Finding Moritz Thomsen (Ecuador)

By Patricia A. Wand (Colombia 1963-65)

Published in Peace Corps Writers & Readers, May 1997

“THE MESSAGE FROM ECUADOR TODAY IS: NO GOOD DEED GOES UNPUNISHED.”

So wrote Moritz Thomsen on June 29, 1990, and what he meant was that he was angry at me. He was angry because I nominated him for the Sargent Shriver Award; because I suggested his traveling to the U.S. when I knew of his frail health; and because I described his living conditions in my letter of nomination. But this all happened after I got to know him a bit. Let’s start much earlier than that; when I read is first book.

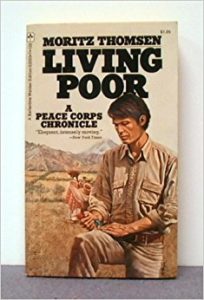

Living Poor: A Peace Corps Chronicle spoke to me and for me. Moritz Thomsen captured the essence of Latin American village culture as I too knew it. I saw in his village the same people, the same breadth of character, the same values at work as those I saw in my village in Colombia from 1963-to 1965. Never mind that the villages rested hundreds of miles and two countries apart, his on the coast and mine in the mountains. Thomsen provided insights on my villagers as though he himself had known them. Living Poor was a book I couldn’t put down and a book I never wanted to end.

By the time I finished the book I knew I had try and find Moritz Thomsen while I was in Ecuador in 1989. Shortly after arriving there, I began to ask around. Mostly I asked North Americans in Quito, Portoviejo, and Guayaquil. Did anyone know if Thomsen were still alive? Did anyone know where he lived? Did anyone know how to contact him? Did anyone know him?

I learned that he lived in Guayaquil, that he was 74 years old, a recluse, and in failing health. The Peace Corps Volunteers I met were the most helpful. Though none of them had ever met him, one told me that if I went to Guayaquil bookstore, Liberia Cientifica, I could ask the owner for Thomsen’s address.

The day I arrived in Guayaquil, while asking where I could buy a city map, I was serendipitously directed to the bookstore, Liberia Cientifica. It was a larg, busy place, lots of books and lots of people. Books lined the walls to the ceiling, and abounded on shelving throughout. A large cashier island was located in the center, close to the door, and near it stood a tall man who could easily be identified as a gringo.

After buying a map of Guayaquil, I approached this man, asking him if he was the owner of the store and told him I wanted to reach Moritz Thomsen and asked if he could help me. “Why would you want to do that?” he asked. “He’s just living in his past, not producing much anymore. His writing isn’t really worthwhile, mostly autobiographical stuff that no one wants to publish.” I responded, “I have read only one of his works, Living Poor, and I found it powerful. I don’t know about this other work. But I would like to find him and tell him how I appreciate that contribution.”

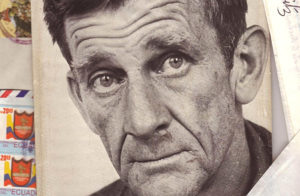

The owner called over one of his employees and asked him to accompany me to Moritz’s apartment. As we walked along the narrow sidewalks and crossed the busy streets, I thought about the intensity of the heat and humidity in Guayaquil. After turning onto Luque Street and passing several stores, my guide opened door on our left, and we entered a stark, dark stairway. Slowly we climbed three flights of stairs. On each floor there were two apartments, one in the front of the building and one in the rear. We came to the top of the stairs and knocked on yet another unmarked door leading to the front apartment. There was a pause and a shuffling as someone approached the door. A slight old man with disheveled gray and a stained, unbuttoned shirt opened it. He was not smiling and I caught a glimmer of apprehension in his eyes. For a fleeting second I wondered if it didn’t frighten him to open the door to an anonymous knock. But mostly his face revealed restrained and controlled emotions. When I saw him, unidentified and unintroduced, I wondered if this could be the man who wrote the book.

He must have immediately seen that I was harmless, being a smiling, gray-haired gringa in my 40’s and accompanied by an Ecuadorian whom he surely knew from the bookstore. So I introduced myself and said I wanted to than him for writing the best book about my Peace Corps experience that I had ever read. He smiled a soft, gentle smile and invited me into his apartment. Thus began a series of visits—seven in all—during the ten days of my stay in Guayaquil. Often I took him lunch, or flowers, and each time I stayed an hour or so. Our contact continued with several cherished letter exchanges until his death in 1991.

WHEN I LEFT MORITZ THAT FIRST DAY, I KNEW I WANTED TO SPEAD AS much time with him as I could. Partly I felt he wanted company and selfishly I knew I wanted to get to know him. Yet I did not wish to invade his privacy or make a pest of myself. I knew I could learn from his keen mind, insightful observations, and his trust in intuition. Beneath that thin veneer of cynicism was an extremely sensitive, generous man who had much to teach and was an extraordinary writer. His writing was the outlet for a soul that was deep and rich, and his façade of negativity provided him only slight protection from the pain of the world.

We always found things to discuss and sometimes the 45 minutes I intended to say became twice that. He talked about his life and his writing and I talked about me and why I was in Guayaquil. We talked often and a lot about books. We talked a about his books and about our favorite authors and about what was being written and read by whom and where. It was astounding to me how much he knew about the writing and publishing world I the U.S. and Europe even though he had spent most of the previous 25 years in Ecuador. He cited authors I had never heard of and he had read all of their works. One author who came up in our discussion early on was Barry Lopez. I spotted Arctic Dreams on Moritz’s bookshelf and asked him about it. Then I told him that, living in Eugene, Oregon, I was familiar with Lopez’s work and in fact had talked with him several times since he was an avid user and friend of the University of Oregon Library where I worked. Moritz had read everything published by Lopez and considered him one of the best nature and travel writers of our time. He called his work “ecstatic.” I too was a fan of Lopez and it seemed surreal to encounter his titles on the dusty bookshelves of a Guayaquil apartment.

Moritz also knew Wallace Stegner and Paul Theroux, whom he had met at different times when they were in Ecuador. Obviously he cherished his conversations and correspondence with both of them, and he thoroughly enjoyed reading their works. He could talk at length about each of their titles, comparing them on content and approach.

Seeing the books that surrounded Moritz made me wonder how he had acquired them. But in the course of our visits that question was answered. He had a broad network of followers, friends, and supporters in Ecuador, the U.S. and Europe.

Over the years, being an expatriate who made a name for himself through his published work, Moritz attracted various writers and visitors to Ecuador. Perhaps it was his curiosity that caused him to open his door to unannounced visitors and then to generously invite them into his life. In any case, his openness paid off in a bountiful supply of books and literature being sent to his mail box and faithfully delivered to his door via Liberia Cientifica employees. On that first visit, when he learned that I had read only one of his books, he pressed upon me a copy of his second book, The Farm on the River of Emeralds, and told me to read it and let him know what I thought. He seemed genuinely to care about my opinion. I did read it, hurriedly because of my own teaching schedule, and it gave me rich background on the Moritz-Ramon relationship. I told him that the book built on the insights into Ecuadorian culture that he had handled so well in Living Poor. And, for me, the book offered more about Moritz, what drove him and why he made the decisions he made.

His third book, The Saddest Pleasure, was then being published by Graywolf Press and he had just received a rejection letter on the fourth book, My Two Wars. (This book was published posthumously by Steerforth Press in May, 1996.) He was feeling depressed about that. He said the editor told him that in order to publish it he would have to delete a number of pages about his father, maybe as many as 20, and, in Moritz’s words, “that would be like castrating the whole story.” He explained that the book as written was essential to his well-being because it allowed him some catharsis for the terribly bitter relationship he had with his father. He wanted me to read several pages of the manuscript that the publisher found objectionable to the editor. I suspected that the decision was based solely on economic factors, the editor not being convinced that the amount of autobiographic information in the book would attract an adequately large market to justify publishing it.

When I walked in for my second visit, a very pleasant American woman was seated at the table in the visitor’s chair that I had occupied the day before. Moritz introduced me to Mary Ellen Fieweger who had flown into Guayaquil from Quito to visit him for the day. I learned that she was a faithful friend who had gotten to know Moritz when he lived in Quito and she visited him every few weeks, checking in, discussing his writing, bringing him books, food, and looking out for his well-being. I judged her to be the closest thing to family that Moritz had and I communicated with her myself several times after our introduction.

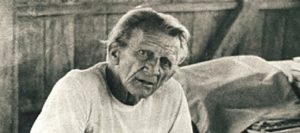

ALTHOUGH THE ECUADORIANS SAID THE APARTMENT WHERE MORITZ lived was on the second floor of Luque 507, we would call it the third floor. Moritz, was advanced emphysema and trying hard to keep himself to two cigarettes a day, found it difficult at 74 to climb the stairs. He told me he left the apartment and went down to the street only about twice a week.

The apartment was one large room with a small sleeping alcove that was just large enough for a cot surrounded by mosquito netting, a tiny closet-size kitchen, and a bathroom. Several of the walls were lined with bookshelves, all piled high with dusty books. On one side of the room was a long table where Moritz worked and spent most of his day. He placed his chair at the end of the table, new to a window, where he could look down on Luque Street or face h is guest or work at the table, whichever he chose. The table was mostly covered with books, periodicals, papers, correspondence, and his portable, manual Underwood typewriter.

I asked about the typewriter, inquiring if that was what he used to create the masterpieces he wrote. He assured me it was, that all the better, higher-grade, typewriters he had ever owned had been stolen by Ecuadorians along the way, and that this one was “so bad even the thieves did not want it.” Again I dismissed his cynicism and I marveled at his perseverance and creativity. Truly he was driven to write, whether in longhand on lined pads or using a clunky old manual typewriter.

MORITZ TALKED OFF AND ON ABOUT HIS GOOD FRIEND RAMON AND about his deep disappointment that their relationship had gone sour. He felt he had made a tremendous difference in Ramon’s life, getting him out of the village and helping to set him up on the farm. He was deeply wounded that Ramon had turned against him and that Roman “had been robbing me for years.” But Moritz derived great pleasure from the visits of Ramon’s former wife and his children who were in close contact with him.

One day I suggested that, since he considered his books some of his “best friends,” he should clean and care for them better, thereby prolonging their lives. Each one I picked up had dust and mildew on it. He said that cleaning them made him sneeze, but he offered, “I dust one off every time I pull it out to read it.” I explained that as a librarian, I was concerned about preserving books and it bothered me to see the dust gathering on his best friends. I suggested he do a few at a time and in the course of a couple of weeks all the books would be clean. Some weeks after this conversation, he wrote me: “I dusted a book. It reads the same.” (26 August 1989). I don’t remember telling him a lot about myself but along the way he began to chide me about how hard I worked. He would often say something about how important it was for me to slow down and enjoy life more. This was a message in each of his letters; for example: “Are you learning how to relax a little?” (12 April 1991).

And again:

“Patricia, you are silly to work so hard, to so complicate your life, etc. With you I’m sure it is a form of suicide, just as smoking is suicide for so many—or whipped cream—or racing cars. Does it make you feel good to be so absolutely necessary to the running of the world. (24 November 1990)

On my last day in Guayaquil, after I had said good-bye to Moritz and promised to write and send him whatever he wanted, I went back to see the bookstore owner at Liberia Cientifica. I thanked him for directing me to Moritz Thomsen. He was critical of Moritz, said that Moritz was out of touch with the world, that he could not write anything worthwhile, and that the publishers were not interested in what he wrote.

Once again I was aghast at his attitude and said, “He may be out of touch with whatever it is that you are in touch with but he speaks to a lot of people.” He blinked and stood silent. I went on to tell the owner that what Moritz needed was encouragement and support. He responded, “Why can’t he do it on his own, like the rest of us?” I told him that humans don’t work well on their own and we all need support.

Since the bookstore owner was a primary link to mail and correspondence between Moritz and the outside world, I worried about the environment in which I left Moritz. Part of me wanted to move him to Europe, Oregon where he had attended two years of university in the 1930s and about which he had fond memories. Another part of me knew that he could never be happy outside of Ecuador, even though he complained bitterly about the negative aspects of living there.

LET ME SHARE ONE MORE LETTER OF MORITZ THOMENS’S:

“Thank you for all your good advice. May I reciprocate? Practice

safe sex; always use a condom. Don’t eat eggs, mayonnaise, green

vegatables, milk or milk products, red meat, root crops like manioc,

sweet potatos, etc. Suggest Isak Dinesen’s diet: champagne and oysters.

Read good books; read carefully Chatwin, VS Naipaul, Boyes, Robert Stone,

Barry Lopez, etc. Wash your feet every 12 hours. When invited to a

dinner at the White House do not fart in those deathly silences while

Mrs. Bush is changing the subject. Wait until everyone is laughing…

More advice on request.” (26 August 1989)

Moritz, I’d like some more advice.

In 1989 Patricia A. Wand received a Fulbright Senior Lecture Award to work in Ecuador. From 1982 to 1989, she held the position of Assistant Librarian at the University of Oregon Library. Prior to that she was Head of Access Services at Columbia University Libraries. She then was the University Librarian at American University in Washington, D.C. Now retired, she continues to work and be involved in third world projects. She has not followed Moritz’s advice.

Pat, What a beautiful profile! You found the real man in the dust and the clutter! Thank you for sharing.

Hi John, Thank you for bringing this piece about Moritz Thomsen out of the archives. It reminds me of each visit I had with Moritz in Guayaquil in 1989. Our conversations resonate still and influenced me significantly…even though I’ve had trouble absorbing his advice to “slow down.”

Mortiz impacted many of us and set a high bar for writing about the Peace Corps experience. Thank you, and Marian Beil, for encouraging others to write about our Peace Corp lives. You are carrying out Mortiz’s legacy.

Thank you, Patricia—your piece is well worth reposting. John

Had I only read this piece today, it would have been enough. Thank you Patricia and John

Patricia Edmisten

Thanks for sharing these personal experiences, Patricia. Like many great writers, Moritz sounded like quite the character. His impact lives on as does his inspiration to many other writers, especially in the Peace Corps community.

Such a moving story, I would have loved to meet him, thank you for being good to him.

He was an extraordinary writer and person.