Review — KILL THE GRINGO by Jack Hood Vaughn (PC Director)

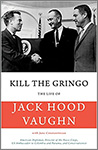

Kill the Gringo: The Life of Jack Hood Vaughn

Kill the Gringo: The Life of Jack Hood Vaughn

Jack Hood Vaughn with Jane Constantineau

Rare Bird Books

May 2017

389 pages

$17.95 (paperback), $11.03 (Kindle)

Reviewed by Randy Marcus (Ethiopia 1966-67)

•

“Everybody knows that Sargent Shriver was the first director of the Peace Corps. Only my wife remembers who the second one was.”

SO COMMENTED JACK VAUGHN years after his Peace Corps stint. Sargent Shriver, John F. Kennedy’s brother-in-law, was a charismatic whirlwind who had built a national reputation as the creator and embodiment of the Peace Corps. Compared to Shriver, Jack Vaughn was no rock star. He certainly had the creds: an experienced USAID hand, a regional director in the Peace Corps under Shriver, Ambassador to Panama, and an Assistant Secretary of State. He was, however, a prosaic Lyndon Johnson protégé, not a glamorous Kennedy acolyte with the glow of Camelot.

I had started my Ethiopia-bound Peace Corps training in 1965 under Shriver and resumed it in 1966 under Vaughn (in a one-time, two-summer training program at UCLA). Jack Hood Vaughn? Who the hell was this guy? That’s what I wondered upon graduation as I glanced at my newly issued Peace Corps Volunteer ID card with his signature on it.

This memoir answers that question. Vaughn was a man of many talents and many jobs. His autobiography is a compendium of anecdotes, an enjoyable read for current or former Peace Corps Volunteers, foreign policy wonks, Latin America hands, environmentalists, or anyone with an interest in the headline personalities of the 1960s.

A would-be reader might think the title refers to the chants of anti-American demonstrators who were always protesting US policies in Latin America. In fact, “mata al gringo” was directed at Vaughn years earlier when as a college student, he made his debut as a professional boxer in Juarez, Mexico. He was earning credentials to become his school’s head boxing coach. His life was at considerable more risk during his service with US Marines a few years later in the battles of Einewetok, Guam, and Okinawa.

Vaughn survived Japanese bullets to use his other talents as a linguist. After a short and less than stellar academic career, he found his calling working abroad. He joined the fledgling US Information Agency as a program officer in Bolivia, Costa Rica, and Panama. Vaughn was a naturally gregarious outgoing sort. He made friends easily among host government officials and ordinary folks — a talent that would stand him in good stead as a future ambassador and Peace Corps director. He encountered all kinds of characters from presidents to military strong men to leftist radicals. One memorable encounter was with Ernesto Guevara, later to become the sainted leftist icon, Che. Guevara made it clear to Vaughn that he hated Americans— not just on ideological grounds, but also for a very personal reason. Some years earlier, three drunken American sailors had attacked him in Valparaiso, Chile, beat him savagely, and left him for dead.

In 1956, Vaughn moved from USIA to what later became the US Agency for International Development (USAID). After an initial tour in Bolivia, he expanded his geographical horizons to West Africa. It was during his tour as USAID director for Senegal, Mauritania, and Mali that he had the opportunity to escort Vice President Lyndon Johnson during a visit to the region. He later met Sargent Shriver in Senegal and helped him to lay the groundwork for a Peace Corps presence in that part of Africa. In both instances, he made a good impression. Shriver asked him to join the Peace Corps as regional director for Latin America. Vaughn jumped at the chance, considering himself a Peace Corps type at heart. A few years later, LBJ, recalling his visit to Mali, appointed him ambassador to Panama — just at the moment Panama broke diplomatic relations with the US following violent protests over the US-owned Canal Zone. A year later, after having restored diplomatic ties and calmed the waters (without resolving the underlying issue of the Canal), Vaughn received an even more challenging assignment —Assistant Secretary for Inter-American Affairs at the State Department.

Vaughn paints a vivid and a sometimes painful self-portrait during his year as assistant secretary. In 1965, civil conflict erupted in the Dominican Republic between leftist factions and military leaders Law and order broke down. Concerned about the safety of Americans in the DR and fearful of a Castro-type revolution, LBJ sent in US troops to quell the violence. He ordered Vaughn to stabilize the fractured DR political climate and win support for the US move from the countries in the hemisphere — a thankless and impossible task. Vaughn was not happy with the intervention and refused to sign off on it. However, he carried out his diplomatic marching orders as best he could. In one notable instance, LBJ demanded Vaughn draft a “white paper” that would lay out in detail all the steps the US had taken to avoid sending in the troops. In fact, it was minimal, but Vaughn gamely did his best to put lipstick on the pig. Johnson was not pleased. In front of the entire cabinet, Johnson harshly scolded Vaughn, calling him incompetent, lazy, disloyal, dense, inarticulate, and unqualified for any government position higher than a GS-3. Vaughn survived the humiliating dressing down, though, and eventually got back into LBJ’s good graces. One factor that may have helped win Johnson’s favor was their mutual antipathy of Bobby Kennedy. Vaughn almost got into a fistfight with the then New York senator over the DR, a story he recounts with great relish.

By 1966, US troops had been withdrawn and a political settlement achieved ending the bloodshed. Johnson rewarded Vaughn with his “dream job,” director of the Peace Corps. Even though Shriver was a tough act to follow, Vaughn buckled down and expanded the Peace Corps’ worldwide reach. He sought new ways to help PCVs become more valuable in their local communities. One reform was to “relax the rigid rule of separation between the Peace Corps and the State Department.” Foreign Service types were often quite skeptical about the young, untested PCVs. Vaughn helped change that attitude. He negotiated an agreement to enable PCVs to access the “ambassador’s fund,” a discretionary pot of money US embassies used for small development projects or emergency situations. As economic officer in our embassy in Togo in the 1970s, I provided those funds to up-country PCVs to help them build schools, markets, and bridges. It was a win-win for both the Peace Corps and US diplomacy.

I did learn a surprising bit of trivia from Vaughn’s time as director. During his confirmation hearing in early 1966, a senator brought up the issue of PCVs’ appearance and controversy over hairy hippie types offending some local government leaders. In response, Vaughn banned Peace Corps beards to eliminate the distraction. Yet, in late 1966, as a PCV teacher in Ethiopia, I grew a beard to look older. No one from the Peace Corps office in Addis Ababa said a word to me about it.

Vaughn also took steps to improve and expand language training. He introduced the concept of in-country training. He wrote that the first attempt at overseas training took place in Ghana in the summer of 1967. While that may have been the first group to be trained entirely in a host country, my group, Ethiopia VII (Advanced Training Program), may have been the first to go through at least partial in-country training. We student-taught summer school in Harar, Ethiopia in 1966 before being sent to our permanent locations. It was the best training we received.

The Nixon administration did not keep Vaughn, and he went on to have an unusually varied and eclectic series of jobs in academia, children’s television, Planned Parenthood, infrastructure development in Iran, conservation, environmental protection, as well as a return to USAID. Timing is everything, and as luck would have it, his job overseeing a TVA-like project in Iran again gave him a front row seat to history. Residing in Tehran during the late 1970s, Vaughn and his family witnessed the tumultuous events that led to the fall of the Shah and the growing anti-US sentiment that ultimately prompted a massive flight of expatriate Americans from Iran. Vaughn described the dangers and hardships he faced on a daily basis. He also wryly commented on the US ambassador’s failure to recognize the writing on the wall that was obvious to many American residents: the Shah’s regime was doomed.

Vaughn held a variety of wildly disparate positions, so a reader with particular interests might find parts of the book unrelated to those interests slow going. Nevertheless, evident throughout is Vaughn’s dry wit and feisty character. He was a happy warrior in the boxing and the political arenas. Those of us who served as PCVs during his tenure can be grateful for his efforts to ensure that Shriver’s creation would endure as a permanent US government entity — one that to this day still embodies the best America has to offer to the world.

•

Reviewer Randolph Marcus taught secondary school students in Asella, Ethiopia in the mid-sixties before joining the Foreign Service in 1969. During his diplomatic career, he served in (then) South Vietnam, Togo, Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina as well as in Washington, DC. Following his retirement from the State Department, Randy worked for the Air Force Office of Special Investigations and the Defense Department as a counterterrorism analyst. He is currently serving as treasurer on the board of directors of Ethiopia & Eritrea Returned Peace Corps Volunteers.

I appreciate the background info you have provided on Jack Vaughn.

While stationed at our embassy in Panama in 1967 I was assigned, because of my Peace Corps background, to escort Jack Vaughn on a visit to the country. I was told to keep the visit quiet since Vaughn was coming for rest and recuperation. It seems he enjoyed the horse races and ladies in Panama. I went out to the airport to meet him and quietly asked a personal friend who worked there to make suitable arrangements for a real VIP who preferred to keep his visit quiet. My friend immediately replied, “Oh Jack is coming.” He was well known and well loved by the Panamanians.

Jack Vaughn, in retirement, had come to New Mexico frequently, to visit former colleagues from early Peace Corps days. The last time we saw him was in Sept 2011, at the funeral of Andres Hernandez, a favorite son of New Mexico, and founding director of the Dominican Republic and Guatemalan PC projects.

Like, Jack, and so many of the founders of the Peace Corps, incl Pres Kennedy, “Andy”, as we RPCVs knew him, was a combat veteran of WW-2. A fact which is frequently overlooked.

Not long after that last visit, we learned that Jack had died. I think that for both Andy and Jack, although they had varied experiences before and afterward, their time with the Peace Corps remained in both their minds, amongst the most significant. JAT

I neglected to say that Jack’s final wish was to be interred at Arlington Nat’l Cemetery, in a “ground burial”. We RPCVs learned of this from his wife, Leftie. Despite our appeals and the intercession of New Mexico Senator Tom Udall, it wasn’t to be, and Jack found his final rest in one of the mausoleums there — but, significantly, surrounded by fellow Marines. JAT

Great review Randy and interesting comments from John and Leo. I returned to the US from Ethiopia in 1965, In 1967 my. Brother served as a Marine officer in Vietnam. He wrote that he and his fellow Marines were trying to give the Vietnamese people a chance at a better life as Peace Corps Volunteers had attempted to do in Ethiopia.

Thanks, Ed. I was involved in something similar. In my first Foreign Service assignment, I was detailed to USAID and worked for the joint civilian/military program, known as CORDS (Civilian Operations and Reconstruction Development Support). We did a lot of good things; the US role in sVN was not totally napalm/body count centered. In the end, of course, it was all for naught.