A Writer Writes — Reflections from a Simpler Time (Philippines)

Reflections from a Simpler Time

By Ted Dieffenbacher (Philippines 1967-69)

The covid-19 pandemic has forced people all over the world to change — to simplify daily living, to isolate themselves from friends, favorite places, and gatherings that had always enriched their lives.

What follows is an odd COVID comparison, about a time when I had to make a dramatic lifestyle change during my time in the Philippines as a Peace Corps Volunteer (PCV) from 1967 to 1969. Single and 22 when I arrived in Santiago, Isabela, I was suddenly challenged to change not only my daily routine but also my way of thinking (and what language to think it in).

Peace Corps gave each PCV a cardboard book locker — a few shelves in a sturdy cardboard box. Each had about 60 books in it, and because no two lockers had an identical selection, I was able every so often to swap books when I met up with other PCVs in the Cagayan Valley.

I am not sure who in the Peace Corps dreamt up the idea of book lockers, but my locker was a lifesaver. I have never read so much in my life. I still have copies of a few favorites, such as Eric Hoffer’s “The Ordeal of Change” and “True Believer,” both of which explain (and predicted almost 70 years ago) our current politics with remarkable accuracy. I had no TV and no telephone. In fact, I remember using a phone only twice in two years, both times calling across town while on short visits to Manila.

I communicated with family and friends back home via slow-motion letters that took about three weeks to arrive. Occasionally, I got a care package from home (I requested Spam, of all things, which I rarely or never ate in the US, and fruit cake at Christmas). Still in touch with my Filipino host family in 2020, I recently learned how a slice of fruit cake back then made them fans forever. Who knew? Luckily (for them) I did not introduce them to Spam.

The Santiago Post Office manager who held my packages for pick-up made it clear (in his indirect and courteous Filipino manner) that the best way for me to speed up delivery (“What’s in this package, sir?”) was for me to share the bounty. He too developed a taste for Spam.

I was faithful in keeping a journal where I sometimes vented my frustration with, among other observations, the “stupid ways of the Filipinos.” I vented most of the frustration messages during the first six months when I was experiencing culture shock most acutely.

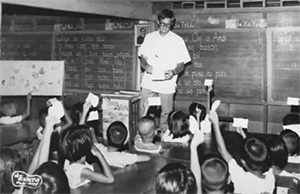

Ted teaching in the Philippines

By the time I left the Philippines after two years, I was torn. Half of me wanted to stay, the other half to go back to the US. I realized that most of what had seemed stupid was not so stupid after all. I started to understand that there was almost always a good reason for certain practices and behavior. Sometimes the reason was obvious, but sometimes it was harder to discern, probably because the behavior began decades or even centuries ago to address conditions that are no longer present in modern life.

I played a table game called sungka (on a wooden board with 16 half-moon cups carved into the board and tiny seashells or stones that are moved strategically from hole to hole). We also played cards. Gin rummy was my favorite. Near the end of my two years, I challenged Jim, another PCV teaching in Santiago — “the first to 10,000 is the winner.” At 200 points per round, we knew it would take many games to get to that number, so we carried a deck of cards with us wherever we went. We played on top of a suitcase in a bumpy bus, in cafes, or wherever there was a flat surface.

As our two years ended, we were running out of time. We headed to Manila for debriefing and our return to the US. Jim was leading in the gin game with 7,000 — well shy of 10,000. As we headed to Hong Kong for a four-day visit, we were determined to fight it to the end. We finished the game, using every idle moment to play. I won. That was a surprise because Jim was a much better card player than me. He continued to the US via Japan. I went the opposite direction, through SE Asia and into Europe.

When I booked my itinerary to the US with a Manila travel agent, I realized that for about $100 more, I could stop almost anywhere. She asked, “Hong Kong?” Sure. “Macao?” Yes, please. “Bangkok?” Yes, please. “Kathmandu?” Yes, please. “Cambodia?” Sure. “Agra and the Taj Mahal?” Yes, please. “New Delhi?” Yes. “Athens?” Yes. “Tel Aviv?” Yes. “Rome?” Yes. “Paris?” Of course. “London?” Yes.

After a one-month blur of airports, hotels, and walk-about tourism in eleven countries, I sat in the dining room of a guest house in London and watched on a black and white TV screen as Neil Armstrong, fellow Ohioan, walked on the moon on July 20, 1969.

When I arrived in New York City, one of the first things I saw was a bombed-out building in Greenwich Village, cordoned off with yellow police tape. Weather Underground radicals had accidentally blown themselves up while making explosives.

That was the beginning of a year or more of reverse culture shock, arguably more difficult than the culture shock I had experienced in the Philippines. Suddenly I was talking about the stupid ways of the Americans, trying to figure out the craziness and contradictions of the 1960s — major progress with a voting rights bill for African Americans, the prospect of real progress for women, and landing men on the moon — alongside the carnage of the Vietnam War and the assassinations of JFK, RFK, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. And then to end the decade, the killing of four students by the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University, 50 miles south of where I was teaching grade 10 English that day, May 4, 1970 —my birthday. That was the final insult for my first year back in the US.

One very unusual destination in my halfway-round-the-world itinerary was Cambodia — in July 1969! I of course knew the war was raging right next door in Vietnam, but young and dumb, off I went. Upon arrival in Siem Reap, I noticed that there were no tourists, not a single one — except me. In the town square, where there would normally be a fountain or statue, there was a US fighter jet riddled with bullet holes. That got my attention right quick!

The next day I wandered alone through the ruins at Angkor Wat and saw only one other Caucasian (a French anthropologist), some water buffalo, and a few Cambodian farmers, bending and stooping as if responding to music as they planted rice in the paddies. No tourists at all. I felt no hostility from any of the Cambodians. In fact, quite the opposite. We did not speak the same language, but they smiled, and I smiled back.

Many years later, I told my lifelong friend Jerry that I had been in Cambodia in July 1969. “That’s impossible,” he insisted, “because I was there in July 1969 — secretly — in the US Army, and there is no way that US tourists were there then.” Only when I dug out my old passport and showed him the visa stamps did he believe me. Now I am curious to know why Cambodia had such a visa agreement with the US while the US Strategic Air Command was secretly bombing eastern Cambodia — and I was walking obliviously through the ruins of Angkor Wat.

My time in the Philippines was full of parties — lots of birthdays, especially for little kids, when everyone was included — aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, friends of the family — and de rigueur — Peace Corps Volunteers.

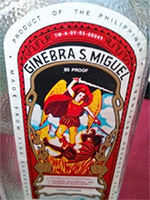

The other type of party was men-only — with some of my Filipino teacher friends and an interesting assortment of others. Featured beverages were San Miguel beer and a ghastly Ginebra, a poor imitation of gin, but with a wonderful label — a colorful image of the Archangel Michael, wielding a sword and slaying a dragon. Sometimes on the morning after, I felt like the dragon.

The other type of party was men-only — with some of my Filipino teacher friends and an interesting assortment of others. Featured beverages were San Miguel beer and a ghastly Ginebra, a poor imitation of gin, but with a wonderful label — a colorful image of the Archangel Michael, wielding a sword and slaying a dragon. Sometimes on the morning after, I felt like the dragon.

Our men-only parties met on average once a month, usually on a Friday night. Each host tried to one-up the others by barbecuing exotic tasties. I ate goat, fruit bat, dog (tastes like beef), cat, and who knows what else (I stopped asking), all washed down by healthy doses of Ginebra with Michael slaying the dragon. One thing Ginebra and Michael did not slay were my “colonic beasties”— that was the tagline of the telegraph sent to me from the Peace Corps doctor in Manila, reporting my lab results.

Other times a group of us PCVs along with Orly, Filemon, and Bien got together to play cards, usually with Voice of America radio playing in the background. The most memorable listen was in 1968, when the radio announcer interrupted the music and said, “Please stand by for a message from the President.” This was highly unusual. We stopped playing cards and fell silent. “What’s he going to say?” we wondered.

Then the deep voice of the broadcaster: “And now, the President of the United States of America.” There was an awkward silence for a few seconds of dead air, and then President Lyndon Johnson shocked the world when he said: “I will not seek nor will I accept the nomination for a second term as president of the United States.” This was arguably the beginning of the end of the Vietnam War, but it took seven more years until American helicopters lifted Embassy staff and loyal Vietnamese off the roof of the US Embassy in Saigon on April 30, 1975.

When not playing cards or sungka, attending parties or doing lesson plans, Cleo, Jim, and I spent many evenings drinking at a local dirt floor café with a jukebox. One of the Filipino regulars loved “Those were the days, my friend, we thought they’d never end” and played it incessantly. Once when he had had too much to drink, he pulled up a chair and inserted himself at our table. Then with Ginebra giving courage, he came out with, “You guys must really be CIA, right?” One of us (Jim, I think) replied, “Yes, we’re here counting strategic carabao” [water buffalo]. Our new friend did not quite know what to make of that.

Some years later during the Marcos era of martial law (1972–1981), I read an article in Newsweek saying that Isabela Province had become a stronghold of the New People’s Army, a militant guerrilla group that organized resistance to President Marcos’ martial law. Who knew? Perhaps our friend in the cafe did, but we PCVs were oblivious.

Another favorite jukebox song was “I Am the Walrus” by the Beatles, with lyrics so strange that Ginebra finally had a useful purpose. Certain songs got played over and over as empty bottles of San Miguel filled the table. Counting empties at the end of the night was the billing system for the pretty Filipina waitress. She was at least half the reason — no, speaking for myself, closer to 80% — of why we hung out at this less than spiffy café.

The bathroom at the café, tucked against the outside wall at the back of the building, was more an outhouse than a bathroom. At night, because there was no light, we had to stumble along, feeling our way against the wall, kicking here and there with braille footsteps until making contact with the cement footpads on the floor above the toilet hole. One night Jim came running out of the outhouse with a stricken look on his normally placid face. He had interrupted a pig.

That style of toilet — footpads above a hole in the floor — was a serious challenge for even the most flexible American. But it was not just in the bathroom that the squat position prevailed. If a group of Filipino men conversed under a shade tree, the most comfortable position for them, apparently, is that squat. Not wanting to be insensitive to their culture, or worse yet, be perceived as lording it over them by standing (they had had enough of that during colonial rule) we tried our best to squat, too, and endured the discomfort, trying not to tip over when our legs went dead. Peace Corps training should have included special physical training to address this!

Cleo, Jim, and I would usually eat dinner at our respective homes, do lesson plans for the next day of teaching, and then go to the café. But suddenly Cleo stopped joining us.

“What? Does he think he’s too good for us?” we wondered. After several months of no Cleo, we learned that he had been courting Corazon in traditional style at her home with parents and the whole family present. And they were engaged to be married! We were shocked, because (a) we could not figure out how they had kept this secret in a town where everyone knew everyone else’s business, especially ours. We did not blend well. Plus, I co-taught with Cora, and she gave no hint of what was going on (b) a “date” usually meant going to a movie with half the family in tow, and (c) we knew that showing the slightest bit of interest in a local girl had better be followed up respectfully. Too many young Filipinas had already been left in tears at dockside at the end of World War II.

The other pressure from some Filipinos, usually strangers at the dirt floor café, was to go “across the river” to the Morning Star “night club.” They relished the idea of seeing how the club managers, patrons, and girls would react to the rare sighting of gringos in a provincial nightclub surrounded by rice paddies.

Having heard incessantly about the Morning Star for two years (usually as a tease from drop-by patrons at the café) we were curious, but cooler heads prevailed. We never did go to the Morning Star during our entire two years — until our last full day, when some of our “friends” insisted. We shared drinks (only) with young Filipinas, and our “friends” were delighted by it all.

I am glad I went, just to satisfy my curiosity, but the lasting memory is sadness. The girls really were just girls, all of them young. Too young. And most were not there of their own free will.

Jim and his host family – 1969

In 2015 while in California, my wife and I visited members of the family that had hosted me for two years in Santiago, including Mrs. Tumanut. Frail at 92 but still spunky as ever, she said just the right thing to Leslie: “Ted was always a good boy.” Phew! Mrs. Tumanut died several months later. I am glad I saw her one last time.

Our Filipino friends and fellow teachers, mostly older women, constantly tried to match us with young Filipinas. They succeeded spectacularly with Cleo and Cora. They married in Santiago and have lived in St. Louis, Missouri for more than 50 years. My wife and I spent a week with them in Hawaii for the 50th anniversary reunion of our Peace Corps group in 2017. It was a wonderful walk back in time with old friends.

Those two years in Santiago were transformative. After that, I knew that whatever else I would do in life, I wanted it to have an international dimension. Having lived and worked as an educator in eight different countries for a total of 27 years since 1969, I have succeeded on that count.

Life in Santiago was simpler, more personal, slower, and in many ways more satisfying. I slowed down and had time to ponder what is important in life.

The 2020 pandemic has slowed me down, too, but not in a good way. I cannot wait until it is safe to travel again, maybe for my third and probably last visit to Santiago.

•

Ted Dieffenbacher (Philippines 1967-69) was born and raised in Ashtabula, Ohio, but has since lived and worked a total of 27 years in Brazil, Costa Rica, Portugal, Thailand, Kenya, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, and Mozambique.

As a Peace Corps Volunteer in the Philippines, he taught English as a Second Language. After Peace Corps, he worked several years as Assistant Director/Counselor of the Boston University Center for English Language and Orientation Programs (CELOP), followed by five years as Director of the Boston University International Student Office.

In American/international schools abroad, he worked variously as English teacher, school principal, and guidance counselor. Academic degrees include BA English/Education, MA International Affairs, and MEd Counseling.

Ted is a member of the South Florida Writers Association, the Cape Cod Writing Center, and the Creative Non-fiction Foundation. He is the author of Lake Effect: Coming of Age in Ashtabula, Ohio, a memoir to be published in 2021. He and his wife, a retired US diplomat, live in Coral Gables/Miami, Florida, and have three adult children.

This is informational travel writing at its best. I learned so much, Ted, and enjoyed the anecdotes as you traveled full-circle: Philippines-home-Cambodia-Philippines. You might have set a record for “most-countries-visited-in-the-course-of-a-month.”

Ted, to answer your question about the book lockers for early PCVs. The idea came from Shriver’s wife, Eunice. She suggested the books. The first locker, I believe, was put together by someone on leave from the military. In 1964 Jack Prebis (Ethiopia 1962-64) went to work at HQ and he put together the next two editions of the book locker. In Ethiopia, I know, many of the first school libraries were started with the books left behind by Volunteers.

A wonderful reminder of past history and though in different countries we were all engaged in many of the same activities. I had forgotten that I learned to play gin rummy and hearts and cribbage in Ethiopia.

Ted—thanks ever so much for writing this narrative. Peace Corps service was a life changing experience for many of us in India, with many similar encounters, including: a) the “resting squat” that men used to relax and talk for hours; b) the many attempts to get us to marry and Indian girl; our misunderstanding of some of the things Indians did that we considered stupid initially but later found to make sense once e understood the setting we were in; d) the value of the book lockers and the time to read all the books. Ours too became the basic texts in local high school library;e) the prelude to a life of international interests and work and so much more.

We were all blessed to come of age in a time when the Peace Corps opportunity became available—let us hope it

continues after the pandemic.

I remember my book locker while I served in the Dominican Republic in 1967-69. I read almost all of the books and also traded with other Volunteers. I can’t remember what I did with it when I was preparing to leave, I believe I gave it to another Volunteer.

While there were more ‘regular’ outhouses in the DR with bench seats, mine was in need of repair. When I arrived at my final home for two years, the landlord had been intending to build a new outhouse and the hole had been started in the yard but never completed. The old outhouse was full of empty five gallon peanut oil cans, which I had to have hauled away. There was no roof and it was made of ‘posts’ tied together with rope so there was space between the posts. After a good cleaning, I used the outhouse for two years, often wearing my rain slicker when necessary, and keeping my paper under a coffee can to stay dry. The intention of my Dominican boss and me was to build a new one but between our work on other projects, that never happened. When I left the house, the outhouse was still there. On a trip back to visit friends after about 15 years, I noted that the house had been replaced with a newer home and another bathroom facility.

By late 1968 when I arrived in Colombia, we had only remnants of old book lockers but I remember them fondly — especially Quiet Flows the Don and James Michener’s Iberia which left me with an insatiable desire to explore Spain. For obvious reasons, I too never visited those ‘specia’l nightclubs and houses. In Colombia they were called La Casa Blanca (the White House) and it seemed there was one in every neighborhood. Our musical backdrops were similar. For our training group in Escondido, California (in a former nudist colony, now a Buddhist retreat), Those Were The Days my Friend was a staple, but the highlight for our group was crawling in through the windows of the locked training room to watch the Beatles on Ed Sullivan. It strikes me how similar PCV experiences are despite time and distance. I am also still in contact with my trainee host family and my family in Barranquilla. We too were accused of being CIA, reverse culture shock was unquestionably more difficult coming home, and the experience was definitely life changing/enriching. Thanks for awakening old memories.

Yes, book lockers were the best ideas ever! In our little village of Shivalli in what was then Mysore State – now Karnataka – in southern India, Peter, Diana and I used them for our amusement, continuing education and in helping many young village Indians gain a wider world perspective. I don’t know how volunteers got along without them after the idea was foolishly scrapped in later years.

We also can identify with the squatting syndrome and, while uncomfortable at first, we not only grew accustomed to squatting over hand flush latrines but also established a small business manufacturing them for sale to the local municipal government for use at railheads during “sante” days when farmers from all over the district would bring their produce to sell at the huge outdoor monthly markets.

Our handmade platforms and bowls were relatively light weight and yet quite strong as they were at first reinforced with iron rods. When rods became unavailable we substituted strips of bamboo with holes drilled in each end and nails or screws inserted. It worked just as well and made manufacturing cheaper. We trained several locals and when we left after our two years that small local industry was providing a bit of extra income for them.

Our 65 to 67 Peace Corp group still gets together to meet every few years although with each year our numbers decline. This year’s reunion had to be postponed due to Covid but we’re hopeful 2021 will get us back together somewhere pleasant.

Stay tuned!

Ted, thanks for bringing up fond memories of the Peace Corps. Peace Corps service was certainly life changing event for me. I first introduced to the Peace Corps program by a RPCV from Indonesia in 1966. As a farm boy from South Dakota this sounded like a good way to get off the farm and experience something really different. So I applied and was accepted for teaching in Nigeria, but the civil war ended that potential assingment. I was then placed as a teacher in Tanzania and went into training. At the end of the training period there was a disagreement between the US Government and Tanzania. Our program, Tanzania 13, was cancelled. Volunteers were placed in several East African countries.as teachers. Because I had a background in agriculture I was sent to Kenya and was told to go to the Ministry of Agriculture and find an assignment. I was given the names of a few Office Directors. One was the Director of Animal Research for a posible position at the National Swine Research Station. I was waiting outside his office when another agricultural director came up to me as asked if I was the PCV looking for a job. He asked if I knew anything about wheat framing. I told him I grew up on a wheat farm and I knew how to operate all the farm equipment for grain farming. He opened the door of the Research Director’s office and said he needed me to work on large-scale wheat farming. Next day I was taken to the government motor pool as assigned new Land Rover. Then off to the camping equipment store for tents, cots and other camping gear. I was told that I would be living in a tent with a tractor ploughing and planting unit. It was in the Mara Game Reserve. After two years, and 5,000 acres of wheat, I extended and was assigned as the first PCV to the Lamu Island in the India Ocean. The book locker and a short-wave radio kept me informed. and entertained. My way back to USA was via a boat from Kenya to India with an old landrover on board. Then came a three month road trip from Bombay to London. I had a graduate assistanceship to Ohio University, and Ted and I met as we both worked in the residence halls. After OU I returned to work in Keny in agribusiness management. Eventually joining USAID in 1987. Like Ted, I worked in several countires until my full retirement in 2017. Never had a job in the USA. I will enjoy Ted’s Zoom on Sunday. Peace Corps was my start for the most wonderful experience of a life time.

Greg–I love what you wrote. I knew you had been in Kenya, but not about wheat farming and then Lamu. I’m sorry for not following up with you lately, but with Covid etc., I’ve been grounded a bit. But would love to spend time over some beer next time we get to the gulf side of Florida. TED