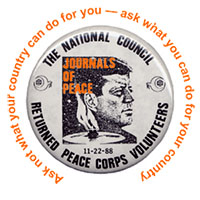

Journals of Peace — Patrick H. Hare (Honduras)

Journals of Peace

6:15 pm

ED CALLED WHEN I was gearing up for a business trip and a presentation, cleaning up my desk and my mind for the trip and leaning into it the way the plane would lean into the take-off the next day. Papers for the trip, getting cash, and polishing shoes hurried through my mind like a drive-thru meal.

When I knew Ed in the Peace Corps, we made time to talk. Most Volunteers did. Savings and loan co-ops, check dams for erosion-control, and raising money for sewers in my barrio had the same urgency as the trip I was going on now. But the landscape was different in Honduras, and lonely. There were hills with stunted corn and young rocks seeded together up the sides. The hills had trees on top. They were small, unfamiliar, cone-like hills, with green cowlicks.

The campesinos were unfamiliar too. They were very humble – muy humildes. In shapeless pants. Machetes hung on their thighs and on their souls.

When Volunteers got together, we needed to talk.

Ed was calling to say that Jim, another Peace Corps friend, had died. Jim had had leukemia and I hadn’t known.

My last memory of Jim is in a Chicago street. He took me out of a party of former Peace Corps Volunteers from Honduras to show me my old Volvo station wagon. It had been three years since I had sold it to him.

Jim had just bought new tires. He was proud that all the car needed were those new tires, and proud of the connection the car made between us. His chin always came forward and up a little with enthusiasm. The light yellow color of the Volvo sits in my mind, glowing softly against a late summer evening street.

It surprised me that Jim was dead.

Then Ed had another thing to tell me. He himself had been through six operations for lung cancer. He might not be at the service for Jim because he was going to a doctor at the Mayo Clinic for another operation. His future looked so similar to Jim’s it would have been odd not to tell me his news. I could hear in his voice his hatred of the risk he was taking. He hated his own fear of wearing his lungs on his sleeve.

Ed coughed over the phone and I asked whether that was the lung cancer. “No, it’s just a little pneumonia, possibly from the operations and the metal clips inside my chest. I’m getting over it.”

He ended up in Texas during Jim’s service. The Mayo doctor had said it wasn’t worth operating. Ed and his family had gone to Texas to talk to another specialist and be at the beach and with his brother who lived there.

A beaten copper Christ was mounted below the laminated rafters of the suburban church were Jim’s service was held in Chicago. Before the service his teenage nephews walked around the altar, checking that the Bible was ready for their readings. The shoulders of their shirts were round and tight from lifting weights.

Bill was at the service. Bill had been my roommate in the Peace Corps. We are close, but he and Jim had been more than close, had wives who were sisters, had lived near one another in Alabama. Bill hugged me, a man’s hug — un abrazo. The hugs are something the Hondurans taught us. We use them with pride, the way you drive a good car.

Going into the church, I realized that Bill would sit with his wife and with Jim’s family and I was wondering where to sit. I didn’t see people I knew. Then there was Sigrid, another friend from Honduras, and her smile was so familiar, like seeing family. I sat with her and with a Mexican friend of Jim’s who once bought dinner for a group of us.

After the service, we went to Jim’s brother’s house, and talked. Bill got up to get a beer. When he came back and sat down, I felt how much I missed him for those few minutes, and how much I wanted him at the table near me, like Sigrid, like family. Then I missed Jim, and I thought of Ed and his metal clips, and I wanted to cry.

•

Patrick-

Well said.

We still hold those close to us in our memories, even if they no longer walk this earth.

Charlie Ipcar

Ethiopia VI (1965-68)

Did Bill visit Sandra Mueller in El Salvador in 1967?