In the New York Times: Norman Rush's Brilliantly Broken Promise

One of the few things that Sam Brown, who in 1977 was appointed head of Action under Jimmy Carter, did was to hire Elsa and Norm to be one of the first ‘couple’ directors of the agency. The story is that Brown met Elsa and Norm at a party, which is true, but the Rushes, like Sam Brown, had been heavily involved in anti-war politics for many years. Brown was looking for a successful ‘married couple’ to do the job. The Rushes were certainly that successful married couple.

PCVs who served under Elsa and Norm have only the highest praise for them as people and as co-directors. (The agency would be wise to think again of having ‘co-directors’ running countries.)

Their time in Botswana gave Rush, as he says in this interview, a direction for his fiction: “I knew that what I wanted to write about I would find in Africa,” he says. “I knew that the themes that were dominating my thinking in writing would show themselves in the setting. It was a part of Africa with social experimentation going on that had achieved a certain degree of independence, and Americans and Americanity would be manifest in a different way.” He would begin to write his stories of Africa after leaving Botswana beginning with his collection of stories, Whites and next, Mating.

I have met Norm and Elsa and know them very slightly. The first time I met Elsa, as a book signing for Norm in New York City, she could not have been more gracious, approachable, as well as, beautiful. When she read (years later) on-line that I was briefly taking time off from this site she knew something was up and telephoned me at the hospital to make sure I was okay, and that the operation had been successfully. This was only after having met me once. It is no wonder PCVs in Botswana remember her with such affection.

Norm credits Elsa for his success as a writer. She is his first reader and his more astute editor. Read this long, wonderful, and endearing article about fine people who give all of in the Peace Corps Community a better name and something to be proud of.]

August 29, 2013

Norman Rush’s Brilliantly Broken Promise

By WYATT MASON

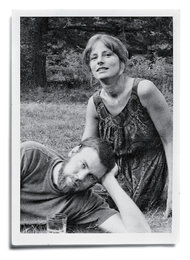

One afternoon at the end of the summer of 2011, on the shady porch of a little red farmhouse near High Tor, in Rockland County, N.Y., the novelist Norman Rush, vigorous at 77, revealed himself as a man of great frankness. “I completely betrayed her,” Rush told me, astonishment in his voice over what he’d done to the woman sitting across from him, Elsa Rush, 76, his wife of 56 years.

The three of us were at a table messy with the remains of lunch, a pair of flies making drunken arcs above our empty plates. Broad-chested and white-bearded, with an expression alternately jolly and severe, Rush looked to his wife. Elsa, as emotionally direct as Rush is conversationally frank, is a tall, unfussily elegant woman whom Rush often calls, both in and out of her presence and never emptily, “my beautiful wife.” Looking off the porch of the house she and Rush have shared for half a century, Elsa was facing the lawned woodland adjoining us, sunken slightly in its center like a saddle.

“The way I put it to Norman,” Elsa said, turning to her husband, “was, ‘Whatever you want to write, that’s fine.’ If you had said, ‘I’m going to spend 10 years, and I’m going to write a book about this – ,’ can you imagine me saying: ‘No! You’re not going to do that!’ Can you imagine it?”

In retrospect, Rush should have known that what he was doing could lead only to betrayal, given a set of statistics well known to them both. His first book, “Whites” (1986), a collection of stories that was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, wasn’t published until he was 52; his first novel, the 477-page, National Book Award-winning “Mating” (1991), took eight years to write; his second novel, the 712-page “Mortals” (2003), took 10 years. And yet, upon the appearance of “Mortals,” Rush told Elsa – promised her – that his next novel would be a mere 180 pages and take two years to complete. But there we were on their porch in 2011, eight years later, and the “next novel” – “Subtle Bodies,” which is at last being published this month – was, as of that date, quite a bit longer than 180 pages and still not finished.

“A hundred and eighty pages,” Elsa said. “Taking two years. . . . You’ve never done anything like that before, so why did you persuade me?”

Throughout his career, Rush has been candid about Elsa’s involvement in his writing. Not a literary spouse who stealthily delivers cups of tea to the genius in the attic, Elsa is what Rush calls “a partner in the process,” which he describes as “a battle waged in common.” Testimony on the depth of their artistic partnership may be found on the dedication pages of his books – dedications that are minor masterpieces of a characteristically trivial genre.

“Everything I write is for Elsa,” begins the dedication to “Mating,” “but especially this book, since in it her heart, sensibility and intellect are so signally – if perforce esoterically – celebrated and exploited. My debt to her, in art and in life, grows however much I put against it.”

But as the years passed after the two-year deadline expired, Rush’s debt to Elsa (“the last 10 years of extraordinary forbearance,” as he writes in the dedication to “Mortals”) compounded at an accelerating rate. The battle waged in common became a struggle Rush felt ashamed to share.

“Guilt will stop you in your tracks,” Rush said, of the years that followed his promise. “And I began feeling guilty about this book when it diverged so radically from its original, simpler formulation. Because it was taking time out of our life when there are lots of fun things we could do if I just stopped writing.”

For a fiction writer who has counted among his admirers the Nobel laureates J. M. Coetzee and Nadine Gordimer, not to say a diverse generation of younger writers that includes Benjamin Kunkel and Tom Bissell, Rush’s notion of stopping writing was neither desirable nor reasonable – least of all to Elsa, who says, with unfeignable ardor, “I love everything Norman writes!” As such, she found herself clearing their schedule – of cruises booked; hotels reserved; invitations from friends – when Rush needed to keep to his desk. Still, Elsa found it difficult not to grow distressed.

“A very good part of Norman,” she said, as afternoon became dusk, “is the never-giving-up part. He’s good at internal philosophy, at rising above defeat and helping other people do that, helping me do that. So I think it was partly magical thinking, his declaration, that isn’t entirely magical. I think it’s a question of willing himself into doing something he wants to do by making a statement that he’s going to do it. The question is: How aware is he of that mechanism?”

An awareness of the mechanism – of how our minds work, of the transits between self-certainty and self-doubt and the endless inner arbitrations litigating each – is a central Rushian preoccupation. Of course, most works of fiction engage, at some level, with the imaginative leap that allows us to cross into the cloistered consciousness of another. But Rush’s own demonstration of that process – of voice as a measure of the mind – has been unusual.

“Until you got into it,” Rush’s editor of 30 years, Ann Close, told me of the narrator of Rush’s first novel, “Mating,” “you couldn’t have imagined that voice. It’s extremely intimate. Wise and ironic. There’s a kind of joy in it.” That voice belongs to an unnamed woman who tells us her “personal automatic pastime [is] questioning my own motives.” An anthropologist in her 30s whose Ph.D. thesis has stalled, she undertakes a period of sentimental education in Botswana that, though unlikely to jump-start her dissertation, might land her a mate. Her ultimate target is a radical in his 40s, Nelson Denoon, an expat development director, part George Clooney, part Simone de Beauvoir, who has set up a self-sustaining matriarchal utopia in the Kalahari Desert for destitute African women. The narrator pursues him with candor and ardor, plunging into the desert, as Close put it, “with her whole heart.”

That passion is present when the narrator meets Denoon, a moment she preambles with: “I hate drama. I hate dramatisers. But it was distinctly like a building falling on me when I met him.” Wholehearted, she also thinks in complete paragraphs:

Intellectual love is a particular hazard for educated women, I think. Certain conditions have to obtain. You meet someone – I would specify of the opposite sex, but this is obviously me being hyperparochial – who strikes you as having persuasive and well-founded answers to questions on the order of Where is the world going? These are distinctly not meaning-of-life questions. One thing Denoon did convince me of is that all answers so far to the question What is the meaning of life? dissolve into ascertaining what some hypostatized superior entity wants you to be doing, id est ascertaining how, and to whom or what, you should be in an obedience relationship. The proof of this is that no one would ever say, if he or she had been convinced that life was totally random and accidental in origin and evolution, that he or she had found the meaning of life. So, fundamentally, intellectual love is for a secular mind, because if you discover that someone, however smart, is – he has neglected to mention – a Thomist or in Baha’i, you think of him as a slave to something uninteresting.

For nearly 500 pages, the narrator shows herself to be a lusty thinker, as analytically avid as she is sexually frank, a style of mind that mixes spoken effects (“I think”) with notes from a higher register (“id est“). “I know it sounds absurd,” Rush said in 1991, “but I wanted to create the most fully realized female character in the English language.” For many, he pulled it off. In a poll by The New York Times Book Review in 2006, a jury of more than a hundred writers, critics and editors said “Mating” was among the best novels of the past quarter-century. Even so, a few outliers didn’t buy “Mating.” “Presumably attempts at satire are afoot – satire of male-female tensions, of Denoon’s utopianism, of the narrator’s academic language,” wrote Jonathan Yardley in The Washington Post in 1991, “but it is just about impossible to distinguish satire from solemnity in a novel that possesses far more of the latter than the former.” Among the male writers I spoke to who were not taken with the book, the reason given was that they didn’t believe this could be a woman’s voice. The novelist Mona Simpson objected vigorously.

“Would these male literary writers,” Simpson said, “object to the ending of ‘Ulysses’? To the scene inside Anna Karenina’s head before she throws herself onto the train tracks? To ‘Madame Bovary’? Maybe these male writers can swallow the idea of Tolstoy and Flaubert and Joyce capturing the essence of a woman’s extreme emotional life but not necessarily her long rational disquisitions about politics, utopias and their discontents.”

If in “Mating” Rush took on the rationality of female thought, in his next novel, “Mortals,” he explored the irrationality of male thinking: in 700 pages from the perspective of Ray Finch, a C.I.A. operative in Botswana, “Mortals” reveals a man passionately interested in a wife who is losing interest in him.

“If you look at both ‘Mating’ and ‘Mortals,’ ” the critic and novelist James Wood told me, “it seems that the question of gender is somewhat less important than the question of what it is to see a consciousness in action. Both main characters in the two novels are slightly crazy – in the way that if you spent 50 hours inside the mind of anyone else, you’d be begging to be let out. I love the way Rush seems to incorporate intermittent hesitations of thought, so even when his characters are thinking ‘rationally,’ it’s a very irrational rationality. That’s the way in which we’re unrealistic even to ourselves. We don’t add up.”

Norman Rush was born in San Francisco in October 1933. His father, Roger, was a trade-union organizer from Oregon and was the California state secretary of the Socialist Party. Or was at the time of Norman’s conception. After a fling with a young woman named Leslie to which Rush owes his existence, Roger left town.

“The two mothers dragged him back,” Rush told me on their porch.

“Leslie’s mother found Roger’s mother,” Elsa said. “There was a shotgun wedding.”

Roger, with a young family to support, took a job very different from his previous work.

“He worked as a salesman for a printer,” Rush said.

“This is so sad.”

“A lifetime of . . . she never forgave him for the fact that she had to force him to marry her.”

“You can imagine, from her point of view,” Elsa said. “She thought they were in love, and he forgot about her. A life in which he was continually in a state of guilt and appeasement toward her. He could do nothing that would offend her. Or darken her view of him.”

“He was, essentially, a subject of my mother.”

Rush recalls a time during his childhood when his father was recuperating from a procedure in the hospital. “He had rather pathetically developed a habit of making jewelry at home. And he developed an affection for one of the nurses, and gave one of these things that were piling up to the nurse.”

“Leslie forced him to take it back,” Elsa said.

“To make succinct the degree of domination,” Norman said.

“And he worked very hard all day,” Elsa added. “And she would just sit around. A subject of hilarity among Norman’s siblings ” – Rush is the eldest of five – “is that she was reading ‘The Egyptian’ ” – a historical novel of the ’40s – “for months, and the children would see that she was two pages further on. Not until her husband came home would she get up. He would do everything with her: make the supper; do the laundry; do the shopping with her and earn the living, and he can’t even give away a damn smooth stone for personal gratification.”

“His life was reparations,” Norman said.

That it could have been very different was a fact Rush grew up less understanding than withstanding. His father had aspirations as a writer, wrote poetry throughout his childhood and, later, Socialist protest poems in the style of Whitman for a journal he published called The Rebel. But all that went away during Rush’s boyhood, his father becoming the antithesis of his former self: not merely a salesman but a trainer of salesmen. As Rush said when he accepted the National Book Award for “Mating”: “The trick on me was that he abandoned his original definition of himself before I had much chance to react against it, which left me with little choice but somehow to honor it.”

The youthful form that honoring took was a sort of graphomaniacal mirror image of his father’s former ambitions, actions Rush has called “filial-pietistic,” defined as “the carrying out of the perceived life-project of a dominant parent, the replication of it if the project has been successful or the completion of it if it has been thwarted.” Rush began to write “because my father didn’t or wouldn’t.” And all of Rush’s published work contains a political questing consistent with his father’s socialist leanings. At their heart, all his books find ways of asking if the choices we have made, as a civilization, are humanizing or harrowing.

At 11, Rush wrote a picaresque novel called “A Modern Buccaneer” that was published serially in a newspaper called The Town Crier – a newspaper that Rush printed by hand and sold door to door. There were dozens of comic books he wrote and illustrated as well as imitations of G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown stories; a novel in his teens that took the form of the journal of a Phoenician pirate; and another novel that he produced during nine months in prison for resisting the Korean War draft – this one in the style of Conrad, about pacifist adventurers in Central America trying to overthrow a dictator with the name Larco Tur.

That novel, as well as all that preceded it and much that would follow, was lost or destroyed by Rush before he got to Swarthmore, in 1953, shortly after getting out of prison. It was there that he met Elsa, in a room full of men he bested verbally. She returned to her dorm and declared to her friends that she’d found the man she would marry.

“Ever since I’ve known Norman, I knew Norman as a writer. Before I even read the first thing he ever wrote, I thought of him as a writer. And I thought the things he wrote were so interesting. Even on grocery lists, he wrote notes of things that were in his head. I saved scraps just because I felt that I had this secret that the way that his mind works is so interesting.”

Romantic though their beginnings might have been, the full picture was somewhat less gay. Neither knew quite what a relationship was supposed to be. Elsa’s family life was not without its own emotional upheavals. “My mother had many good qualities,” she said, “but she was crazy.” And Rush calls the specter of his parents’ strained marriage “an evil eidolon.”

“The place that I was attempting to emerge from,” Rush told me, as we sat with Elsa, “was not a good place when it came to the relationship with a woman.” His parents’ marriage hadn’t prepared him for the notion of mutual respect. “It was a miserable thing, given my background, especially with a superior woman who wants to be and is, in fact, an equal in the creative process – ”

“I don’t want to be an equal in the creative process,” Elsa said.

“You’ve always been my first reader. It was agony in the early days.”

“I just want to say what I think. I know I’m not an equal. I’d be writing if I were an equal.”

“Forget about the term ‘equal.’ You’re a partner.”

“That would be so outrageous,” Elsa said.

“Anyway. My initial reaction was to become a son of a bitch chauvinist – ”

“He would insult me.”

” – who, at Swarthmore, would knock his glass on the table for you to go get him more milk,” Rush said.

“I was like a slave.”

“And tell you to go back into the kitchen and say, ‘Norman Rush sends his compliments to the chef.’ ”

“You were 19, and I was 18. It was just childish.”

After college, they moved to Mount Pleasant, N.Y., where they lived after their first child was born, in a cheap house too large to heat fully in winter and therefore without running water in the coldest months.

“Norman was working for a builder-contractor. Putting on shingles and digging ditches. I was hand-washing diapers on top of our wood stoves. I would go out and cut down trees by hand. Chop them up. Burn them. Go to the creek. Break the ice. Take the buckets of water, heat them on the wood stove.”

I suggested that this was perhaps not the easiest of situations for a young mother.

“When you’re young, you’re just happy. Nothing hurts. I felt happy. He was working like a dog, but I had the fun of the baby.”

Rush was writing constantly and “began to publish highly sporadically in literary quarterlies,” mostly poetry, at the time, all of which he has since burned.

“I can quote you one of them: ‘Febrile immaculate Paul Valéry/Nine years before’ – um – ‘hostilities commenced’ – I’m now paraphrasing – ‘On the other side of the Pyrenees/Nos vrais ennemis sont silencieux/Thereby engaging his sect of talents.’ . . . And I’ve lost the last line.”

“Oh, well,” Elsa said. They laughed.

By the early ’60s, the Rushes had moved to the farmhouse in New City. Elsa worked as a weaver and designer; she installed looms in the house and later directed a preschool program nearby. Rush went from physical labor to antiquarian bookseller and for a time taught at a community college. All the while, he was writing. The occasional poem was published, but his prose of the era, “a sequence of experimental, abstract, excruciatingly self-referential novellas,” languished.

“Even those early, insanely arcane specialized writings,” Elsa said, “I thought they were really interesting, and if he wanted to do that, he should have a right to do that, but I don’t think you have a right to do that and then say,” Elsa adopted a poor-me voice, ” ‘Nobody really appreciates this!’ ” Norman laughed.

“He got so many rejection slips. But whenever anyone asked him what he was, he would say, ‘I’m a writer.’ We were at a social occasion once, and someone said to Norman, ‘What do you do?’ And it was the first time I ever heard him say, ‘I’m a book dealer.’ And I thought, He’s given up. You can’t say you’re a writer if you’re not significantly published forever.”

I asked Rush if he remembered the moment.

“Yep. I didn’t say it again.”

“It might be,” Elsa offered, “because I was crying so much. It really upset me.”

At a party in the early 1970s, the Rushes met the head of the agency that oversaw the Peace Corps, who was looking for married couples to serve as directors of various outreaches in Africa. The main requirement was a stable marriage of at least 20 years. “We both sensed about it that it would change everything,” Rush told me. “At the time Elsa was a weaver and colorist, and her knees were giving out from that loom – it was a trajectory that had become limiting. And I knew that what I wanted to write about I would find in Africa. I knew that the themes that were dominating my thinking in writing would show themselves in the setting. It was a part of Africa with social experimentation going on that had achieved a certain degree of independence, and Americans and Americanity would be manifest in a different way.”

After a series of interviews, the Peace Corps offered to hire Norman and Elsa as directors in Botswana, where they would have a 20-person staff and as many as 180 volunteers to coordinate. And then before they agreed to go, The New Yorker accepted a story by Rush – the first that would appear in its pages. Rush describes the moment as liberating. It was easier to leave the country knowing that he had at last been significantly published. Once in Africa, however, writing was put on hold.

“We were working seven days, nonstop,” Elsa told me. “We took two one-week vacations in five years.” After five years, though Rush had written nothing, he had come back with three cartons of notes. As they settled back down into life in New City, Rush set to writing new stories, now set in Africa. The New Yorker began to run them; Knopf agreed to publish them, and “Whites” appeared and became a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. There was even scuttlebutt, after the prize went to another writer, that the jury had picked Rush but the board decided to disregard the jury’s choice.

“I read about it in Newsweek,” Ann Close told me. “Apparently, the jury were all very mad. No one knows what happened.”

Thanks to the Internet, we now know why they were mad. After a little searching, I came upon the jury report from that year. For the 1987 fiction prize, the jury was tasked with choosing three books to recommend to the board, a duty the jurors admitted, in an impassioned report, they could not execute: “Although we were urged not to weight our recommendations, we must respectfully report that we cannot refrain from so doing. It is our unanimous recommendation that Norman Rush’s collection of remarkable stories, ‘Whites,’ is alone worthy of this year’s Pulitzer Prize for fiction.”

I showed the report to Rush and Elsa. They had not seen it.

“That’s wonderful,” Rush said, without the least irony. “What a piece of detective work! Do you know what a difference it would have made to my writing life if I had gotten a Pulitzer that year? Oh, I think it would have changed everything. My future steps.”

“It would have changed who he was.”

“I was still in the book business in those days. That’s what we were living on. It would have made a material difference.”

“But I think the most important thing would have been it would have changed him. He would have had more opportunities to do reviews and other things in the writing world.”

Absent those distractions, Rush was able to remain in his small attic office, piled with papers and books, to write two great novels about men and women and to discuss them – and the novel form – with Elsa.

“There is a long-term debate,” Rush told me, looking to Elsa.

“I’ve always thought that people enjoy reading things that move right along and things happen,” Elsa said. “People sitting around thinking can be too much.”

“I think she’s right. Obsessions with sweet, silent thought can go on too long.”

“We’re also talking about a tendency to exhaust a particular subject.”

In “Mortals,” for example, Rush included a long poem by the forgotten satirist and antimonarchist Robert Brough, which the operative Ray Finch is given to read aloud.

“We’ve never had anything I’d call a fight on this subject,” Elsa said, “because it’s clear who the boss is of what he’s going to write on a page. The closest thing we’ve had to a fight is: You’re insane. If you include the whole poem” – 154 lines across 22 stanzas – “you’re self-destructive and insane.”

“An act of homage to a fighter.”

“Talk about self-indulgent!”

“Didn’t I agree to take most of that poem out? It’s now just snippets” – 14 lines across 2 stanzas – “of this magnificent thing.”

More than a voice of reason, Elsa has also saved books from the fire. “Subtle Bodies,” for one.

“It was late at night,” Elsa told me, “and he said, ‘I can’t finish the book.’ And I knew that he was just very tired. And I didn’t know very much about the book. And I got a yellow pad, and I said: ‘Let’s talk about it. Just tell me some things about it. Tell me when we get to the point where you’re confused. Ten pages of handwritten notes. These don’t seem to be insuperable problems. When I ask, you have an answer. You just seem to be tired.’ I asked: ‘Do you think you could resolve it by going in this way? Look at it again in the morning.’ I don’t even know if he followed those notes.”

“I did.”

“Subtle Bodies” isn’t 180 pages, but it is Rush’s shortest novel by far. Rush says that much of the added time came in his trying to cut it down. The underlying plot is deceptively simple: a group of male college friends separated by a quarter-century of adult activity comes back together to bury Douglas, the group’s de facto leader. Rush has said in interviews that “Subtle Bodies” is about friendship; “Mating,” courtship; “Mortals,” marriage. It’s a clever formulation, but I would say that “Subtle Bodies” – like all Rush’s books – is about distinct minds in conversation, which seems to be Rush’s idea of marriage. “Subtle Bodies” is written from both a female and a male perspective, narrated in the third person with alternating chapters given to the voices of a husband and wife, 48-year-old Ned and 37-year-old Nina. As soon as Ned gets the news of Douglas’s death, Ned travels from California to the Catskills for the burial. Ned and Nina have been trying for some time to get pregnant, and Nina is furious that Ned has abandoned her at the time in the month when she is most fertile. It is a book about conception in all senses, particularly the human need to make and use language, and the ways that words like “love” and “friendship” and “loss” and “marriage” are conceptions themselves, often misleadingly defined and insufficiently comprehended.

Two years after my initial visit to the Rushes, I returned to their red farmhouse in the weeks before “Subtle Bodies” was to be published. Rush will be 80 in October, but he still has the solid, avid mind on display in the latest novel. When I arrived, Elsa was just beginning to set some hors d’oeuvres on the table.

“Come on the porch. We’ll get started while Elsa does frau . . . frau work.”

“All I’m going to do is put things on this and have you take what you want,” Elsa said.

“I want to get back to something we were talking about before,” Rush said, “about the long arc that this book has traveled. How can I say this without seeming grandiose? The sense of things in the world has come to feel increasingly apocalyptic. In a personal sense, the parts of the world that I follow and am interested in, things seem to be going quite . . . badly. Increasingly so. That raises questions of what writing is for. And as I was writing this book, this feeling was deepening in me, and there’s an occult connection between what you do and what its potential significance is in a time of crisis. What does it do?”

“And how might it help,” Elsa said.

“I probably have to reduce it to a cartoon to make it even clear to myself. You’re an artist. You’re not a nuclear engineer, you’re not a statesman, you’re not the head of the World Bank, you’re nothing, really, in terms of who pulls the strings of the world. You change nothing. None of your acts are designed to change things. You don’t make policy.”

Elsa looked at her husband. “What about Harriet Beecher Stowe?”

They laughed.

“So it’s the question of can it be more than doing nothing when you create something that witnesses a particular atmosphere. World historical cultural atmosphere. Can it be more than that? I think that acted as a drag on me.”

“Because,” Elsa said, “you wanted so much for it to be yes.”

“Of course. The answer is you do your witness and you see what comes out.”

“The answer is you probably don’t see. Maybe it’s like a little match, and you don’t know whether it’s gonna light a flame in someone a little less ineffectual.”

“A politician,” Norman said, “like a real person.”

“Rick Perry,” Elsa said.

“Anthony Weiner,” I said.

Banter of this sort went on, and on, throughout the day, and at a certain point, Elsa turned to Rush and said, “I think you should apologize to me for ‘frau work.’ ”

“That was said with complete – ”

“But it didn’t sound like a joke. It came from someplace. From another century.”

“Oh, no.”

“You’ve never used the phrase. You’ve never used ‘woman’s work.’ ”

“It was done with – ”

“I understand. Because I know you. But I was looking forward to putting this food out. That is: I like you. And then I wasn’t enjoying myself.”

“I am so sorry.” Rush sounded stricken, truly.

“I know you are. So it’s all over now.”

“Oh, no. I’m so sorry.”

“I knew if I mentioned it you would feel horrible.”

“Oh, my God. It was done with so much self-conscious irony.”

“I know that. But you didn’t show it. I’m not an idiot. I would have noticed if you’d said anything like that in 60 years.”

“Oh, my God. Kill me now. Don’t wait.”

Laughter, forgiveness.

Elsa went inside to get lunch.

Relationships, I said, as if it were just a word.

“Even in the most practiced ones, as you see.”

I told Rush that I was moved by the genuineness of his apology.

“It goes to show you that delicacies remain, even after years of practice.”

Rush was silent a moment.

“The rest,” Rush said, quickly, “has been the normal development and maturation of feeling. Discovering how much you owe to the other person in a basic way. I think I had a potential to be a much more erratic and crazy person in my ambitions, and she was perfect for me in that way. And she came from a tough emotional background, and she needed me – she needed to know that there was nobody else that I would have in the world either that I could imagine or had run into. So. So that continued. We’ve been so lucky that way.”

Wyatt Mason is a contributing writer for the magazine and senior fellow of the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College.

Editor: Sheila Glaser

What a beautiful collaboration! Do you think, John, that now that the current novel is completed, that the Rushes would agree to be interviewed by you about their time as Co-Country Directors with Peace Corps?