Excerpt from UNEXPECTED JOURNEY: in Chengdu, China

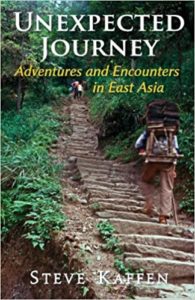

Unexpected Journey, published in 2015, described my experiences in China, among many countries, in the mid-1980s. Several essays appearing in the latest WorldView from recently returned Peace Corps/China volunteers, and Peter Hessler’s Chengdu Covid-19 commentary, brought to mind two Chengdu encounters in Unexpected Journey that demonstrate, even back then in the region served by Peace Corps, the thirst for English language education and interaction with native English-speakers. — Steve

Unexpected Journey, published in 2015, described my experiences in China, among many countries, in the mid-1980s. Several essays appearing in the latest WorldView from recently returned Peace Corps/China volunteers, and Peter Hessler’s Chengdu Covid-19 commentary, brought to mind two Chengdu encounters in Unexpected Journey that demonstrate, even back then in the region served by Peace Corps, the thirst for English language education and interaction with native English-speakers. — Steve

A Pow-er-ful Encounter

by Steve Kaffen (Russia 1994-96)

While exploring the old historic district located in the shadows of Chengdu’s imposing statue of Mao, I became lost in the maze of narrow streets crammed with wooden houses, sidewalk vendors and tiny restaurants. Turning into an alleyway, I was met by the huge brown eyes of a young boy. He smiled.

“How do you do?” he greeted me, with a British accent. “Fine, thank you,” I responded. “What is your name?”

“Fine, thank you. What is your name?” he repeated, and replied, “My name is Rong. I am twelve years old. Where do you come from?”

“America. San Francisco.” He smiled. “Where is your home?” I asked.

“Where is your home?” Repetition of the question must have been a technique used in English class. “Please come.”

We walked through the alley to his home, a one-room apartment furnished with two beds, for Rong and for his parents, a small rotating fan, a dresser with two chairs placed on top to conserve space, and a storage cabinet. On the cabinet sat the largest table radio I had ever seen, a Hongdeng 2L1400, and a yellowed Webster’s English language dictionary.

His father, an engineer with the railroad, arrived from work, nodded a greeting and retrieved the two chairs from the top of the dresser. I instantly saw the love they had for each other. The father was glad that I was here to speak English with his son. Mom arrived carrying several apples wrapped in newspaper. She peeled one and offered half to me.

The father retrieved a Chinese-English phrase book. He pointed to the question in Chinese. His son read to me the translation. He asked about work life and trains in America. Rong translated my replies.

“That is a big and powerful radio,” I commented.

The word “powerful” was new to Rong. He repeated it over and over, “pow-er-ful, pow-er-ful.” He handed me the dictionary. “Show me, please.” He read the definition aloud and looked up at me. “That is a powerful radio. I can listen to the BBC.” He explained our conversation to his father, who smiled proudly. The father had bought a powerful radio, doubtless an expensive item, so that his son would have a window to the outside world.

It was time for me to go. “Will you come tomorrow?” the father asked.

“I am not sure,” I said, which was translated by the boy. Not satisfied with the response, the father asked again.

“Yes,” I said, which the father understood without translation, nodded and smiled.

Tea House Talk

Chengdu’s tea houses in the city’s parks and gardens were ideal spots to meet the local residents. Every time I arrived alone, someone invited me to join their table.

I was scouting for a shady spot in the WuFu teahouse when an elderly man grabbed my right arm and ushered me to his table. It turned out that hello was the only English word he knew. For the next half hour, he, his wife, and I held an animated conversation using facial and hand expressions interspersed with an occasional “Hello.”

Every time I started to stand up, he motioned the attendant to refill my tea cup. I finally looked at my watch with raised eyebrows and stood up to leave. “Hello,” he said, one last time, and he shook my hand.

“Hello,” I responded with a big smile.

Happiness was finding shelter in a protected tea house moments before rain. Set on the side of a rowboat-filled lake, the Renmin Park tea house featured shiny bamboo tables and chairs under a blanket of trees thickly covered with hanging vines.

It was here, during an afternoon shower, that I met Dr. Yen and his wife. Both taught Russian at the College of Meteorology. I thought that I had not heard him properly.

“The weather college,” he confirmed. “Farmers must know what the weather will be. It is a very important discipline.”

“But why Russian in a weather college?”

“Everyone must select a foreign language. Of the two hundred students, all but ten selected English. Five selected Japanese; three, German. We teach the two who selected Russian.” He smiled. “So we enjoy lots of leisure time at the teahouse.”

•

Steve Kaffen served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Russia 1994-96, A decade later, as Assistant Inspector General and Senior Auditor at Peace Corps, he visited many posts to review their operations. Besides New York, he’s lived in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Paris, and currently Washington, DC. An independent publisher and author, Steve dedicates his books “To you, my fellow traveler, on the road and in life.”

No comments yet.

Add your comment