased to contribute that certainty to their efforts.

•

*A note of irony: While researching for this article, I found one of Chick’s letters tucked into my signed copy of Sir Ahmadu Bello’s autobiography, My Life.

**I personally saw an example of the Sardauna’s corruption, or at least his extravagance at Leventis Motors, where I had my motorcycle repaired: the Greek foreman at Leventis let me sit, prior to delivery, in the new custom-built gold Rolls Royce the premier had ordered with extra seats for his wives. It had a drinks bar! (for serving Fanta, no doubt!)

Tim (L) with the late Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, former president of Notre Dame University and his longtime friend and mentor.

•

First published in the Friends of Nigeria Newletter, Summer 2015, Vol 19, No 4 (published with permission)

Thank you, Tim Carroll, for your service in Nigeria. Thank you for writing and sharing this. Marian, thank you for publishing. This is a powerful historic document. I hope so much that it has also been included with the Friends of Nigeria archive at American University’s Peace Corps Community Archive. Words can not express how powerful I found this.

In this piece Tim Carroll wrote a memorable memoir of those times and beautifully framed his striking friendship with a fine young man. I loved his horse tales. But as a Nigeria IV 1962-64 PCV who lived through much of this turmoil and witnessed the lead-up to the Biafran War, I knew that our own government was dangerously wrong promoting Nigeria as Africa’s “showcase for democracy.” Eh! EH! Many of us knew, early on, that a bad civil war was in the offing and that the weak colonial construct called Nigeria and its people would suffer deeply. I even argued this point with the American consul in Ibadan to the point that he asked me to leave his office. And here is what that 1966 coup immediately accomplished:

“When the coup was over, 11 senior Nigerian politicians and two soldiers lay dead and three others were kidnapped. News sources confirmed that Bello’s assassination was one part of a carefully coordinated attack planned and carried out by Nzeogwu and some of his fellow army officers. . . .”

Beyond that make-or-break attack, in this piece I was more struck by this comment by the Major, followed by Tim’s explanation: “I won’t bore you with any more details but you can take it from me that the figures often reported are an understatement. Casualty figures may be in excess of half a million. [He is referencing the merciless Hausa attacks on Igbo’s throughout the North during this period.] In spite of that, I am not discouraged. . . . I think his innocence matched our own as Peace Corps Volunteers in the belief that we had found a way to make a better world . . . each of us pitching in to the best of our abilities wherever they were needed.”

Well, looking back it seems to me that Tim’s referencing of his friend’s “innocence” doesn’t attend to the fact that the young major was less than innocent, he was deeply and dangerously immature, callow. His tiny corps of young officers who undertook this coup, which in any case, was bound to fail, caused the deaths of “in excess of half a million” real innocents? When a young Christian from the Middle Belt decides to murder Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sardauna of Sokoto, Premier of the Northern Region of Nigeria, isn’t it incumbent upon him to look downstream to anticipate a reaction? While the attack itself may have been “carefully coordinated,” not a jot or iota of strategic planning, much less wisdom accompanied those young men on their night of killings. Things only got worse. Better had they stood in bed, kept to their barracks. Major Nzeogwu had been an idiot.

Given the decades that have passed since then, I welcome corrections to this analysis.

I would like to add the comment that the good Major in his letter never expressed remorse, much less guilt for directly initiating the death of half a million fellow countrymen. That strikes me as a total blindness to one’s actions worthy of a Dostoyevsky novel….

You are not a Nigerian so don’t speak for Nigerians …it’s people like u that joins hands wit our government make life hard and by the way what do you know about the millions you said that die….i too know go kill u one day.

Thank you. Till date, his kinsmen never felt any reason to feel sorry for the actions of Nzeogwu. People like Achebe even alluded that he was more Hausa than Igbo and hence they feel no responsibility.

But Nigerians hold all sorts of views on the issues, so how can you, (John?) Kerry, speak for all of us on the matter?

Are you one of the criminal minded “Europeans” (euphemism for CIA/M15 operatives) who directed the massacring of Igbo civilians in 1967 through 1970? You seem not satisfied with the genocide you perpetrated against the Igbos, so you are continuing it through your callous language and remorselessness. The very vice that Nzeogwu and his colleagues tried to eradicate (personality cult that overshadowed nationalism) was what you are, over 50 years later, asserting that they should have taken into consideration before carrying out their mission? In your genocidal mind, whatever shortcoming you deem worthy of attributing to Nzeogwu justifies the mass murdering of over a half a million Igbos, mostly civilians and children, who had nothing to do with politics? Are you related to Hitler, if you don’t mind me asking?

Your argument is illogical, for it is the same argument of the coldblooded white men who directed and justified the atrocities visited on Igbos and Biafrans. Tim’s references to innocence was not an absolution of blame, it was to the naivety of Nzeogwu and his colleagues in assuming that they were equipped enough to unmake what British imperialism had made. Nigerians are still living and dying under that British’s cage.

You are as sick as Nzeogwu was. No remorse for the action. I cannot feel any remorse for the reaction. Just like the US felt no remorse for Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

My sentiments exactly! The cure the coupists brought was way worse than the ills they supposedly wanted to remedy

Your last comment was in the extreme – for referring to Major Nzeogwu as an idiot. He, alongside his comrades were driven by patriotism, except that they allowed their youthful zest to take a greater chunk of their thinking plan. Remember, it’s Africa and African politicians we are talking about here.. Corruption is in their blood which I think, Mr Tim had a sneak peek of the opulent lifestyle of Mr Premier, the Sardauna himself at the Leventis Store, which he lived at the expense of the populace. That’s the only way such can be removed.

I love Nzeogwu and live by his fine reputation and character. I was amazed to have seen his handwriting. Thank you caroll

Please I will love to kw if I could get copies of other letters major nzeogwu wrote to him…just like that of the one he wrote to sis Liam. .

Hello,

Would you by any chance happen to have any copies of pictures of “Chick” , besides the only ones seen online?

Tim Herbert’s conclusion in his comments of May 3 2016 and his addendum of May 4 2016 says it all precisely and honestly, albeit there was a slight error when he referred to Nzeogwu as someone from the Middle-Belt. The actions of the coup plotters of January 15 1966 led to the terrible repercussions that should have been apprehended. Nzeogwu was no doubt a patriot. But the consequences of the actions he took with his collaborators was inevitable. It set Nigeria back 50 years at least. And the outcomes are still affecting us till date. Until all of Nigerians realize and admit that the coup of January 1966 was unwarranted, we will still be living in deceit as our generation and subsequent ones will not easily reconcile.

Nzeogwu was a patriot. He and his colleagues wanted a better Nigeria that will be free of corrupt politicians. Their strategy was to eliminate corrupt politicians across the country. There was however a snag. Amongst the five majors those saddled with the responsibility to execute the coup in the south bungled it. They failed to faithfully execute the coup as planned. They failed to kill Igbo politicians and army officers either because they became lilly-livered to kill their own or that they had no intention of killing their own in the first place. This was a tragic mistake that led to the loss of at least one million lives.

That tragic mistake has been widely interpreted. Some say that there was a coup within the coup as the real leader of the coup, Emma Ifeajuna had a secret agenda different from that commonly agreed to by him and his colleagues. It is alleged that Ifeajuna had misguided considerations different from the patriotic considerations of his colleagues and used his colleagues to execute his secret agenda. Some say that Ifeajuna and his colleagues in the south were inept or incompetent, which was why only one Igbo was killed in the south. Ifeajuna himself in an interview in 1967 accused his colleagues of bungling the coup in the south for misguided reasons. Whatever is the case, the suspicion of ulterior motives led to reprisals and eventually the civil war. Nzeogwu patriotically played his role as agreed by the group. His colleagues let him down.

There was no plan to kill corrupt Igbo leaders. It was a grand design to exterminate the North. Nzeogwu was a patriot indeed.

You’re blinded by your rage and narrow-mindedness such that you cannot see the truth even though it’s sitting heavy on your nose! It takes a level of intelligence to see why the coup failed and while despite gis actions, he remains blameless because his intentions were obviously honest. Unfortunately, you do not possess that level of intelligence.

I’ll leave the last word on this to a Northern officer, Domkat Bali who referred to Nzeogwu as “a nice, charismatic and disciplined officer, highly admired and respected by his colleagues. He was not in the habit of being found in the company of women all the time messing about with them in the officers mess, a pastime of many young officers then. We believed that he was a genuine patriotic officer who organised the 1966 coup with the best of intentions who was let down by his collaborators. “If we had captured him alive, he would not have been killed. I believe he probably would have been tried for his role in the January 15 coup, jailed and probably freed after some time. His death was regrettable.”

nzeogwu was not killed by nigerian soldiers but by biafran soldiers.

are you the Biafran soldier that shot him?

His death still remains a mystery.

This is a rational inference many people, including me, have drawn. Obasanjo’s observation that no attempt was made by the Biafran side to retrieve his body days after he’d died and Ojukwu’s attitude and intolerance of any significant personality in the South East lend credence to this conclusion.

“Tijanni Katsina”, a name never mentioned, a person prior to this lost to history; imprisoned in Jan 66 for complicity in the Coup, very interesting

A profound account from an independent and candid observer.

What Nzeogwu and his bunch tried to remove in the ’66 coup is still apparent today. Corruption is an endemic affliction that has been difficult to deal with.

Just last week, February 23, 2019, Nigerians voted for Honesty rather than Corruption, in the two prominent candidates out of the 70+ candidates that contested the election.

I saw some folks condemning Nzeogwu, what about Ojukwu who mislead his people?

If There Was A Country, is any reference to go by, the civil war was needless and avoidable.

Those beating the drums of war again ought to have learned from history, but unfortunately, people hardly learn.

of course blame the victims and leave out Gowon, the british, muritala, buhari, ibb, obj and the rest of them who were doing killings from 1950 to this day

Nzeogwu was a great Nigerian patriot erroneously referred to as coup plotter!

What about Murtala, Buhari, Babangida & devilish Abacha? Were they not coup plotters? Only that they were successful coup plotters.

But none of them comes close to Nzeogwu’s disposition: Politically and socially. His understanding of political intrigues was too far ahead of his time let alone his ‘Inaugural coup’ speech. At only 29yrs old crafting such a speech that captured true reflections during that error is beyond my understanding. The useless four of them had to wait to rise to Major General or full General like Abacha before summoning the courage to mount a coup. Three of them never even participated in the actual coups, they had to be flown in only to take over: Murtala from London, Buhari from Jos, IBB from Minna. Only Abacha did it himself albeit as s full General against a civilian Shonekan Ernest.

Ironse unpreparedly scuttled Nzeogwu’s plans. From all his writings & interviews Nzeogwu was well grounded to take over while Ironse was inept for the job. At that stage of the coup where Prime Minister, two Regional Premiers, two Brigadiers, two Colonels & many more were executed the coup had ostensibly succeeded the honorable thing any general would do was to let go. Ironse’s selfishness led to him ultimately being annihilated in a battle he never initiated. No apologies for his ghastly assassination.

What was so difficult for a Major to take over? A Major is a very senior military position or rightly the very middle position. In some countries Captains or mere lieutenants have ruled what more a Major?

Nzeogwu was a major by position only but in reality he was a General, more politically astute especially for his age. Analysis of his letters, speeches & interviews leads me to believe he may have been used by those in high echelons of power: his views were too mature for a 29yr! Tim Carroll may have been an accomplice behind the nature Inaugural speech.

On second thought Nzeogwu himself was well spoken: eloquent, articulate, charismatic, astute. You have to give it to Nzeogwu. Nigerian’s best President that never was!

[by LufSm, an Africanist from Central Africa]

Typo errors:

Kindly replace ‘error’ with ‘era’ , ‘nature’ with ‘mature’

What is this rambling?

Thank you Sir.

Please a mistake, it was Nzeogwu not Ifeajuna that accused his colleagues of misguided consideration…………

Thank you for sharing. Tim. There is so little young Nigerians know about “Chick” except that he was a coup plotter. As a young Nigerian with a keen eye for history, your account of your friendship with him and these letters have helped to put the man he was into perspective.

Nigeria, described by an American social commentator as”Fantastically corrupt” had had the bug since the Colonial era.

The Colonists aided and abetted corruption, something that is abhorred in their motherland, so far it ultimately benefited their interests.

The crop of politicians they handed power to then took corruption to a whole new level and entrenched it as the norm.

Needless to say therefore that Nzeogwu and his fellow coup plotters did not fully understand that they were dealing with a hydra-headed monster that cannot be placated by eliminating a few politicians.

K. C,

Lagos.

Hi Tim,

Thanks for this piece, What is the name of the catholic church that Nzeogwu attended in Kaduna?

Nzeogwu was a “Major in the Nigerian Army, a militant rebel, a Roman Catholic and a romantic…a difficult but fascinating fusion.”

But Nzeogwu’s attributes are not merely “difficult” but an impossible fusion: and it showed in the apocalyptic calamity that the coup triggered, which still reverberates across the country today. The Igbo have not fully recovered from the physical, economic, political and emotional consequences of his One Nigeria” fantasy.

Unfortunately, in spite of his high intelligence, encyclopedic knowledge and incredible talents, Nzeogwu was very “naive.” He failed to understand that:

1) It was Never the intention of Britain to allow Nigeria to be a fully sovereign and independent country.

2) Britain’s determination to continue to rule Nigeria “indirectly” became stronger with the discovery of huge petroleum reserves, including the largest gas reserves in Africa.

3) Since most of Nigeria’s oil/gas riches are located in the Igbo-speaking areas of the country, among Nzeogwu’s people, Britain would Never allow an Igbo, a people they hate with a passion, to rule Nigeria-no matter how “de-tribalized” and pan-Nigeria one is.

4) British colonial officials had chosen the Muslim Fulani/Hausa as their sub-colonial agents and given them needed arms and diplomatic support to brutally maintain their “one Nigeria” fantasy and to keep the oil/gas flowing.

5) As recently declassified State Department documents on Nigeria have shown, it was Britain (dragging the US along) that indeed axed the Aburi Accord and virtually “forced” Nigeria to attack Biafra in order to seize and control its oil/gas riches worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

6) Given its abnormal geo-political structure, ethnic/linguistic differences and the endemic and violent Christian-Muslim divide, it is virtually “impossible” for anyone to govern Nigeria democratically except to rule it with brutal force. Even God-come-down-earth as a human being cannot govern the “potemkin” State.

Firstly, I would like to thank you, Tim, for writing this piece and for providing a scanned copy of Chukwuma’s letter. I must say, I felt a sort of “fan boy” rush seeing his handwriting.

Secondly, Chukwuma, as well as many great minded Africans have had their vision and light snuffed out by what he correctly described as “reactionaries” AKA stooges of the British neo-colonialists.

All I can say now is, Rest on Brother Nzeogwu. You have fought your fight, Nwannem. We that have the gift of life now, will continue it.

Igbos should take a significant share of the for whatever befell Nigeria not the British. If Ifeajuna and Ben Gbulie had carried out their assignment as they were required, this entire British narrative would’ve been non-existent. Nigeria paid a price not because the British wanted to maintain a grip on the country but because of the actions and inactions of a group within the initial ’66 coup, Ironsi’s subsequent actions and Ojukwu’s lack of tact and failure to listen to anyone’s advise but himself. Point the finger where you want but look at the four fingers pointing back at you!