A Writer Writes:The Lesson of the Machi by David C. Edmonds

A Writer Writes

The Lesson of the Machi

By David C. Edmonds (Chile (1963-65)

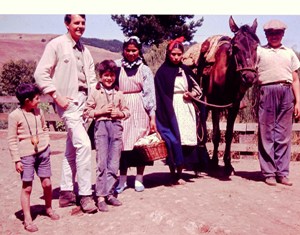

Mapuche village near Chol Chol, Arauca, Chile

September 1964

Friday-The drums wake me again. Now what? Another funeral for some poor child? A wedding? No, the village Machi, who performs all healing and religious rituals, is going to offer another lesson for the young girls. I don’t know the details because things that happen here don’t always make sense. So when I see the Machi’s seventeen-year-old daughter, Ñashay, passing by my little dirt-floor ruca with a pale of milk, I ask her what is going on.

“It is called the Lesson of Two Loves,” she tells me in her broken way of speaking Spanish, standing there on the mud walkway in her head dress and shawl, all four feet, ten inches of her.

“What is the Lesson of Two Loves?”

“Yes, the Lesson of Two Loves. Dos novios.” She holds up two fingers.”

I shake my head. Ñashay’s Spanish is only slightly better than my Mapuche, but it’s the only way I have of communicating until I learn the language better. I try again. “Does that mean a girl or woman can have two husbands? Dos maridos?”

“No, no, no. A girl like me have love like you but love another. Much confusion.”

Yes, mucho confusion. Our conversation goes on until I think I understand. If a young woman is torn between two loves, how does she resolve the issue? The subject interests me because I also have two loves in my life. I ask Ñashay if I can attend the lesson. It’s not as though I have other things to do. Like a candlelight dinner or TV to watch.

“No, no, no,” she answers. “Lesson for girls. No boys.”

“But what if it’s dark? What if I hide under a table or beneath a blanket?”

“Blanket?”

I ask the question in two or three different ways before she understands. I expect another of her “no, no, no,” reaction. Instead, she smiles that naughty little smile I’ve seen before, like when she sneaks into my ruca and asks for a cigarette. Or the first time she planted a kiss on my lips.

“Clandestino,” she said.

“Yes, clandestine.”

“We go you and me clandestino.”

“Yes, we go together. When? Is it tonight?

“Maybe tonight. Maybe tomorrow. Maybe many days from now.”

“If it is many days from now, then why the excitement today?”

“Yes, much excitement.”

* * *

Monday. Three days have passed and I hear nothing more about the Lesson of Two Loves. Maybe I dreamed it. The only thing for certain is I can never get warm in this dismal little village. Except when I’m tucked into my sleeping bag. Stomach is acting up again. Imagine I’ll have to go to Santiago before long for a check-up. Last week it was head lice and treatment with kerosene. This week a stomach ailment. Leg is healing nicely. Been more than a month since my last abdominal injection and I’m not frothing yet at the mouth.

The Machi should teach a lesson about rabid dogs.

Good news. Ñashay just came by for her cigarette and told me the Machi is preparing her Lesson of Two Loves. It could be any day now. As for her kisses, I need to do a better job of controlling the situation. These people would scalp me if I… Or worse, they could force me into a shotgun wedding. Get hold of yourself Edmonds. Think of that beautiful Peruvian girl waiting for you back in Santiago. Oh, that long dark hair and moist lips…

* * *

Wednesday– Spring has arrived. The Chileans call it Primavera, meaning “First Green,” but my Mapuche friends call it “Season of the Flowers.” Everywhere are crocus and bluebells, and the prettiest little blue and pink flowers that grow along fence rows. Green is bursting out all over. But it’s still cold. There’s also talk of politics. Presidential candidate Salvador Allende himself is coming next week to nearby Lautaro. Never seen so much excitement. Almost every barn and tree and fence post and cabin is adorned with a large “X.” The upper part of the X stands for vota (vote) and the lower part is an “A” for Allende.

A rumor is going around that he speaks the tongue of The People.

I know better because I’ve met him, talked to him once at in Los Lagos. He travels with a Mapuche interpreter. Good man, though. And what a name! Salvador, Salvador, savior of The People. I don’t blame the Mapuches. I’d vote for him, too. The current president, Jorge Alessandri and his elitist friends side with the landowners and the priests. Never brought these people anything but misery. Do you hear that, my good friends at the US Embassy? When are you people going to learn that the rotos of Chile want justice and dignity, and that a vote for Dr. Allende isn’t necessarily a vote against the US?

* * *

Monday-Still no Lesson of Two Loves, nothing but cold and rainy weather. Miserable. Ñashay helped me with my Mapuche all weekend. Such a tough language. I’ll never learn it as well as I did Íslenzkur (Icelandic). I’m just not as inspired. Maybe because I don’t have a princess like Elska Erna Armandsdóttir to teach me. It’s been several years and even with my Peruvian love in the interim, I still dream of those Icelandic blue eyes. Especially when it’s raining or snowing and the wind is howling and I crawl into my smelly sleeping bag wishing I was back in Reykjavik, sleeping under a goose down cover.

Like last night. In the wind I imagined I could hear her voice whispering, “Elska lita Davy min,” and when I awoke there seemed to be a lingering scent of Chanel in the air. Times like these I wish I could take Armandsdóttir by the hand and pile into one of those long-hulled Viking ships and paddle off with her toward Valhalla. Wonder what she’d think about Ñashay?

* * *

Wednesday, I think-The Machi must have canceled her Lesson of Two Loves. Ñashay shrugs when I ask her. The only interesting thing today was a peddler from Los Lagos who stopped by the village with his goods. He argued that LBJ was behind the shooting of JFK. I hear it all the time. The logic: Who gains the most by his death? LBJ, of course. It’s still hard for me to believe that a sleazy little misfit like Lee Harvey Oswald could wind up in the history books. Lincoln was shot by a famous actor; Caesar done in by prominent men of the Senate. But LHO? I can still see him propped up on a kitchen cabinet at a party in the New Orleans garden center, trying to convince me and a couple of drunk Cubans that he spoke Russian. Incredible the reaction I get when I mention that we ran in the same circles in N.O. Like I should have been able to see his intentions.

Maybe the Machi could, but I’m just a mortal.

The man from Los Lagos also wanted to know why Americans “hate” Negroes. The suggestion got my blood up, and we had a spirited conversation with me telling him that, yes, there are bigots and haters everywhere, even in Chile. He didn’t like it when I told him that Negroes in the States have it a lot better than the Mapuches of Chile. I catch enough grief from my fellow PCV’s about Civil Rights just because I’m from Louisiana and Mississippi.

* * *

Friday already and I’m wondering why the Peace Corps sent me to such a remote place? Not a damn thing to do. Was it to show the Mapuches that Americans aren’t the demons the Communists depict us to be? Or to keep me from running my mouth about my association with LHO? They may be right. What a headline it would make for El Siglo. FRIEND OF MAN WHO SHOT JFK IS PEACE CORPS VOLUNTEER. Not so. I hardly knew the little bastard. Every meeting with him and every conversation would fill no more than a half dozen pages. Double-spaced.

Every day I sit down with pencil and paper and sketch out a plan of something productive to do. Like form an agricultural cooperative. But it’s almost impossible to interest the village leaders or even make friends with anyone except the young girls. Today I went out to talk to a little boy with a slingshot. His mom yelled at him. Yesterday I tried to help a man fix the wheel on his oxcart. His wife yelled at him. Like I was the devil. The only smile I ever got was the day I borrowed Puenkel’s horse and rode it through the village. It wasn’t a John Wayne moment, but at least it showed them that I can ride one of their horses. Hell, I grew up with horses.

Days are so depressing. Feeling unwanted. Unloved. Hated. Despised. This must be how black people feel in the US. No wonder they march for justice. Just like the Mapuches. The only way I keep my sanity is by reading books, thanks to a trunk load of books provided by the Peace Corps. I read three books this past month-a book about Stalingrad by an old Nazi, Francoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse, and a romance that inspired me to write a few more pages of Lily of Peru, my attempt at a romance about a fling with that gorgeous Peruvian exchange student.

Was she really that gorgeous? And witty and intelligent and oh, so tempting with that long black hair and the way she moistens her lips before I kiss her. Or is it that after a few months in this place that any young woman with European looks get me huffing and puffing?

I pick up one of her letters and read a few lines: I can’t stop thinking about you. I think of you when I go to bed and wish you were here beside me. I dream of you. I think of you when I wake in the morning. Do you feel the same? Please write me every day. Please come back to me. Please sit down with me and let’s work it out. All my love with a kiss.

Oh, man, what a novel I could get out of this. A poem, a song, a love dance. Boy meets girl. Boy and girl fall in love. They whisper in the moonlight and make love on a blanket beneath the Southern Cross. But things come between them-like me having to return to this dismal place. And her boyfriend back in Lima. A rock throwing radical who wants to fight for justice with Hugo Blanco in the mountains. And maybe come after me for, ahem, spending time with his betrothed.

She invades my dreams the same way my Icelandic love used to do. But unlike Miss Iceland, Miss Lily of Peru is available. I have so little to do here because of the bad weather and the uncooperative villagers that it would almost be worth it to fall ill again just to have a chance to go back to Santiago and spend time with her. Oh, Lord, forgive me for thinking such things.

* * *

Monday-Back from the political rally in Lautaro. Road a mess. Thank goodness for 4-wheel drive on my Jeep. Almost ran over a drunk Mapuche sleeping in the road. Picked up some canned goods in market and went back to Jeep to discover a string of dead rats hanging from rear-view mirror. The lesson is clear-we don’t like you. Go home.

In Lautaro I ran into other PCV’s attending the rally-John Shelly, Kirk Breed, Don Loomis, Dick Kramer. How good to sit down over a beer and speak my native language and catch up on the gossip. Unlike me, most of them are affiliated with some organization or other and are doing productive work. When they ask what I’m doing, my first thought is to say “Not a damn thing.” But that’s not true, so I tell them about my research to form a cooperative and how I’ve applied to CARE for help in starting a carpenter workshops at the local school.

_______tells me he’s voting absentee for Goldwater. He also told me that (another PCV) has been goteando fuego (dripping fire) as a result of a tumble in the moonlight with some little chiquilla he picked up hitching a ride to Antofagasta.

Another lesson we should hear from the Machi: use a rubber or keep it in your pants.

As for the rally, I’m still impressed with Salvador Allende. What an inspiration for these people. The alcalde of Lautaro fired up the crowd in his introduction by saying Don Salvador would confiscate the big landowner’s property (the hated fundistas) and give it back to the people of Arauca. Then he would nationalize all the American and European banks. And create a nation for the poor that stretched from the Rio Maule to Isla Chilloe.

When Allende took the stage, the first words out of his mouth were, “This land is your land!”

The crowd roared. He said it again and again, louder each time. The crowd responded with “Allen-de! Allen-de!” and the ground shook.

One of the landowners’ daughters, a cute little thing named Sofía, who was there with her chubby mother, heckled the speakers with words like “ignorant” and “stupid Indians” and “dirty Communists.” Amazing how they tolerated her. Turns out that she’s the girlfriend of the PCV who plans to vote for Goldwater. When I first saw her and how cute she is, I was envious. No longer. Hell, no. These poor people only want a better life for themselves. Sorry, Sofía, but I’d never kick Ñashay out of my sack for you. Character is more important than looks.

* * *

Friday-It could happen soon. The weather is nice and I’m conspiring with Ñashay on how to sneak me into the Machi’s class. Either her Spanish is improving or my Mapuche is getting better, and now we’re conversing easily in a garble of both languages.

Today I saw a jet trail across the sky. What a strange feeling. Here I am in the Fifteenth Century and see a jet trail. Maybe this is all a dream. Like Mark Twain’s CONNECTICUT YANKEE IN KING ARTHUR’S COURT.

I wish Ñashay wouldn’t look at me with those sad puppy dog eyes. I feel guilty as it is. Why can’t she get it through her head that I’m not going to stay here forever? Or get involved with her. How could I break her heart by telling her she doesn’t fit into my world?

I can imagine me introducing her to friends at a soiree in the N.O. Garden Center: “This is my friend, Ñashay Huechaquecho, Water-of-the-Earth, daughter of the Machi of Arauca. Doesn’t speak English, and precious little Castellano either, but I’ll be happy to translate into Mapuche. And what’s the significance of the eagle breastplate and the head-dress, you ask?

“Well, it’s a long story…”

* * *

Nightfall–Drums are beating. I hear the roar of the Chol-Chol, swollen by melting snows. I’m writing in candle light. Ñashay should be here any minute. “Must be careful,” she told me earlier. “Can’t let them see you. Boys not allowed.”

They’re going to sacrifice a goat, she tells me. But the word for goat in Mapuche also means a young man. Should I worry? Only four years ago, after a big earthquake, they did in fact sacrifice a boy. Cut of his hands and arms and let the tide take him away. Horror of horrors!

Dogs are barking. If they were howling I’d really be worried. It’s cold out. I’m going to dress warm. My Icelandic girlfriend would tell me to “vera gaetinn” (be careful). Haven’t been this nervous since the first day I came to this village. Sweaty palms. Dry mouth. Heart racing.

Get a grip, Edmonds! Final entry: Mom, I love you.

* * *

Sunday-Raining today. Cold. Miserable. Overnight snow in higher elevations. I’m still among the living. Night before last was enchanting but also disgusting. Both Ñashay and Micaela are with me this morning to help me recount the events for my notes. Problem is they argue a lot (sisters) and cannot always agree on sequence of events or exact words.

But we’re going to regress to the Lesson of the Machi and pick it up in present tense.

* * *

I don’t like the idea of slaughtering a goat and catching its blood. Like the first day I came here and had to drink a sip from a gourd. The thought disgusts me. They spice the drink with aji and cebollas (Christ! I can’t even speak English). Anyhow, it’s a beautiful evening. Stars bright. The Southern Cross looks so close I feel I can reach up and touch it.

Can also hear the creaking wheels of oxcarts, cows lowing in the distance, the smell of flowers and freshly turned earth. And the drumbeat, slowly at first, muted. It grows louder, more intense. The tempo picks up, (Ba-dum, Ba-dum, Ba-dum) and out from the rucas come the young girls for their lesson with the Machi of Arauca, pulling their alpaca ponchos over their heads.

I know most of these girls, but the only one I can pick out in the poor light is Puenkel’s little moon-faced daughter, she who brings me fresh milk from the family cows.

Milk I have to first pick out the flies and then boil before drinking.

Ñashay leads me to a little depression near the campfire, about thirty paces from the gathering. We’re hidden here, I think. But what will they do if they discover me?

Through my binoculars I clearly see the Machi Herself, seated before the fire like a sacred buddha, her eagle breastplate reflecting the light. The girls gather round and spread their blankets. It gives me comfort to see a few boys hiding behind a haystack, their heads popping up from time to time. Another sits high on a tree limb.

Am I the first outsider to witness such a ceremony?

Cold. A sweater and jacket isn’t enough. Ñashay runs to her ruca and comes trotting back with alpaca blankets. She leans into me on the ground as if we were lovers, but straightens up when the Machi calls her audience to attention.

From the darkness comes a young girl leading a tethered goat. A drum beats. Horns blow. The Machi prays to the spirits of the forest and the mountains in her Indian tongue. She begs forgiveness of the poor creature they’re about to sacrifice. I can’t understand her words. Can barely hear them from this distance, but Ñashay whispers them into my ear as if she’s practicing to be the Machi herself-which she probably is. The goat is placed on the flat rock and held down by three older women. It kicks and cries as if it knows what they are about to do.

Someone produces a knife the size of a Roman short sword.

A woman holds a gourd for catching the blood.

The knife comes down. I look away. I’m going to be sick. When I look back the goat is kicking. Then it lies still. The woman who slit its throat leans down and sucks out the last of the blood. She looks up and smiles a toothless grin, blood dripping from her chin like one of our Louisiana vampiras. My stomach revolts. Even now, two days later, I feel like throwing up.

Dogs start their evening barking and howling in the distance. Don’t know what sets them off unless it’s the spirit of the goat. More dogs join in. The sound moves toward us and sets off still more barking. The barks roll over the village, go up the hill, down the other side and die away. I call it rolling thunder, good title for a book if I ever write one about my experiences in this place. ROLLING THUNDER by David Edmonds. I used to enjoy the rolling barks, even when it woke me at night. But when I think of that miserable little canine that charged out from a haystack and ripped a hole in my leg I want to take a shotgun to every dog I see.

A gourd is passed around. Each of the girls take a sip.

The Machi, sitting on a cushion in front of a drum, begins her lesson:

“Listen to my voice, girls. Are you listening?”

“Yes, Mother Machi.”

“Listen to me and I will speak of days to come. Are you listening?”

“Yes, Mother Machi.”

“Imagine you are a spider in your web. You are there, contented, and then comes another spider. A man spider that you know well. A spider that has danced for you. A spider you knew as a child. A spider who was once the way children are. But now he has changed. He is now a man. He wants what all men want. Do you understand what he wants, my girls?”

“Yes, Mother Machi.””

The dogs start up again. She waits for it to die and continues.

“But he is unfaithful to you. He dances with the other female spiders when you are sleeping. When you complain, he tells you it was a mistake, that it is you he wants and only you. These are the things you want to hear. But he has been unfaithful to you. Should you punish him?”

“Yes, Mother Machi.”

“But how should you punish him? Suppose you have three choices. You can keep him as your mate. You can send him away from your life. Or you can have him for dinner. ”

The girls giggle. The Machi cuts them off with a single beat of the drum.

“At first you cannot decide. Maybe it is the time of the woman’s curse. Maybe it is the effects of the moon or the changing of the flowers, but then one day you realize he is not going to change. He is only showing you the spider he really is, the spider you would have known if you had taken the time to know him. He is not what you hoped for. So what to do?”

In the silence that follows, a little girl in a bright red shawl raises her hand.

“So what should we do, Mother Machi?”

“Eat him!” shouts Puenkel’s daughter.

The Machi kicks her drum and stares so hard at Puenkel’s daughter that the poor girl lowers her head. It grows so quiet I can hear the crackling of the flames.

The Machi speaks again.

“Suppose in your time of sorrow and confusion that another spider comes into your web. He looks better than the first. He is all the things your first spider is not. You like what you have caught. So what do you do with him? Again you have the three choices: you can mate with him, you can let him go or you can eat him for dinner. What would you do?”

“I would set him free,” says the girl in the red shawl.

“And why would you set him free?”

“Because you should be loyal to the first spider.”

“But the first spider has betrayed you,” says another voice.

A discussion ensues. Voices rise and fall. Dogs bark. The gourd is passed around for another sip. After a while, the Machi asks for a show of hands. “Who among you would set him free?”

Hands shoot into the air.

“Who among you would mate with him?”

Other hands are raised.

“Who among you would have him for dinner?”

Puenkel’s daughter is the only one who raises her hand. She also smacks her lips.

The Machi doesn’t seem to like any of the answers. She comes to her feet, brushes herself off and heads to her hut, shaking her head.

“But what is the answer?” the girls cry out.

At the door to her ruca, which is also where Ñashay lives, the Machi turns and stares.

“The answer,” she says, frowning, “is to learn from your mistakes. If you had examined your first choice more carefully, you might have agreed with Puenkel’s daughter and had him for lunch. So the Lesson of Two Loves is to take the time to learn.”

“What does that mean?” says a girl’s voice from the shadows.

“It means you should not hasten to select your first spider.”

She goes in and closes the door. The girls meander slowly away, some of them forming into little groups and continuing their discussion. I head back toward my ruca with Ñashay beside me, and as we trod slowly through the village, passing in and out of dim patches of light from doorway lanterns, she takes my hand.

“What are your thoughts about the lesson?” she asks. “What if you had two loves?”

It’s impossible for me to answer. How can I tell her I have two loves and the Machi’s lesson did nothing to help me resolve it? How can I tell her that my thoughts are with my Icelandic love and Miss Lily of Peru and what a tough choice I’d have if they were both in my life? I can’t. Ñashay is such a darling, such an innocent child of this place, and I’m not going to hurt her.

At the doorway, she wants to come in. I tell her no, that it’s late and I don’t feel well. As she turns to go, a shooting star streaks across the heavens and passes over a volcano that glows in the distance. Ñashay says it’s a sign, but doesn’t say for what.

Maybe it’s a sign that I’ve been too long in this village.

That I should head to Santiago and fight for the hand of my Peruvian love.

Or just go home.

I am so confused.

- Dave with Mapuches

Epilogue 2015

I remained in the village until the end of 1964 and managed to establish a carpenter class with a donation of tools from CARE. My stomach ailment took me back to Santiago, where I shared an apartment with my good friends, Bill Callahan and Mike Middleton. My Peruvian love had gone home to Lima by then, back to her family and boyfriend.

The novel I started in 1964 (Lily of Peru) was published in January of this year by Peace Corps Writers. It’s the story of a RPCV who returns to Peru many years later to take home the woman he’s loved since his Peace Corps days, only to be told she’s thrown in with a bizarre terrorist organization called the Shining Path.

David C. Edmonds is a former US Marine who was a PCV in Chile (1963-65). After the Peace Corps, Edmonds did graduate work at Louisiana State University, Georgetown and George Washington University and earned a PhD in international economics at American University. He subsequently served as a senior Fulbright Professor of Economics (Mexico), university professor and dean (Louisiana, Alabama and Florida), and federal government official in Washington DC, Peru, Nicaragua and Brazil.

He is an author, editor or ghostwriter of eight books and numerous academic publications. His first book, Yankee Autumn in Acadiana received the Literary Award of the Louisiana Library Association and was made into a small theatre production called Les Attakapas. A portion of his second book, Vigilante Committees of the Attakapas, was made into the movie, Belizaire the Cajun, starring Armand Assante. Other non-fiction books include The Guns of Port Hudson (two volumes) and The Conduct of Federal Troops in Louisiana.

His thriller, Lily of Peru, set during the dark days of the Shining Path insurrection, is the recipient of an International Latino Book Award for fiction, the Royal Palm Literary Award (Florida Writers’ Association) and the Silver Award of Readers Favorite. Lily is also a finalist for a Latino-Books-Into-Movies award sponsored by Latino Literacy Now. His second thriller, The Girl in the Glyphs, about a young archaeologist’s search for a “glyph” cave in Nicaragua, also won a Royal Palm Literary Award in the unpublished category.

He currently resides in Florida with his wife Maria.

Beautifully written. Do you have more? I’d love to read whatever you have from your experience there.

Chile 1980-82