Encounters with Harris Wofford by Neil Boyer (Ethiopia)

Encounters with Harris Wofford

By Neil Boyer

My first encounter with Harris came in the spring of 1962, when I was a third-year student at New York University

School of Law. I stopped in the dormitory where I lived (Hayden Hall) and found in my mailbox a message asking me to call Harris Wofford. I had no idea who he was, and there was no return phone number or any other reference to anyone of that name. So I began a search of the white pages in the Manhattan phone directory, found a listing for a Harris Wofford and called the number. The man who answered was pleasant but as puzzled about this call as I was. I guessed that this had something to do with the Peace Corps since I had applied but not heard anything in return. Aha, the man said, “I think you want my son. He’s in Washington, working with the Peace Corps, and I think you should call him there.” And so, by the same white pages process, I found a number for the Peace Corps, talked to a number of people, all equally puzzled, until finally I got the right Harris Wofford on the phone.

Harris said he was heading up a project in Ethiopia for the newly created Peace Corps and he was calling all the lawyers or people with law degrees who had applied to the Peace Corps to join him in this project. As it turned out, there were only three of us in this category. He gave me a big Woffordesque sales pitch. We exchanged contact information, and he said he would have someone get in touch with me. Not long afterward, someone called and we began the process of personal identification and testing. That included a complicated application form, and my picture appeared in the New York Times weeks later showing me in a very large room full of people who were taking a test for entry into the Peace Corps.

I was told that Harris and other Peace Corps staff wanted me for a training program that would begin in early July for prospective volunteers who would go to Ethiopia. I told them I couldn’t do it since I had to take the New York State bar exam on dates that would interfere with the training program. No problem, I was told, the Peace Corps would arrange for me to arrive late, after training for Ethiopia had begun, and so I should feel free to go ahead and take the bar exam. In thinking this through much later, I concluded that Harris had had something to do with that decision, as he ultimately would for many other turns in my career path.

On the day after the bar exam, I had my first ride in an airplane, from New York to Washington., and shortly thereafter I was in a room in the large dormitory that faces the main entrance of Georgetown University. After being inoculated, inspected, trained and ultimately “selected in,” I joined the project that was then called “Ethiopia I,” in anticipation that there would be many more such projects, and there were.

After 300 of us flew to Ethiopia, many of us took up temporary residence in a dormitory at University College at Arat Kilo in Addis Ababa. There, we met the full Wofford family, with Harris, Clare, Suzanne, David and Dan, and we began local orientation. Seifu Felleke, who was the headmaster of the Commercial School in Addis, came to the college to meet the Peace Corps Volunteers who would be an important part of the staff at his school. Seifu had been misinformed about the American naming system and so he reversed or double reversed the names of his first volunteers as he called them out for greetings: Boyer Neil, Fisk Samuel, Coyne John, Crawford Charlotte, and Socha Wanda. Over time, we gently tried to re-orient his perception of our names.

I had agreed to teach English at the Commercial School since Harris had not yet been able to develop an assignment for volunteers trained in the law, but he promised to keep working on it. Halfway through the first school year, he found a legal job for me, although it was not full – time. I would teach English half time to sophomores at the new American-staffed Business College of Haile Selassie I University. In preparation, I recruited John Coyne to come to my English class to make a special presentation on creative writing, which turned out quite well. I would also do legal work at the Institute of Public Administration, under the supervision of Don Paradis, an American who was legal advisor to the prime minister. Harris worked with Don to ensure that I had a meaningful job related to my law-school education. I was first asked to write a paper describing the Ethiopian court system for use in orienting the American teachers just then arriving at the new university law school that would be headed by Jim Paul. I wrote the paper, gave it to Don Paradis, and forgot about it. Bad idea!

That summer, after the public schools completed their sessions, many PCVs embarked on vacation travel around the region. Charlotte Crawford, a fellow teacher at the Commercial School, and I organized a wonderful trip by plane, cargo boat, taxi and whatever travel means we could organize. We went to Djibouti, Egypt, Lebanon, Cyprus, Jordan, Syria and Sudan. Among other things, we unexpectedly met half a dozen other Ethiopia I volunteers at a rooftop restaurant in a Cairo hotel, and we saw PCVs from other countries along the way. The Peace Corps was new but volunteers already seemed to be everywhere.

Our trip culminated in a flight from Khartoum in the Sudan back to Addis. As the plane pulled up to the terminal in Addis, we looked out the window and there we saw Harris Wofford waiting for us at the bottom of the stairs. How nice to be welcomed back from vacation! Well, that was a misperception. Harris was not there to welcome us back but to tell me that the Foreign Ministry wanted me thrown out of the country! Surprise! Apparently, my paper on the Ethiopia court system had been somewhat indiscrete, if not rude, and it had been seen by government officials who were not pleased. Harris and I talked for a short time. He didn’t give me details, but I knew the Peace Corps had already been through the Marjory Michelmore Postcard Incident and didn’t want a repeat. Harris apparently had been designated to do clean-up. I’m sorry that I can’t finish this story since I don’t know what Harris did to fix things. He told me to go back to my English class at the University on Monday morning, and I did, and I never heard another word about the incident. Harris clearly had influence.

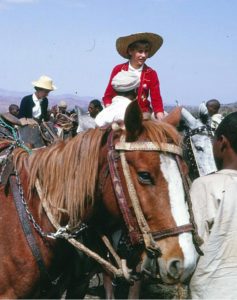

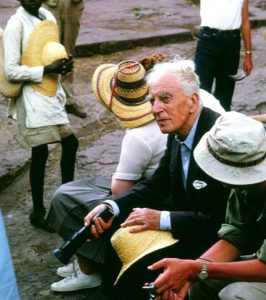

One highlight of our time in Ethiopia was a visit to Lalibela, the ancient town of red rock-hewn churches that is on the must-see list of many tourists to Ethiopia. We flew from Addis in several small DC-3 planes that landed on a rough unpaved field near the town. We landed near the town but not near enough since we then had to mount donkeys that had been waiting for us. Harris didn’t join us for this excursion, but my photos of the group show Clare and Suzanne Wofford and a number of Ethiopia I volunteers, staff and family members in the town. Among the group that day was the distinguished historian Arnold Toynbee, and it was a pleasure to ride next to him up the hill to the little town.

As we boarded the plane for the return to Addis, the pilot understood that the narrow dirt runway was almost

overrun by young kids who would block the path for the plane to exit. But the pilot has a solution for that. After the plane taxied to the far end of the runway for take-off, an airport employee (the copilot?) jumped out and ran off with a bag of candy (caramelos, I think they were called). Then he threw the candy into the bushes. The kids followed, trying to get as much candy as they could, and when they were out of the way, the plane took off. Very clever. On the way back, I turned to Peace Corps staffer Bill White, who was seated behind me, to ask if he also saw smoke coming out of the starboard engine. Without looking, he confidently told me he didn’t see a thing. Good staffer!

After two years in the Peace Corps, many PCVs went home to look for jobs and many on the East Coast went to the Peace Corps headquarters in the Maiatico Building on H Street, across Lafayette Park from the White House. Here was more of Harris’ influence. By the time we arrived in Washington, Harris had left Ethiopia and been named Associate Director of the Peace Corps. A lot of RPCVs were working there, including some who had been in Ethiopia. Harris’s office was the “home port” for many of them. Former volunteer Sally Collier served as administrative assistant for Harris, and part of her job was to keep order, never an easy task with Harris. One day, when he was out, about a dozen former volunteers were scattered around his office, on the floor and at desks, with at least one of them in Harris’ chair. A senior staff member stuck his head in the door and was taken aback when he saw all these young people (most of us still in our 20s) working in the office and asked “What is this? Boy’s Nation?” Some, more senior, staff members were in and out of that suite all the time. I especially recall Alex Shakow, Dan Sharp, Dave Schimmel, and of course Joe Colmen, who shared the suite with Harris as his deputy. Joe was a merciless, sharp and funny critic of the PCV coterie.

Many former PCVs who had come to in Washington were dispatched on speaking trips, charged with extolling the virtues of the Peace Corps, especially to college audiences. Harris asked me to join him in speaking to what I recall was a group of a couple hundred young participants in Henry Ollendorf’s Cleveland International Program (CIP). I think this group may be what gave Harris the idea of a “reverse peace corps” that would bring young people from other countries to live and do projects in America. (But knowing Harris, I think he and not CIP may well have been the first to get this idea.) Not too many years later I would become director of this reverse peace corps program.

Harris and I did the presentation to the CIP group in a large room at the headquarters of the U.S. Information Agency, on the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 18th Street, across the street from the Roger Smith Hotel. (Both the USIA building and that hotel are long gone.) Harris talked to the group about the Peace Corps goals and philosophy, and then he introduced me as a living example of someone who actually had gone out for two years and come back. There was a good discussion involving Harris and me and the young people, who were very interested in the Peace Corps idea. After the event, an attractive young lady from Finland pursued me around the hall asking further questions, and at the end of the day, we left the building together. I don’t think this is what Harris had in mind.

I first worked in a small office under Harris’ supervision charged with encouraging and helping other countries to create and operate voluntary service programs, whether domestic or international. We coordinated our role with Bill Delano’s International Peace Corps Secretariat, which had basically the same goal. (Yes, it was a duplication of effort.) We hosted meetings with officials of voluntary service programs in England, Germany, Argentina, Australia, Israel, the Philippines and other countries, sharing experiences and hoping to increase the number of people and agencies promoting service. In a related move, Harris played a major role in creation of Ethiopian University Service, which sent students at Haile Selassie University out for projects in the countryside and elsewhere. The students were not always happy to have this diversion from their studies, but at the end of the program many said they were grateful for the experience.

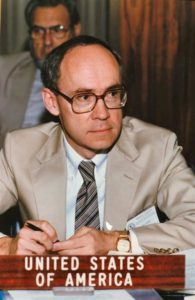

During this time, there was a major effort to reform the American Selective Service System. Many felt the draft discriminated against low-income people who could not afford to go to college and get educational deferments. President Johnson created the National Advisory Commission on Selective Service in the hope that it would create new ideas for staffing the military. Harris, looking for new service opportunities, as always, arranged for me to serve on the staff of Burke Marshall’s commission, primarily so that I could encourage consideration of Peace Corps service as an alternative to the draft. There was a groundswell of support for this idea, especially among young men who were not happy about the prospect of going into the army. I wrote a paper for the commissioners explaining the value of voluntary service. The commission was a very diverse group. It included Kingman Brewster, the president of Yale, several social workers and clergymen, and David Shoup, the retired commandant of the Marine Corps. Harris talked with many of them to promote the voluntary service idea, but it was of little value at the time. Shoup was very outspoken and told the commission that allowing Peace Corps and other voluntary service to be an alternative to the military draft was the dumbest idea he’d ever heard. Someone had suggested that the non-military volunteers could serve at home as teachers’ assistants, including helping young kids put on boots and snowsuits in the winter. Shoup thereafter referred to this as “that snowsuit program,” and that was the end of it. When the commission was finished, it recommended a lottery system for the-draft. A young man wouldn’t be called up for service until his number came up. In time that was There was a lot of support for that approach, and it was then provided for in legislation.

In the meantime, Harris had been working on the creation of a “reverse peace corps” that would bring teachers, social workers and others from other countries to do work and serve in America as volunteers, literally the reverse of the Peace Corps concept. New ideas of service were never far from his mind. He arranged for me to leave the selective service commission to move to the Department of State to implement his idea of “Volunteers to America.“ Dave Schimmel had already made a start on defining the job. I spent the next two years implementing Harris’ idea, shepherding selection, training and supervision of young volunteers from abroad through subcontractors and direct action. Later, we were able to move the program out of the State Department and back to the Peace Corps, where it had begun in Harris Wofford’s office, and Kevin Lowther took it over. But, like voluntary service as an alternative to the draft, the idea of adopting new legislation to establish a reverse peace corps within the Peace Corps produced an outpouring of right-wing conservative criticism. Why do we need another Communist program, one legislator asked. A few members of Congress then ensured that the program would end and could not be resurrected later.

Nevertheless, this idea still had many strong supporters. Many articles were written about it and it has been discussed in a number of books. A substantial number of documents – brochures, diaries, photos, and evaluations of the program have been donated to the library at American University to aid future researchers.

Harris’ ideas live on. So too do the many service programs that have Harris’ fingerprints on them. He didn’t create or operate all of these programs, but he was close by. There was VISTA, Dick Graham’s Teacher Corps, the Job Corps, Teach for America, AmeriCorps and a large number of small private programs that promote voluntary service. All offered benefits for the participants as well as for the receiving agencies, i.e., the third goal of the Peace Corps. My son, Gary Boyer, is an example. Sometime after he completed college, he volunteered for AmeriCorps and worked in the mountains near Asheville, North Carolina, helping low-income people get better insulation in their houses for more comfort and less expense. Today, ten years later, he is a project manager for Edge Energy, using skills he picked up in AmeriCorps, and performing at professional levels.

Harris’ legacy moves on. Almost no part of voluntary service in America has been untouched by his philosophy and ideas.

Neil Boyer was a member of the first Peace Corps volunteer group to serve in Ethiopia, 1962-1964. He retired from the Department of State in 2003. He is married to Johanna Misey Boyer, a medical social worker, and they live in Silver Spring, Maryland. Neil is the father of two children, Sabrina Boyer Foster and Gary Boyer, and he has four grandchildren.

When I trained PCTs at NYU for service in Turkey in the summer of 1966, my second project with the school, our PC Rep from Washington told a story of how Harris, being concerned about the absence of low income minority recruits from the Black Belt came up with a scheme of using what were perceived to be “Southern Black” common first names, e.g. “Bubba,” in an effort to seek them out and recruit them. However, those recruited turned out to be largely White. Does anyone else know about this effort?

Wonderful recollections Neil with great memories of Harris and Claire. Charlotte has regaled us with stories of your summer and end of service travels. Harris made it possible and invigorating for all of us. Bill and Maggie Donohoe. Ethie 1’s

Hi, Bill. Thanks for the note. Glad to hear you are still in touch with Charlotte. Regards to both you and Maggie.

Wonderful piece on Harris, Neil. Weren’t we all so very lucky? I didn’t know that Harris also kept you from being booted out of the country. I’m glad to hear I wasn’t alone in that dubious distinction.

Sounds like you have a story of your own that needs preserving.

A wonderful piece, Neil, illuminating some parts of Harris’ legacy that I was not familiar with. I was a bit of rebel sympathizer up in Eritrea. I wonder if Harris didn’t save my ass at some point, also. I’m sure we all kept him busy!

I think I was one of the RPCVs who met you and Charlotte in Cairo. I had just finished a course in Arabic taught by a Kagnew Station interpreter/spy. I think Tom Gallagher was traveling with us and he became quite good in the language. I returned to a part of Ertirea where no Arabic was spoken. When Arabic-speaking travelers stopped in our town on buses, I was the unofficial Arabic-English translator.

Great times, great memories. Thank you for your service.

A lovely piece, Neil. We, among many others, I am sure, are honoring Harris at our annual Global Camps Africa event in April. He was on our Advisory Council. We’re in the beginning stages of the program but I assume (silence is consent!) you won’t mind if we incorporate some of your written memories. All the best!

Phil Lilienthal

Go for it!