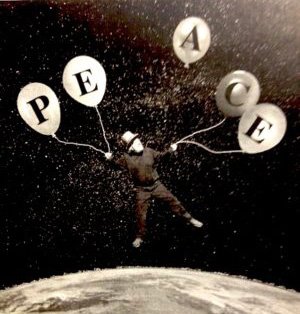

“The Road Taken” — Hank Fincken (Peru): Fulfilling the Third Goal of the Peace Corps

The Road Taken

by Hank Fincken (Peru 1970-72)

•

In June of 1970, I arrived on the coast of Peru a week after the worst earthquake in the country’s modern history. What a beginning! I saw PCVs at their finest; delivering aid, and I saw the military government at its worst, confiscating supplies — although it took me almost two years to know enough to talk about it.

My Peace Corps work was with el Programa National del Arroz. Our goal was to make Peru self-sufficient in rice, no imports necessary. Because rice is a twice-a-day staple, self-sufficiency would provide huge national budget relief. We succeeded and then we didn’t. To tell that story I would need to know that my readers suffer insomnia. I enjoyed the outdoor work, the people and the irregular adventures.

For example, in early December, my Peruvian co-worker and I were sent to the village of San Gregorio in the Andes, a ten-hour dirt road ride in the back of a truck. At the time, the U.S. government was angry with the Peruvian leftist military government for taking land from the rich and giving it to the poor. That made the locals suspicious of volunteers like me.

We didn’t exactly ride to San Gregorio. More accurately, we bounced. I arrived tired and sick: Sorroche (altitude sickness) meant I staggered out of the back of the truck and threw up.

The town was celebrating a religious holiday. Alcohol-infused festivities had begun the day before our arrival, and much of the male population was sloshed . . . including the town sheriff.

Although we had never met, he knew my occupation the moment he saw me: CIA operative. He took me to his office for questioning. On the way, I threw up again.

My Spanish was like the national budget: inexplicable. I knew the sheriff wanted me to confess to something, but I wasn’t sure what. He explained. “You’re a spy and the proof is you won’t admit it.” Twelve hours of drinking also proved it. I was too sick to argue and begged him to just shoot me. Fortunately, he felt a one-man firing squad was too good for me. He locked me up instead.

The sober men were mortified. They entered the sheriff’s office and awarded him a drink for a job well done. They then stole his keys, turned him around, and snuck me out the front door. I was loaded (not as much as the sheriff) onto a mule and escorted to the next town. Butch Cassidy would have been proud.

Never before or since have I been rescued from the police by locals who thought kidnapping was the best alternative. What courageous people! I owe my life to the towns’ disregard of authority! This was the seventies. For the first time in Peru, I felt right at home.

I don’t know if San Gregorio remembers me, but I remember the residents. Because no guns were fired, the story is funny, not tragic. Isn’t that usually the case?

After the Peace Corps, I went to Indiana University in Bloomington. I studied Theatre and Creative Writing. It took me a while to adapt to the strange local customs. For example, to publish a short story, you had to mail it at least twenty times, one at a time. There are rules for the unfamous and rules for the famous. In Peru, you might find a great story in your Sunday newspaper, and you might even know the guy.

The most important lesson I learned in Indiana is something I already knew thanks to the Peace Corps. If I wanted to get something done, I had better do it myself. When my first novel won two awards but was never published, I started writing one-man plays. History and theatre were important in those good old days, and soon I was touring the state and then the Midwest with eight original one-man history plays.

As Francisco Pizarro

I picked people who were/are controversial. Who we are is when we are, so I wanted the audience to understand the person but also the ambiance of his time and place. Francisco Pizarro, for example, was extremely brave and extremely brutal. He forces us to rethink the American ideal of having a dream and doing whatever it takes to achieve it.

When I performed Christopher Columbus for the first time in 1992, I got complaints that I was tearing down an American hero. Today, audiences (when there is an audience) is surprised that he had virtues. I have performed these one-man plays throughout the USA, Canada, Peru, Guatemala, Honduras, and Spain. I use the audience in all of my performances, so the Spanish I learned in the Peace Corps has proved essential.

History is not considered as essential as before. The lack of demand has pushed me more towards retirement than age or health. I fear we teach the history of atrocities, which is almost as incomplete as the old teaching of the “world from only a European perspective.” I don’t want to condemn the past, rather to understand it. I believe we can do better these next 500 years.

Such idealism began in 1970 when I got first helped a nation heal itself. Now I return to Ecuador to teach theatre to a group of high school kids in Otavalo every July. The Tandana Foundation is the organization that sponsors my work, small but dedicated. At our summer school, STEM subjects prepare students for college and towards a job. Theatre gives them the self-confidence to take giant steps in that direction. I write short plays in English and Spanish and we put them on for the community. The kids shine, their parents glow, and as all PCVs know: I am the one who learns the most.

•

How did you fulfill the Third Goal in your life and career? Send me your story so we can show the way RPCVs have made a difference in the world. Thank you. — John

Hi, Hank!

Cliff, I always enjoy reading about your success. Do you know what happened to Phil Appleman? We wrote back and forth for years and then suddenly I heard nothing. I really admired him.

I like this jumble of narrative in the way it is a stream coursing over a rocky river bed. And this squib from the essay here I can understand: “I fear we teach the history of atrocities, which is almost as incomplete as the old teaching of the “world from only a European perspective.”

Thanks, Edward. When I do my plays, I try not to tell the audience what to think but rather give the people more background information so they can draw their own conclusions. Lately, I have become more interested in the history of how we tell history.

I loved and needed the humor in your introduction.

Patricia (Peru, 1962-64

Patricia, Thanks! You made my day. I think one of the great joys of my Peace Corps experience is the friends I made and how they are still my friends. I have gone back twice to my Peace Corps site and seen that they were so excited that I cared enough to return. That too must be part of our RPCV responsibility.

Hank,

This is a great story! As all the Third Goal stories published here do, there are so many questioms and so many avenues to pursue.

I have three questions to start,

1) What happened to your counterpart who went with you to San Gregorio?

2) This was close to the time of the Shinning Path in the Andes. Did you ever encounter them or their allies? Or do you think they were an influence, at all, in your adventure?

3) What happened with your program objective: ” My Peace Corps work was with el Programa National del Arroz. Our goal was to make Peru self-sufficient in rice, no imports necessary. Because rice is a twice-a-day staple, self-sufficiency would provide huge national budget relief. We succeeded and then we didn’t. To tell that story I would need to know that my readers suffer insomnia”

This is incredibly important. Are you familiar with the Cornell intervention in Vicos? They returned in 2002 or so to evaluate the success of the green revolution. The conclusion was HIgh risk/ high gain, but, the risk ultmately almost destroyed the village potato crop. We posted the article and its links here at PCWW. If you put Peru Potatoes in the search box, here, the article and links should come up. It would be so good to get your opinion.

Thank you for all you did and are doing.

Joanne; My only complaint with your questions is I could write forever and not fully answer your questions. In case you didn’t notice, I have a big mouth and am constantly trying to answer questions that can’t be answered.

Question #1: My Peruvian friend and roommate had accounting responsibilities and so he left me to get his own work done. Remember, I was sick so I don’t know if he even noticed that I had been taken away by the Sheriff. He remained my friend and in fact, I went to see him last January. Sadly, he is getting old and slowing down. (I AM NOT DESPITE THE VICIOUS RUMORS THAT YOU HEAR.) . Let me catch my breath and then go on… Our friendship was one of my great experiences in Peru. He was a survivor by whcih I mean governments changed but he still found jobs. He adapted. He had certain accounting skills that were always in demand but he had to hustle

Question #2: I married a Peruvian so I returned once every three years to Lima once my now ex-wife and I finished grad school and could afford to go to Lima. During my years of service, Shining Path did not exist. Later, they were hugely influential, not on my work (I was in the states) but in the life of everyone in Peru. There are too many stories to tell. I think the Shining Path better understood the problems of the rural poor than any other organization or movement, but their solution was to be through violence. In my PC town, long after I was gone. they executed the mayor who was also a school principal in front of his students. As I understand it, they killed him not because he was corrupt but because he was slowing down the Revolution. I lost all respect for Shining Path when I learned this. Even if he was corrupt, that was wrong. And from what I heard, he was beloved, not corrupt.

Question #3. I do not have a study to back up my impressions but I do know a couple of facts about the Rice Program. We worked with the International Rice Program in the Philippines. They sent over many varieties and we tried them in different field situations. My observation: every solution seems to create new problems. So, the faster-producing rices worked better when the rains in the Andes were for a shorter duration, but they also created new problems with birds that loved an early harvest. During drier years, the traditional varieties produced at least something. Then the surprise of surprises, Ecuador figured out how to produce similar yields for less. They could undersell the Peruvian rices. That is why Peru became self-sufficient and then wasn’t.

I know PC tried some experiments with the potato and PCVs in the Andes the second year of my time in Peru. I don’t think it turned out so well, but my thoughts on why are based on hearsay. I will try to find time to read your suggested articles. Thaniks for your interest. Hank

Thank you so much. I appreciate all your further descriptions. There is so much to learn about Peace Corps work.