“Impressions of Cuba” by Patricia Taylor Edmisten (Peru)

•

Impressions of Cuba

A Thirty-Year Retrospective

by Patricia Taylor Edmisten (Peru 1962-64)

•

Why Cuba?

The year before my mother married my dad, she and her cousin Celia took a Greyhound bus from Milwaukee to Miami. After sight-seeing in Miami, they took an amphibian plane to Havana where they ran into some wealthy American men (playboys) who showed them the sights, including the newly opened Tropicana night club that still entertains visitors with scantily clad women dancing to fiery salsa. I don’t know why my mother, a first-generation daughter of a Bavarian-born pastry chef, chose Cuba. Her affinity toward Latin America developed after that trip even though she returned only once, after she had talked my dad into a family road trip from Milwaukee to Mexico City and Acapulco in 1956.

It was my mother who encouraged me to say yes to a 1962 telegram from Sargent Shriver inviting me to train for a Peace Corps assignment in Peru. Those two years had a direct or indirect effect on most of the important decisions I have made in my life, an impact most returned Volunteers will recognize. Here I’ll mention only those crossroads that took me to Cuba.

The Mariel Boat Lift

Between April 15 and October 31, 1980, approximately 125,000 Cubans reached Florida. Dire living and economic conditions prompted 10,000 refugees to seek asylum on the grounds of the Peruvian Embassy in Havana. President Castro gave the go-ahead for Cubans to depart for the United States from the port of Mariel. In the United States, meanwhile, Cuban-Americans orchestrated a flotilla of 300 boats that picked up the Marielitos. Little did they or President Carter know that among the refugees would be prison inmates and patients from mental hospitals that Castro released.

I was teaching at the University of West Florida (UWF) in Pensacola when on May 3, 1980, a call came out for speakers of Spanish to serve as translators at Eglin Air Force Base in the nearby Florida Panhandle. It had just opened as a processing and resettling center for the Cuban refugees.

My days at Eglin blur now, but there is an episode I’ll never forget: A medic asked me to translate for an unruly patient in the medical clinic. I stood beside the handsome young man with long curly black hair, trying to calm him as a doctor examined him. When the doctor turned away, the patient grabbed a scissors from the nearby tray and tried to stab the doctor. Military police subdued the patient and asked me to accompany him in an ambulance that whisked him away to the psychiatric unit of the base hospital. I remember kissing him on the cheek when I said goodbye to him in his cell, trying to reassure him that all would be well.

Overview of four visits: 1986, 1994, 2002, and 2016

1986

My interest in Cuba and its people grew after my time at Eglin.

Patricia on balcony across from Havana Cathedral, 1986

I first visited the island nation in 1986 with a small group of teacher educators sponsored by the Cuban Studies Association, now known as the Center for Cuban Studies. Located in New York City, this academic and research-oriented organization still arranges specialized tours. While in Cuba, we visited educational institutions in and around Havana, covering pre-school through university. Our group stayed at an elegant casa de protocol, or protocol house, in the Miramar section of Havana. It had been owned by a wealthy family but now belonged to the State.

One of the first goals of the revolution was to spread literacy among all Cuban people. Educators trained literacy brigades that were dispersed throughout the country. Cubans who could read and write had the obligation to teach those who couldn’t. As a result of that long endeavor, Cuba’s literacy rate shot up and competed with the world’s most developed countries, including the United States. It was, and still is, in the schools that children learn to be loyal to their government and its political philosophy, not only through texts and the modeling of their teachers, but also through recitation and song. The last line of one of the songs children sang for us had the refrain, “Soy Comunista, Soy Comunista, Soy Comunista, hasta morir.” (“I am a Communist until I die.”)

1994

In 1994 I returned to Cuba on my own, as Director of International Education and Programs at UWF. After months of letter writing and countless obstacles, I secured a visa through the Cuban Interest Section, located in the Swiss Embassy in Washington, D.C. While in Havana I succeeded in signing a Memorandum of Agreement with the University of Havana for my university that would permit student and faculty exchanges. We became one of only eight U.S. universities with such exchanges.

At the time, I had the pleasure of meeting vibrant women professors whose families were suffering the bitter shortages brought on by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the withdrawal of their aid. Known as the “Special Period,” Cubans lacked basic foods and household products. Many went hungry. Their health was undermined.

During that period I accompanied one of the professors to a neighborhood ration shop where a woefully Spartan mix of staples like cooking oil, rice, beans, and laundry soap sat on splintered shelves. Upon leaving, the shop monitor marked the date and documented the professor’s acquisitions on her ration card that every Cuban is still issued. In an effort to acquire more dollars for foreign exchange, the State also ran “Dollar Stores” where foreigners could buy whatever luxuries they wanted, as long as they had dollars.

A major cultural shift occurred in Cuba during my visit with the showing of the movie, Fresa y Chocolate (Strawberry and Chocolate). I was present at the film festival at which it premiered. Based on the novel by Senel Paz, the story examined the widespread homophobia in Cuba through characters shaped by Soviet-style authoritarianism. The movie celebrated the protagonist’s quest for freedom, not only in terms of his sexual orientation, but also in terms of political ideology. Audiences went wild, standing, clapping, shouting their approval. They seemed shocked that they had been allowed to see the movie.

A major cultural shift occurred in Cuba during my visit with the showing of the movie, Fresa y Chocolate (Strawberry and Chocolate). I was present at the film festival at which it premiered. Based on the novel by Senel Paz, the story examined the widespread homophobia in Cuba through characters shaped by Soviet-style authoritarianism. The movie celebrated the protagonist’s quest for freedom, not only in terms of his sexual orientation, but also in terms of political ideology. Audiences went wild, standing, clapping, shouting their approval. They seemed shocked that they had been allowed to see the movie.

As social restrictions in Cuba eased, some Cuban-Americans engaged in intimidation tactics that, if carried out today, would be labeled an act of terrorism. After returning home from the 1994 trip, I received a letter — a death threat — from a group called “Alpha 66.” Their motto appeared below their name: “Death before Slavery.” The unsigned letter declared that its members were at the “final confrontation, about to achieve . . . the definitive victory that will bring about longed-for liberty and democracy to suffering Cuba . . ..” It continued:

Conscious that we are the valorous and tenacious flag-bearers, we proclaim today that all those persons who visit Cuba, dialogue, or directly or indirectly support the ungovernment [sic] that oppresses our people, regardless of nationality, will be declared military objectives and will suffer the consequences, within or outside of Cuba. Our commandos achieve victory . . ..Those who dare ignore our call will tremble in fear before the violence. We will not make useless and unjustified distinctions.

Alpha 66 is a paramilitary group named for its original 66 members. It’s the oldest anti-Castro group in Florida. Apparently, its members saw no contradiction between their threats and the behavior they condemned in Cuba.

2002

In 2002 my husband and I visited Cuba with seven other members of the Cuban Health Network, then headquartered in Mobile, Alabama, a sister city to Havana. We traveled under the auspices of World Reach, licensed by the U.S. Department of Treasury. The organization already had a long history of humanitarian assistance in Cuba. In fact, they paid for the Network’s first shipment of medical supplies from North Carolina to Montreal— because of the U.S. embargo, where, it was picked up by a Cuban ship and taken to Havana.

Our boat slipped out of Marathon in the Florida Keys around midnight, skirting the mangrove swamps until we plied the rough waters of the Florida Straits. Our skipper, having made the trip numerous times, had us safely in Havana twelve hours later. While there we visited hospitals and medical schools, learning about the urgent need for medicines and equipment. At one medical school we met with a dozen medical students from poor cities in the United States. All were there tuition-free. Their only commitment was to return to the U.S. and practice in their communities. (They would, of course, have to pass their state’s medical boards.) You’ll recall that Cuba still sends doctors to impoverished countries all over the world. They’re often the first to arrive after disaster strikes.

2016

I made my fourth visit to Cuba in April, 2016 with the U.S. licensed Grand Circle Foundation that eminently succeeded in providing authentic people-to-people experiences. Our group of twenty bright, curious, and compatible participants met with State-employed Cuban workers, self-employed workers, visual artists, dancers, and academics. Along the way we enjoyed stays in Camaguey, Remedios, and Havana, with side trips to Santa Clara, Matanzas, and one night on the beach of Varadero (as a cultural and economic shock treatment).

Frame of reference

Caveat: I am not an economist or a political scientist.

I taught Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America in my Sociological Foundations of Education classes. If there’s one theoretical framework for my analysis (with much latitude and some imagination), it is that the Frenchman’s observations enabled me to grasp and accept the positive relationship between what he called a country’s “social conditions” and democracy. After innumerable readings, I understood, at a visceral level, the dynamics behind the armed conflict in Peru, where I had served as a Peace Corps Volunteer; behind the revolution in Nicaragua, where I had done research for my book

I taught Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America in my Sociological Foundations of Education classes. If there’s one theoretical framework for my analysis (with much latitude and some imagination), it is that the Frenchman’s observations enabled me to grasp and accept the positive relationship between what he called a country’s “social conditions” and democracy. After innumerable readings, I understood, at a visceral level, the dynamics behind the armed conflict in Peru, where I had served as a Peace Corps Volunteer; behind the revolution in Nicaragua, where I had done research for my book  Nicaragua Divided: La Prensa and the Chamorro Legacy; behind other Latin American rebellions, and, maybe by extension, behind world conflict in general. Consciously or unconsciously, Tocqueville’s writings helped me to understand Cuba.

Nicaragua Divided: La Prensa and the Chamorro Legacy; behind other Latin American rebellions, and, maybe by extension, behind world conflict in general. Consciously or unconsciously, Tocqueville’s writings helped me to understand Cuba.

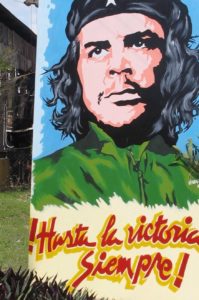

For Cubans, the social conditions that gave rise to the revolution have not been forgotten. The revolution itself still beats in the hearts of Cubans who remained on the island and in those born since. A living thing, it marches on as inexorably as the waves that crash against the cement walls of the Malecón in Havana. To understand the nearly biological ties they have to it, we might imagine the American Revolution as having happened in 1959 instead of 1776. The Cuban Revolution still has its living heroes, the greatest among them, Fidel Castro, who still gives lofty, hours-long speeches at ninety. The memory of Ernesto “Che” Guevara is fresh, as though he died last week. His remains, retrieved from Bolivia where he was executed by a Bolivian soldier, rest within a cave-like mausoleum, in an enormous square in the city of Santa Clara, where Che and his rebel fighters won a major battle against Batista forces and turned the tide of the revolution. Visitors silently pass by his tomb and the eternal flame that bears witness to his legacy.

Cubans who rejected the principles of the revolution, those fearing retaliation or execution, and those standing to lose the most under the new system fled the island, leaving a population who were loyal to Fidel. Continuing with my analogy, after having been defeated by the Patriots, the Tories, still faithful to the British Crown, left for other British territories, leaving behind true believers in the American cause for independence. These were people who had united to defeat an oppressive regime that ruled them unjustly. How easy would it be today for the descendants of those Tories to return to the United States and make demands on our economic and judicial systems? How easy would it be for them, or any outside group, to come back and dictate the terms of doing business in our country? How easy would it be for Cuban-Americans to make understood their demands upon the Cuban government?

Sign outside the Agro-industry Sugar Museum near Camaguey

To instill in Cubans the idea that the revolution was not won with battles alone, “Che” Guevara used the slogan, Hasta la Victoria Siempre (Onward Always to Victory). Revolution is on-going. The government may turn the screws on its people or open its fist, finger by finger, but it’s the government that will determine what is good for the Cuban people. We in the United States, however, want to pry those fingers open all at once. Future tourists who claim they want to visit Cuba before “McDonalds gets there” don’t have to worry. It’s unlikely that many U.S. franchises will want to do business with a government that will own fifty-one percent of all foreign businesses.

Using its five-year planning process, the Cuban State is refining its policies, like the sugar it refines for its delicious rums, but U.S. entrepreneurs, chomping at the bit to get in while the getting appears to be good, should temper their expectations. Cuba is making it easier for its citizens to begin their own businesses, but it’s unlikely that the gradual lifting of restrictions on them will mean similar favors for outsiders. The government knows how to take its share of profits to advance the course of the revolution. No foreign company can own a bank or mining operation outright, for example. The State will be the major owner. Other countries have accepted Cuba’s terms. Melia of Spain partially owns twenty-seven hotels in Cuba and has the contract to manage some State hotels, like the historic Hotel Nacional in Havana. As a University of Havana urban historian pointed out during my 2016 visit, “The United States is late to the table.”

It would be easy for a tourist who enters Havana on a U.S. cruise ship to think that Cuba has accepted full-throated capitalism. They would be deceived, even with the number of self-employed hawkers at a handicraft warehouse next to the port. These self-employed persons, known as propistas, are helping their families put food on the table, but they’re also lightening the burden on the State. There is capitalism but capitalism up to a certain point.

During my visits in 1986 and 1994, there were no casas particulars — private homes that offered lodging. There were no paladares, privately owned restaurants in private homes that sold meals to visitors, although there were a few communal restaurants for workers. There were no bicycle taxis — bicitaxis — to transport Cuban folk or shuttle children to and from school. I did see some changes, in 2002, however, when I returned with the Cuban Health Network. In the city of Trinidad, the lovely colonial town near the southern coast of the island, I negotiated three rooms in private homes for members of our group. The owners had State licenses to lease one bedroom each with breakfast. Remember the analogy of the fist. First the baby finger opens. Although our landlady was forbidden from offering us any other meal than breakfast, she did suggest that, for a price, she could provide a lobster dinner for all of us if we kept it quiet. Her son, who worked at a State-owned cigar factory, surprised us by bringing home a box of Cohibas he hoped we would buy. “The government steals from us, and we steal from the government,” he said.

Cart with attached truck modified as a bus, Santa Clara

Today bicitaxis appear to be ubiquitous except in Havana where old cars rule. Horses and carts, nevertheless, still carry people in most small and mid-size communities. The skilled driver of our Chinese-made, modern tour bus gracefully navigated around the horses and the various contraptions they pulled, most carrying people or produce. City roads are extremely narrow, making it difficult for buses, but during this nearly two-week visit, our driver never blew his horn at men peddling bicitaxis or at those with reins in their hands. The gentleness I saw in our bus driver reflected the overall impression I have of the average Cuban: gallant, generous, hospitable, and hopeful — especially after President Obama’s March, 2016 visit.

Land ownership and wealth

Tocqueville believed that the amount of land a man owned equaled his wealth. What made America different from feudal Europe were the changes in our inheritance laws that, except for some southern states, divided land among all the children after a father’s death, making ownership and wealth more equitable. Under the law of primogeniture in many European nations, all land went to the first-born son, creating vast disparities in wealth.

The question of who owned the land and how much was owned was central to the Cuban Revolution. Vast tracts were owned by a few aristocratic Cuban families or foreign-owned companies like the Texas King Ranch that you’ll read about below. Peasant farmers worked the land, cutting sugar cane for rum, raising cattle, or growing food. They lived hand-to-mouth.

It was “Che” who was at the helm of land reform after the revolution.

In 1986, the small group of educators with whom I traveled visited high schools that, under Soviet influence, had sprung up in the middle of agricultural land, far-removed from Havana. The State bused high school-aged students to these rural schools where they would remain for a term. They were doing their part to contribute to nation-building and, at the same time, learning the value of manual labor, generally disparaged by the wealthy under previous regimes. We met with students in the fields where they were picking strawberries to be shipped to the cities. They wore the red bandanas of the “young pioneers,” just as students in the Soviet Union wore. We attended their classes, and I had the occasion of being invited into a girls’ dormitory, where stuffed animals decorated beds. One of the girls asked me if I knew pop icon Cyndi Lauper. Another gave me the gift of her Communist Party pin.

While on the island in 1994, my academic friends took me by car to Pinar del Rio, southwest of Havana. We stopped at a little house where a farmer and his wife offered us refreshments. The family lived in a one-room dwelling, reminiscent of those I frequently visited as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Ica, Peru in the early sixties. There were one-inch openings between the weathered boards that comprised the walls and a well-compacted dirt floor. Family members slept in hammocks. The surroundings were Gauguin-like, with lush, dripping foliage and banana trees surrounding other equally humble houses. My friends bought some fresh fruits and vegetables from them, despite the fact that the transaction might not have been legal, given the collective nature of the farm.

In April, 2016 I noticed that all of those rural Soviet-style schools are moldering in the fields. Abandoned, their skeletons still speak to the folly of a nation allowing itself to become wholly dependent on another for its sustenance. Driven to the Soviets as a result of U.S. rejection (a reality many in the U.S. will deny), the Cuban government had relied on their Marxist friends to provide political models, infrastructure, and the necessities of daily life. The byproduct: Soviet influence in all spheres. Shortages of petroleum products led to a near economic collapse in Cuba. There was little industry, fewer cars on the road, no fertilizer, fewer farmers, and little to eat, especially little to eat. “The Special Period” marked the nadir of the ongoing Cuban Revolution, but it was this period, like nothing before, that tested the mettle of the Cuban people. They proved to be resilient, creative, persistent and, generally, loyal to their government. I tell myself that there must have been Cubans in Miami (known in Cuba as “North Havana”) who agitated for humanitarian assistance during this period. If there were ever a time when the United States could have made a positive difference, it was then.

Our 2016 group visited a little village near the King Ranch where the employees lived. There was a one-room school house, painted a soft turquoise, with a neatly-kept yard and a bust of literary hero, teacher, and poet, José Martí. Cubans on the island believe Martí to be the intellectual author of the revolution. (Cubans in Miami also claim him as their hero because of his role in Cuba’s struggle for independence from Spain.)

We met with the village teacher, who had recently been presented with a national award for his thirty years of service in the same school.

Our gracious host near King Ranch Camaguey-Province

Afterward, we entered a little house, not too dissimilar from the one I entered fourteen years ago in Pinar del Rio. It was the home of the proud lady who worked as a cook at the King Ranch. She seemed pleased to serve us coconut water and fruit in her tiny kitchen and posed for a picture before her refrigerator. There were two little bedrooms with thin bedspreads over the beds. Instead of dirt, there was a cement floor, but there were still many one-inch openings between the boards that formed the walls of the bedrooms and no screens on the wide windows that opened to a little narrow porch outside. Heads-up for would-be entrepreneurs: Cuba is in desperate need of screening material, especially with the growing risk from Aedes aegypti, the zika virus-carrying mosquito. (Earlier we had visited a colonial section of Camaguey where Cuban soldiers were going door-to-door spraying homes, oblivious to the clouds of pesticide spray coming out the doorways, where the residents waited.)

Given her humble circumstances, some of us felt uncomfortable entering the cook’s home. It turned out that she was a woman of great dignity, proud of her tidy, attractive home and proud of her job. Except for the fridge, she seemed untouched by the material world and its images that now arrive via paquetes, delivered to subscribing customers and brought to the island by enterprising Cubans. These “packages” contain thumb-nail devices that carry U.S. TV programs and movies to urban Cubans with smart phones and laptops.

Regarding the King Ranch, The Milwaukee Journal published the following news item from Camaguey on November 16, 1959: “Cuban rebel authorities completed seizure of all but 1,700 of the ranch’s 35,000 acres.” The cattle ranch, the Journal reported, was an extension of the King Ranch interests in Texas. “The land and cattle in Cuba were valued at about five million dollars.” (The King Ranch in Texas still owns 825,000 acres. According to the Texas State Historical Association, Richard King and Gideon Lewis purchased the original Texas acreage in 1853 when they bought a Spanish land grant.)

Today the ranch house and remaining acres that mainly lie fallow near Camaguey are a State-run tourist attraction — Rancho King. Buses arrive daily, carrying visitors from all over the world. Three cowboys met our bus, each carrying a flag representing Cuba, the United States, and Havanatur, the State tourist agency that employed our guide. While a trio of musicians played lively salsa or torrid boleros, we sat down at a long table with our welcoming mojitos and ate from a bountiful array of BBQ pork, beef, and chicken, along with salad, and black beans and rice, all accompanied by a fuerte Bucanero or, for those who prefer a light beer, a Crystal.

Buckboard driver with Obama sticker, King Ranch

Later we boarded buckboard wagons pulled by skinny horses to view a poor imitation of a rodeo, in which cowboys demonstrated their cow-riding skills. In another display riders would lasso a calf, jump from the horse, tie up the little guy, flip it on its side, and, after polite applause, shake the poor thing out of its noose.

Food

It appears that access to food in Cuba depends upon whether you grow it yourself or have connections to tourism. We ate like —pardon the pun — kings at our hotels and in the many paladares we visited. Hotel breakfast buffets were generous and attractively displayed. Offerings at the paladares, if not opulent, were excessive in quantity, and some offered artistically presented fusion dishes. “Parallel universe” best describes food availability on the island. Like in all matters, the State comes first. This is not to say the State doesn’t care for its people. Like a benefactor, it does distribute ration cards and one is assured of the minimum, with extra allotments of protein products, including milk, for children and the elderly, and it provides basic medical service to all its citizens. Still, there’s a world separating those who live in small towns and rural areas from those employed in the world of tourism.

State-run hotels and State-licensed paladares seem to have first dibs on the delicious produce we enjoyed in a country where so many farmers have left the land in favor of the bright lights tourism offers. Now the State offers handsome incentives to get former and new farmers back to the land after they’ve seen Havana. Our guide told us that farmers are now among the richest people in Cuba, a sea-change since my earlier visits when they worked on collective farms and might be able to sell a little surplus for their own families. Farmers can now “own” the land as long as they make it yield. If not, the land reverts to the State. Private sector farming produces 70 percent of food while State-owned farms produce the remaining 30 percent.

A professor from the University of Havana’s Center for Studies of the Cuban Economy told our 2016 group that people are willing to move back to the land, but they lack fertilizer, pesticides, and machinery. She added that State-owned farms were no longer viable. The country, she said, is still very dependent on oil, and that it needs to exploit energy from wind and solar sources. One unexpected benefit came out of the “Special Period:” After a long struggle to rebuild the soil, many farmers returned to organic farming. Now the new threat is climate change. Everyone who talked to us about agriculture agreed that Cuba is getting hotter, affecting the timing and length of the rainy season. Food production wasn’t their only concern —hurricanes are getting stronger.

The economist, who is also a member of the country’s Five Year Economic Updating Committee, reminded us that Cuba cannot buy the food it needs to feed its people from the United States because our country insists it pay in advance with dollars. Other countries offer better terms.

During the economics lecture I thought about a dear Venezuelan friend who sends me reports on the dire conditions among the people there. Venezuela has been trying to model its government on Cuba’s since the 1999 election of Hugo Chavez who remained in office until his death in 2013, just a few months into his fourth term. The policies of his hand-picked successor, Nicolás Maduro, have put the country in free-fall. At 700 percent, inflation is the highest in the world. The suffering of the people reminds me of what Cubans underwent during the “Special Period.” After the lecture, I asked the professor if Chavez and Maduro were naïve to trust in the Cuban model. She gave me a sympathetic smile but didn’t answer the question.

The five-year plan and university education

Underlying the Five-Year Plan are economic and educational concepts foreign to supply-and-demand capitalism and the self-determination of U.S. citizens. In Cuba, the State determines what kind of personnel it will need in future years to fuel its growth and development. University student openings or “slots’ depend upon the Economic Committee’s forecasting. A student may make an application to study nursing, for example, and find that all the slots are closed. That student can study in another area until the desired slot opens or choose another career track. The university is not the place “to find yourself.”

Propistas, the Self-Employed

We had several opportunities for give-and-take sessions with people from different social sectors, among them the operators of the ubiquitous bicitaxis. All the drivers with whom we met had left State jobs to work in tourism where they didn’t have to report their incomes. The spokesman for the group had been an English teacher; another, an accountant; a third, a mechanic. Although they now could provide more generously for their families, their bodies pay the price, spinal injuries the most frequent ailment reported.

The State is encouraging people to go into business for themselves but, according to a professor of urban history, “the poor can’t come to the table with nothing to invest.” They need resources before they can start a business. He pointed out, for example, that owners of casas particulars, with rooms to rent, may want to get their homes listed with Airbnb, the world-wide accommodation computer site, but are unable because they can’t afford to upgrade their houses or can’t find the needed materials. In an ironic twist, Cuba’s system of casas particulares provides the perfect infrastructure for Airbnb.

Funding of the arts

We visited several art galleries while in Cuba. Visual artists with their own studios work for themselves and rely on tourism to pay the bills. Some use their art to dissent from government policies, but they must be careful not to be blatant. One painting, for example, featured a large figure of a man with protruding forked tongues who held out his arms as though exaggerating the size of the fish painted above his head. Below him are lemming-like followers with similar forked tongues. They seem to be repeating the lies of the man above. The artist named the work, “El Gran Mentiroso,” ”The Great Liar.”

Professional dancers are usually paid by the State, however. After graduation, they audition for places in dance companies. (All education from pre-school through university is free, although preschool is free only if the mother of the child is employed.) We visited rehearsals of both classical and contemporary dance troops and had the opportunity to ask questions of them, and they of us. Most of them hoped to perform in the United States one day. As much as there is to criticize about the economy, the government supports the arts to a surprising degree.

Rehearsal at El Dedans Dance Studio, Camaguey

In Havana we met with the director of the Malpaso Dance Company. His friends and colleagues advised him against forming a private dance group, telling him it was too risky an endeavor and a “wrong step,” giving rise to the group’s name. For now the company is surviving and plans to visit the United States this summer, with stops in Cleveland, Seattle, New Orleans, Houston, Virginia Beach, Boston, and New York City. The group performed for us using the stage at the Centro Hebreo Sefardi de Cuba (Sephardic Hebrew Center of Cuba), worth exploring on their web site. The dancers held us enthralled with their agile yet muscular movements.

Members of Coro Luna, Havana

The young women from Havana’s Choro Vocal Luna, the only all-female choir in Cuba, had us on our feet. All the members graduated from colleges of music and had to audition for their places. Their young director uses only a tuning device to sound the note on which their voices rise, acapella, to create a harmony equal to any classical, contemporary, or spiritual composition. The State supports them, too.

Gifts not donations

Before we left for Cuba, the Grand Circle Foundation recommended that we bring small gifts to share with the persons we’d be visiting. At our rendezvous in Miami, the Foundation representative cautioned us, however, not to refer to our gifts as “donations” if questioned at Cuban customs. We arrived in Camaguey bearing shampoo, soap, aspirin, tooth paste, granola bars, and school supplies for children. We pooled our gifts at the start of our tour, and our Cuban guide prepared bags of them, sorted by appropriateness, for the recipients. (A good friend, who had traveled to Cuba earlier, took reading glasses. The middle-aged and older recipients were profoundly grateful.)

After learning we’d be departing our hotel in Remedios after our third night, a young, remarkably talented musician whispered in my ear, “Do you have anything to sell?” I asked her what she had in mind. “Oh, you know, like shampoos and soaps.” Asking her to wait, I hurried to our room and retrieved two large bars of fragrant soap I had brought with me. “Can I pay you?” she asked, not assuming anything. “Of course not.”

Currencies

During my 1986 and 1994 visits, Cubans seemed to covet U.S. dollars. During the “Special Period” the Cuban economy dried up and people went hungry. Among the slides a University of Havana urban historian shared with us on this trip, for example, were two of himself and his wife. In the first, the couple is standing at the ship’s railing during a Mediterranean cruise, looking fit and happy. The second shows them at table, much-changed, looking thin, gaunt and underfed. The trials of this period were further exacerbated by the ongoing U.S. embargo. The Cuban government responded by introducing excessive Cuban pesos that continued to lose value.

In 1995 the government decided that visitors should no longer be allowed to use dollars unless they exchanged them for the new Cuban convertible peso called the CUC (sounds like “kook”). Nevertheless, dollars worked well in 2002, when our small health group visited. In 2016, the economics professor with whom we met explained that the State wanted to penalize the possession of dollars because of the continuing American embargo, known in Cuba as the bloqueo (blockade). Something most Americans don’t realize is that under the Trading with the Enemy Act, third party countries can still be penalized for doing business with Cuba. In 2000 President Clinton, however, authorized the sale of humanitarian goods to Cuba (cash only).

On April 4, 2016, one CUC was worth .87 American dollars, plus the State imposed a 10 percent surcharge on the exchange. Cubans, meanwhile, still use the Cuban peso, or peso nacional, but they can convert the latter for CUCs, the more desirable currency, at a fixed rate of, at this writing, 26.5. Cuban pesos to one CUC. The government’s goal is to eventually unite the pesos.

Begging

A current visitor to Cuba will encounter a few people who will hassle you for hand-outs, something I had not experienced in previous visits. In Camaguey, a raggedly dressed woman went from one of us to another, rubbing her arms as if in a washing movement, suggesting she needed soap. In Remedios, a man playing a harmonica kept following me, trying to press into my hands the lyrics to the Cuban National Anthem, telling me that he was the composer. Although our guide recommended we not give money to beggars, she did say small items like hotel soaps, shampoos, pens, etc. would be appropriate.

Early in our visit my husband, Joe, and I spent an evening in the main plaza of Camaguey where we enjoyed watching the strutting of teen-age boys, the coquetry of young women, and the families enjoying Facetime with relatives in America thanks to the WIFI hot spots the State provides. A well-dressed elderly man — actually my age, but with more wear and tear — approached us and asked where we were from. When he told us he was from the fishing village of Caibarién, I asked him what he was doing in Camaguey. He said that he had taken the train to get there and was waiting for the 2:00 a.m. return train. He had visited Camaguey to buy medicine for his wife who had cancer, but that it was only available at the “international” drug store that takes CUCs. The man told us that he had a grown son in California from whom he has had no word in years. (Dollar remittances from the United States comprise a vital portion of the budget of fortunate Cuban families.) The gentleman didn’t fit a panhandler’s profile and seemed so grandfatherly and dedicated to his wife that I slipped him $20.00, figuring the responsibility for how he used the money was his, not mine, realizing, too, that however the money was spent, it would help him much more than it would have served us. So, yes, Cubans can still take those dollars and exchange them for CUCs, and the State will get its share, too.

In Retrospect: prospects for change

I’m reminded of the words of the urban historian with whom we met: “Cuba isn’t changing; the United States is.” The driving force behind U.S. approaches toward Cuba seems to be perceived economic opportunity, bolstered by an emerging awareness that our fifty-six-year-old embargo was a present to Fidel, in that he could rally his people against us. From my earlier trips, I remember an enormous billboard standing by the highway from the airport to Havana. It showed a small Cuban man with a megaphone, shouting across the Florida Straits at a gigantic Uncle Sam, telling him “We are not afraid of you.” The isolation we forced on Cuba sent the country first into the arms of the Soviets, and, subsequently, into those of the Canadians, French, Spanish, British, Chinese, and Japanese. The historian also reminded us that “Cuba is a process,” and he cautioned those in our group not “to look at Cuba as a snapshot.”

Earlier I told you that I use Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America as a North Star when I’m forced to think about what makes democracy work, what weakens it, and what strengthens it. In Cuba the State, as in all Communist countries, is the invisible “Father” to whom profits flow from all State-owned businesses. While the Father may open his purse from time-to-time and grant some concessions, it is he who is always in charge. He can rescind any opening if the scale is tipped against him. I liken the Cuban State or “Father” to the aristocrat in a feudal European country who has the wealth and power and decides what is best for the people dwelling in his land.

The freedoms we take for granted, like speech, assembly, and press are restricted in Cuba. Will that change? Those of us in the United States who are in favor of ending the embargo as well as our preposterously long, harmful, and ineffective side-lining of the country and its people would like to think that democracy, like revolution, is a process, that, little-by-little, the fingers of the Cuban fist will open. But we need to be realistic and find a way to deal with Cuba, at least in the beginning, in a way similar to the way we deal with South Vietnam and China. Havana is a hot-bed of economic activity, not unlike Ho Chi Minh City, formerly Saigon. There is a striking difference, however, one not to be overlooked: Cubans actually like Americans. They are, in fact, Americans.

Perusing used books in Old Havana

In 1986, 1994, and 2002, Old Havana was still sleeping, with only a few restorations of colonial jewels underway. It has since been transformed to exceed the Disney World expectations of passengers arriving on cruise ships who want to say they’ve been to Cuba. They will amble though the old streets, closed to vehicles, but they’ll have to watch where they’re going because the streets are packed. Grand old colonial homes have been re-painted in eye-popping, tropical pastels. Fern-draped, paladares offer a cool respite to hot visitors. These paladares have become restaurants for all intents and purposes.

Chess and tourists in Old Havana

If one were jaded, one might suspect that even the two men playing chess in the middle of the street were hired. (I don’t.)

Hemingway’s old haunt, the Ambos Mundos hotel, has been given a facelift and the Canadian, Cuban, and U.S. flags fluttered from its façade. Hemingway’s room is still carefully preserved. When you finish your walk, you can cool off with a generous scoop of delicious coconut ice cream from a vendor who sells it to you in a hollowed out coconut shell for three CUCs, or three U.S. dollars.

Here’s the rub

Rural Cuba is being left behind. With the influx of cruise ships and passengers, and the weight of so many tour busses, I imagine an island with sinking shores, pulling the interior down with it. I hope that someone on the Five Year Economic Updating Committee will not forget rural Cuba in its thirsty efforts to suck money from tourists for more investments in tourism. Now a wealthy visitor can even “own” a brand-new apartment in a modern high-rise with a view of the Caribbean. These architectural wonders stand side-by-side with shabby Soviet-era cement block apartment buildings. When I put the dilemma to the University of Havana economist, she acknowledged that Cuba could be reproducing the economic disparities for which the revolution had been fought. I think of it as economic schizophrenia.

Another concern is that Cuba’s population is getting older. The age demographic has dramatically shifted. Women are not having babies. It wasn’t just the urban historian who recognized the change. During this last visit I saw only one pregnant woman the whole time I was in Cuba and she was begging in a Havana plaza. Couples fear that they won’t have the resources to raise children, and they fear that there will be no one to care for them when they grow old.

And how does a nation prosper when its professionals leave their careers to crowd into the tourism horn of plenty because they can’t feed their families or advance in their professions? Even with recent raises, medical doctors with two specialties earn the equivalent of $67.00 per month, while a new nurse earns $25.00. The average state employee earns a monthly salary of $20.00. Compare that to our adept tour guide who added our generous tips to her salary from Havanatur.

Press freedom

There are three national print newspapers. According to its masthead, Granma, is the “Official Organ of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party.” Juventud Rebelde (Rebellious Youth) is published by the Union of Young Communists. And Trabajadores (Workers) is published by the Center for Cuban Workers.

On April 13, 2016, Granma re-published the following quote from Fidel, spoken on March 26, 1962: (“Granma” was the name of the boat that carried Fidel and eighty-one other rebels from Mexico to Cuba in October, 1956.)

What is the function of the party? Orientation. Orientation at every level . . .. Create a revolutionary conscience in the masses . . ., educate the masses with the concepts of socialism and with the ideas of communism, exhort the masses to work, to struggle, to defend the Revolution. Share the ideals of the Revolution, supervise, control, be vigilant, inform, discuss . . ..

(Six months after Fidel’s speech on the role of the Communist Party, I was a newly arrived Peace Corps Volunteer, sharing a school room with several other women in a barriada near Arequipa, in the southern Peruvian Andes. We huddled around my short-wave radio struggling to decipher news from the United States about the Cuban missile crisis. We feared we might never again see our families.)

In Camaguey, the driver of our bicitaxi gave me an old copy of Juventud Rebelde when I asked him where I could purchase one. On the front page of the January 8, 2012 issue I found an article commemorating Fidel’s “glorious” appearance in Matanzas after the1959 revolution. Inside that issue, I found an account by one of Fidel’s then drivers who recalled what it was like to be with Fidel when he and the “Bearded Ones” entered Havana after the “Triumph”: “The people applauded with happiness, affection, gratitude, curiosity, and admiration for our having defeated the tyrant and his professional army who were armed to the teeth by the United States.”

Race

There was much racial discrimination before the revolution, according to the Director of Teacher Training with whom our small group of educators met in 1986. She added, “the topic is still a delicate one.” In the same meeting, a Ministry of Education coordinator pointed to his springy black hair and reminded us of Fidel’s words, “Here in Cuba, everyone is a little black.” If there is still racism in Cuba, it is not apparent. Employees of every hue work together at the State hotels, and I didn’t observe any de facto segregation in the wider labor force. My impression is that schooling has everything to do with the diminishment of racism. With all the skin and eye colors represented here, terms like “black” and “white” have little meaning. To reinforce his point the education ministry representative sang the song that all children learned in pre-school:

Todos los niños del mundo

Vamos una rueda hacer y

En mil linguas cantaremos que

En paz debemos crecer.”

All the children of the world

Are going to make a circle and

In one thousand languages sing that

We must grow up in peace.

Freedom of religion

I’d like to spend time on the course of religious freedom in Cuba because I believe it to be a bellwether of other freedoms. Is there a more important freedom than that of conscience, heart, and soul and of making that conscience public? Still Catholic, but disgruntled, dissenting, and disobedient, I attended Mass during my 2016 visit as I had in 1986, 1994, and 2002, this time in Remedios, my favorite colonial city. The Church of St. John the Baptist had its origin in the late sixteenth century, but the church’s interior structure dates to the first half of the eighteenth. Its style is “Moorish Renaissance,” and it is lovely, with a glorious ceiling of painted, carved beams. The church is listed on the World Monument web site as one worthy of being cared for as an international treasure.

Many residents of Remedios traveled to Holguin to see Pope Francis when he celebrated Mass there during his September, 2015 visit to Cuba. Three hundred thousand attended the Mass in Havana’s Revolution Square that featured an enormous photo of Jesus on the National Library, not far from the image of “Che.” Francis was the third Pope to visit Cuba, coming after John Paul II in 1998 and Benedict XVI in 2012. While there Francis called for Presidents Obama and Castro to end their estrangement. The Vatican has long-opposed the U.S. trade embargo because of the harm it has does to ordinary Cubans, but, alas, only Congress can lift it.

While Cuba has traditionally been a Catholic country, the practice of religion was viewed as counter-revolutionary after the revolution. In 1986, I met up with a professor of history in a hotel bar. A student accompanied him to give him cover as it would have caused suspicions had he been seen alone with an American woman. A Catholic, the professor reported having been sidelined and ridiculed by his colleagues.

During that same visit, a State University of North Carolina professor and I met with René David, a French Catholic priest who had lived in Cuba for many years and was known for his “Theology of Reconciliation,” parts of which were published in the September 20, 1985 issue of the National Catholic Reporter. A thin, soft-spoken man with a humble demeanor, he lived at the San Carlos seminary, attached to the Havana Cathedral. Seated in an old-fashioned parlor, the priest spoke to us of his hopes for Christianity in Cuba. He said that if the distortions of communism were removed — atheism — and the distortions of Catholicism — its doctrinal rather than pastoral nature — there could be reconciliation between the Church in Cuba and Marxism. “The Theology of Liberation,” he said, “is not appropriate to Cuba because its poor have already been freed from the oppressive conditions of the Batista years, but what is needed is reconciliation.” He added, “We must be able to criticize ourselves . . .. The purpose of both the Church and the revolution is to dignify man. Errors in this process have taken place by Marxists and by Catholics. What we have in common,” he reminded us, “is the poor.”

The priest pointed out one of the errors of Marxism: “Marxists accept the slogan, ‘from everyone according to ability, and to everyone according to need,’ but here,” said Father David, “it is to everyone according to his work, and this is a weakness.” He was referring to individuals who do not have the same access to housing and health care as the majority because they have not accepted the kind of work that the government says they must accept when they cannot find jobs in their own field, or because they have not worked long enough to benefit from social security, or have been too ill to work. (This situation still exists in 2016.)

He reminded us of the parable of the workers in the vineyard. Some worked all day and complained when those who only began working toward the end of the day received the same wages. “Although this parable is a religious one,” he added, “and not political, because Christ was referring to those who come to him at the last minute, it is not abusive to use it for social purposes.” Father David said that there are signs that there will be more opportunities for Christians to worship fully. In the recent past, he said, parents were thrown out of the Communist Party if they had their children baptized. Now, he said, youths were coming to priests seeking baptism. He explained that parents were still afraid for their children to be baptized and to practice their religion because there are many teachers who have strong anti-religion feelings. Some children never hear about Christ, and, if they go to church, it is with their grandparents who explain to them the story about “the man on the cross.”

As a sign of Fidel Castro’s readiness to accept the Church and the importance of its role, Father David mentioned the publication in 1985 of a run-away best seller in  Cuba: Fidel and Religion: Conversations with Frei Betto. Frei Betto was a Brazilian Dominican brother who was imprisoned in Brazil during the sixties for his activism in social justice matters. He had extensive personal interviews with Fidel on the topic of Christianity and Marxism which began in Managua in 1980 and culminated in 1985 in Havana. In one of the interviews, that signaled a change in Church-State relations, Fidel said:

Cuba: Fidel and Religion: Conversations with Frei Betto. Frei Betto was a Brazilian Dominican brother who was imprisoned in Brazil during the sixties for his activism in social justice matters. He had extensive personal interviews with Fidel on the topic of Christianity and Marxism which began in Managua in 1980 and culminated in 1985 in Havana. In one of the interviews, that signaled a change in Church-State relations, Fidel said:

I think that Christ was a grand revolutionary. He was a man whose doctrine was dedicated to the humble and the poor in order to fight against the abuse, the injustice and the humiliation of human beings. I would say that there is much in common between the spirit and essence of what he taught and socialism.

Fidel’s disdain of capitalism, however, was more intense than ever. In his book he emphasized that “there are ten thousand more points in common that Christianity has with communism than it has with capitalism.” Fidel also praised the work of the Cuban religious who work in the hospitals and with the poor, saying, “the things they do are the things that one would hope a communist would do.”

On Easter Sunday, 1994, I took a long ride on a camelo, a public bus with two cars and finally reached a Catholic church in an outlying Havana neighborhood. The church was full. During the greeting of peace, the people embraced and welcomed me. And, during my 2002 visit to lovely Trinidad, I participated in an uplifting Mass accompanied by a soulful youth choir, accompanied by guitars at the Church of the Holy Trinity. Another finger had opened.

A Santera, waiting in line at the currency exchange, Havana

There also seems to be a renewed interest in the practice of Santeria, the African religion brought to Cuba by the slaves. Historically, Spanish priests used the African deities as a means of teaching about Christ and the saints, turning Santeria into a syncretic religion, one in which images and stories from two different religions blend. One need not look far before glimpsing a santero or santera, a man or woman dressed entirely in white, representing purity of spirit.

The Case for Respect

I believe that most Cubans are born with a purity of spirit in that they are open to life, generous, animated, optimistic, and hard-working. It would be a blow for them should U.S. Republicans prevent future overtures. The punishments our nation has imposed on Cubans are desiccated and dying. Yes, Cuba must change, but it will not dance to our tunes. Yes, it must provide for the poorest if it’s not to become what it hated before the revolution. Yes, its social pyramid is upside down, with doctors, teachers, and architects, for example, on the bottom.

When one of our group asked the economist what her wish would be for Cuban/U.S. relations, she replied that “all restrictions between our countries be dropped.” She added that we had much to offer each other. “Cuba,” she reminded us, “has made major achievements in the area of bio-technology, among them the progress it has made toward the development of a cancer vaccine and its success with cancer treatments.” The suffocating boycott that drove Cuba to do business with other countries must end, if not because it is the moral thing to do, then because it is in our own self-interest.

Cuban Pride

I’ll close with some wisdom from our winsome urban historian, who at the end of his lecture, spoke to us about Cuban pride, a concept we in the United States would be wise to acknowledge. He explained that “Cubans owe much of their pride to José Martí.” Martí inspired young and old alike with his writings on the eternal values of compassion, justice, courage, and responsibility. “Cuban pride,” the historian said, “doesn’t depend upon one’s wealth or one’s house. Cubans have it wherever they go.” As I noted earlier, Martí is as much a hero for Cubans on the island as he is for those who have left. The values he espoused in his writing are honored by all Cubans. Should you wish an introduction to Martí, please read La Edad de Oro (The Golden Age). It’s available in Spanish and English.

•

Patricia in Remedios, 2016

Patricia Edmisten is retired from the University of West Florida, where she was director of International Education and Program. She is the author of Nicaragua Divided: La Prensa and the Chamorro Legacy, and wrote the introduction to, and translation of, The Autobiography of Maria Elena Moyano, the Life and Death of a Peruvian Activist.

Her Peace Corps service in Peru inspired her novel, The Mourning of Angels. In 2007 her book of poetry, Wild Women with Tender Hearts won the Peace Corps Writers Award. Her most recent books include A Longing for Wisdom: One Woman’s Conscience and her Church, and Water Skiing on the Amazon, a memoir. www.patriciaedmistenbooks.com.

To purchase the books mentioned here from Amazon.com, click on the book cover, the bold book title, or the publishing format you would like, and Peace Corps Worldwide — an Amazon Associate — will receive a small remittance that will help support the site and the annual Peace Corps Writers awards.

Brilliant. Thank you.

Thank you, Joanne. I am so pleased with Marian’s artful design and the enthusiasm with which the article was received. As I told John, there’s still much to be said. Cuba is awash in contradictions.

Patricia

What a wonderful account of your experiences, Patricia. I could not put it down until I read it all. It will call me back to reread again and again. Thank you.

Patricia, enjoyed your excellent overview of Cuban life in all its forms; it was a great pleasure to accompany you and Joe on the “Cuba Revealed” tour of 2016. I share the concern you described in detail about the potential overwhelming pressure on the Cubans from major capitalistic neighbors [including a really close one]. Your references to Toqueville were very interesting and encourage me to give his book a read. I hope we will have a chance to visit you in FL some time.

Thank you for your kind words, Klaus. Knowing you the little bit that I do, I’m sure that you’ll really appreciate the “Frenchman” too. With every good wish, Patricia

Patricia, Your account of our trip as well as references to your other visits to Cuba gave a good context for some understanding of what has been happening in Cuba. The more I reflect on our trip the more I appreciate what an interesting experience it was. Good wishes to you and Joe.

Thank you, Bill. Traveling with you and Mary Alice enhanced our trip.

Patricia

I read this 5 years later, and with the change in Washington to President Joe Biden, perhaps the more positive aspects of Cuba as described in this wonderful article will be again emphasized by the US government. Wouldn’t it be nice if the improved relations can be re-implemented, as they were under Obama. Dick Winslow, RPCV Peru 64-66.