“Oral Tradition in Writing” by Jeanne D’Haem (Somalia)

In the News —

by Jeanne D’Haem (Somalia 1968-70)

Somalis are known throughout East Africa for their beauty and for their poetry. In this oral tradition, poems are used to communicate, to share news and even to settle disputes. A poet insults another clan in a poem. For example, “You have mistaken boat-men and Christians for the Prophet.”

News and other communication had to be oral because the Somali language was not written even when I lived there in 1968. This was due to a dispute over what kind of letters should be used. Religious leaders wanted an Arabic alphabet, business people wanted a modern Latin one. When Siad Barre, a military dictator, took over the county in 1969, his goal was rapid modernization under communism. He sent a delegation to China where Chairman Mao held similar views. When Mao was informed about the dispute, he suggested the Latin script. He wanted the modern Latin alphabet used in China instead of the ancient pictograms. The Latin alphabet was formally adopted in 1972.

My village was an oral world. There were no Somali books in the school or newspapers. Most of the time I couldn’t understand everything being said, but I learned to watch the reactions of those who listened in the tea shops and around the charcoal braziers at night. Laughter, sighs, sorrow and angry reactions were clear to see in the facial expressions and helped me to understand what was said. Not being fluent in the language forces you to watch carefully picking up the nuances of meaning from reactions, not words. I have found watching the reactions of a listener a critical part of my writing.

When you give a story you wrote to a friend or your husband, they read it and typically say, “That was great. I liked it. ” Most people are not critics and they don’t want to damage a relationship either. This sort of feedback might be good for the ego, but it does not help you to improve your writing. I have tried watching people as they read my work. Unfortunately it makes people uncomfortable and they will go into another room or look at you reproachfully. When you are discrete about observing a reader, you can’t tell what they are laughing at or why they pause and look away for a moment. However, when you tell them your story, you can usually see exactly what they like and don’t like about it. For example, I told you that Siad Barre was a military dictator. Suppose I wondered if I should add; “ He came from a village named Dusa Mareb. In Somali that means “the fart that never ends.” If your listener laughs, it goes in the story.

When I first began to write, I got some very good advice from an author. She told me that writing is hard work. It takes an immense amount of time and effort. “You need to respect how much work goes into writing. Don’t waste your time working on something that others are not interested in reading about. If your mother is not interested in what you write, it is very possible that a publisher won’t be either. You will quickly get discouraged.” She said I needed to tell my stories first and watch carefully how the listener responded. “If they excuse themselves to get a drink, maybe that isn’t such a good topic to write about.”

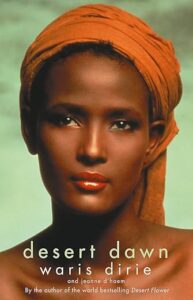

My second book was written with Waris Dirie, a Somali model who could not read or write. Every other week we would meet and she would ramble on about her problems into my tape recorder. She had never read a book and didn’t understand how it might work. I despaired of ever making a cohesive series of chapters. After a week or so we would meet again and I would read what I had written back to her, often in a restaurant. One day, after I read a few pages to Waris, I looked up to find that the entire restaurant had gone silent and was carefully listening to what I was reading. Even the waiters were standing nearby. This gave me the confidence to finish the book which became a best seller in Europe.

My second book was written with Waris Dirie, a Somali model who could not read or write. Every other week we would meet and she would ramble on about her problems into my tape recorder. She had never read a book and didn’t understand how it might work. I despaired of ever making a cohesive series of chapters. After a week or so we would meet again and I would read what I had written back to her, often in a restaurant. One day, after I read a few pages to Waris, I looked up to find that the entire restaurant had gone silent and was carefully listening to what I was reading. Even the waiters were standing nearby. This gave me the confidence to finish the book which became a best seller in Europe.

Fashion model, UN ambassador, and courageous spirit, Waris Dirie is a remarkable woman. Born into a family of tribal desert nomads in Somalia, she told her story in the worldwide bestseller Desert Dawn: enduring female circumcision at the age of 5; running away through the desert at 12 to escape an arranged marriage; being discovered by photographer Terence Donovan as she worked as a cleaner in London; and becoming a top fashion model. Although she fled Somalia, she never forgot the country or the family that shaped her. Desert Dawn is Waris Dirie’s profoundly moving account of her return to her homeland. As an international model, Waris Dirie was the face of Revlon. In 1997, as part of its campaign to eliminate female genital mutilation, the United Nations appointed her Special Ambassador for Women’s Rights in Africa. She now lives in New York with her son.

Jeanne D’Haem (Somalia 1968-70) Ph.D. is an associate professor of Special Education and Counselling at William Paterson University. Her career in education began as a Peace Corps volunteer in Somalia, East Africa. She was a director of special services and a special education teacher for over thirty years and lectures widely on issues in special education. She has published two prize-winning books and numerous journal articles. The Last Camel, (1997) published by The Red Sea Press, Inc. won the Paul Cowan prize for non-fiction. Desert Dawn with Waris Dirie (2001) has been translated into over twenty languages and was on the best seller list in Germany for over a year where it was awarded the Corine prize for non-fiction.

•

Desert Dawn

Waris Dirie and Jeanne D’Haem (Somalia 1968-70)

Viragouk Publisher

240 pages

$14.95 (Paperback)

Bravo Jeanne. We weren’t in Somalia together for very long but I do remember you. I will

certainly catch up with your writings right away. Bill Donohoe (Staff, 66-68).

0