“Looking for Albert Schweitzer in Lambarene, Gabon” by Eric Madeen (Gabon)

On Mission

By Eric Madeen (Gabon 1981-83)

Eric Madeen

What follows is a reconstruction of memories, which can be likened to partially developed film … at times hazy, at others gaining clarity like images in a developing tray … of one’s mind.

My mind. It was first being readied for what lay ahead by intensive French instruction for six weeks, followed by six more during work on rural school construction in Peace Corps/Gabon. With two years of Spanish at university as basecamp, French came easily; classes were named not by level, but by towns in Gabon. It didn’t take me long, however, to learn that mine, Ndende, was at a lower proficiency level.

Recent graduates from Ivy League schools to esteemed public ones, we numbered approximately 60 trainees in the programs of TEFL, Fisheries, Agriculture and Construction. We were lodged in a student dormitory whose Turkish shitters went down one by one since maintenance staff were seemingly also off for vacation. To avoid the lengthening lines and decreasing squatty potties, some of us men folk — hush, hush — were reduced to evacuating bladders in showers which by and by reeked of urine. TMI, I know.

After training and being sworn in as volunteers, my partner and I, along with village men, built a primary school complex in the equatorial village of Djidji (jee-jee).

Circling back to the former stage — or training, it was held at a lycee in Lambaréné during the dry season when the school was off.

During that stretch of French training in Lambaréné I made several trips over to the nearby Schweitzer Hospital to gather information about its founder, operations and august history for an article to be published in my hometown newspaper in Elgin, a Chicago suburb. As a university-trained journalist with several publications, I diligently pecked it out on my manual machine à écrire. After pouring much time and effort into its transcription I gave it, with some ceremony, to an American, Andy, who dropped out of our ensuing hands-on training in school construction in Franceville. Since he was heading home through Libreville I asked him to post it for me there.

As the ambitious article was prodigiously long and required much folding, it had a coiled-spring feel inside its flimsy envelope. How it sprang free enroute, alas, and left its airmail-striped wrapping in tatters will forever be a mystery. In short, it didn’t make it home and I’ve since regretted not posting it properly myself (carbons and reproducibilities not an option there and then). So we’re left with a soupçon of memories … and some pithy quotes.

The high school in Lambaréné was atop a hill. After French classes on Saturdays, which terminated early a la French system, I made a habit of gathering up my backpack of notebooks, camera and such to head to the Schweitzer Hospital. Descending the winding trail through rainforest and sepia, I marveled at storied foliage with boas of vines hanging low then U-turning up toward the canopy. Near a village I noticed how trees fell away to reveal manioc fields, the squawk of a rooster and chop of wood. Two boys saw me and I broke the ice by greeting them. They approached me timidly. Then one, emboldened now, made a point of holding up a single gloved hand and gesturing with it while saying something about an American singer, “un noir Americane … très famous.” Later it occurred to me that he was imitating Michael Jackson, who went viral then and wore his signature single glove … in concert, in music videos, in photos that hop-scotched the globe to this most remote of places on the west coast of Central Africa.

At the bottom of the hill was a pink, laterite road where I followed instructions by turning left. Two rows of mud huts lined the road. Under their eaves were barrels rolled there to catch rain for drinking water and cooking. Crevices in the road, carved out by erosion, widened in their fingering down the road.

With a friendly bonjour I passed a woman weighed down by a basket of firewood and tubers, then her man, ahead, clutching nothing more than a machete at his side. Roused, goats found their legs and decamped from my way.

I heard raised female voices and turned to note two teenaged girls waving to me as they appeared from a doorway. When I waved back they approached. In my miniscule French I answered their questions. They were clothed in wrap skirts and t-shirts and their faces were all smiles and giggles as they touched my arm, my chest, then up to my blond hair, fluffying it, saying it was soft like a baby’s hair. I made out that they were likening its blondness to an old man’s hair, making a joke of it, my mind catching comme un vieux homme. They lit up when they learned I was American, the first one they had met. They went on, … beau, très beau. (Aw shucks; while I may have cut a bello figuro then at 23, in this house of mirrors of time, now at 63 there’s no denying the bludgeons of … years). With nods they got my explanation that I was a stagiaire, a trainee, studying French up the hill at the lycée. Running short of the lingua franca I bade them farewell but later found it curious how they were there to greet me on a slew of Saturdays — more later.

I followed the road around a bend and came to the river and eventually, the boat landing. I wakened a pirogue taxi boatman lying on a mat under a mango tree, boat cushion as pillow. Hiring him with CFA — Bongo bills softened like cloth, he took me off island and across the Ogooue River to the hospital, which was a cluster of tin-roofed structures wedged into a hillside below the smoke of low hanging clouds.

Even though it was dry season, eddies and whirlpools swirled in the muddy water; the craft knifed through them under the power of a Johnson motor. After the pirogue nosed onto a sandy embankment I made my way gingerly off the craft then up the hill to the hospital — noting to the left and farther down the old hospital, and to the right and above the new.

The Village of Light which ironically was a leper colony

A Gabonese gardener was kind enough to lead me to the head nurse of the deceased doctor. Uniformed and British, she also acted as a guide to visitors and hitherto source for journalists. I introduced myself then explained my intentions. She crossed her arms and an origami creased her visage.

Annoyed, she exclaimed that yes, she was the head nurse but . . . “No, absolutely no more talking with journalists.” She repeated this and said she had been misquoted too many times amidst much misreporting. Steadfast, I challenged her, asking, “Because one nail is bent does that mean all nails are bent?” She registered this with headshake and left me standing there.

Later, after I hung around for a month of Saturdays and thus seemingly passed a smell check with upper echelons of hospital staff, she perhaps got word that I was not a bent nail — why she held forth to the American intern Dr. Hamilton, but obviously too loudly so as to include me in the range of hearing: a long list of hugely traumatic experiences she dealt with in her several years there, most disturbingly how, as a result of a poison war in a nearby village, the dead were carried in so fast and furious that there wasn’t time enough to build coffins; rather, they were sewn in banana leaves and buried in such.

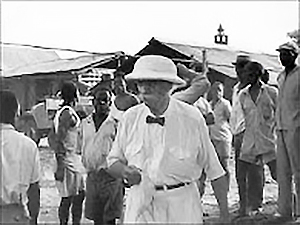

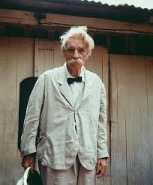

By poking around I found signage indicating the doctor’s elongated planked office and bedroom as the first building uphill on the right. Inside I took note of writings, assumedly philosophical, in notebooks and published hardbacks opened on shelving and in glass cases and figured the grand doctor did his correspondence at the modest wooden desk and chair. (In my mind’s eye the recollection of such a chair resonates with my writing chair, which I had a village master carpenter construct; it was of the precious hardwood moabi with nary a nail — all its hand-planing and Swiss watchery of joinery had him upping his price to an additional sack of hardening cement that was too chunky to mix and pour.) Notable was Schweitzer’s famous pith helmet, which reminded me of him under it in a B&W postcard of the man himself in my thick photo album, where he looks distinguished and interesting with wings of swept back gray hair and brush mustache, clad in a white uniform and foot, with black shoe, resting atop a pirogue riverside.

The same Gabonese gardener whom I had met on my first visit, took time out from his macheteing to lend an ear to my broken French asking to be led to another staffer, preferably of some stature: “Un docteur ou bien un infirmiere ou bien un patron si possible.” He led me to a planked house with a screened porch giving generously on the Ogooue-River below.

Knock, knock. He spouted it in the Gabonese version — “Ko, ko ko” — then announced me, my mission: “C’est un journalist …un Americain.” A rather squat and elderly woman with eyeglasses propped low on her nose ran a hand through her short cropped gray hair and greeted me. She said in perfect English that she was Dutch, and one of two surviving hires from Europe still laboring on after Schweitzer’s death in 1965. (He was born in Alsace, Germany as a son of a pastor in 1875.)

With good grace she seated me in a rattan chair. I opened a notebook and listened to the clear and precise English of Miss Maria J. Lagendijk explaining that she came, some four decades ago, to the hospital from Holland with graduate training as a nurse specialized in anesthesia, intensive care, midwifery and pharmacology.

I noted her listing numerous maladies that brought patients to the hospital, and just now checked for an update of such on the online site ESPEN, or Expanded Special Project for Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases: Malaria, Lymphatic filariasis, Loiasis, Onchocerasis, Soil-transmitted helminthiasis, Schistosomiasis (or snail fever in layman’s terms), Trachoma, etc., etc.

Maria added that there were numerous cases of injuries suffered from hippo attacks downriver, how in their territoriality hippos overturned pirogues then chomped on flailing appendages.

Fast forwarding in this slipstream of time to quote from an informative piece in the New York Times of March 1, 1988 “Le Schweitzer’ Still Inspires Deep Loyalty” by one James Brooke: “‘These roofs are the Nobel Peace Prize,’ Miss Lagendijk said, pointing to a dark red corrugated iron roof overhead; Dr. Schweitzer invested his Nobel Prize winnings in metal roofs for the hospital and for the adjacent leper colony, the Village of Light. Miss Lagendijk, [then] 80 years old, [was] the last European at the hospital to have worked with Dr. Schweitzer.”

The article went on: “‘He was a true Alsatian,’ said Miss Lagendijk. ‘He had the charm of a Frenchman and the solidity of a German.’ In 1938 she set sail from Europe for what was then called French Equatorial Africa.”

With each one being a year, take seven steps back to 1981 and my drawing her out. She recalled the interview with Dr. Schweitzer in the old country. She said he always asked his foreign staff these penetrating questions: 1. Do you have a sense of humor?; 2. How do you sleep at night?; 3. What are your hobbies?

These questions were largely germane to what was stressed in our Peace Corps cross culture classes, espousing not only cross-cultural sensitivity, but pointedly here stabilizers to turn to in times of stress and/or culture shock. Although my biggest shock was being lost for three days in the jungle as a result of hunting spot-nosed monkeys fleeing overhead in canopy and leading me off a maze of elephant trails and thus turning me all around, I didn’t suffer from such. After work when my nose wasn’t in a book I could be found scribbling, listening to music via my Walkman, or drinking Regab with village friends while relishing in le dialogue . . . .a la high-octane oral tradition, or orality. And when there was no beer (Where There Is No Doctor!) removing the thimble-stopper of leaf from a bottle of bitter palm wine or failing to find that imbibing that which went down like fire: miserable moonshine, or monumboka, which also meant “child of the village,” which I was so nicknamed in Djidji.

Despite that the year being way-back-when 1981, Maria lamented with prescience her concern of how the Sahara was coming south and how it wouldn’t be long before it encroached on forested Gabon …

Reporting in the Los Angeles Times on February 10, 1985, Louis B. Fleming wrote: “Some things have changed. A tangle of weeds covers the vegetable garden where Schweitzer struggled to duplicate, here almost on the Equator, the gardens of his birthplace in Alsace. ‘He grew tomatoes as big as this,’ Lagendyk recalled, forming a giant fruit with her hands.

“The new operating theater is air-conditioned. The controversial autocratic rule of that highly individualistic genius is now an institutionalized administration with support from foreign donors and the government of Gabon. His skepticism about the competence of Africans to be doctors has been replaced by an open door to Gabonese doctors, although few come. The sometimes-primitive medicine he practiced has been modernized, with special studies for Western medical students and a new research program coordinated with three European tropical medicine centers. And transport is by air or road, no longer on the river boats that first brought the Schweitzers here.

“But each patient’s family still cooks individually for the sick one and provides bedside care. Old wards have been converted to care for the mentally ill and homeless aged, services rare in West Africa. And on beyond the main hospital facilities, a treatment center for lepers continues Schweitzer’s pioneering work. “Progress comes slowly, however. Life expectancy for those born in Gabon today […] is only 49 years. Life for those in the bush has hardly been touched by Gabon’s petroleum wealth.”

Rewinding again to 1981 and my eagerness to take Maria Lagendyk up on introducing me to the American intern doing his residency at the hospital, Dr. Hamilton.

Perhaps keen to talk to a fellow American, he was forthcoming more than once; his recounting had me filling page after page. He told me how the hospital uses pairs of Harvard interns to doctor for six months a year and two Swiss interns the other six.

Le Grand Docteur among Gabonese he so loved

He said due to the high number of patients with varying maladies and understaffing he went from not only being the head internist to head almost everything: head surgeon, head ob-gyn, head pediatrician and head of a raft of other roles. In fact, he so impressed the English head nurse — who had snubbed me — with his pulling 18 to 20 hour days that she gifted him Schweitzer’s very own pith helmet. Dr. Hamilton spoke of his high regard for Dr. Schweitzer, saying that the missionary doctor was ingenious in using the extended family for patient care at the hospital, care that otherwise wouldn’t have been there since the hospital didn’t fall under the aegis of the Gabonese national health care system then.

While this ingenuity was an undeniable positive it begs the oft-heard criticism that Dr. Schweitzer failed to teach, or transfer to the Gabonese, from his Western medical bag during his time there from 1913 with his wife who served in multiple roles as well, foremost nurse and fund-raiser. It would imply racism to conjecture that the grand doctor thought the Gabonese were uneducable in the intricacies of Western medicine, and culturally arrogant to suggest that forest schools prevalent there and then in equatorial French Africa were insufficient preparation for learning such. However, my mind finds fathomless all the complexities that would go into, say, teaching how to measure and administer a simple dose of penicillin or insert a catheter for prep of a drip feed, if such were even available then.

After the obvious doctor/patient role went the polarities needed and thus embodied in Christianity that seemingly drove the doctor to do good works out of a Sunday school bag. There’s god/devil, savior/saved, saint/sinner, follower/infidel, ad nauseam to the point that perhaps there wasn’t precious time and energy enough for the dynamic of teacher/student. (As an educator myself I can attest to the tremendous time and energy suck that teaching demands — and its frustrations in keeping me from … humping the muse.)

So Schweitzer as a missionary doctor was there in Lambaréné, it is safe to assume, to save souls literally, figuratively and spiritually, but having to educate with blackboard clarity, since lives were at stake, would have been perhaps the proverbial straw … methinks. Albert Schweitzer, needless to say, was a man of much erudition, having studied theology and philosophy at the universities of Strasbourg, Paris, and Berlin; earning fame as an original and powerful theologian then philosopher, organist, musicologist and at 38 years of age, medical doctor. He thus clearly understood the ephemeral nature of time and in such profound understanding made the most of his.

Schweitzer’s modest gravestone on the banks of the Ogooué

With his wife Helene trained as a nurse who, however, suffered numerous illnesses which took her back and forth, the two decided to serve humanity in the missionary hospital they founded, and was then largely funded by him giving organ recitals in Europe. Perhaps as a matter of principle and/or pride, he was known to refuse donations and spent the remainder of his life in Gabon, winning a Nobel Peace Prize in 1952, then passing away in 1965 at the age of 90 in Lambaréné, where he’s buried near the riverbank next to his wife who died eight years before him at the age of 78.

With reason it can be assumed that going with the territory of the doctor’s amazing accomplishments went a high opinion of himself. Confirming this was one of our Gabonese French teachers who grew up in Lambaréné. Knowing of my mission, Jean Marc recalled an anecdote of crossing paths with the doctor when he, Jean Marc, was just a boy at play on hospital grounds. Seeing the doctor, he greeted him as such: “Bonjour, Docteur.”

Schweitzer nodded and asked for more honorific: “Et l’adjectiv, mon fils?”

“Bonjour, grand Docteur!”

And now developing in the witchery of memory was how after my last visit to the hospital, I returned through the same village — at about the same time it had been each Saturday afternoon. But only one of the girls was there . . ., as if in wait she ran from her hut, waving, exclaiming: “Monsieur Eric! Monsieur Eric!” Although her name escapes me she was the prettier of the two. While small talking and giggling and laughing we shook hands and a tell-tale finger scratched my palm. She rubbed my arm up to my bicep, which she squeezed. She reached up to stroke my cheek, the stubble there on my chin . . . in this touch up. I couldn’t help but begin to feel the stirrings of the demonic electric eel soon to swim up through the whole of me and touched her back, both of us confirming the truism that eros feeds on novelty. One thing … and … our touches became more intimate or rather sexual to the point that she hugged me, and being a young strapping lad like most young strapping lads I hugged her back. She eased me away to fumble with buttons and zipper. Her patterned wrap skirt was knotted at the hip and with a pull came off like a magician’s trick. In a flash — as flashers — we were beside the road buck naked and by the hand she led me down into a shallow gully skirting road and it was there in broad daylight that we made the double backed beast in youth and Lambaréné.

•

Eric Madeen (Gabon 1981-83) works out of Japan as an associate professor of English at Tokyo City University, adjunct professor at Keio University, and author of the forthcoming book of three novellas Tokyo-ing!, preceded by Asian Trail Mix: True Tales from Borneo to Japan. His Peace Corps inspired Water Drumming in the Soul: A Novel of Racy Love in the Heart of Africa is featured along with his other books and sundry at www.ericmadeen.com.

In a dream is how I read this autobiographical essay –so poetic– and it is as sweet and pink and white as young turnips. Swell and true as experienced. OK I say and even if it leaves you wondering of what has happened there up to today, this is enough now.

Thanks so very much, Edward!!! I just saw your comment and it made my day hugely. Hopefully you can click through to my website for a nosing around: http://www.ericmadeen.com.

You make my fingers (now old & 85) ache to write racing on the rails sailing as you do. You write with verve and vigor. All I can say further is to quote the San Francisco critic, poet, philosopher, novelist Lawrence Fixel (RIP) “keep on trucking”. Edward Mycue

The reasons for my reply, Edward, are bifurcated: 1. I would like to thank you again through my heart steering the glide of my ten digits and your turning me onto one Lawrence Fixel and on the note of The Beats I’m now ensconced in William S. Burroughs astounding “Junkie”; 2. Hope such a reply will keep my journalistic memoir from cascading down into the abyss of Peace Corps Worldwide. http://www.ericmadeen.com

I continue to enjoy your writing Etic San. Well done and very picturesque!

Thanks so very much, Uncle Stan!!! I’m so happy you enjoyed it!!! Your loving neph, Eric at http://www.ericmadeen.com.

After serving in PC in Senegal 1993-96 at 55 years old, I went at the end of my service to the Hopital Albert Schweitzer in Haiti where I was administrator for five years. Along with Board members I traveled to Gabon in 2001 to visit le grand docteur’s hospital in Lambarene. An unforgettable event.

As a PCV in Lambarene, Eric, you obviously didn’t observe the reverence for le grand docteur that so many disciples do. I find that refreshing. I’ll be sharing your story with friends and alumnae of HAS in Haiti. We will all get a kick out of it, for sure.

BTW I have some books authored by Schweitzer’s followers and by Dr. Larimer Mellon and his wife, Gwen, founders of the Haiti hospital. Also a biography of Helene Schweitzer by Patti Marxsen.

Thanks for the memories!! Reverence pour la Vie!

Leita Kaldi Davis

(Senegal 1993-96)

President, RPCV Gulf Coast Florida

Recipient Lillian Carter Award 2017

That you so much, Leita, for the read and sharing your impressive — to say the least! — service, which took you so far and wide. By the way, I initially sent the piece to the Albert Schweitzer Foundation U.K. While the founder was all for it the editorial director’s wanting to steer the journal to Le Grand Docteur’s writings resulted in a rejection there. Perhaps serendipitous, given the warm comments such as yours and multiple hits I’m getting here … chez nous. Warmly, Eric http://www.ericmadeen.com

I am proud of you

Thanks, Julie! Much appreciated!!!