Mad Men’s First Director of Recruitment, Bob Gale

BOB GALE

Bob Gale was six foot two, blue eyed, and owned a big personality. He was an academic coming to the Peace Corps from being the vice president for development at Carlton College in Northfield, Minnesota, and a Humphrey supporter.

Gale had decided he wanted to go to Washington with the New Frontier and work for the Peace Corps and got in touch with Hubert Humphrey, who he knew, and a meeting was arranged with Bill Haddad (another early Mad Man) who was already working at the agency.

William F. Haddad was the Associate Director for the Office of Planning and Evaluation. (At the age of 14 in post-Pearl Harbor, he had enlisted in the Army Air Corps pilot training program and advanced to cadet squadron commander before his true age was discovered.)

Haddad (who went on to become a Congressman from New York State) had come to the Peace Corps from being editor in chief of the Maco Publishing Company in New York and had been involved in the production of the famous pictorial essay, The Family of Man. He liked Gale because Gale was, in his eyes, “versatile.”

Haddad convinced Shriver to create an office called “Special Projects” and he put Gale in charge. It was an office free to do absolutely anything, a combination ombudsman and gadfly, a close cousin of the Division of Evaluation both logistically and philosophically.

I’m not sure Haddad had any idea (really) of who–or what!–they had in Bob Gale. But here is one story.

Gale was famous at Carlton College (which, if you don’t know, is an excellent college in Minnesota,) for having raised over twelve million dollars for an endowment in increase faculty salaries, student aid, and to launch an era of new buildings on campus.

When Gale arrives in Washington no one knew him. He had no real connections to the Kennedys, but he was hired and Haddad suggests that they go out for dinner to celebrate. Haddad wanted to go to the Jockey Club in the Fairfax Hotel, now the Ritz Carlton. “You never know who you’ll see there: Marlon Brando, Onassis, Lee Radziwill,” Haddad tells the mid-west boy from Saint Cloud, Minnesota.

But when Haddad and Gale walked into the Jockey Club there was Minoru Yamasaki, the famous architect, who would design the World Trade Center. He had already designed five of the new buildings at Carlton College when he had first met Gale. He greets Bob as a long-lost brother, and Haddad and Gale join their party and the Jockey Club’s famous maître d’, Jacques Vivien, never presents anyone a bill, and even joins the crowd when champagne is served in the early hours of the morning.

Welcome to Washington, D.C. and the Peace Corps, Bob!

Following Sarge’s approval for the new recruitment campaign, Gale went up to his rabbit warren of rooms and started to call everyone he knew at the University of Wisconsin. “They were all old pals of mine, and they were going ape over the phone about my plans for the Peace Corps at the university.

But it wasn’t an easy job. In 1963, the campus covered nine hundred acres on the shores of Lake Mendota. There were over 17,000 undergraduates, another 7,000 grad students.

Gale realized early on that he (and the Peace Corps) had to see the recruitment trip as a presidential campaign. There were two of them assigned by Sarge for the first campaign–Doug Kiker and Bob Gale–neither of them knew each other at HQ. Both were new to the Peace Corps. They couldn’t do it all Gale realized so he decided on a second team to arrive in Wisconsin a week after them. They would be the strategy for all future ‘blitz’ campaigns.

The “Wisconsin Plan” immediately became a two-week recruitment trip.

By midweek in this ‘advance’ week, Gale got hold of a highly guarded mailing list of all graduate students at Wisconsin, numbering nearly 7,000, which included medical and law students. It was a rich list of skilled people, just what the Peace Corps wanted. Gale called D.C. and asked them to send out a special mailing to these students by Friday so that they would get a letter on Monday, just as the follow-up team rolled into town.

Washington said no. It couldn’t be done. A dozen reasons why it couldn’t be done by D.C. were given. (All of this in the days before the Internet, remember!)

Gale told Doug Kiker, Chief of the Division of Public Information, ‘We’ve got to do it ourselves.”

“How?”

Gale told Kiker. “Write a press release saying that Peace Corps service is like another year or two of graduate school, and it is all free. List all the ‘Peace Corps stars’ who will be on campus next week.”

The letter was written, then 8 volunteer students gathered in the Student Union, (arranged by one of Gale’s pals at the University) who worked for twenty straight hours, stuffing envelopes and stamping them with a “Peace Corps, Washington, D.C. stamp that Gale had ‘borrowed’ from HQ.

“Is this legal,” Kiker asked Gale.

“Sure, why not?” Gale had no idea whether it was legal or not. (It wasn’t, as he would find out.)

Following that wild week on campus making arrangements with professors, the media, and the administration, Gale and Kiker drove to the airport in Madison on Sunday evening and met the follow-up team for Stage II of the Wisconsin Plan. They took the arrivals to their motel for a briefing, handing them their speaking and interview schedules for the week, gave them a map of the campus and a list of names they must memorize that very night. Then they flew back to D.C.

It was a simple political campaign. The Advance Team, then the follow-up team. For this first ‘blitz’ campaign the follow-up team was

- John D. Rockefeller IV, the future Senator;

- Padraic Kennedy, the future head of DVS for Peace Corps;

- Ted Sorensen’s first wife, Camilla. (Camilla married next Louis Hanson, and aide to the governor of Wisconsin, who went onto become a Regent of the University of Wisconsin.)

- Ellen Kennedy, Padraic’s wife, who had been a grad school in French at Madison three years earlier.

According to Coates Redmon in her book, Come As You Are, “The Wisconsin French majors were bowled over by the sight and the sound of a young, curly headed blond woman by the name of Mrs. Kennedy describing Peace Corps programs in French-speaking Africa–in fluent French.”

“The aim,” as Gale is quoted in Gerard T. Rice’s book, The Bold Experiment, “was to raise all kinds of hell without being idiotic.”

Literature was handed out in bulk, classes were interrupted for Peace Corps seminars, a colorful information booth was set up in the middle of campus, and every senior student was openly solicited as a potential recruit. The three recruiters were written up in the campus newspaper, the Daily Cardinal; they were on WIBA Radio, interviewed nightly while in Madison by WIBA famous disc jockey, Papa Hambone, the pseudonym of George Vukelich, who taught creative writing at the university.

Gale’s blitz campaign was forceful and aggressive. It was immediately effective. After one week, 426 Wisconsin students had applied for the Peace Corps, approximately 10 percent of the senior class.

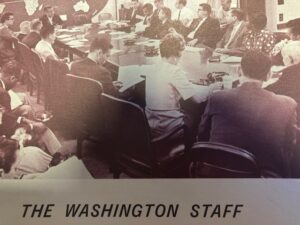

Postscript: One small detail. Since a few of the envelopes sent to the Wisconsin graduate students were misaddressed, they landed back at Peace Corps HQ. Howard Greenberg, the Associate Director for the Office of Management, saw then and realized what Gale had done. When Gale returned to D.C. Greenberg told Gale that he could have gotten five years in prison for every illegally franked envelope. Given seven thousand envelopes, that came to thirty-five thousand years in prison. Greenberg decided to let Gale get away free and was ready for the next senior staff meeting with Shriver and the Mad Men & Mad Women of Peace Corps/Washington. That was way the Peace Corps got things done before the ‘lawyers’ took over the agency.

On Campus

On Campus

Thanks for posting this story. What is really impressive is that the campus recruiting system that Bob Gale worked out in Wisconsin got duplicated all over the country. I was sent to a half-dozen schools, and we followed the exact plan — an advance team would go out ahead of time to scope out the campus, make contacts and set up appointments. Then the recruiters would come in to collect applications. Of course, as a 23-year old junior PC/W staffer, I got sent to second tier campuses — schools ike Montclair Teachers Colloege or Fairleigh Dickinson University, while the senior staff were assigned to more prestegeous universities like Cal Berkeley, UCLA and Harvard. I don’t know whether it was a mistaken assignment or just that Gale’s office had low expectations for southern schools, but, in 1964, I got sent to Georgia Tech and Emory University in Atlanta, two bigger schools that usually went to a more senior team. It was my first time in the south, and a lot was happening. Soon-to-be governor Lester Maddox was making headlines by handing out axe handles at his restaurant in open defiance of federal desegregation law, and SNCC, the radical Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was holding street demonstrations. Atlanta seemed to be at the center of the civil rights movement, and I loved being in the thick of it. We did well and got a good response from students at both schools. I also learned not to underestimate hese southern kids. They talked funny and often rather slowly, but they had quick minds and lots of interest in the Peace Corps.