BACKYARD RACE HORSE by Janet Del Castillo (Colombia)

Backyard Race Horse

by Janet Del Castillo (Colombia 1964-66)

Prediction Publication

520 pages

April 2013

$40.00 (Paperback)

• • •

Still practicing the Peace Corps

Interviewed by Thomas R. Oldt

Janet Del Castillo (Colombia 1964-66)

Amidst our dreadful political morass, when we can’t even seem to agree on what it means to be an American, the whole notion of idealism is seen by many as naïve if not downright suspect. That is one of the many reasons the youth-led debate over gun violence is encountering such rabid opposition.

But there are large numbers of Americans — nearly a quarter million so far — who have put their idealism to service in a very tangible way, by joining the Peace Corps. Though it has been 57 years since President John F. Kennedy summoned forth the organization as one means of answering his inaugural imperative to “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country,” his call is still being answered today.

Currently there are more than 7,000 volunteers in Peace Corps service in 64 countries. About two-thirds work in heath care and education, the rest devoted to agriculture, economic development and other pursuits.

In 1963, an idealistic young Californian named Janet Del Castillo signed up for service in Colombia. That event, and all that flowed from it, changed her life and eventually led her to Winter Haven, Fl, where for the past several decades Del Castillo, 73, has trained race horses at her lakeside ranch on Eagle Lake.

She is the author of the training manual Backyard Race Horse, a 500-page tome now in its fifth edition, with 25,000 sales to date. Still the idealist — albeit one tempered by hard experience — her mission as a trainer and author is to rid the industry of practices harmful to the animals, especially the use of drugs. Why? “When I saw what was going on I wanted to change the industry in a positive way, just like in the Peace Corps,” she says.

Our conversation, lightly edited for flow, follows:

Like many among us, you’ve taken a circuitous path to your current occupation and place of residence. What was your early life like?

It was a very rich upbringing in many ways. My father was an agent for what is now the Drug Enforcement Administration, working in San Francisco, which is where I mostly grew up. We lived in an old Victorian with speaking tubes. Once my father had to sequester in our house while a trial was in progress, a witness who was going to testify against the mob, making my mother very nervous for a memorable week.

I went to Catholic schools. The nuns encouraged you to help other people, to become a better person. We were a classroom of 52 kids. We sat up straight and kept our mouths shut and stood up when Sister Superior came in the room. In spite of the fact it was very regimented, it did not kill our imaginations.

While attending San Francisco State University I worked part time in the city recreation department, mostly in rough neighborhoods. That turned out to be some pretty good training.

What made you decide to go in the Peace Corps?

I was altruistic … and innocent. It started because I read a book when I was 16 called The Night They Burned the Mountain,” about living in a primitive society, written by a missionary, so the thought of helping people and living in a different culture was the first influence. When I heard about the Peace Corps, to go into a primitive area of the world and save these poor, starving people, that was it for me. I said I’d go anywhere and do anything. I had been working in inner city San Francisco so I thought I had a good background.

President Kennedy inflamed all of us. All my friends were into saving the world. It was that time, we were all so idealistic. So much was going on — registering black voters in the South, civil rights demonstrations, and later blowing up draft offices.

I couldn’t control any of that, but the Peace Corps was a wonderful option. The minute I heard about the Peace Corps, I applied and was accepted into the program on my 19th birthday, Nov. 19, 1963. Three days later Kennedy was killed.

Was the training as regimented as the Catholic schools you had attended?

It was four months at the University of Kansas City. Seven hours of Spanish every day, demonstrations on how to build beds out of sticks, all kinds of practical exercises and skills, a lot of confidence building stuff. Every two weeks there was an evaluation. We were told we were being watched 24 hours a day because we were representatives of the United States, and if anyone we interacted with saw anything they thought was inappropriate, they were to report us.

Every two weeks two or three people would be gone from the original 75. They just tapped them on the shoulder and they were out of there. You could see there were some people who just didn’t belong because if you can’t handle little stresses, you certainly wouldn’t be able to handle the bigger stresses in the country you were assigned to.

Of the original group, 35 got on the plane to South America.

What were your expectations about what you were going to do when you arrived there?

I was in community development and my job was to be a catalyst, to have the community decide what improvements were needed and to help village leaders achieve those goals and improve their situation.

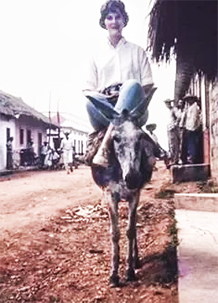

The village I ended up in, a town of about 2,000, had no running water, no electricity and no latrines. On the main street were the “better” houses — board walls, maybe a tin roof. Huts on the surrounding streets were made of sticks with donkey dung, had dirt floors and thatched roofs.

The biggest problem was the death rate. Seven out of 10 babies there died before the age of 7. The attrition rate was terrible, partly because of the environment in which they were born. Parasites and diseases were a huge problem.

A major program was teaching them why they needed latrines and then how to build them. Organic garbage was thrown out on the street where the pigs, goats, chickens and donkeys would snack. Instead of latrines, chamber pots were used and tossed out behind the banana plants. These practices caused much infection and illness. If the villagers would dig the hole, the provincial government five hours away would provide a concrete cover with a hole. That was fine during the dry season, but in the winter when the rains were torrential, the holes would fill up with water and become mosquito traps.

What were your personal living conditions like?

I slept in an old granary where they stored the corn. It had a concrete floor, plank walls and a thatched roof. I’ll never forget the first night, fighting off vicious, blood-sucking mosquitoes and rats the size of small cats that were rustling right above my head with their beady little eyes.

Among other things the experiences there made me understand how wonderful our country was. Clean water and a working sewage system improve the health of any town.

You were there for two years. Did you do good?

Yes, as a matter of fact. It was a challenging experience. It was frustrating. But the little village needed a school and we built one. There’s a hospital there because of me and the doctor I met there who I later married.

I was humbled by the way a large majority of the world lives, with no security, no jobs, few worldly possessions, just getting by day to day. Somehow, in the midst of all that, they could laugh, love and carry on. They had no expectation that anyone owed them anything. They were kind people, generous though they had so little, and I greatly admired their resiliency and ingenuity.

And now, many years and many miles away, you have a very different life raising race horses.

Janet with one of her horses

I’ve been practicing the Peace Corps in my business with the horse industry. I’m trying to change an industry that has many problems — when I first became involved, I didn’t know the extent. I have challenged the status quo since 1992 when I wrote my first book. My goal is to improve the exciting sport of horse racing by suggesting alternative ways of training. You have a choice about how you are going to treat people — and animals. It’s all very simple, it’s black and white — to be good stewards of the land and the animals in our care.

• • •

Thomas R. Oldt is a columnist for The Ledger, and a Winter Haven-based investment professional. Contact him at tom@troldt.com.

Qué gran historia. Janet, si lees esto, me encantaría saber en qué parte de Colombia trabajaste. Las historias de voluntarios colombianos siempre me llaman la atención. Yo soy Tolimense y trabaje cerca de Ibague 1962-63 y lider para Bogota, Cundinamarca,y Meta 1963-64.

G.

What Gary had to say…

What a great story. Janet, if you read this, I would love to know where in Colombia you worked. The stories of Colombian volunteers always catch my attention. I am from Tolimense and worked near Ibague 1962-63 and leader for Bogota, Cundinamarca, and Meta 1963-64.

Jane

t, we were going to travel on horse , you and I! The beauty of the world on a horse! Stay in touch Janet…I am in Panamá wherebI stayed after four Peace Corps assignments…the horses in Paraguay are awesome.

Miss you Janet! Beautiful and colorful Book!

Bob