The Legendary PCV Post Card

Marjorie Mitchelmore was a twenty-three-year-old magna cum laude graduate of Smith College when she became one of the first people to apply in 1961 to the new Peace Corps. She was attractive, funny, and a smart woman and was selected to go to Nigeria.

After seven weeks of training at Harvard, her group flew to Nigeria. There Marjorie and the other Trainees were to complete the second phase of their teacher training at University College at Ibadan, fifty miles north of Lagos, the capital of Nigeria. By all accounts, she was an outstanding Trainee.

Then on the evening of October 13, 1961, she wrote a postcard to her boyfriend in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Here is what she had to say:

Dear Bobbo: Don’t be furious at getting a postcard. I promise a letter next time. I wanted you to see the incredible and fascinating city we were in. With all the training we had, we really were not prepared for the squalor and absolutely primitive living conditions rampant both in the city and in the bush. We had no ideas what “underdeveloped” meant. It really is a revelation and after we got over the initial horrified shock, a very rewarding experience. Everyone except us lives on the streets, cooks in the streets, sells in the streets, and even goes to the bathroom in the street. Please write. Marge.

P.S. We are excessively cut off from the rest of the world.

The postcard never was mailed. It is said that it was found on the grounds of University College at Ibadan near Marjorie’s dormitory, Queen Elizabeth Hall. The finder was a Nigerian student at the college. Copies of the postcard were made and distributed. Volunteers were immediately denounced as “agents of imperialism” and “members of America’s international spy ring.”

The protest made front-page news in Nigeria and sparked an international incident. As the Nigerian Ambassador to the United States said at the time, “No one likes to be called primitive.”

Murrey Frank

In the middle of this “international incident” was Murray Frank, the thirty-four-year-old Western Regional Director of the Peace Corps in Nigeria. He had only arrived in-country a few weeks before the Trainees and was developing teaching assignments for the first Volunteers when the infamous postcard was found.

In the Fall, 1999 issue of the Friends of Nigeria Newsletter, Murray Frank recalls the incident and those early tense days in Ibadan, Nigeria. Murray writes:

“The Postcard Affair began October 14, 1961. That was the day Peace Corps Nigeria almost came to an end . . . before it started. And I was in the middle of it all.

“Nigeria I had arrived in Ibadan early in October. Volunteers were settling into dormitories at the University of Ibadan (then a part of the University of London and called University College of Ibadan) where they would continue the training started at Harvard.

“I was the Western Region Peace Corps Representative. My family and I arrived in September, ahead of any other Regional Representatives and their families. Brent Ashabranner, who left AID to become Nigeria’s first Peace Corps Director, helped us get settled. We had a house in Bodija, a middle-class development between the center of Ibandan and the University. Residents included professionals and senior government officials – not quite the Peace Corps mold – but quite a comfortable area for a family with children aged two and four.

“I had nothing to do with Volunteer training. My job was to arrange Volunteer assignments. I would visit a potential location, meet the principal and staff, establish that there was a position for the Volunteer to fill, and check out living conditions. I had not gotten very far by Friday, October 13. However, I was getting to know Volunteers as work assignments were developing.

“Volunteers went to class and studied Monday through Saturday mornings. Friday night, October 13, PCV Marjorie Michelmore wrote a few letters and picture postcards and sent them to folks back home. She mailed them on the way to class Saturday morning. One of the postcards described her first impressions.

“When Volunteers arrived at dormitory dining halls for lunch Saturday, October 14, there was a copy, word for word, of that postcard at each place. Marjorie’s comments described how the average Nigerian lived. While not inaccurate, her comments were not flattering, and to a Nigerian student – especially one concerned about Western imperialism – the comments seemed downright insulting.

“A couple of Volunteers hitched a ride from the university to bring me the news. Protests were beginning on campus, Volunteers were being ostracized. This was clearly not a training issue. Now, I was in charge, God help me!

“I arranged for all of the Volunteers to come to my house while I went to the USIS library to phone Lagos. I didn’t have a phone. I told Ashabranner what I knew. He cabled Peace Corps Washington.

“By coincidence, the second-in-command at the American Embassy, the Deputy Chief of Mission, was on his way back to Lagos after a trip up North when the story broke. I met him at a local rest house with Marjorie and we agreed that she should go with him to Lagos. There was an AP stringer at the rest house. He could see that something was up.

“I went home to meet with Nigeria I Volunteers. I was totally unprepared for this.

“Initially the group felt anger – at Marjorie for getting us into this, at the Nigerians for making such a big deal out of one person’s comments on a postcard and holding all of them responsible.

“Should we issue a statement disassociating ourselves? If so, to whom? How? We got by that quickly and went on to examine how representative these students and their feelings were of the country, and especially of the people with whom we would be working

“Nigeria was newly independent but, in retrospect, I don’t know if we fully absorbed how deeply this influenced the students’ behavior. It had not been very long since independence had been won. The visages of the colonial period were still all around, including and especially white people who symbolized a colonial past. A Nigerian self-image based on new freedom was developing. Nigerians, at least by this group of young intellectuals, demanded respect.

“I understood it better after I attended the inauguration ceremonies when the University College of Ibadan became the independent University of Ibadan. Nnamdi Azikiwe (Zeke), the father of independence, was the main attraction. When it was his turn to speak, the excitement – the electricity – in the crowd was palpable. A zzzZZZEKE cheer went wherever he did. They cheered and cried for him and for the event that reaffirmed independence. Zeke insisted that the University of Ibadan was “our” university, free of London’s influence and now part of Nigeria’s development. It was thrilling – the closest I ever came to such intense nationalism.

“But on October 14, 1961, most of us had just confronted this intense nationalism for the first time. All of us had experienced student protests in the States. But this was quite different. It was not really about a postcard. We knew there were those who opposed foreigners “invading” their country and those who would use this incident for their own purposes. Some feared that we would not really be able to help Nigerians if that was how we wrote home about them.

“We asked many questions. Do we have a choice, or have our chances of success been reduced significantly? Why try to stay where so many don’t want us? Shouldn’t we go somewhere else where we are invited and start fresh? Can we continue to live and train at the University where there is such hostility toward us?

“And then the counter arguments came. We know Nigeria needs teachers. We can teach. We are not imperialists, nor CIA agents, nor ugly Americans. We know who we are. We can make a difference.

“We were agitated but the discussion was mostly calm, always serious. It was hard work that afternoon. Consensus was a long time in coming. I saw my role as the discussion leader. These were the folks who would be on the firing line. They had to decide for themselves.

“We were all young. The oldest in that room was 34. We were newly transplanted to a very different culture, confronted with a situation for which none of us had any real preparation. But the Volunteers had spirit and maturity.

“We continued to try to answer many questions. What are we doing here? Should we leave, or stay and prove that we have something to give? After many hours we made a decision.

“We wanted to stay.”

Murray with his wife Ginna, and their children Peter and Lisa in Nigeria on their way to a ceremony to crown a chief.

Marjorie’s postcard appeared in all Nigerian newspapers the next day. The story was in the American press, too. There were no directives nor advice from Peace Corps Washington or our Embassy. Only one message came. It was from the State Department asking “Were there really over 256 words on one-half the side of the postcard?”

In coming days and weeks, Volunteers continued to take some meals and sleep in the dormitories, but they were always isolated. One of the Volunteers, Aubrey Brown, had training and experience in non-violent resistance. He told the Nigerian students in his dorm that he would not eat if he couldn’t eat with them.

After a while, the Nigerians saw Aubrey meant it. When they brought a dinner tray to his room, he refused it. Soon the Nigerians invited him to join them at meals. Other Volunteers and students did the same. A dialogue began between students and the Volunteers – more valuable than if the incident had not taken place.

The Nigerian-American Society, and organization of Nigerians trained in America, also came to our defense in meetings, through letters to the editor, and with friendship. I remember particularly H.A. Oluwasanmi, who taught agronomy at the University of Ibadan and later was Chancellor of the University of Ife. His support and advice on how to understand the situation was invaluable.

Richard Taiwo, an engineer in one of the Western Region ministries was a likeable, garrulous supporter, praising the Peace Corps everywhere. He and others organized a party for us at one of the very visible clubs in Ibadan. There was plenty of Star beer and lessons in Highlife.

Another outspoken and effective supporter was Tai Solarin, principal of the Mayflower School which he founded and named for our Mayflower. Had it not been for the support and advice from the Nigerian-American group, it would have been far more difficult to weather the storm. We might not have made it.

The Volunteers’ behavior after the tumult of the Postcard Affair was special. PCVs remained calm and were not retaliatory with Nigerians who taunted them. These young men and women balanced individuality and group allegiance, knowing that the issues were not personal. They remained reasonably self-confident and able to listen and learn.

One of the early staff of the Peace Corps that I spoke to about the post card incident was Warren Wiggins, then the Associate Director for the Office of Program Development and Operations, and later to be the Deputy Director. Wiggins told me that the staff in 1961 were waiting for something to happen overseas with the Volunteers. Too many young people were overseas, he said, and there “had to be” an incident of some kind. On the afternoon of October 15, 1961, they got their incident when word reached Washington about Marjorie Michelmore and her postcard.

Gathering at HQ on that October Sunday afternoon, the senior staff was initially worried about Marjorie’s life, as well as the lives of the other Volunteers. Wiggins also realized that “The Peace Corps could be thrown out at any moment. It could be the domino theory–first we’re kicked out of Nigeria, then out of Ghana, and so on. Anything was possible.” It would be the end of the Peace Corps before it had really started.

At first there were rumors. One was [it was incorrect] that the U.S. Ambassador in Lagos, Joseph Palmer, was trying to force Marjorie out of the country against her will. Then the Peace Corps heard from Marjorie herself. She cabled Sarge Shriver telling him that it would be best for the Peace Corps, and best for her, if she came home immediately. The word was cabled back to Africa from PC/HQ: get Michelmore out of the Nigeria.

Wiggins always said Shriver was calm and cool in such moments of crisis. You know, Hemingway’s grace under pressure. But the courtly, as I recall him, Tim Adams, who had just come to the Peace Corps from the San Francisco Examiner to be the new public information officer for the agency, when the story broke in the press, said there was, “panic in Shriver’s heart. There really was. That postcard had created a cause celebrate. It was temporarily the talk of the universe.”

Shriver, however, was determined to outsmart the press. He didn’t want them meeting Michelmore when she arrived in the U.S. after a long overnight flight from Africa. He was afraid of what she might say. And what would they ask her about the new Peace Corps? Were these young white American kids up to living in Africa? Anything was possible and it would all be bad for the Peace Corps.

Shriver came up with a plan: Michelmore would fly from Lagos to London, then fly directly to Bermuda, and onto San Juan, Puerto Rico, where she would join up with Trainees at the new Peace Corps Outward Bound camp. She would then “impart cultural sensitivity caveats to the Peace Corps trainees.”

Tom Mathews, deputy director of Public Information, was dispatched to Bermuda to pick up Michelmore when she arrived on the island and fly on with her to Puerto Rico. [Marjorie’s escort officer from Lagos was a guy named Dick Ware, a tall, good looking African American who was an AID official in Nigeria, and who was about to joined the Peace Corps Staff. He would make sure to keep Marjorie away from the press leaving Lagos and on the layover in London.] All bases were covered.

Then, two nights later–the night Marjorie and Dick Ware are flying across the Atlantic– shortly after 2 a.m. EST, Tim Adams, got an urgent call from Wiggins. Warren had heard from Tom Mathews in Bermuda. The island was socked in and Marjorie’s plane was being diverted to Idlewild in New York. Shriver, Wiggins said, wanted Tim to get to New York before her BOAC plane landed. Sarge Shriver wanted to make sure that the first Peace Corps ET, Marjorie Michelmore, was kept away from the American press.

Meanwhile back at Murray Frank’s home, the PCVs had assembled and were trying to understand the intense reaction of the Nigerians. Nigeria, newly independent, was surrounded, as Murray put it, “with the visages of the colonial period, including and especially white people who symbolized a colonial past.”

What had quickly emerged in Nigeria was a self-image based on their new freedom, especially among the young intellectuals. These students and others were asking: how could the Americans help us if they were writing letters home about them?

While many of the new PCVs had experienced student protests in the U.S. they were still unprepared for what was directed at them. Could they survive the postcard? They didn’t know. They began to ask themselves: why stay when so many students wanted them to leave?

Other PCVs said. “We know Nigeria needs teachers. We can teach. We are not imperialists, nor CIA agents, nor ugly Americans. We know who we are. We can make a difference.”

In the long afternoon and night of discussion, Murray Frank was the discussion leader, moving the Volunteers from one hard point to the next. These young people were on the firing line, Murray knew, and they had to decide themselves.

And they were all young. Murray was the oldest in the room, only 34. Also, they were all newly transplanted in a new country, confronted with a situation that they had no preparation for, but they had, Murray recalls, “spirit and maturity.”

They decided to stay. They decided to tough it out.

That decision by this group of “Kennedy Kids” made all the difference in their lives, and in fact, made all the difference in the future of the Peace Corps. If they had ‘cut and run,’ giving up at the first brush up against a hostile group of HCNs who did not know the reason these Americans were in Nigeria, it is a good chance that the fledgling Peace Corps would not have survived those few months of its existence.

The next day in Nigeria, the next day in America, Marjorie’s postcard appeared in every newspaper; it was reported on the radio, and it was seen on television. The whole world knew what had happened in Africa with this young Peace Corps Volunteer. Within days, former president Eisenhower would make a political speech in Madison Square Garden in which he said that the U.S. should send Peace Corps Volunteers to the moon since it was also an underdeveloped country and they could do less harm there.

Out in Ibadan, Murray and his Nigerian Volunteers waited for directives from Washington, waited from advice from the Peace Corps HQ. There was no cable traffic from D.C.

Finally, a telegram arrived. It was from the State Department in Washington, D.C. The cable asked only one question: “Were there really over 256 words on one side of the postcard?”

Don’t you just love the State Department?

Tim Adams arrived at Idlewild Airport to a terminal overwhelmed with press people carrying tape recorders, cameras, and microphones.

Michelmore and Ware were about to touch down on a BOAC flight and Adams saddled up to a group of reporters and asked innocently, “Who’s coming in?” Adams thought it might be Grace Kelly, then due back in the States. “It’s that Peace Corps girl,” someone said and Tim’s heart dropped.

Slipping away from the reporters, Adams pulled out his official government Peace Corps ID and got past the customs officials and when the BOAC flight landed pulled Marjorie and Dick Ware into an empty room. The reporters, however, could see them on the other side of Customs, see Tim frantically telephoning Shriver at the Peace Corps Headquarters. Tim asked what he should do. Shriver told him, “Tim, I don’t want the press talking to Michelmore.”

Adams told Shriver that there was no way Marjorie couldn’t talk to the reporters. When Shriver didn’t respond, Tim took it as an opportunity to hang up. With Marjorie and Dick Ware behind him, Adams went out to handle the press conference.

Grabbing a chair, he jumped up and told the swarming reporters that Miss Michelmore was very tired and that she would take only a few questions. Reporters were given five minutes. T.V. and radio got another five minutes. It worked. That night, ET Marjorie Michelmore was charming, attractive, and normal, and it was all over the next day’s papers and on the nightly news.

By now at Idlewild a half dozen more Peace Corps HQ people had arrived, all having been dispatched from D.C. These were some of the famous original staffers at the agency: Ruth Olson operated as crisis manager for the occasion. She was well versed for the job. She had come to the Peace Corps in the first week of the agency from years of working in the military during World War II; Betty Harris, a former journalist and political operative from Texas was on hand; Tom Matthews had just arrived back from Bermuda. And also arriving unannounced and unexpected, sneaking through the press of people, was Marjorie’s boyfriend from Boston, an NAACP lawyer.

It was here that Marjorie received her handwritten note from JFK. I don’t know how that was arranged, my guess it was done by Bill Moyers, the rising start of the next Johnson administration, and at age 27, the Associate Director for Public Affairs for the Peace Corps. Moyers would go onto becoming Shriver’s Deputy Director.

When the press cleared out, Tom Mathews headed back to Washington to brief Shriver on what had happened. Tim Adams and the others got tickets for the next flight to Puerto Rico.

There was, however, a new problem for the Peace Corps. Marjorie Michelmore didn’t want to go to the Peace Corps’ Outward Bound camp in Arecibo, Puerto Rico. She had heard–via the Peace Corps Volunteer network that Camp Arecibo was “all Tarzan”– and that wasn’t her style. Tim was back on the phone to Shriver in D.C.

At Idlewild Tim Adams, Ruth Olson and Betty Harris convince Margorie to go to Puerto Rico. Michelmore agreed to go for a ‘few days’ and Tim informed Shriver, telling Sarge he would keep in touch. He boarded the plane with Ruth Olson and Marjorie, thinking that once he was on the plane to Puerto Rico, he’ll be okay.

Tim was wrong.

On the plane, Adams recognized Carl Mydans. At the time Mydans was a famous photojournalist, one of the giants for Life Magazine. Adams thinks: this is not a coincidence. With Mydans was a beautiful young woman reporter, Marjorie Byers. They are in first class. Of course, this is Life Magazine.

When they are airborne, Carl walks back from first class to talk to Tim who is riding in coach. [Of course, he works for the Peace Corps.] “Carl is such a gentleman,” Tim says, “I finally relented and we were able to negotiate terms under which Mydans and Marjorie Byers could get an interview with Michelmore after we all arrived in Puerto Rico.”

When they arrived in San Juan they are met by Rafael Sancho-Bonet, then the Peace Corps’ overall administrator in Puerto Rico [later he would be the CD in Chile.] Rafael drives them all to meet William Sloane Coffin, the director of the camp. Coffin is famous, especially in his own mind, and had been a chaplain at Yale, later an antiwar spokesman, later still, the senior rector at Riverside Church in New York City. In the Peace Corps Coffin was well liked, and well hated.

That day he was pissed that Michelmore had been “foisted on him” by Shriver. He did not want her in his camp. [Of course, Marjorie didn’t want to be there either.]

Coffin position was, “I want it made clear that this girl is going to be treated just like everybody else here. Up before dawn, rappel down the dam, do drown proofing, conquer the obstacle course, etcetera.”

Marjorie wasn’t going to have any of it. “I will do this for a couple days to accommodate the Peace Corps,” she tells all of them, “but I view it as an unnecessarily punitive action, and there is a limit. If I am not permitted to leave very, very soon, I will leave on my own.”

“Marjorie wasn’t kidding,” recalled Adams. “She was ladylike, but tough. And she just wasn’t going to take any shit from Coffin.”

Something had to be done, and it was, by Ruth Olson, Rafael Sancho-Bonet, and Tim Adams. They would handle this ‘incident’ for the Peace Corps. They got Michelmore, to use early Peace Corps terminology, ‘in, up, and out’ of Arecibo within two days.

Meanwhile back in Nigeria, another part of the “preposterous postcard incident” as Tim Adams termed it, was taking place. In Ibadan, between the PCVs and Nigerian students, there were real problems.

Segments of the U.S. Press were all over the postcard incident. The U.S. News and World Report wrote, “From the moment of its inception, despite laudable aims, the Peace Corps was bound to run into trouble.” They condemned the naivete of the entire concept and claimed, “this is only the first big storm.”

Commonweal wrote in an editorial “The problem involved is really bigger than the Peace Corps for it reflects the gap that exists between the wealthy U.S. and most of the rest of the world. Given this fact, incidents like the postcard affair are bound to happen.”

Former President Eisenhower added his two cents, saying the “postcard” was evidence of the worthlessness of Kennedy’s new idea.

However, columnist James Weschsler of the New York Post came to the aid of the Peace Corps and Marjorie. “Nothing in the card was sinister. It contained the instinctive expression of horror of an affluent American girl in her first direct encounter with the gruesome squalor of Nigeria. She was neither patronizing nor self-righteous in her comment; yet, whoever found the lost card managed to stage a big production.”

Michelmore, meanwhile, was getting support from Nigerians writing letters to Nigerian newspapers. Tai Solarin in the Lagos Daily Times wrote, “not a single Nigerian who knew this part of Nigeria would suggest that she was sending home a make-up story.”

While Murray Frank and the PCVs at University College of Ibadan might not have known it at first, the Volunteers were also getting help from Washington. Shriver met with the President as soon as the news broke, telegrams were going back and forth between the Peace Corps and Sam Proctor, the Peace Corps Director in Nigeria, on how to handle the situation.

And Marjorie, too, was well aware of what was happening around her because of the postcard. She would later write Kennedy, “I regret very much my part in the unfortunate affair at Ibadan. I hope that the embarrassment is caused the country and the peace corps effort will be neither serious nor lasting.

Marjorie was right. Five months after the postcard incident the second group of Volunteers arrived in Nigeria and were met at the airport by Prime Minister Abubakar Belewwa.

Nigerian PCV Aubrey Brown, who had had training and experience in non-violence resistance in the late fifties, led the Volunteers, and the Nigerian students, out of this confrontation over the postcard by the end of October 1961. The PCVs had continued to take some meals and sleep in the dormitories, but they were isolated and shunned by the Nigerian students. Then Aubrey told the Nigerian students in his dorm that he would not eat if they would not eat with him.

The Nigerians began to bring him dinner trays to his room but he refused to eat. And soon they invited him to join them at meals. Other Volunteers and students did the same. Slowly, a dialogue began between the students and the Volunteers, which was, as Murray recalls, “more valuable than if the incident had not taken place.”

Other Nigerians came to the help of the PCVs. The Nigerian-American Society, an organization of Nigerians trained in America, wrote letters to the editors of newspapers. One man, H.A. Oluwasanmi, who taught agronomy at the University of Ibadan and later was Chancellor the University of Ife, gave not only support to the Volunteers and Murray Frank, but his advice on how to understand the situation was, in Murray’s word, “invaluable.”

Richard Taiwo, an engineer in one of the Western Region ministries and a warm and wonderful man and supporter of the Peace Corps, praised the Volunteers and organized with others a party for all the PCVs at a very visible club in Ibadan, where there was plenty of Star beer and lessons in Highlife.

The Peace Corps in Nigeria also got help from Tai Solarin, principal of the Mayflower School, which he founded and named for our Mayflower, who came to the side of the Volunteers. If it wasn’t for these men, and the Nigerian-American group, Murray Franks now believes, “We might not have made it.”

In the aftermath of the incident, Murray would write, “PCVs remained calm and were not retaliatory with Nigerians who taunted them. These young men and women balanced individuality and group allegiance, knowing that the issues were not personal. They remained reasonably self-confident and able to listen and learn.”

The first real crisis of the Peace Corps and on-the-job training of what it meant to be a PCV had been averted and the infamous postcard turned into a moment of understanding and acceptance by all. The “Kennedy Kids” had shown their detractors in the United States that they weren’t kids. And as Murray Frank, who guided them successfully through all these first months in Africa, summed up years later, “I would hope that if any new PCVs go to Nigeria they will be as good as the Nigeria I Volunteers. They couldn’t be better.”

In 1965 Bob Gale, then running the Peace Corps Recruitment Office, traveled out to Ibadan, Nigeria, for a COS Conference. Gale had been a vice president at Carlton College and had developed the famous Peace Corps recruitment blitz [the most famous of all was the first in early October 1963 when teams of recruiters hit college campuses; these were mostly non-RPCVs as the first PCVs were just arriving back in the States. These all-out assaults on college campuses were very successful at recruiting Trainees. These early blitz teams were replaced by ’67 with teams of RPCVs working out of regional offices, and HQ non-PCV staff rarely traveled outside of Washington to recruit Volunteers.]

Back in Nigeria, Gale arrived late in Ibadan from Washington and met up with a Nigeria APCD and headed for a local bar where he was the only white man having a drink. Then in walked another huge white American kid and a smaller African. Gale recognized the American. He had recently been the co-captain of the Carlton College football team when Gale was there, and was a PCV in Ghana. He was hitchhiking through Nigeria and had been picked up by this Nigerian who, when learning his rider was a Peace Corps Volunteer, immediately told him that he was the person who had discovered the famous postcard of October 1961, four years earlier.

The Nigerian explained that he was then working at the post office in Ibadan and had been told by a group of left-wing students at the University to look for any postcards from PCVs that might discredit the Peace Corps.

In her book, Come As You Are Coates Redmon asked an RPCV from Nigeria about the claim and the RPCV replied that “We’ve heard stories and stories. I think that no one knows the whole truth. But one thing is certain. Peace Corps Volunteers in Nigeria never send postcards. They are haunted.”

One Last Post Card

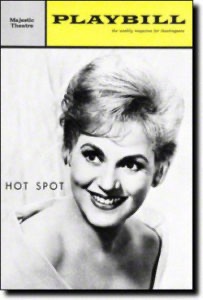

The “Peace Corps Postcard” had one more act to play. What happened to Marjorie Michelmore inspired a Broadway musical, Hot Spot. It starred Judy Holliday in her last Broadway show. Premiering on April 19, 1963 at the Majestic Theater in New York, the play closed after only 43 performances and 5 previews, gaining the honor of being one of Broadway’s most famous flops.

The “Peace Corps Postcard” had one more act to play. What happened to Marjorie Michelmore inspired a Broadway musical, Hot Spot. It starred Judy Holliday in her last Broadway show. Premiering on April 19, 1963 at the Majestic Theater in New York, the play closed after only 43 performances and 5 previews, gaining the honor of being one of Broadway’s most famous flops.

What was the play about, you’d ask? Well, it was about a Peace Corps Volunteer, a hygiene teacher “Sally Hopwinder” who is stationed in a fictional nation, “D’hum.” PCV Hopwinder concocts a plan to obtain U.S. aid for D’hum by convincing the Pentagon that Russia is about to invade it. It was generally accepted that this political satire was inspired by the furor over the Michelmore postcard. “The New York Times drama critic wrote, “a Peace Corps girl with a warm heart and a knack for getting herself and her country into trouble.”

According to Steven Suskin, The New York theater critic, “it was one of those big-budget, big-advance-sale bonanzas which go wrong and turn into highly public busts.” In a review in Billboard, “Predictions of failure proceeded the show and these were confirmed when the New York Critics Circle passed a unanimous negative judgment.”

In his book, When The World Calls: The Inside Story of the Peace Corps and its First Fifty Years, Stanley Meisler writes, “Since the role was played by the delightful Judy Holliday, the Peace Corps could hardly complain about the attention.”

And so our story ends and the curtain comes down on the famous postcard incident. We all know, and we all remember, the postcards and letters that we sent home and what we wrote in those postcards and letters. What happened to young and innocent Marjorie Michelmore in Nigeria could have happened to almost anyone in the Peace Corps.

So, to everyone serving overseas today remember what JFK said on the White House lawn when he nodded goodbye to us, slipped his hand into his jacket pocket, and then, almost as an afterthought, said, “But no post cards.”

John Coyne (Ethiopia 1962-64)

Whatever happened to Marjorie Michelmore after she returned and when on with her life. Was any follow-up about her even done?

I made contact with her in the mid-90s. She didn’t want to be interviewed and she had moved on successfully with her life. A few years back I heard that she had passed away.

John,

An excellent replay of the old adage: what didn’t break us only made us stronger.

Well spoken Young Jerry. I went through a similar experience (I wasn’t the protagonist) at my site in Colombia. I won’t recount it but it demonstratively had potential for another black eye for the Peace Corps.

John,

You are not only a brilliant raconteur

but a living – walking Peace Corps encyclopedia.

We have all heard of this postcard incident

but for most of us not in this extensive detail.

How fortunate that those involved had such

strong humanitarian values and character

so that everyone gained such deep cross cultural understanding on both sides of the Atlantic – that,

no doubt, permeated the rest of their lives.

Hopefully, you’re writing the definitive

historical tome on the Peace Corps?

Your Peace Corps knowledge and dedication

know no bounds.

Sending much appreciation,

Geri Critchley, Senegal 71/72

PS John – With ALL your writing about the Peace Corps, you’ve already written your tome.

I’ll just keep reading peacecorpsworldwide.com

past and present

Thank you, Geri. The real value of ‘stories told by RPCVs’ is that they are making the contribution. It is the tales told to their children and friends that matter the most. That is why Marian and I started our newsletter some 34 years ago, and what is now our website. It’s the Third Goal of the Peace Corps.

: – ) Thank you.

Hi Geri: Good to read your comments. And John does a terrific job. He threatened to retire a couple of years ago, but I think the Board revised his pay and bonus schedule so he decided to continue.

Or something…

Cheers,

Jim

so good to hear from you. Hope all is well. I moved to Palo Alro – love it -(new grandmother.)

health & peace

John…that was such a famous incident, glad you filled us in on it. And I had the same question as posted above, what happened to her. I was not surprised she didn’t want to talk about it. I was also struck by how much PC leadership wanted to keep her away from the ‘press’ at the time. If it happened today, she could just take a tip from Fox News and say ‘what postcard, I have just been traveling in Norway’.

cheers,

Jim