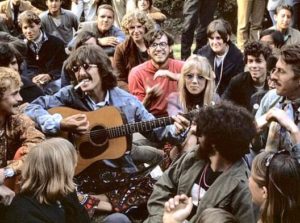

Make Love Not War . . . Will Siegel (Ethiopia) writes Haight Ashbury novel

Will Siegel

Will Siegel (Ethiopia 1962-64) went to San Francisco after his Peace Corps years and much of his new novel is set during the “summer of love” in Haight Ashbury. Peace Corps Writers will be publishing Will’s Last Journey Home — A Novel of the 1960s, next year.

Here is a chapter from his forthcoming book. As Will describes it:

This is a chapter about midway through my novel.

Gil, the main character, returned from the Peace Corps in Ethiopia, is now in graduate school and after about a year and a half, (in the spring 1965) he brings his girlfriend, Suzanne, to meet his new hippie friends. He is trying to please them both, though he sometimes resents that the apartment, near the Haight Ashbury section of San Francisco was taken over by this hippie cohort of his roommate, Franco.

There is another RPCV in the room, Busby, who has completely disavowed his Peace Corps experience by declaring his former self dead and he is starting over.

Meanwhile, Gil is trying to make peace with himself and defend the group’s anti-war views to Suzanne. This dichotomy furthers the split that is beginning to overwhelm Gil and his view of the world as the Vietnam war begins to take over the national dialogue.

•

AN EGG’S AN EGG FOR AYE THAT

by William Siegel

A cool and fragrant spring evening as Gil’s hippie clan gathers in the slant-roof attic living room of Cave 7.

Gil’s come to his senses over these strange people. He’s given up his gripes to Franco — or anyone — about this house of strangers, nor does he try to stem its flow and growth. Tension fades as Gil’s tolerance builds affection. He accepts Lenny’s post-midnight footsteps on the thin carpeted stairs. He finds he cares about Libby’s welfare and worries about her back room coughing flares. Franco’s broken agreements and flitting from house to house bother him no more. Bucky treats Gil as a refugee from a boarding school. So what? Gil smiles and chats about the decline and fall of the American empire. Busby, no longer Noonan, fallen out of their Ethiopian adventure, warps into another paranoid dope dealer. Gil has accepted his home and come to terms on Steiner Street. “Let ’em all go to hell but Cave 7,” he roars silent and chuckles across his mind’s eye view of this world. Gil thinks himself a liberal fellow, now, accepted into his world. Gil still jumps when someone walks into his room, becomes flustered when he can’t find a pen, screams inside when Bucky is boorish at the table throwing his napkin in the bowl and walking out of the kitchen without a thought to help clean up. But Gil pushes these frustrations down his esophagus, past his breastplate, down further into the nerves surrounding his gut where they form a low level growl of electric current waiting to leap out. Though, in fact, Gil uses much energy to keep these seeping emotions down where they burn dully among the smoky canticles of his unconscious; he does not recognize this inner song and so he fights the false war, but don’t tell him that or he will walk out of the room.

Wayne sleeps in the kitchen, Lester behind the couch. Gil loves them both. Wayne practices guitar runs by the hour, which never become unbearable. He cooks now as well, often bakes bread or boils large pots of brown rice and vegetables that feed their numbers. Gil’s angel Lester their electrical genius remains their only earner and steady supporter of food and rent, a lad always pleasant, interested in others, never alarmed and ever retiring about himself. Gil makes a separate peace with these souls. No, he could not get along with his God-given Midwestern family and its beliefs and customs; but now he’s joined a family he can bond with and face the world. He may drop out of grad school and join the real planet. A degree offers him nothing. He bides his time. He might move to the country with Suzanne and raise chickens on a backwoods ranch, when he has beaten the draft. In his young life dropping out might prove prudent. He begins to accept “cool,” “far out” and “groovy” as his inner state. These thoughts flit through his recent remade mind as the commune assembles for their modern hippie family evening at home. Suzanne and Gil sit on the living room’s worn Persian rug and watch their single-channel TV.

Helicopter locusts land on rice paddies and burn the jungles of Vietnam. Foot soldiers in full battle gear leap and charge into villages of thatched huts as North Vietnamese flee in horror. Toothless old women gape and old men in baggy pants and pajama shirts quake while rude soldiers push them aside, search for arms and the enemy. Weapons chatter with bombs bursting in air. Serious young news correspondents, short-haired and handsome in spotless jungle camouflage shirts, precise in their toothy objectivity, report from the scorched outposts of Southeast Asia as the sun sets beyond San Francisco’s fading strawberry sky.

Eucalyptus and pine scents from Alamo Park drift in through the open skylight. The smells mingle with two fresh loaves of Wayne’s macrobiotic bread that sit on the coffee table by an open jar of apple butter. Lenny passes a large joint. High on speed Bucky trudges in from the back bedroom, sweating and red-faced. He sits and looks grateful for people. Libby on the floor looks devilish in search of something in the room she might paint or decorate. Paul Butterfield, blue and sassy, spins on the record player.

Lenny, on his knees, is cleaning grass. His fingers crush the sticky buds into the lid of a shoe-box. He slopes the lid, pushing the leaves to the top with an open matchbook cover, winnowing the golden brown flakes while the seeds roll to the bottom making a pleasant drumming sound. The pile of fresh weed, acrid and faintly musty, swells their hearts as keen as any flag.

Wayne taps his foot to the music, cuts thick slices of bread and passes them around. He brings surprising strength to the house. Upright as Whitman, his bearing puts them all on best behavior.

Lester hangs in a corner and rewires a hi-fi, looking up from time to time, his smile everlasting and good-hearted.

Libby chooses to make over the TV cabinet with psychedelic flowers of orange and blue and gold, and lets her brush lick tongues of flame onto the tube’s four corners.

Lester laughs. “My TV’s gone awful fancy.”

Libby’s return smile offers wry crinkles.

Gil sprawls on the rug with Suzanne wearing a flowery skirt over dancer’s leotards. They spend most nights at her place. But tonight he reveals her to the family. She passes on the marijuana. Gil offers her the joint each round but Catholic Suzanne waves it on with a papal blessing. She lets him know of her unease with drugs and hippies and at every chance calls his friends “zippies” and “drippies.” She tells him: “You’re a grad student and very, very different from these castoffs. You and I know the world has more to offer than these gaudy little druggies ever dream of.”

Gil assumes these are the very troublemakers that will change the world and reckons Suzanne needs this first contact with his friends and the culture crystallizing around them before she shares his own gloomy admiration. His friends he explains to her, hope to extend the ethic of “smoke and cool” to embrace the world. “We break bread and new ground for the war-weary slaves of modern society,” Gil says. He coughs at her ignorance. “We make no judgments. sweetheart. We give everyone space to do their own thing. Our spiritual outlook embraces the world. We refuse to suffer the same guilt our parents suffer. Watch us stuff peace and freedom down the throats of the planet’s rednecks.”

“These people are not grounded,” Suzanne says. “Where they stand, there’s no ground. Sweetheart.”

“Dangerous accusations for the child of fly boys,” he tells her back. “Just like your old man, we’re redefining a new ground, honey.”

Bucky, burly and contrary, now unfurls a page of his free verse about the fall of the American empire and the coming wipe out of the hippies of Haight Street, and about the final radiation of mankind in general.

Breathless Lester, half-hidden behind wires and switches, after some coaxing, tells of his childhood in upstate New York, where he turned out to be the youngest son in an interracial marriage which gave birth to eight white children and a lone black Lester. A story listened to in hushed silence even through the comical parts.

Laurence Olivier passes through the room, his eyes awash, dark and brooding, looking in need of sleep and a ticket out.

Lenny, secretive and opaque, unfolds childhood horror tales of friends who run away from home and come back with an arm chopped off by a railroad car or been kidnapped and sold to gypsy caravans. He adds, “And it’s all the righteous truth, man.”

Busby shows up in a trench coat, jeans and cowboy boots, red ponytail dangling from his slouch hat, and carries a new suitcase. His twins follow him up the winding staircase.

“Man, what is this, a hippie convention?”

Moonstroke and Weebie, more airy and drug-drenched than before, shuck long velvet coats to show off the new fad of dark stockings and miniskirts. A spangled vest covers Moonstroke’s dark see-through blouse. Weebie in a ruffled tuxedo shirt with ruby studs over her own see-through blouse keeps her voice more reserved than Moonstroke’s frenetic chatter. Weebie may lack her sister’s glow but gives off a strong cool charm.

Busby peers down the stairwell to check on shadows.

“I swear a car full of pigs tailed us from Oakland. I drove around North Beach for half an hour to give ’em the slip.”

He peers from face to face through the smoke and makes sure he knows everyone.

The twins sandwich Wayne between them on the vinyl couch. He wiggles his ass and notes that both are braless behind their little vests.

“I got to get some refuge,” Busby tells Gil in his bedroom and checks the park below. His voice thickens. “Hey man, there’s people loitering in the park.”

“It’s a park. People loiter.”

“I gotta stash this,” he says of his suitcase and heads for the usual closet. In the living room he sits by Gil on the floor, pulls out a cigar-size joint and says to Suzanne,

“Let’s try some of this. But I warn you stay seated for the five or ten minutes after your first toke.” Busby grins showing the space between his two front teeth, a smile that Gil remembers from a thousand years ago in Ethiopia.

The Steiner St. house has become Busby’s dope warehouse. Despite his grandstanding, Gil’s grateful for his old friend’s generosity. Gil covers over his resentment that Busby’s taking advantage and putting them all in danger. But Gil buries his alarm and fright. If they get burned they’ll deal with it using Franco’s philosophy, “Whatever happens, happens.”

Suzanne whispers. “He’s so kooky, I can’t believe he’s your friend.” She glares at the twins, smoking in tandem, vests loose and skirts high.

“Hey, Generalissimo,” Gil calls across to Franco who crouches in the corner, a hostage to the pungent cloud of grass. “Let’s hear from Denmark’s Paisley Prince,”

Hearing his name, Franco recovers himself from some faraway place. He blinks and looks over with a puzzled smile.

“Hey Lord Olivier,” Bucky says. “Where’s the prince.”

After a moment, Franco stands, exhaling smoke through his nostrils.

“Ghosts of my father’s war call me. I am here.” Franco in an off-center English accent pauses a dramatic beat. “Omelet, Bad Egg of Denmark, the Great Pretender to the throne.” Placing his booted-foot on the corner of the coffee table, raising his hand, he presents his own Hamlet.

“This day, my father’s ghost with grave pro-pri-ety has come upon me crying, accusing youth unworthy of our Great Society. Unworthy to follow the traditions of Hannibal and Alexander the Great, you wretched weak descendants of Greek warrior states. Pathetic sons to Rome’s legions. Inferior to the Kings of Spain who defeated the Moors and tended the Inquisition. Miserable progeny of Russian Czars and Austro-Hungarian princes. You coward sons of the brave soldiers who defended our rights from exploding Kamikazes, and annihilated the anal fixations of Hitler’s Nazis.

“What duties have you spurned ingrates, refusing a decent day’s work and a piece of the action in future stakes. This ghost reminds that you obsess with earnest politicians, breeding canker sores of fantastic suspicions. When you cry peace, it reeks of disgrace.

“You mock the plain good sense of your betters, while binding yourself in youth’s ignorant fetters. Indeed, the officers of authority see quite well the youth of this country camped before the gates of Hell.

“However, told I this ghost, do not fear youth with its sweet breath. Fear instead impotent old men obsessed, gloried in destruction and the weapons of death. Go stuff thy own revenge.

“These mighty tools of combat already did exist, bequeathed as Christmas toys and birthday gifts, brought to our tender childhood play to wean us from our mother’s breast and senses. We cut our teeth on metal guns and barbed wire fences.

“Now I slay my father’s ghost, turning this fight upon its rightful hosts. Wherefore I propose, we take these aging warmongers, imprison them on Maggie’s farm and let them hold congress. Give them planes and bombs and rifles. Let these politicians and Generals choose up sides to murder each other over trifles.”

Wagging his finger, Franco looks around the room. “With all due respect to my father’s charter, who called me Omelet in exalted honor, me thinks this dripping egg on the face of Denmark’s elders smells rotten?”

“Right on,” Gil cries.

Lenny looks up from the shoe box, “Far out, man.”

“We’ll put ’em all up there,” Bucky chimes in, “Johnson, McNamara, and Ho Chi Min. Chairman Mau Mau and Khrushchev. The whole lot of do-badders and mad-hatters.”

“Don’t forget the factories that make tanks and mortars,” Libby says, applying paint to the TV, “and the ones that make napalm.”

“All of them.” Franco says, asserting his accent. “The military-industrial complex and the Freudian-inferiority complex – all these politicians, and assorted warriors who make their fortunes from the blood of our brothers. We’ll take ’em prisoner and run their ass up the flagpole. The whole a gang of the old farts over thirty.”

“Far out!” Lenny pours the clean grass into a large baggie. He moves over to Libby, now painting the TV and picks up a brush.

“Here, here. Hail to the chief.” The audience joins amid claps all around.

Franco sits down, exhilarated.

“Right on!” Gil cries. Suzanne kicks him.

“Far out!” Lenny says and looks up, so pleased.

And Busby’s pot at last zonks Franco off his feet and onto the rug.

Bucky grins. “Hail Franco! Make the world safe for bureaucracy.”

Suzanne grabs Franco’s arm. “What about our boys dying for you, you bastards? And for all of you stoned pinheads making a game of war. You all want to make us out the bad guys. But what about those foreign butchers? Should they go free?”

Shame at opening herself to Gil’s doper buddies brings Suzanne to tears.

Gil tries to hold her but she shakes off his hands and fights her sobs with all her strength. Guilt fills Gil as he watches her back heave in the silent room. Still, his pride bonds with the righteous rage of his confederates.

Gasping, she rises onto her elbows.

“What gets me is…is that you don’t care about our boys, the ones we went to school with, who are laying down their lives.” She screams, “What’s going on with you people? How can you live in this stinking smoke and talk like children who don’t know any better? People I know are dying so you can do whatever you please. When do you talk about that?” She closes her mouth and looks past Gil to Franco.

Franco gives off a quiet grin, “Wow! What a grip, and she talks, too.”

Gil, caught in the middle, sighs and wants to protect her but he doesn’t want to care anymore. He is embarrassed by her outburst. He wants to live by the hippie command — Cool at any cost, man. This isn’t cool. Your Suzanne can’t handle it.

Everyone looks away. Gil tries to wrap his arms around Suzanne but again she shakes him off.

“This war is a TV joke,” Gil says to her back.

She wriggles up to sit on the floor. “A joke? What’s wrong with you? First you shout to heaven against napalm and then you say it’s a TV farce?”

“I mean it’s a mercenary war.”

“Oh, really? You don’t want me to cry because your dope fiend friends won’t like me. These, these cowards! All of your are afraid to fight and you want him to join you all. Well, you people have terrified Gil! You’ve sucked him in until he’s frightened of you all! His mind’s so twisted living here. He’ll squander our love for you dope-smoking morons.”

Silence floats about the room, crushing the smoke.

Suzanne gazes blind at the TV tube where Libby has just painted “FUCK YOU.” in red, white and blue.

Wayne stands up. “It’s been a righteous evening.” He nods at the TV. “We’ll get those mothers in the end.” He grins and walks toward his sack in the kitchen.

Libby puts her paints away. Lenny wipes the brushes with a piece of cloth.

Franco leaves for Lorraine’s.

Busby, after looking out the front window and the back window, motions his sisters in tow to follow down the curving staircase.

Suzanne goes into Gil’s bedroom. He’s afraid she’ll get her wrap and go home.

After a moment he follows and leads her to his mattress.

Her knees give way and she curls onto the bed facing the wall. Her back shudders. Gil strokes her shoulder.

“Now your friends won’t like me,” she tells the wall.

“I like you.”

“How can you like me?”

“Oh, they think you’re very courageous . . . because you proved it right here in enemy territory. If I had a medal I give it to you.”

“Oh, keep quiet. And hold me.”

They lie together but soon Gil is lost in less complicated times, in Ethiopia, with his Peace Corps buddies, over quarts of Melotti beer and injera and wot, they talked about their work and less about politics than how to build schools and teach essay writing. How to get better textbooks. They worked for change inside the system.

Now, it seems, every thing’s upside down and turned to greed and ignorance and tens of thousands slog toward death in Vietnam. It’s all wrong today. Not like his father’s war. This is a mercenary war, fought for the wealthy. But Suzanne doesn’t grasp it, can’t think it through. He won’t be cannon fodder. He rubs her arm as she goes under. How can Kennedy help as the issues fog over? Gil longs for his hero’s approval. Should he stay clean and run with the straight arrows? Or has he pissed that away? He’d never get into law school or admitted to the bar or become a civil rights lawyer. Or what if he had to go on the run for some civil disruption? How would she cope, being with a hunted fugitive? The shame to her family. Maybe they could go to St. Louis or Chicago, move into a clean neighborhood, find a stable job. But as what?

Gil moves to light a cigarette as Suzanne wakes and turns to him in shadow and moonlight. Pale green eyes bore into him.

“You’re a drug addict and clumsy and can’t dance. You live with riff raff. You stand up for everything my family and I are against. You’re a coward and an intellectual bully and a fraud as a citizen and afraid to fight for your country. You fear you will lose me. Somehow I still love you and even find you wonderful for some reason way beyond my depth.”

“It’s pretty clear then. I should be taken out and shot. And you should do it.”

“See? That’s why I love you.”

“Because I’m a smartass?”

“No. Because you’re a hopeless little boy in a great big world and need me.”

What great writing! And so true! Did I get it right; this is a chapter from the book – Last Journey Home — A Novel of the 1960s – which is scheduled to be published next year?

Yes, you got it right.

This brings back a flood of memories. As “The Haight” was folding, large numbers looked for something of substance, thinking of a “return to the land”. Arid New Mexico wasn’t the best place for agriculture, but they came, anyway. Their communities, now long gone, resonated with names like “New Buffalo”, “Morningstar”, “Taos”, “Placitas”. Later many would move eastward to their agricultural commune called simply “The Farm”. The film “Easy Rider”, with Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper was filmed in part at Morningstar. Hopper found meaning in this country, and today is buried in the Campo Santo, at Ranchos, south of Taos.

It was here in New Mexico that the ardently anti-war Hippies met the first waves of totally bummed out returnees from the Vietnam War. The two groups seemed to have an affinity (incl a lot of pot, and lesser LSD). A reality that seems missed by most historians of that era. The soldiers and the war protesters were essentially different faces of a single group. A lot of Peace Corps returnees similarly joined — usually maintaining some distance.

Further east of Taos, a bereaved parent set aside a track of land near Angel Fire in memory of his son, who died in Vietnam. It would become an annual Mecca for platoons of motorcyling ex-GIs from all over the Western states, equally bummed out but in a different way. A small chapel was built, and hardly a week went by that there wasn’t the family of a deceased veteran, seen kneeling, and praying. There was a basket there, always full of military medals left behind.

To this day I’m amazed that America actually survived it. But some say it didn’t — at least as it once was. It’s been said that America’s innocence and idealism died in the rice paddies of Vietnam, and thereafter only people like Gen Colin Powell, and Washington politicians would talk about “American Exceptionalism” For everybody else, it was anything but.

I had been drafted following my return from the Peace Corps, and still remember, after finishing at Fort Jackson, visiting my girlfriend and family. War protesters were everywhere in Washington, and I remember, being in uniform, being cursed and pelted with tomatoes. I remember in one instance, I had temporarily stopped at a bus stop to clean some of the tomatoes off the windows of my girlfriend’s car. This cop came along, utterly indifferent, and told me to move on. I remember thinking that if this ass hole had ever been in Vietnam, his own men would have seen to it he never came back.

And so, returning to native New Mexico, it was almost like an escape from America. There aren’t so many visitors anymore to the little memorial chapel near Angel Fire. Passing Morningstar on the way there, I always stop at the little chapel, and wonder how America ever survived it. Due to it’s popularity, and perhaps feeling a little marginalized, the Dept of Defense took over maintenance of the memorial site from the owner many years ago. One of the first things they did, was get rid of the basket of military medals left there. Sanitizing the place, and revising history a bit.

The Hippie communes are long gone, but many of the inhabitants are still here, leading more conventional lives. I meet one now and then. People often ask me why i advocate that the Peace Corps be returned to it’s original independent identity (effectively killed by people we trusted), and made an expression of the American People, and NOT a function of the US Gov’t. Some of my questioners wonder what is the difference. Nobody from back in the 1960s and -70s asks why. They instinctively understand.

Thanks for your kind words Joanne. I hope you will read the novel when it comes out.

John, my brother who lived in the Bay area for some time, moved to Santa Fe a long time ago and has always felt at home there.

Regards,

Will

Hi Will, Hope you’re still checking this page. If you happen to be visiting your brother in Santa Fe, contact me (no. in the phone book) and a breakfast at Harry’s Roadhouse is on me. Great chile fare. Or brother alone would be fine.

Harry’s is one of our relics of the Dust Bowl migration days, once a gas station and diner along the earliest alignment of historic US 66. Old timers with a sense of imagination, say that late at night, when everything is still, sometimes you will see a row of model T Fords, with mattresses piled on top, and scruffy kids in the back seat, waiting to gas up at Harry’s. Weather-beaten women in print dresses and bare feet, passing one another going to the bathroom where there was a mirror, and a chance to comb their hair. Then as quickly as they appeared, “Poof”, they’re gone. It’s no wonder the Hippies departing Haight-Ashbury, were attracted to this place.

There was a time when psychedelic-painted school buses, were a regular sight, coming through Santa Fe, headed north to the communes. One ran sideways of the Santa Fe police and the travellers jailed. Instantly cardboard signs popped up across town: “Free the Blue Bus ! !”. Long-time magistrate Quate Chavez, acknowledging he didn’t know what this was all about, sent them on their way. Totally aside, and not long after, the War Protest was coming, and Judge Chavez would have a lot on his hands. I was commandeered, with some complaining, to participate in that (another story).

So many memories ! ! Thanks, Will. JAT