Remembering Ted Wells–The Old Man in the Bag

By David B. Levine (Ethiopia (1964-66)

Ted Wells’ The Old Man in the Bag and Other True Stories of Good Intentions is a wonderful collection of reminisces from Helen and Ted Wells’ first two of their three years as Peace Corps Volunteers in Ethiopia (1968-1971). Each of the twelve chapters is preceded by a copy of a letter home from them and accompanied by extensive photographs. The letters and stories add up to an overview of what was an exciting, path-setting, exhilarating, frightening, emotionally fraught, and extraordinarily impactful two years, both atypical and unique Peace Corps experience!

I knew Helen and Ted as PCV’s; in fact, I was instrumental in their receiving the assignment underlying the narrative and am actually named a time or two in the telling. Here is that background. First, I was a PCV in Ethiopia myself, from 1964-66 (Eth IV) as a teacher in Emdeber, in Gurage country, about halfway between Addis Abeba and Jimma. My then wife, Nancy Terry Langford, and I were PC/Ethiopia’s first “experiment” with assigning volunteers to what were described as “remote locations:” no all-weather roads, no running water, no electricity, no phone or mail service. During the rainy season, we were an eight-hour mule ride from Wolkite, the nearest town on the main road. (There is now an extensive system of all-weather roads to Emdeber and beyond, throughout Gurage country. Emdeber is now about a half-hour car ride from Wolkite.) Nancy and I were soon joined by Jack Caraco, an extending Eth II, and later by Phillip LeBel and Kathy Moore, Eth VI’s. Together we opened Gurage country’s first high school, starting the ninth grade in 1964, and adding another grade each year, with volunteers and Ethiopian National Service teachers regularly assigned. Phil LeBel remained for four years to see the initial students through their graduation.

In 1967 I was hired to work in a PC/Ethiopia training program, then invited to join the PC/E staff, initially as an Associate Peace Corps Director for the southern region, and then as Program Officer for the entire program. I remained on PC/E’s staff through late 1970. (I had a third incarnation with PC as Director of the Office of Program and Training Coordination under Directors Carolyn Payton and then Richard Celeste from 1977-1981.)

In the late 1960’s, resistance to Haile Selassie’s reign was growing, and student demonstrations and strikes were spreading from the University in Addis to high schools, especially in the larger urban areas where the bulk of PCVs were assigned. More volunteers were assigned to smaller, more rural schools, and under PC/E Directors Dave Berlew and then Joseph Murphy, efforts began to diversify the program, which until then was over 90% PCV teachers. With leadership from then Program Officer Gene Martin, programs in health were expanded and new initiatives developed in partnership mainly with the Ministries of National Community Development (MNCD) and Agriculture.

In 1968, under the guidance of Ato Aberra Moltot, MNCD’s Assistant Minister, we initiated a small program to support the effort to resettle Ethiopians, mainly Amharas, from overpopulated and depleted agricultural communities in the north, to relatively unsettled, sparsely populated, and extremely remote and isolated lands in the south, mainly in Gemu Gofa Province. The first of those assigned was Paul Jankura to a new settlement called Wajifo (he’s mentioned in Ted’s book). That assignment, while quite challenging, seemed to go well enough to encourage us to build on it. Helen and Ted sent to Shileh, and Ed Salt and Anne Grey Haynes, sent to Yirba Muda (I think!) were next.

These assignments were classically unstructured rural development. While areas of community need were identified as possible entry points for the volunteers, their task was to become members of the communities, assess needs, support community desires, propose projects, link possible government, donor, and private resources to those needs, and do what they could! The language was a challenge. Their Amharic was basic after training, and at the most, there may have been 2 or 3 English speakers, extension agents or elementary school teachers, in the general resettlement area. Even more challenging, the Ethiopian cultural and bureaucratic practices, and the Peace Corps regulations and capacity for support were often unknown, unclear, and at times counterproductive.

This is the situation in which Helen and Ted found themselves in late 1968.

The Old Man in the Bag captures these realities in extraordinary ways. Like most volunteers, those in these assignments were often frustrated and confused, unable to communicate the ideas behind their actions, caught going down dead-end roads, blocked by promises unkept, hampered by the lack of sounding-boards, and on 24-hour display. On the other hand, they found their way, solved problems they had never encountered before, discovered inner strengths of which they were barely aware, impacted individuals in ways both unanticipated and profound, identified and brought to bear resources from government and other organizations that were otherwise out of reach to these communities, and initiated many small and successful local projects. While they may not have transformed these resettlements into successful thriving towns, they, the villagers, and even the government and donors learned much from their efforts. And perhaps most important, they brought that special PCV optimism and refusal to give up that fostered their own growth and left a lasting impact on many of the individuals with whom they dealt.

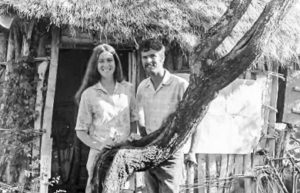

All this is evident in The Old Man in the Bag. We start with Helen and Ted in PC training in St. Croix, strong, outdoorsy, competent and self-reliant, relatively newly married individuals, already dealing with mysterious PC decisions, venturing out on their own into a natural setting unknown to them, and needing to find their way through a cross-cultural encounter with a Cruzan family. The conflict of good intentions and cultural realities continues in many ways throughout the book.

When Helen and Ted arrive in Ethiopia, their intended assignment as urban community development workers proves to hold little interest for them, and instead, they are offered and eager to accept going to Shileh, a resettlement effort in Gemu Gofa Province. Their initiative in getting there proves precipitous and they arrive unaccompanied by a government official and without a formal letter of introduction. So, they need to return to Arba Mench, the provincial capital, obtain the letter, and return to Shileh – where now they are welcomed with smiles. Struggles with bureaucracy and formal vs. informal strategies are another recurring theme.

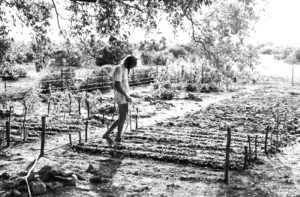

In many of the vignettes, Helen and Ted function independently of each other, with Helen focusing on health, gardening, and cattle-related activities, primarily with the women of Shileh, and Ted on town planning, house construction, and engagement with the decision-making processes of the men. Their separate activities lead to several situations – e.g., the fear that Helen has been eaten by a lion or that Ted’s bicycle has been shot at – that usually show the ongoing development of their cultural and situational understandings and the growing strength of their relations with the community.

There are many insights about the value of their resources and privilege in deciding when and how to absent themselves from Shileh, whether to head to Addis to meet PC requirements or obtain resources, or to Arba Mench to meet with officials, or to do their own local explorations. They have no real assignment supervisors, no regular PC staff contact, only occasional contact with the provincial government, and exceedingly rare visits by or to other volunteers. We see the dual edges of this, the periodic confused decision-making, the unclarity of paths to be taken, the waves of culture shock and depression, and the stresses on their marriage.

Shileh is isolated during the rainy season, and we see the impact of needing to supply one’s life – food, health, work necessities – on a seasonal basis, the costs of not having what one needs, the constant struggles to preserve food and materials against insects and other invaders (baboons, e.g.), and how those issues become just a part of life, and, at least in Ted’s telling, not major factors in their adjustments over the years in Shileh.

There are wonderful high points: relationships established or bridged; true utilization of their skills and intelligence; increased integration into the community; success in overcoming major challenges to Shileh; a vacation to Kenya.

Throughout the book and most clearly in the letters home – what remarkable penmanship these letters home display; those I sent as a PCV were barely decipherable! – Ted is clear that Vietnam and his draft status were his primary PC enlistment motivations; it was that or head to Canada. That issue is resolved when he gets a high draft number and is no longer likely to be drafted. And then they are asked to extend for a third year to help plan and establish a new town in an even more remote location, Kelam, near the Ethiopia/Kenya border in an area with virtually no Amharic, let alone English speakers. Their decision, characteristic of them – and perhaps many PCVs – comes down to weighing personal commitments to the new Kelam Governor who is eager for their skills and company and whom they like and value, against the desire to return home and to escape the harsh realities of their two years. They opt to stay, and we can only imagine what that experience was like as the book ends after a visit to Kelam but prior to their taking up that assignment.

Ted has taken us on a marvelous tour through an incredible PC tour of duty. We learn much about Helen and him, much about development, and most importantly, much about the power of the PC experience and why it has had such a positive impact on so many of us, despite the almost unbelievable struggles it has put us through. We owe Ted and Helen a great debt for this book.

One final thought about the power of youth and naivete, and perhaps the differences between 1968 and 2021. In retrospect, I think I and Peace Corps were either incredibly brave or incredibly stupid in sending volunteers into these kinds of assignments with the little support we gave them. Yet, when the correct volunteers, such as Paul, Ted, Helen, Ed and Anne were sent, they did marvelous work, and they matured into adults carrying the commitments and character they showed and the skills and attitudes they developed through the many subsequent decades.

Would we now think it a good idea to transplant subsistence farmers from one cultural milieu to one totally different, from one ecological zone to another totally different, to imagine that unsettled land is ripe for clearing and resettlement, to do all that without in-depth study, consideration, and local leadership and guidance? Probably not, but I rejoice in the efforts PC undertook and the experiences and success it provided to volunteers like Helen and Ted Wells.

Read The Old Man in the Bag and Other True Stories of Good Intentions and enjoy and learn from it.

Old Man in the Bag

Old Man in the Bag

by Ted Wells (Ethiopia 1968-71)

Create Space Publisher

286 pages

November 2012

$4.95 (Kindle); $21.95 (Paperback)

New Yorker David Levine (Ethiopia 1964-66) joined the Peace Corps after graduating from Columbia University. He worked on the Peace Corps/Ethiopia staff from 1967-70 and next managed the President’s Office at Queens College/CUNY from 1971-75 and subsequently the Antioch School of Law from 1975-77. He returned to Peace Corps Washington as Director of the Office of Programming and Training Coordination from 1977-81. In 1981, he became an independent consultant focusing on international development and specializing in program design and implementation, problem-solving, consensus-building among development partners, and executive coaching. He worked worldwide in field and HQ offices, with a major focus on sub-Saharan Africa. Now retired, David remains engaged with issues of international development and spends much of his time mentoring people interested in pursuing international development careers, including the Peace Corps.

David,

A wonderful write-up – eager to read the book so as to remember that very important time in our lives. Had no idea you are a New Yorker. I lived there (West Side) from 1964-968 & 1974-2000 Still miss NYC’s energy & diversity. Moved to Kutztown, PA in 2000 to join my husband who was then teaching at Kutztown University. He retired in 2020, the same year I scaled back Bamboula, my African import business (after 31 years). Living here is definitely a cross-cultural challenge!! Hope all is well.

Jasperdean Kobes

Jas, so nice to see I’m not the only ‘older folk’ as a regular reader of this blog . Just tried to send you a message on the Bamboula website CONTACT page and it didn’t work. I guess that is what you mean by ‘scaled back’. Now 21 years retired in Thailand… would love to get in touch somehow.