Marjorie Michelmore Peace Corps, Post IX (Nigeria)

As for Marjorie. She returned to Peace Corps HQ with Ruth Olson and Tim Adams and went to work with Betty Harris and Sally Bowles to put out the first issue of The Peace Corps Volunteer. It was, of course, an appropriate job, as Coates Redmon states it in her book on the early days of the agency, Come As You Are: The Peace Corps Story, since Marjorie was the first returned Volunteers.

In a memorandum to Sargent Shriver–attached to an Evaluation Report on Morocco (1963) done by Ken Love–and written by the legendary early Peace Corps Director of Evaluations, Charlie Peters, Charlie wrote, “Marjorie was as sensitive and as intelligent a Volunteer as we ever had in the Peace Corps.” The lesson that was learned by the Peace Corps was that “even the best young people can be damned silly at times.”

According to Gerard T. Rice in his book entitled, The Bold Experiment: JFK’s Peace Corps, “The President’s personal support helped the Peace Corps weather its first storm.” Kennedy’s handwritten note to Michaelmore said, “We are strongly behind you and hope you will continue to serve in the Peace Corps.”

At the Peace Corps HQ the feeling was that the agency had weathered this early storm. Warren Wiggins would write, “The greatest thing that could have happened to the Peace Corps in the beginning with a postcard from a Volunteer mentioning that people pee in the streets in Nigeria. It was like a vaccination…..Never again would a major newspaper, under the worst of conditions, streamed anything negative about the Peace Corps. Since then, the Peace Corps has had rape, manslaughter, bigamy, disappearances, Volunteers going insane, meddling in local politics, being eaten by crocodiles, but never again did it get a bad play in national news. The vaccination took; we were immune.”

The PCVs stayed and the Peace Corps program continued and grew in Nigeria. As for Marjorie? Well, early in ’62 she left the Peace Corps and married Frank Heffron

Several years ago I located Marjorie and asked her if wanted to write her account for our website. Marjorie wrote back saying, ‘thanks, but no.’

She did, however, tell her story in an interview that appeared in the Smith College’s Quarterly Magazine in 2011.

The following is the Smith’s interview, the first and only time she has spoken at length about her ordeal.

What made you want to join the Peace Corps?

It started with Kennedy’s inaugural address in January 1961: “Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.” I responded to that. I really wanted to be part of that whole dream. And I was very excited and proud when I was selected to be in the first group to Nigeria.

You were still in training at the University of Ibadan when you wrote the infamous postcard.

I have blocked it pretty much, so I don’t remember the text, but I remember that it was stupid and insulting. There was a leftist group on campus who thought that the Peace Corps was a front for the CIA, and they were ready to seize the first chance they could get to embarrass the Peace Corps. I either dropped the postcard or it was taken out of the mailbox. I have no idea how it was found. The students gathered, and there was a riot, or certainly an uprising. There were torches, I remember, and shouting, but I didn’t see much of it because people on the staff came and got me away.

What happened next?

There was a possibility of violence; the students were making a lot of noise. I was moved to safe places for a couple days. Then I was taken to [Nigerian Governor-General Nnamdi] Azikiwe. I apologized, and he was very gracious about it. Then I left in a plane. It was all very cloak-and-dagger. I came to New York via Rome and London, and in each place there were large press presences. By the time I got to New York, the press was pretty huge. I just had to deal with it.

It was in London that you received a cable from President Kennedy.

I’ll read it to you. It’s dated October 18, 1961. It says, “Dear Miss Michelmore, I want you to know that we are most appreciative of your steadfastness in recent days. We are strongly behind you and hope that you will continue to serve in the Peace Corps. Sincerely, John F. Kennedy.”

What did his support mean to you?

It really mattered, because I was devastated. I felt that I had let down the president; I possibly thought I might have wrecked the whole Peace Corps idea, and I let down my friends in the group and actually put them in some jeopardy. I’d been through quite a lot of stuff. So for him to say “we’re strongly behind you” was just amazing.

How have you coped?

I never talked about it—ever—to anybody, even my best friends. I never knew whether they knew about it, because of course my name had changed. So when I went to a new town and made friends, I obviously didn’t ever bring it up. From the beginning I felt it was a stupid and insulting thing for me to do, and I was ashamed of it.

Have you been able to forgive yourself?

Oh, I live with some regrets.

What remains of your Peace Corps days?

Two boxes. My mother kept everything—all the letters that came from all over the place, and the press stuff. I don’t think I want to go through those cartons. I’ve tried a couple times, because we’ve been carting them around, house to house. But I start reading the letters from angry people—there are a lot of wonderful letters in there, too—and it brings it all back, and I close the cartons.

Clarice (Reese) Heller Berman ’61 told me she felt only sympathy for you because “it was something anybody could have done.” Is this how most of your fellow volunteers reacted?

Yes, it was, but I didn’t know that until I finally went to the fortieth reunion of Nigeria I ten years ago. Reese told me that; other people told me that. It was just so warm and welcoming. That healed a lot of the pain I’ve always felt about the whole thing.

In closing one last note on Margery (Marjorie) Michelmore Heffron. She earned a master of arts degree from Columbia

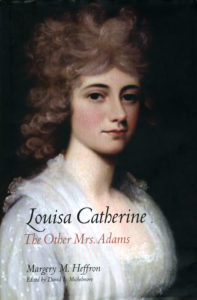

Univeristy and worked for Harvard University as director for media relations before becoming an associate vice president for university relations at Binghamton University. When she retired she and her husband returned to live in Exeter for the last 12 years of her life. Until her death from cancer in 2011 she continued to work as a freelance writer and editor and wrote a biography of Louisa Catherine Adams, wife of the sixth U.S. president published by Yale University shortly after her death. In previous articles I have written about Marjorie, I said she was certainly the most famous Peace Corps Volunteer. I continue to think so.

In previous articles I have written about Marjorie, I said she was certainly the most famous Peace Corps Volunteer. I continue to think so.

HEFFRON, Margery M. Age 73, of Exeter, N.H. on Friday, Dec. 9 2011 of cancer. Until her death, she was at work on a biography of Louisa Catherine Adams, wife of the sixth U.S. president. She was a graduate of Smith College and earned a master of arts degree from Columbia University. She was press secretary to Rep. Edward J. Markey, 1979-80; associate director for media relations at the Harvard University News Office, 1981-89; and associate vice president for university relations at Binghamton University (SUNY), 1989-95. A native of Foxboro and a longtime resident of Westwood, she is survived by her husband of 49 years, Frank H. Heffron; daughter Anne Heffron (Chris) Sigler of Palo Alto, Calif.; sons John Heffron of Providence, R.I., and Samuel (Ashley) Heffron of Kittery Point, ME.; three grandchildren: Keats Iwanaga of Los Gatos and Palo Alto, Calif.; and William and Phineas Heffron of Kittery Point, ME. Services will be held at 11 a.m. Saturday, Dec. 17, at Christ Church Episcopal, 43 Pine St., Exeter N.H. Contributions in her memory can be made to the Exeter Public Library or Smith College for the Class of 1960 Memorial Fund.

HEFFRON, Margery M. Age 73, of Exeter, N.H. on Friday, Dec. 9 2011 of cancer. Until her death, she was at work on a biography of Louisa Catherine Adams, wife of the sixth U.S. president. She was a graduate of Smith College and earned a master of arts degree from Columbia University. She was press secretary to Rep. Edward J. Markey, 1979-80; associate director for media relations at the Harvard University News Office, 1981-89; and associate vice president for university relations at Binghamton University (SUNY), 1989-95. A native of Foxboro and a longtime resident of Westwood, she is survived by her husband of 49 years, Frank H. Heffron; daughter Anne Heffron (Chris) Sigler of Palo Alto, Calif.; sons John Heffron of Providence, R.I., and Samuel (Ashley) Heffron of Kittery Point, ME.; three grandchildren: Keats Iwanaga of Los Gatos and Palo Alto, Calif.; and William and Phineas Heffron of Kittery Point, ME. Services will be held at 11 a.m. Saturday, Dec. 17, at Christ Church Episcopal, 43 Pine St., Exeter N.H. Contributions in her memory can be made to the Exeter Public Library or Smith College for the Class of 1960 Memorial Fund.

No comments yet.

Add your comment