Talking with poet Bill Preston (Thailand)

The poems in Strange Beauty of the World invite readers to reflect on the ways the past impinges on the present, how events long ago continue to inform who we are now; to consider acts taken and not taken, and the way actions have unintended consequences; to bear witness to cruelty and injustice; to summon the creative imagination to resist the mundane, challenge the rehearsed response. In particular, they pay homage to beauty, and its weird, wonderful diversity and expression.

As with many aspects of his life, Bill Preston never started out to be a poet. Nor does he really think of himself as one: Strange Beauty of the World is his sole collection of poems, and he currently has no plan to write another. Not that planning has ever been his particular strong point. In fact, Bill never planned on joining the Peace Corps, choosing to serve in VISTA first, only joining Peace Corps in Thailand some years later. He didn’t plan on working with Lao and Khmer refugees immediately after Peace Corps, but interviewed refugee families in 1980, when there suddenly was a need for that work. After graduate school, he didn’t plan on returning to Southeast Asia, but he was offered a job supervising English teachers in a refugee camp in Indonesia, one he couldn’t refuse. He never set out to work in publishing, but changed careers to work as an editor for several educational publishers over three decades. Upon retirement, Bill didn’t expect to work for the New York City Civic Corps, but jumped at the chance to reconnect with similar work he’d done at the very beginning of his peripatetic career. Motivated by restlessness, as much as by idealism or any clear or coherent plan, his life has taken many an unexpected turn. The poems in Strange Beauty reflect aspects of that life, serving both as a looking back and a summing up.

Bill, where and when did you serve in the Peace Corps?

I served in Thailand from 1977-1980.

What was your Peace Corps project assignment?

I had three assignments. I was an English teacher in a Thai secondary school my first year. I taught several English classes and did some teacher training with Thai colleagues in the English department.

In the second year, I joined a new initiative between Peace Corps and the Thai Ministry of Education. The project assigned pairs of PC secondary English teachers to work with Thai counterparts in different educational regions throughout the country. Each region included several provinces. The focus was teacher training. My PC partner and I each team-taught English with a Thai colleague in selected secondary schools in two provinces, one semester in each province. Additionally, we conducted teacher-training workshops with English teachers at our respective schools. During semester breaks, we conducted training workshops in other provinces.

Extending for a third year, I worked at the British Council in Bangkok, assisting with the Council’s intensive English seminars for Thai secondary teachers. Utilizing the Council’s excellent listening lab and course books, a fellow Volunteer and I worked with teachers on listening, speaking, reading, writing, grammar skills, while British staff focused on teaching methodology.

Tell us about where you lived and worked in-country.

I was fortunate to live and work in a number of different cities and provinces. First-year I lived and taught English in Yala, a province in the far south bordering Malaysia. Yala and several other southern provinces were once part of Malaysia, and the region has a large Muslim population, making it culturally diverse.

During my second year, I lived and worked in several north-central provinces. My partner and I began the year by teaching a three-week intensive English workshop in Sawankhaloke, with about 24 participating teachers. For our first-semester assignment, we each taught in a different secondary school, paired with a Thai counterpart, in nearby Sukhothai province. The original Tha capital, Sukhothai has some impressive ancient ruins outside the modern-day provincial capital where we worked. We were fortunate to have the chance to explore the ancient city on several occasions.

For our second semester, we moved to adjacent Phitsanuloke province, team teaching at different secondary schools. As in Sukhothai, we conducted training workshops at our respective schools. At semester end, we taught an intensive training course in Tak province, bordering Myanmar, rounding out an ambitious year of teaching and training.

After home leave, a fellow Volunteer (from our PC group Thai 58) and I moved to Bangkok and worked at the British Council. Among other things, the Council conducted nine-week intensive language seminars for Thai secondary English teachers, in cooperation with the Thai Ministry of Education and Peace Corps. I really enjoyed working with the Thai teachers, who came from all parts of Thailand. My partner and I also made site visits to many of their schools to follow up the seminars. I learned a great deal about teaching English from the British staff, their methods and materials; my experience there, together with that of my previous two years, influenced me to pursue an MA in English as a Second Language following Peace Corps and, later, an editing career in ESL publishing.

What have you done since the Peace Corps? What are you doing now?

Immediately after Peace Corps I remained in Thailand and worked for several months interviewing Lao and Khmer refugees who had fled to Thailand from the Pathet Lao and Khmer Rouge, respectively. Working for the Joint Voluntary Agency in Nongkhai and Phanat Nikhom refugee camps, I interviewed families seeking resettlement in the U.S. Several poems in Strange Beauty of the World draw on that experience.

Interviewing Lao refugees at Nongkhai camp, Thailand

After that work, I moved to Honolulu to earn an MA in ESL at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. I received my degree at the end of 1981. While in Hawai’i I taught an academic ESL writing course at the university, taught beginning-level English classes to Southeast Asian refugees in an adult program, and taught foreign students in an intensive, nonacademic English program on campus. In the fall of 1982, I returned to Southeast Asia to supervise Indonesian teachers of English in Galang refugee camp, Indonesia, as part of a consortium comprised of the Experiment in International Living, Save the Children, and the U.S. Department of State. Returning to the U.S. the following year, I was ESL supervisor in a program for adult refugees at Catholic Charities Diocese of Stockton, California.

In the mid-1980s I transitioned from English language teaching to educational publishing. Over three decades I worked as an editor of English Language Teaching (ELT) books and materials for a number of publishers, mostly in New York. While working for Pearson  Education, I wrote A Sense of Wonder, a multicultural literature anthology and reading-writing text for ESL/EFL students. This project was particularly meaningful because I was able to address my twin passions for literature and language teaching. The anthology also gave me the opportunity to share work by poets, playwrights, essayists, and short story writers that I greatly admire. My last editor job, for National Geographic Learning, was based in Singapore, providing the opportunity to live and work in Southeast Asia for a third time. It was exciting to have access to National Geographic’s spectacular photo archives and diverse range of magazine articles, and adapt them for ELT courses.

Education, I wrote A Sense of Wonder, a multicultural literature anthology and reading-writing text for ESL/EFL students. This project was particularly meaningful because I was able to address my twin passions for literature and language teaching. The anthology also gave me the opportunity to share work by poets, playwrights, essayists, and short story writers that I greatly admire. My last editor job, for National Geographic Learning, was based in Singapore, providing the opportunity to live and work in Southeast Asia for a third time. It was exciting to have access to National Geographic’s spectacular photo archives and diverse range of magazine articles, and adapt them for ELT courses.

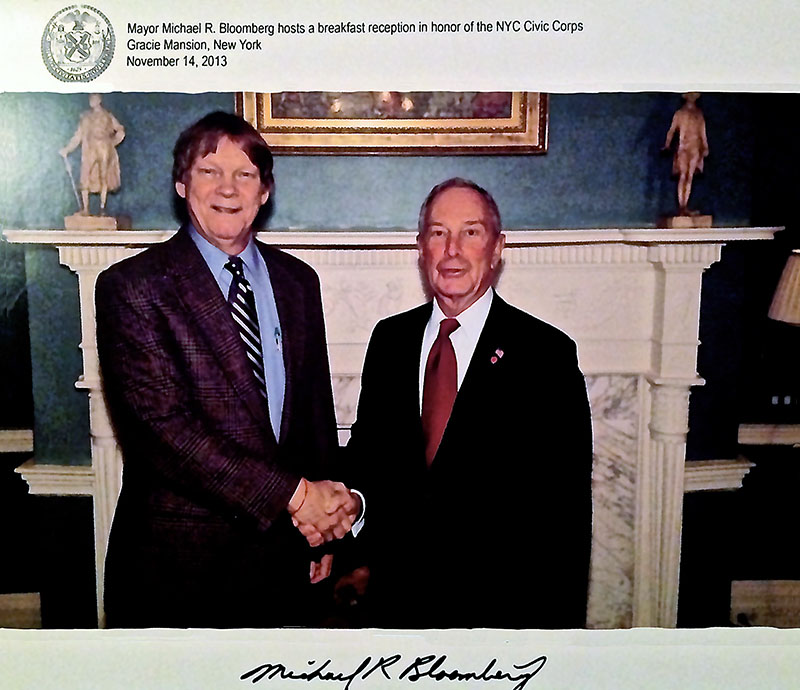

Following Singapore, I was a volunteer with the NYC Civic Corps, where I worked at a nonprofit agency that helped engage New York City public school students in service-learning projects. During that year, then NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg (who helped sponsor the program) invited the volunteers to breakfast at Gracie Mansion.

Meeting Mayor Bloomberg at Gracie Mansion, NYC

I retired in 2014. Currently, my wife and I divide our time between been New Jersey and Florida. These days, I read a lot, do some photography, a bit of writing, a little volunteering, travel, running, and hiking.

How would you describe your new poetry book Strange Beauty of the World in one sentence?

(Deep breath:) Many poems in Strange Beauty of the World touch on aspects of childhood, growing up, travel, volunteering, work, and family life, while others deal with clothes, food, jazz, movies, birds, dogs, dreams — stuff like that.

What prompted you to write the book? How long did it take?

I’ve been a scribbler, on and off, most of my life. At various times I’d jot down thoughts about what was going on at the time, kept a sporadic journal. Sometimes this scribbling included poems, usually in longhand, in a notebook or on the odd piece of paper.

When A Sense of Wonder was published in 2003, it encouraged me to write more. Up to that point I’d published a journal article on teaching poetry to foreign students based on my Peace Corps experience in the December 1982 volume of TESOL Quarterly, and had edited a number of ELT course books. Subsequently, I wrote some short pieces about my time in Thailand; one story, Snow in Sawankhaloke, (describing the training workshop there) appeared in the 2011 anthology of Peace Corps stories Even the Smallest Crab Has Teeth, edited by Jane Albritton (India), and several reviews of books written by former PCVs. I continued to write poems from time to time but never imagined publishing them. The poems were rough — what I, in more optimistic moments, considered works in progress.

When A Sense of Wonder was published in 2003, it encouraged me to write more. Up to that point I’d published a journal article on teaching poetry to foreign students based on my Peace Corps experience in the December 1982 volume of TESOL Quarterly, and had edited a number of ELT course books. Subsequently, I wrote some short pieces about my time in Thailand; one story, Snow in Sawankhaloke, (describing the training workshop there) appeared in the 2011 anthology of Peace Corps stories Even the Smallest Crab Has Teeth, edited by Jane Albritton (India), and several reviews of books written by former PCVs. I continued to write poems from time to time but never imagined publishing them. The poems were rough — what I, in more optimistic moments, considered works in progress.

Years later, going through boxes of stuff in the basement, I unearthed a folder containing poems I’d written over the years — some still in longhand, others I had typed up. They were a loose collection and still rough. Reading them again with the passage of time, I saw that the poems addressed certain themes — childhood, youth, the Vietnam War and its aftermath, Peace Corps, work, travel — as well as various observations and imaginings. It occurred to me that, if I revised the poems and wrote some others to further flesh out the  themes, there might be material for a book. From that point on — over about three years — I periodically revised, wrote, and revised again the old and new poems. I named and renamed different thematic sections, moving some poems around until they seemed to fit. The result of this drawn-out process was Strange Beauty of the World.

themes, there might be material for a book. From that point on — over about three years — I periodically revised, wrote, and revised again the old and new poems. I named and renamed different thematic sections, moving some poems around until they seemed to fit. The result of this drawn-out process was Strange Beauty of the World.

Talk about your writing process. Where do your ideas come from?

When I write basically anything, it’s typically slow going. I’m not much of a first-thought-best-thought kind of person. I’m a plodder. With poetry, it generally starts with a stimulus, something that grabs my attention, triggers my imagination, generates a response. Often, it takes time and some revision to feel like I have something to say, accompanied by self-doubt as to whether I can express it. Having worked as an editor was not especially helpful, more of a hindrance. I had to block my editing self to let my writing self get through.

Ideas for poems come from many sources. I recall Wallace Stevens wrote somewhere that “It’s not everyday that the world arranges itself into a poem.” I believe Stevens got ideas for his poems while walking to and from his VP job at the insurance company in Hartford, Connecticut. Which goes to show you never know where, or when, inspiration may strike. I try to be open and receptive to ideas and stimuli that might kick-start my imagination. If I’m sufficiently attentive, nimble — and the muse is in a pleasant mood — I may respond with a poem, or some fragment thereof. Some examples from Strange Beauty might illustrate.

Different things pique my imagination and get the poetic ball rolling. Memories are a big source. “The past,” Neil Young wrote in his memoir Waging Heavy Peace, “is such a big place.” Sure is, especially when you’re old, with so much past to draw upon. In writing Strange Beauty, particular vivid memories from childhood and youth presented themselves: an air-raid drill from the early Cold War years (“Waiting for the Big One”), a coveted item of clothing (“Tennis Shoes”), news of JFK’s assassination (“Dr. Hill Breaks the News”).

It’s not really clear why certain memories emerged and not others. Strange, too, how long-forgotten memories could surface out of the blue. Around fourth grade, I wrote a short description (my mom saved the paper, written in my jagged scrawl) of a winter night my dad had driven our family home from New York City in a heavy snowstorm. The image of our ’53 Ford’s headlights ‘eating the snow like vacuum cleaners’ came to me again some fifty years later, as I was writing he poem “Snowy Evening, Driving Home.”

Work, volunteer, travel, and family experiences were grist for the mill: reconsidering a summer job during college (“Get a Job”), searching for the ultimate dessert during Peace Corps (“Of Rice and Mangoes”). Once on a business trip in Costa Rica, the rep I traveled with took me to a restaurant, which had a hand-printed sign: No Se Permiten Escenas Amorosas. My Spanish, severely limited, did not stop me from contemplating what might constitute escenas amorosas — ‘love scenes’ in my errant translation — (“Lost in Translation”). Observing renovation to the Porch of the Maidens on the Acropolis in Athens got me imagining a newspaper ad for a caryatid (“Athens Personal”). And stepping into my son’s empty classroom set off a rush of memories from my own second-grade class decades before. (“The Music of Vacant Classrooms”)

Some poems took an unexpected turn, landing in a different place from where they started. The poem “Guns” began as a kind of list poem — an inventory of various toys I’d had as a child. It segued to a game my friends and I had sometimes played, where we would pretend to shoot each other with imaginary guns. Then, out of nowhere, I recalled an incident in which my brother Gary and I had found two real pistols —radically shifting the mood of the poem.

In one case the sound of a name — French painter Raoul Dufy — called forth a poem. “Row-ool Doo-fee!” The way his name rolls off the tongue prompted me to write the eponymous poem, with stanzas ending in words to rhyme with Dufy.

Did you belong to a writers group and share reading and critiquing, or have any other way of bouncing off your writing and thinking?

I didn’t belong to a writers group. Basically, I wanted to wrestle with myself to work out what I had to say and how to articulate it. Of course, feedback is essential as a reality check. Two readers reviewed the manuscript of Strange Beauty. The first was a good friend and writer from my publishing days, who read an early draft. Later, after Peace Corps Writers agreed to publish the book, my editor reviewed the revised manuscript. Both readers raised valuable questions concerning accuracy, clarity, verbosity, clichéd or pretentious language, and other pitfalls, which helped me to revise further and make improvements. I am indebted to both, and am responsible for remaining errors or flaws.

Which Peace Corps writers have you read? Have particular writers—RPCV or not—influenced your work?

Over the years I’ve enjoyed reading novels and stories by a number of Peace Corps writers, including Paul Theroux (Malawi), Norman Rush (Botswana), Kent Haruf (Turkey), Bob Shacochis (St. Vincent), P.F. Kluge (Micronesia), John Coyne (Ethiopia), Patricia McArdle (Paraguay), Lawrence Lihosit (Honduras). I’ve reviewed books by three of those authors for Peace Corps Worldwide. I’ve also read articles by Peter Hessler (China), George Packer (Togo), and Maureen Orth (Colombia).

Various influences come to mind, starting from early childhood. When I was around three or so, at bedtime my mom read me a poem called Eletelephony by Laura Richards. That was the first time I recall laughing — out loud, hysterically, over and over — at the way a writer, in this case Richards, was using language in silly, playful ways. Soon she started reading me Dr. Seuss, who further hooked me on the fun, imaginative possibilities of language. Some time later I discovered Ogden Nash’s poems (I detect Nash’s fingerprints all over my poem “The Spider.”) James Thurber’s cartoons and stories were another early influence, as were the satirical writers for Mad magazine. In a similar vein, I got a big kick out of singer/songwriter Allan Sherman’s early-’60s album My Son, the Nut, with his many clever song parodies. (Incidental aside: Sherman is the only songwriter I know to have referenced, yes! the Peace Corps — in his song Sarah Jackman, sung to the tune of Frère Jacques: “How’s your nephew Seymour? / Seymour joined the Peace Corps” — no doubt planting an early seed in my adolescent brain.) On TV, I enjoyed the whacky, tongue-in-cheek humor of Rocky and His Friends, and, in high school, the freewheeling, zany humor of Steve Allen. Clearly, there’s a pattern here, and one reflected in what I’d call the more screwball poems in Strange Beauty.

I tip my hat to two particular poets in Strange Beauty. I’m a big fan of Richard Hugo’s work, especially his poems on dreams and stones. Also a fan of film noir, I tried to tap into the surreal feeling and sense of dislocation that characterize Hugo’s dream poems in writing “In Your Dream Noir,” which I dedicated to him.

“The Museum of War is Kind” came about in the aftermath of a 2013 visit to the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City. The museum presents in excruciating detail the effects of the French and American wars with Vietnam. While some might dismiss the museum as communist propaganda, for me the impact of the cumulative evidence was undeniable and devastating. Particularly disturbing were the many display cases filled with guns, mortars, bombs, mines, napalm — an overwhelming arsenal of war, laid bare in naked, brutal physicality. In a courtyard outside stood a guillotine, complete with angled knife blade poised above an empty basket. Most people, including those who fight in war, never confront such an array of weapons and machinery designed with the sole purpose of maiming and killing. We all should, we’d learn something. Shaken by the experience and writing about it later, I recalled Stephen Crane’s poem “War is Kind,” with its ironic, savage litany of war’s tragic consequences. The title of Crane’s poem became part of mine.

A great many other poets have been an inspiration. Generally speaking, I’m drawn to poets who tell good stories and take me out of myself to see things from unique perspectives; who express outrage at injustice and inequality; who reveal deep awe and appreciation of nature; who are attentive to the strangeness and beauty of everyday life; who have a sense of humor and don’t take themselves too seriously; who — as Emily Dickinson put it — tell the truth but tell it slant. I believe their spirit is reflected, in some way or another, throughout the poems in Strange Beauty.

Two essential resources: Garrison Keillor’s podcast The Writer’s Almanac has been enormously valuable in introducing me to so many poets; likewise, former U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith’s podcast The Slowdown. Check them out if you love poetry and have never done so.

What have you learned in writing this book?

Writing is a personal challenge, a struggle with my limitations. Working on Strange Beauty, I was reminded again that writing is a humbling experience. With poetry, in particular, every word counts; you really have to pare things down. For me, this involved a lot of revision. Revising was mostly a process of subtraction, eliminating whatever was unnecessary. I am by nature disinclined to revision, so that process was really good discipline. Not that I succeeded in separating out all the chaff, but I tried. Architect Maya Lin has described her approach this way: “My goal is to strip things down so that you need just the right amount of words or shape to convey what you need to convey.” That’s so well put, and a worthy aspiration for writers too. Spend time at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., and witness how brilliantly she actualized her goal.

Even with revising and paring down, it’s difficult to get at what you want to say. Language is elusive, memory unreliable, words imprecise. The temptation to show off or explain is always lurking. Billy Collins has an analogy that seems apt, regarding the perils of writing poems —s omething to the effect (and I paraphrase) that starting a poem is like stepping into a canoe: a lot of things can go wrong. I know the feeling. Strange Beauty was a struggle to steady the boat, navigate my way through various pitfalls.

Poems sometimes feel incomplete or unresolved. To push the Billy Collins metaphor, ending a poem —stepping out of the canoe, as it were — can pose its own issues. Just as you need to work out how to begin and sustain a poem, you have to know when to stop. When a poem resolves itself naturally, it’s a joy. Sometimes, though, you fiddle and tinker with the ending, or try to impose one. This is frustrating and not a great idea because you can’t — I can’t — really fine-tune a poem like a machine or radio station. In “The Cambodian Musicians and Dancers Perform on Christmas Night,” I wasn’t satisfied to let the poem stand after having described the performing musicians and dancers. I felt compelled to add a stanza to make some final point. I struggled for months, revising that stanza over and over, trying to express some concluding idea or observation — never finding a completely satisfying resolution.

Revisiting parts of my past to write this book, I realized how fortunate I was, and am, how privileged to have had a wonderful childhood, a good education, opportunities to travel, to do work I enjoy, to volunteer and give back. In a small way, Strange Beauty is my acknowledgement of all that, and an expression of gratitude.

What would you like readers to take away from reading your book?

I’d like readers to make personal connections based on their experience. Writing and reading are a reciprocal process, two sides of a coin. When readers connect with something they read, the writing becomes a shared experience, reaching beyond the writer’s individual experience and peculiar imagination to reflect something broader, more universal. In that larger sense, the poems have value to the extent that readers bring their experience to bear. Without such communion between writer and reader a book is just so many pages and letters.

What are you doing to promote your book?

I’ve posted on social media, on Facebook and Linkedin, to make people aware of the book. Soon after publication, Peace Corps Worldwide sent Strange Beauty out for a review, which I subsequently posted. The reviewer was most supportive, which was gratifying and much appreciated. Who knows, perhaps these comments will pique further interest. Anyway, I’m happy to share them. Beyond that, it’ll be great if lots of people read the book, but I’m not going to beat a drum, blow a horn. The world is noisy enough as it is. Some quiet word-of-mouth support would be fine, though.

I’d like the poems to speak for themselves. Returning to an earlier point, I hope readers, however few or many, connect personally. Perhaps some readers will be moved to write their own poems. Wouldn’t that be something?

No comments yet.

Add your comment