“Our Wonderful Cook, Aragash Haile” by Richard Lyman (Ethiopia)

Our Wonderful Cook, Aragash Haile

by Richard Lyman (Ethiopia 1962-64)

Marty Benjamin, John Stockton, Dallas Smith and I who shared a house in Gondar had the naïve notion that we were going to be self-sufficient and live without servants. Little did we realize that in Gondar servants had servants. It took us several months to put aside the quaint notion of complete independence and hire much-needed help. The fact that of the four of us only Dallas liked to cook should have been a red flag from the start. Within a week we opened a charge account at Ato Ghile Berhane’s “Ghile’s Store.”

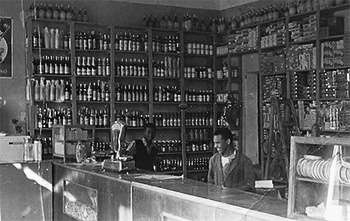

Ghile’s Store

It was a wide glass-fronted store just around the corner on the Asmara road from the post office. Behind a tall counter were two engaging young men who would retrieve what we wanted from the floor to ceiling shelves. Our bulk purchases like rice and pasta were poured into cones formed from used Swedish newspapers. We were intrigued by the sight of several boxes of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes on the top shelf off to the left side of the store. We never asked who requested them and the cereal was still there two years later. Each item we purchased was written down in our account book and once a month Marty, who acted as our household “minister of finance,” would settle the account.

I saved the two account books from those two years in Gondar and suspect that someday an anthropologist studying the eating habits of Peace Corps volunteers will find it a gold mine of information.

The Peace Corps supplied us with a kerosene refrigerator and a kerosene stove. A problem was that frequently there was a lengthy shortage of kerosene. The two sources were Besse & Co., an Empire-wide trading company, and the local AGIIP station. Whenever a supply would arrive by lorry from Asmara word would quickly spread and we would buy a number of tins.

At first, we ate a lot of sardines and canned corned beef. I have not in fifty years been tempted to eat another sardine. Because Dallas began to feel that we were taking advantage of him, which we were, the word was spread in the Gondar hospital community that we were in need of a cook. Betty Petti, a USAID nurse/instructor at the Hospital/Health College came to our aid. Because of her roots in Massachusetts, she spoke Italian and knew all the Italian families still living in Gondar. One family was in the process of returning to Italy and they had a wonderful cook named Aragash Haile. Betty arranged an interview with Aragash and we hired her on the spot.

Aragash’s father died in the early 1950s and her mother still lived in Asmara. Aragash spoke Italian, Amharic and Tigreanean. Living with Aragash in Gondar were her sister who was the cook for Signor Pigga, the Italian manager of HIM’s farm on the outskirts of Gondar and her brother who was a student in our school. The two daughters supported their mother and brother. Aragash prepared our meals five and a half days a week and was paid monthly.

Every morning on her way down from the Piazza she would bring fresh hard rolls for our breakfast and we would enjoy them with jam and pots of sweet tea. The other meals were left to Aragash’s creative talents. We thoroughly enjoyed her low fat/ low sugar Italian menu. Occasionally, when I passed the small Ethiopian Airlines storefront office near the Piazza I would step on their freight scale. Shortly before returning home I weighed in at 156 pounds. I attribute my excellent health during my two years in Gondar to Aragash’s fine care.

The American AID nurses at the Health College (Marjorie Paul, Berry Petti, Miss Van Buskirk, and Miss Garst) staged a party in our honor towards the end of our two years. They flew in all manner of cake mixes in the diplomatic pouch in order to treat us to a dessert night. We were so used to not eating sugar that we could only nibble small portions of their largess.

We discovered that if we especially praised one of Aragash’s meals it would reappear regularly on the weekly menu rotation. Every Wednesday we ate dorro (chicken) wat and injera and Saturday for lunch Aragash would prepare a large bowl of her famous sherro (chickpeas and spice) wat with injera which would last through the weekend. Of all the Ethiopian Restaurants I’ve visited over the last fifty years I have not tasted sherro that could match Aragash’s. Aragash used our account at Ghile’s Store plus her own sources for our food. For vegetables, she had access to Signor Pigga’s small storefront shop down the street from Ghile’s.

Ingera was delivered to our house by a young man in the morning. I have no idea where Aragash bought meat. Marty provided Aragash with funds for all these miscellaneous purchases. Dorro wat is a multi-spice sauce cooked for hours with usually a hard-boiled egg and a chicken drumstick in it. We knew it was good when our eyes would water, our lips would burn and our noses would run.

Because Aragash bought our ingera delivered fresh I had to go to our neighbor Mulgeta’s house to observe how it was cooked. I happened to be there one Sunday helping him with his garden when I wrote the following:

After helping Mulugeta with his garden I was treated to glasses of teg (honey mead) followed by gonfo, a wheat dough with a nest of milk and berberi spice in it. That was followed by warm milk and spoons of honey with the comb still in it. We spit the beeswax on the floor.

They were cooking ingera so I watched the technique. Three days before they had mixed water and teff flour in a jar and let it sit. When they were ready to cook the ingera they poured off the excess water then poured the teff batter onto a clay griddle. The griddle had been greased by rubbing six cabbage seeds on it. The ingera was allowed to cook on the griddle underneath a lid for three minutes. Ingera has the appearance of tripe. Because teff grain has no gluten, the dough does not rise like wheat bread. Instead it just bubbles and forms a flat honeycombed structure.

On April 5, 1963, I wrote the following:

We had a grand episode about Abebe who cooks for John and Peggy Davis. The new Canadian doctor associated with the Health College attempted to hire her away from the Davises by offering Abebe more money. This, of course, broke the unwritten law in Gondar that no foreigner hires away another’s servant. John and Peggy fought back with an offer of more money and English lessons. In addition, they called upon Abebe’s uncle and cousin to intercede. The fury of the counterattack took the Canadians by surprise so they gave up the fight.

Shaken by the struggle with the Canadians over Abebe we decided it was high time to buy Aragash the new dress that is customarily given to all new servants. We and the Davises took Abebe and Aragash to the arada (market) where the two chose material. We then accompanied them to a tailor who showed them an American catalog from which they selected the picture of the style they liked. Within days the tailor-produced two very attractive dresses.

In September Meskel is celebrated to commemorate the finding of the true cross. A large stick cross is erected near the Judgement tree which is on the way to the market. Both years we were invited to watch the two-day event from places of honor underneath the spreading tree. Priests, officials, and everyday people parade around the cross which is decorated with the yellow Meskel flowers. There is a lot of chanting and singing. Finally, on the second day, the cross is lighted on fire. There are local superstitions that if it falls in a certain direction good fortune will come to those farming and living in that direction. The first year the cross was slow to fall so it was given a gentle nudge in the right direction. Because gifts are given on this occasion we bought Aragash a new red sweater.

We could predict when Aragash was pleased because four days after giving her the sweater she served us one of her trademark “dolce” cakes. It was a pound cake shaped like one of our angel food cakes. To bake it she used a special Italian pan that circulated the heat on top of the kerosene stove so that it would bake without the use of an oven. When I asked for her recipe she had her brother write it down for me.

I added a few interpretive notes but I must confess I’ve never had the courage to try the recipe. Here’s hoping that an alert reader will perfect the recipe.

At Easter, during our final year, Aragash surprised Marty and me by giving each of us a sampler she had embroidered. Between two sprigs of flowers, it reads in Amharic “Exhabier qu ante gar yehun.” The translation is “God go with you.” It was a very touching gift.

Knowing we would be leaving Ethiopia in July 1964 we worked hard to find Aragash a new position. A German doctor desperately wanted her as his cook, however, Aragash had grown to like the American work schedule of Saturday afternoon and Sunday off plus paid time off when we were gone during school breaks at Christmas, Easter and the summer. She thus chose to cook for Gayle Bradshaw who arrived with the second Peace Corps group.

As we were loading up to leave for the airport for the last time we said our sad farewells to students, friends, and Aragash. We presented her with a new shama (dress and shawl). Back in Minnesota as winter was approaching I received a brief note from Aragash written by her brother. In it, she asked specifically about my Mother’s health. I sent Aragash back a picture of my Mother and Father (Richard B. and Mary Frances Lyman) and myself proudly holding “Aragash’s sampler.”

Richard Lyman (Ethiopia 1962–64) is from Excelsior, Minnesota and attended Carleton College where he received a B.S. in agricultural economics in 1961. At the university, he was a member of the honorary fraternities and chairman of the Student Center Board of Governors. Active in 4-H club work, he won several state awards in this field and was a member of a number of National 4-H Congresses. The father of three boys, he was a farmer for a number of years and then started a successful environmental Firestarter company.

Richard Lyman (Ethiopia 1962–64) is from Excelsior, Minnesota and attended Carleton College where he received a B.S. in agricultural economics in 1961. At the university, he was a member of the honorary fraternities and chairman of the Student Center Board of Governors. Active in 4-H club work, he won several state awards in this field and was a member of a number of National 4-H Congresses. The father of three boys, he was a farmer for a number of years and then started a successful environmental Firestarter company.

•

*This article was first published on International Policy Digest.

Absolutely delightful! Did it make John homesick? Thank you for sharing a crucial and entertaining part of your experience with us, Richard.

Leita Kaldi Davis

(Senegal 1993-96)

This memoir made me misty eyed thinking of our Ethiopian help: our four students who washed our dishes and had their own servant, the compound guard and most of all our “mamita”, Woyzero Taitu who took care of our son Thomas who was born in Addis during our second year there.

Suzanne Siegel 1962-64