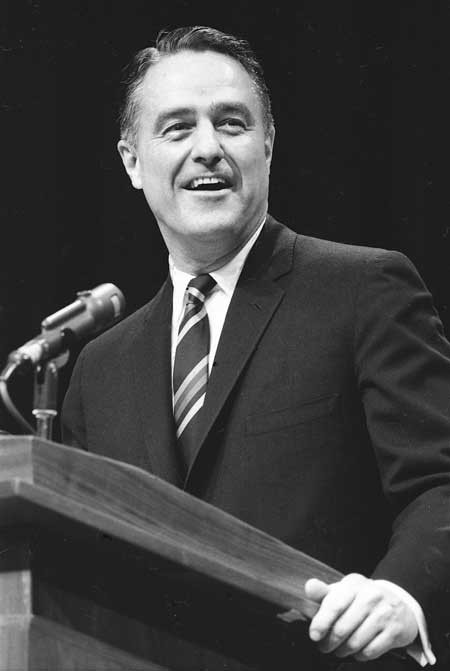

Sargent Shriver dies

TODAY the beloved architect and first Director of the Peace Corps Sargent Shriver died. Peace Corps Worldwide invites you to leave your comments and remembrances of Sarge.

For those living in the Washington, DC area, Peace Corps Headquarters has a book of condolences available for the public to sign for Shriver’s family. It is located just within the entrance to the building at 1111 20th Street, N.W.

(Photo by Rowland Scherman)

Sarge came to visit we Peace Corps Volunteers in Asmara, Ethiopia in 1963. At our meeting with him he stated his surprise that several street boys had approached him asking, “hey Sarge, give me five cents.” He was amazed to know that they recognized him. We had to let him know, there was a large US military installation there and the street boys used the term “sarge” to refer to any GI.

Shriverizing the Peace Corps

In the Peace Corps of the early sixties, to Shriverize an idea meant to enlarge it and apply greater imagination, and then speed up its execution. As an English major I had never heard the word, but as I learned the lingua franca of the new Peace Corps, this verb would change my life. A Midwestern Catholic boy, I had come of age with the presidency of John F. Kennedy and was a small part of the New Frontier as a Peace Corps Volunteer. And I was Shriverized by the man himself, R. Sargent Shriver.

In the summer of 1962, I left Midlothian, Illinois, and went to Washington, D.C., for Peace Corps training. That’s when I shook hands with President Kennedy and first met Sargent Shriver. I was a Kennedy Kid and proud of it, and like hundreds, and then thousands, of others, I was going off to change the world. And, yes, we really believed we would. We believed because we believed in Sarge Shriver. We revered him for being our connection to Kennedy and the New Frontier. But we loved him for himself.

If it hadn’t been for Shriver, there wouldn’t have been a Peace Corps. He took an idea, half-conceived by Jack Kennedy late one night in an impromptu campaign speech at the University of Michigan, and developed it into an agency that Time Magazine would call in 1961 the single greatest achievement of the new administration. And the reason it became such a big success — both instantly and even now, 50 years later — was because Sarge shriverized it.

From the very beginning, Shriver saw the Peace Corps as an idea whose time had come. He knew that Peace Corps could be bigger than its tiny budget, bigger than the number of people who actually served. He immediately understood it as an idea that, in 21st century terms, could go viral. He envisioned the idea of Peace Corps flying around the world; he saw that it could become one face of the United States, an image of peace to balance the competing cold-war, arms-race, imperialistic image of the U.S.

With his vision, Sarge took a relatively small initiative and Shriverized it — and he didn’t mind fighting with his brother-in-law, the president, in order to do so.

In the first days of his new administration, Kennedy wanted a smoothly run foreign policy. To that end, the advisors who crafted the set-up for him — John Kenneth Galbraith, Henry Labouisse, and Lincoln Gordon — created a new super-foreign-assistance agency called the Agency for International Development (AID) and tucked the Peace Corps into a tight little corner of it.

While that placement probably made sense on a foreign aid flip-chart, Shriver knew it would be a death blow in recruiting the kind of idealistic, non-business-as-usual types he wanted as Peace Corps Volunteers, and he told Kennedy and his aides as much.

Shriver’s warning was ignored by the White House, the State Department and the new AID. Gerard T. Rice in his book on the agency, The Bold Experiment, quotes Bill Moyers observing, “The employees of State and AID coveted the Peace Corps greedily. It was natural instinct; established bureaucracies do not like competition….”

So Shriver began to work the back rooms of the White House, and with the help of Moyers, a former aide to Lyndon Johnson, convinced the vice president to lobby the President into letting the Peace Corps have its freedom. But even as he agreed, Kennedy required that Shriver pay a price.

According to Harris Wofford in his 1980 book Of Kennedys and Kings, Kennedy told his sister Eunice, who was Shriver’s wife, words to this effect: “If Sarge doesn’t want me to have it in AID where I wanted it — let him go ahead and put the son of a bitch through Congress on his own.”

If Kennedy hoped that the daunting prospect of operating without presidential backing would force his brother-in-law to cave in, he was wrong. Shriver hand-sold the idea of a Peace Corps in the hallways and offices of Capitol Hill, one member at a time, says Wofford. His book tells the story of how a congressman, a member of the House Rules Committee, remembered Shriver: “One night I was leaving about seven-thirty and there was Shriver walking up and down the halls, looking into doors. He came in and talked to me. I still didn’t like the program but I was sold on Shriver — I voted for him.”

We all voted for Shriver, both then and now.

In these days of rancor in the halls of Congress we can only wish we had more legislators and officials who wore their hearts on their sleeves, as Sarge always did, and who knew how to Shriverize an idea whose time has come.

John

Below is a piece I wrote a few years ago — but it seems very fitting to share it today. I feel so privileged to have befriended my personal hero, Sargent Shriver. What a beautiful, global legacy he leaves behind in the creation and growth of the Peace Corps.

****

When I first met Sargent Shriver in the spring of 1994, I was a star struck new employee at Peace Corps Headquarters. On my first day of work, instead of sitting through one of those painfully dull HR overviews, I had the opportunity to hear the amazing Sargent Shriver speak to our team, as great fortune would have it. I was beyond excited because he had long been my personal hero.

During the course of his speech, he mentioned how proud he was of his children, particularly his son, Mark, who was making his first run for the Maryland House of Delegates.

I was a veteran of licking envelopes for the Clinton-Gore campaign while I was in law school, so I immediately sensed a “hook” by which I could meet my hero.

I worked my way to the front of the crowd after Sarge had finished speaking, and as he was the shaking hands of my equally star-struck colleagues, I blurted out that I would be honored to volunteer for his son’s campaign…every weekend until the election. Sarge smiled, took my newly minted Peace Corps business card and said that his son would be thrilled to have such a zealous volunteer on board.

Imagine my surprise when that Saturday, as I was mopping my kitchen floor in sweat pants, my phone rang. Sargent Shriver — Peace Corps founder, Ambassador, head of Special Olympics, father-in-law of The Terminator (!) — was calling for me. I nearly fainted! By the next weekend, I was wearing my “Mark K. Shriver for Maryland House of Delegates” t-shirt and canvassing the greater Montgomery County area with some college students from Mark’s alma mater, Holy Cross.

Fast forward to October 1994. The Shrivers were hosting a wonderful family day event at their Potomac home in honor of Mark’s campaign and as a way of thanking all of the people who had given their support.

There were probably a few hundred people at the event — friends of the candidate, volunteers and interested voters from the community. Because Sarge is a bit larger than life, some guests were a little bit star-struck, just as I had been upon meeting him for the first time. Most people would quietly edge up to him, quickly shake his hand (if that) and then excitedly scurry away.

But by the time this October event had rolled around, I was at ease around the man I called “Mr. Shriver.” I had logged hundreds of miles of pounding the pavement in support of his son’s candidacy. I had escorted the Shrivers on some of their neighborhood canvassing efforts (including some nerve-wracking stints as Mrs. Shriver’s campaign trail driver). I had eaten hot dogs in their kitchen. I had been Sarge’s official escort at a number of Peace Corps headquarters events. Though certainly no insider, I had endeared myself to Sarge because I showed loyalty to two things that meant very much to him: his family & the Peace Corps.

So on that fall day in 1994, I was pretty comfortable chatting Sarge up as hundreds of people milled around on the Shriver’s sprawling lawn.

Just then, a band started playing that Glenn Miller classic “In The Mood.” My feet started tapping. I don’t know what compelled me to do it, but I asked Sarge if he would like to dance with me. As no one was on the dance floor yet, he politely stalled.

“I don’t want to be the first one on an empty dance floor. I’m not a very good dancer.”

“Oh, c’mon, Mr. Shriver,” I pleaded.

No luck.

“C’mon, Mr. Shriver,” I pleaded some more. “Come show everyone some of those great moves you used when you were courting Mrs. Shriver.”

Then Sarge said to me, with a big twinkle in his eye:

“My dear, she will tell you that all of my best moves came OFF of the dance floor.”

(It turns out that he is a marvelous dancer, to boot!)

Kristen…you bring a smile to my memories of Sarge, our Director. Peace Corps was and always will be his…where would we be without his charm, talent…and strength to stand up for what he believed in? I was a young Volunteer being sent to Colombia in 1964…I didn´t know much, but I knew Sarge was our boss, and still is. I recall how he stood up to USAID when they wanted to place Peace Corps under their agency…they still do! And I remember when he stood up to the Secretary State after the Marines landed in the Dominican Republic and State wanted to evacuate the Volunteers out of the country…Sarge knowing the Rebels and Government troops trusted the Peace Corps Volunteers, said the Volunteer would stay and told the Secretary of State when informed that the Volunteers had to leave, Sarge said…¨No, Hell No!¨ And the Volunteers stayed much to the joy of the Dominicans! Thank you Sarge…you made a difference in my life and the lives of millions of individuals across this planet. I would never have met my beautiful Colombian bride Gloria, nor would our son Randy have been born in Colombia…you opened that door I went thru, and my life has not been the same. We love you Sarge! I Dedicate the first 50 years to you, our Director. Bob

Bob Arias

Peace Corps Response Volunteer/ Paraguay 2010-2011

Peace Corps Response Volunteer/Panama 2009-2010

RPCV/Colombia 1964-1966

Regrettably, I never had the opportunity to serve during Sarge’s tenure as Peace Corps director. I served from 1971-73 during which time Joe Blatchford directed ACTION. I heard him speak one time (I think it was during our in-country training in Togo) and he did an adequte job but he was no Sargent Shriver!!!

Mike Meyers,

Peace Corps Dahomey (Now–Benin), 1971-73

I am a current volunteer and never met Mr. Shriver, but I absolutely love the organization that he created. We are so lucky that he created such a wonderful and long lasting organization. Without a doubt all us would be very different people if we had not joined Peace Corps.

Danny Sherrod

Peace Corps Panama group 63

Peace Corps Suriname SUR 13

Sargent Shriver was the Director of the Peace Corps when I was a volunteer in Colombia (1964-66). He actually embodied the enthsiasm and energy we all felt wanting to do what we could. He was young, handsome, charning, and had a voice that emited sincerity and hope. I was proud to be one of his Volunteers.

Terry Kennedy

Gardena, California

My personal favorite story is that when Sarge came to Ethiopia to visit with us as the first group assigned there, His Imperial Majesty, Haile Selassie learned of his presence in country. As I have said before, the emperor was the reason that Peace Corps was there since his ministers felt that we would be a bunch of hippies and of little use.

The emporer wanted Shriver to come to the palace and be presented, as if he were an ambassador. But, Sarge had no “soup and fish” formal attire with which to make his presentation. The american ambassador lent Sarge his attire. However, given that the ambassador was much shorter than Sarge, a photo taken of him bowing to the emporer shows his white socks up to his ankles.

My personal rememberence was meeting him at one of the reunions and telling him that what I got out of the Peace Corps was a wife (Peru 7). I also showed off the pin that had been sent to all of us who served during his reign at the Peace Corps. It was comprised of two horizontal lines intersecting in the center symbalizing clasped hands; green in color to represent peace by Africans, on a white background representing peace to us. I still wear it on occasion with the greatest of pride.

Lastly, I thank God for Sarge and Harris Wofford convincing John Kennedy to contact Coretta King in Atlanta, and then informing all black leaders of his actions. I strongly believe that it was the black vote that made him president and prevented nuclear war with Russia over the missles in Cuba. I believe that Nixon would have pushed the button, given his hostile exchange with Kruschev at a mid-western fair. Nixon was quoted as saying that he should not have listened to his advisers and made a similar call to Ms. King. So to Sarge, who saved society from anhialation.

My memory of Shriver is from the days of training at University of New Mexico. That great expansion summer of 1963 saw hundreds of us on campus, training for Brazil, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia. My group was among the real second generation Peace Corps. Colombia I, the second group to hit the ground running in 1961, had just completed their service and many had returned to do our field training.

Shriver came out to New Mexico to greet the troops, so to speak, in late August. Instead of a small, admiring group, he found a crowded auditorium of “non -happy campers.” We had a lot of questions and many complaints. We did not like the five hours a week of Russian history and t hought the time could be better used. Specifically, the complaints were about the lack of specific technical training and the vagueness about what we would actually be doing. Shriver fielded the questions gamely, but he was obvious he was not expecting this kind of crowd.

I liked to think that it began to dawn on him that it wasn’t the State Department or the Republicans who were going to take his Peace Corps away, but us. We were already claiming ownership of “his” idea, and demanding answers. I hope he also realized that the success of a project happens when the people involved claim it as their own.

PS. When I received my service pin, it came in a narrow padded envelope. My first thought, “They want another specimen.” I was pleased to see the pin, even though I rarely wore ties. I had it made into a ring. I wore it with pride.

Sargent Shriver came to Columbia University less than three weeks after John Kennedy was assassinated. I was a senior and came to listen to his presentation. It was profoundly moving. For a 21 year old who had achieved very little, I was inspired to give something to my country to honor a 46 year president who had achieved so much.

I joined the Peace Corps and it changed my life. My two years in Tunisia opened my eyes to a new world. I became a diplomat and later a trade negotiator.

15 years ago Sargent Shriver showed up at a small reception hosted by my former Peace Corps Director. We met briefly and I told him about the impact of his speech at Columbia. He was delighted. We will all miss him

Lewis Cohen

Good article(s), John Coyne. Thanks. PS Please spell my credit correctly.