The Gringo I Knew by Rich Wandschneider (Turkey)

by Rich Wandschneider (Turkey 1965-67)

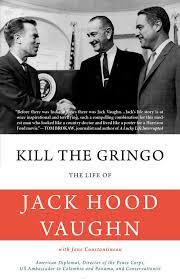

Jack Hood Vaughn’s autobiography, Kill the Gringo, came to me from Leif Christoffersen, who had served with Jack on the board of trustees of Earth University in Costa Rica. Leif knew I had been in the Peace Corps a long time ago, and wondered whether I knew Jack.

Leif, like Jack, is my elder, and like Jack, had worked in international development around the world, and their paths happened to cross in Costa Rica, and they liked each other. Leif’s mostly retired now, and comes to visit a son who lives here, and then he’s off to natal Norway, his home in Virginia, or a board meeting or consultation somewhere else. He always calls me for coffee or lunch. I think he’s fascinated that I was in the Peace Corps and on staff a long time ago, and seemed to have wrapped up my international experience in those five years, and then come to this rural Oregon place and settle — for fifty years and counting.

When I told him that I had spent a year in Washington D.C. as a Peace Corps Fellow and that our group of 19 sometimes met with Jack, and sometimes sat in on meetings with country directors. He said I should read the book. And before he left town, I had my own copy.

The first chapter is headed “1966-1969,” the time that Jack Vaughn followed Sarge Shriver and served as the second Director of the Peace Corps.

The first chapter is headed “1966-1969,” the time that Jack Vaughn followed Sarge Shriver and served as the second Director of the Peace Corps.

The book’s title comes from Jack’s career as a boxer, which begins in chapter two. Boxing begins when Jack’s dad hangs a pair of miniature gloves at the crib, gets serious when he is in high school and fights amateur and Golden Gloves, and follows him to college, where he coaches the U of Michigan boxing team as a college senior—and graduates with a degree in French! In order to get the coaching job, Jack needed pro experience beyond his Golden Glove and low-paying “amateur” bouts, and his mentor sent him to Mexico for a few quick pro matches; that was the first but not the last time that someone tried to “kill the gringo.”

Boxing and languages weave in and out of the book as do war and peace. Featherweight Jack gets on his D.I.’s good side in Marine Corps boot camp with an impromptu KO of a 190-pound football hero and climbs up to 130 pounds as he heads to Guadalcanal, Guam, and Okinawa. He studies Japanese and Chinese amidst the battles, gets an award for interrogating Japanese prisoners, and then is headed for a landing on Japan’s mainland as a company commander when the Enola Gay drops its bomb on Hiroshima.

There’s a China diversion, but soon Jack is back in the States, married to a college sweetheart, in graduate school, headed for a college teaching career in languages. That didn’t work, but the French, Japanese, Chinese and Spanish he’d picked up along the way landed him a job with the United States Information Agency’s Latin American program; his first stop was Bolivia.

That, very briefly, takes him to 1961 and his first job with the new Peace Corps, as director of Latin American programs. He was 41 years old and we’re just past the first third of the book—including that out of sequence beginning 1966-1969 chapter. We’ve met warriors, boxers, diplomats, heads of state, academics, and Peace Corps Volunteers; he has named many of them, and they come in and out of his life like boxing and the Spanish language. We don’t learn much about the college sweetheart, but eventually, know that the marriage wasn’t happy and didn’t last and that he later married a returned Volunteer he affectionately calls “Lefty.” Chapters often begin with quotes from his letters to Lefty.

If you were in the Peace Corps or on staff anytime from the beginning to 1969, you’ll find people and events you know. If you have a Latin American interest; if you are an activist for women’s rights, social justice, or the environment, you’ll find people and organizations you know—or maybe have worked with—from Planned Parenthood to the National Urban Coalition to the Nature Conservancy. And the Peace Corps connections continue; Jack hired my old Peace Corps Fellow friend, Jon Darrah, as his aide when he’s named dean at Florida International University much later in his career and the book.

This is an autobiography and not a memoir. It’s a mostly chronological story of a remarkable life, which somehow misses some central gut issue. Jack loved the Peace Corps; he put his job as director at the head of the book with reason. But if you want to know what it’s like to be a Peace Corps Volunteer—or any sensitive human struggling with language and culture, to be young and sometimes lost in another land, to fall in and out of love—with other humans, with villages, with distant parts of the world, it’s not here.

There is boxing, languages—especially Spanish, human rights, international diplomacy, environmental activism, and life among rich, powerful, arrogant, bold, and often foolish nations’ leaders; but never a full portrait of any one of them. His admiration for John Kennedy and Sarge Shriver is immense, and for Warren Wiggins and Jon Darrah and many others, is noted. But we don’t learn anything new and personal about them. Or maybe about the soul of Jack Hood Vaughn. We get the facts, the people, the countries, and the organizations that fill his life. And what a life! It is dizzying. But we don’t get the stories of falling in and out of love—with women, or even with a country.

Maybe this is about the difference between autobiography and memoir, the one the story of the stories that make up a life, the other the intense and personal stories of a life’s signal moments. You have your own favorite Peace Corps memories and maybe memoirs of others. There are dozens of them, commercially and self-published. My yardstick is Moritz Thomsen’s Living Poor, the first PC memoir I knew. I read the first pages of Living Poor in the Volunteer magazine in my Turkish village almost 60 years ago, and remember viscerally still Moritz’s frustration with the slow work of his Ecuadorian companions, and then him adopting their diet and counting the minutes he could work on one banana.

Most recently, I love Ursula Pike’s Peace Corps memoir, An Indian Among Los Indígenas: A Native Travel Memoir. Pike, an American Indian, was a Volunteer in Bolivia–ironically, for the purpose of this essay, the place where Jack Vaughn’s life in foreign service began. Her struggles, from getting into the Peace Corps and through training as a brown American to relations with fellow Volunteers and Bolivians, is a strong—and maybe first ever—accounting of an indigenous American’s internal dialog about indigeneity in another land. It is, in this time of growing awareness that Indians are still with us in our own country, a critical concern for the Peace Corps—and for returned Volunteers continuing to work for peace and justice at home and in our second countries around the world. I wish Jack had lived to read it.

When Leif Christoffersen next comes to town, I’ll ask him about the Norwegian Volunteer program—I spent time with them during my year as a Peace Corps Fellow and just learned that Norway is now doing “North-South exchanges,” still sending Norwegians abroad while bringing volunteers from what we once called developing countries to work in Norway. This would be of interest to Jack—and should be to all of us who worked as Volunteers in other countries.

And I’ll give Leif Ursula Pike’s book in answer to why I have stayed in this small, Eastern Oregon place for 50 years. It’s the Nez Perce Indians, who lived here for 16,000 years before White America forcibly removed them in 1877. There is now great sentiment for welcoming them home, and I and Leif’s son—who had worked in Israel, Australia, and Africa before settling here-sometimes get to work on this homecoming for Indians together.

When we have our next cup of coffee, we’ll talk about Ursula Pike and about Jack and his book, and we’ll wish that he was here to join us. Although I have faulted him, I’d love him to be in the room. And I wouldn’t ask for more information about his marital relationships or come up with questions about how he and former Volunteer Spencer Beebe started Ecotrust.

What I really want to ask him is how he turned himself from a Marine Corps warrior in the Pacific Islands to a warrior for peace in the world, about what exactly went on in his heart and mind when he was done with war and looking for peace. About what we can all pluck from that mysterious conversion that might turn “kill the gringo” to “we’re all gringos somewhere—and let’s get along.”

My friend Leif grew up in Norway, went to college in Edenbourough, married an American and became a citizen, and had a career working for the World Bank. His son heads up a local natural resources non-profit, and when Leif comes to town we always have coffee or lunch and talk international.

On his last visit he asked whtehr I knew Jack Vaughn. Yes I said, I was a Peace Corps Fellow in 1967-68 in Washington D. C, when Jack was Peace Corps Director, and we had the pleasure of frequent meetings, and sometimes got to attend meetings with country directors when they came to town.

Leif had served on the board of Earth University in Costa Rica with Jack, and before he left town had a copy of Jack’s autobiography, Kill the Gringo, in my hands. It’s a fast read—and what a life!

I don’t have a lot of strong memories of Jack, though do remember going to a country directors’ meeting and listening to South America directors complaining about CIA and Defense Department officieals showing up at remote sites with bottles of booze. As I recall, Jack assured them that the boundary between the Peace Corps and the CIA was a firm one, and he would make sure that State and Defense and the CIA would get the word. (Later, when I was on staff in Turkey, Director Jack Corey backed the ambassador down when he wanted a volunteer who had spoken out agains the Vietnam war in the Englsih language daily removed from the country,)

•

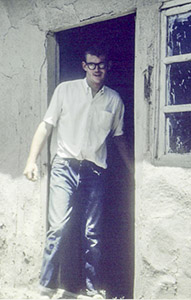

Rich at home in Turkey

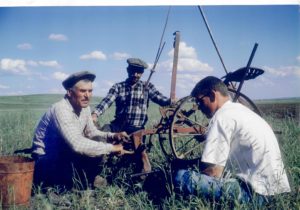

Rich Wandschneider came to the Wallowa, Oregon, 50 years ago, after five years as a Peace Corps Volunteer and staff member — four years spent in Turkey. He’d graduated from UC Riverside with a degree in philosophy and a minor in rugby, tried a year of grad school at Northwestern and been miserable.

A small Turkish-Kurdish village felt immediately comfortable in 1965, as Wallowa County did six years later. His first work was for the Extension Service as a “community development” worker, which introduced him to the broad geography and story-telling population of the county. Launching a bookstore — the Bookloft—in 1976 led to more meetings and stories, and ultimately to meeting Alvin Josephy and launching Fishtrap.

Wandschneider directed Fishtrap, a non-profit promoting writers and writing in the West, for 20 years, bringing scores of writers and wannabe writers to the Wallowa while helping local writers develop their talents. In 2011 he took the books that Alvin Josephy had left to a new art center in Joseph. The center took on Alvin’s name, and Rich now heads the “Josephy Library of Western History and Culture” in the “Josephy Center” on Main Street in Joseph.

No comments yet.

Add your comment