A Writer Writes: “Hemingway in Africa” by Geri Critchley (Senegal)

Hemingway in Africa

•

By Geri Critchley (Senegal 1971-72)

WHEN I EMBARKED on my travels to Africa, I had no intention of encountering Ernest Hemingway. However, while trying to get money out of a non-functioning ATM in Moshi, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania, I met a travel agent who offered to somehow use his agency as an ATM so I could pay a Mt Kilimanjaro guide.

In the middle of the transaction, abruptly changing focus, he told me that he had attended St Ursula’s boarding school nearby in Moshi Village with Ernest Hemingway’s granddaughter Edwina, daughter of Hemingway’s son Patrick. He continued to tell me he is still in touch with Edwina who used to live in Florida but moved to Montana and that she has the rights to Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea.

Of course he now had my attention; I told him I was interested in learning more. He must have been surprised that someone was interested in Hemingway so he continued to tell me that he could find me a taxi driver who knows the outskirts of Moshi to bring me to the house where Hemingway stayed when he visited his granddaughter. Then he abruptly stood up from behind his desk to find an experienced taxi driver who would be able to find this house.

After giving many instructions and a map to the driver, the travel agent sent me off.

We drove 20 minutes out of the city of Moshi to a small unmarked dirt road at the end of which was this dilapidated house that had not been lived in for decades. Hemingway stayed here while visiting his granddaughter since St Ursula’s boarding school was nearby. (We also drove by the extensive Kibo coffee plantation that provides Starbucks with some of its coffee the driver told me.)

I can only surmise that some of Hemingway’s inspiration in writing The Snows of Kilimanjaro came while staying at this house visiting his granddaughter and of course while a ranger at MT Kilimanjaro.

I don’t know if many others know this connection to Hemingway since his adventures in Africa are not evident to the tourists. There was no mention of Hemingway when I was at MT Kilimanjaro, yet I have since discovered that Ernest Hemingway was a volunteer ranger in 1953 for at least six weeks at the Masai Game Preserve at the foot of MT Kilimanjaro – less than an hour away.

Ernest Hemingway’s second son, Patrick Hemingway (born 1928) is the first born to Hemingway’s second wife Pauline Pfeiffer. During his childhood, Patrick travelled frequently with his parents, and shortly after graduating from Harvard University in 1950, he and his wife Henrietta moved to East Africa where he lived for 25 years.

From late 1953 to early 1954, Ernest and his fourth wife Mary set out on a year plus adventure that included a long East Africa expedition, in part to visit his son Patrick and his wife. Ernest also felt he had lived too long at sea level and “wanted higher ground” once more, and Patrick lived 6,000 feet above sea level in the African highlands at Johns Crossing, Tanganyika.

Ernest wanted to relive his 1930s African experience and get back to this hill country of Africa where he had known what he called “pursuit AS happiness”. This pursuit brought more pain than happiness towards the end of his trip when Ernest Hemingway went in a small Cessna 180 plane to sightsee in the National Parks with his wife during which he was in two successive plane crashes and was actually reported dead. He sustained a severe head wound – untreated until he left Africa. He broke open his crashed plane’s window with his head when the doors wouldn’t open which may have been a factor in his depression in his last years before he committed suicide in 1961. Risk and adventure seemed to trump all other interests in his life (except writing).

Patrick Hemingway lived for much of his life in Tanganyika. Before moving to Africa, Patrick studied agriculture at his mother’s (Pauline Pfeiffer, Ernest’s second wife) plantation in Piggott, Arkansas. Patrick used his inheritance after her death to buy a 2,300-acre farm near Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. His life in East Africa was incredibly interesting. He ran a safari expedition company; served as a white hunter/professional big game hunter to wealthy patrons and as an honorary game warden in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. He started a safari business, Tanganyika Safari Business, near Mt. Kilimanjaro in 1955, Patrick ran it for over a decade. He gave it up in the early 1960s when his wife was ill.

In the 1960s, Patrick was appointed by the United Nations to the Wildlife Management College in Tanzania as a teacher of conservation and wildlife in Arusha which is near MT Kilimanjaro and Moshi, Tanzania. (I was told that Patrick started an environmental school nearby, but I do not know if it is true.)

After Ernest Hemingway’s eventful expedition to East Africa in the 1950s, he decided to pull together his recollections into a book like he had 20 years earlier when he returned from Africa and wrote Green Hills of Africa. He worked sporadically upon his return to Cuba in the early 1950s recollecting his adventure into a book which is a blend of fact and fiction: True at First Light. He never finished it. Patrick edited his father’s book and finally published it in 1999. The manuscript was in the John F. Kennedy Library Hemingway Archives, and Patrick edited the 800 pages down to half the size. Patrick had been present with his father during much of the expedition and was familiar with the events of Africa during that year which he describes in the “Foreword” to True at First Light. Patrick also visited his father often in Cuba and no doubt recollected with him about his African adventures.

Patrick Hemingway’s father Ernest died in 1961, and Patrick’s wife Henrietta died in 1963. When Patrick left Africa, he moved to Bozeman, Montana where he has lived since 1975. He oversees the management of Ernest Hemingway’s intellectual property, which includes projects in publishing, electronic media, and movies in the United States and worldwide.

When asked by George Plimpton about the function of his art, Ernest Hemingway said in his signature “one true sentence”: “From things that have happened and from things as they exist and from all things that you know and all those you cannot know, you make something through your invention that is not a representation but a whole new thing truer than anything true and alive, and you make it alive, and if you make it well enough, you give it immortality.”

Ernest Hemingway has certainly touched immortality….. and more.

•

Dan Wemhoff, Colombia (1961-63) researched some of this background. Dan met Patrick Hemingway years ago.

Geri Critchley’s (Senegal 1971-72) thirty-plus-years career has included managing and supporting global and domestic NGOs in

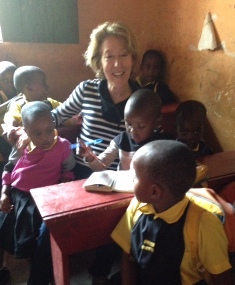

Geri teaching at Best Hope Pre-School

partnership with many organizations including directing The Experiment in International Living (World Learning) in Washington, D.C. and Canada, organizing the Harris Wofford World Learning Global Service award event, and assisting with Special Olympics World Games, among many other NGO connectons.

She just spent several months teaching at Best Hope Pre-School in Moshi, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania, teaching conversational ESL at a Women’s Center: Feminin Pluriel in Rabat, Morocco, visiting NGOs in Nairobi, the Nyumbani AIDS orphanage, and the Director of the Africa Peace Service, as well as seeing friends in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Her website is: http://www.linkedin.com/in/gericritchley

Fascinating anecdotes and insights. The quote about the function of fiction by Hemingway is a gem. Thank you Geri (and Dan).

Geri,

Good piece and so good to hear from and about you again. Lord, you also did put some good miles behind you recently!

Tom

Hi Geri,

Your article helped me solve a 65-year-old mystery. Who was Mrs. Hemingway – my first-grade teacher at the Aga Khan Indian School, Arusha, Tanganyika at around 1957? Schools were legally segregated during the British colonial rule. For reasons that were not clear to me during that time, I was enrolled in this school. The African school I was hoping to attend was across the street from our house. Instead, I had to walk about 2 km to this school twice a day. When I met her, I was an angry, confused, and sad little boy. To make matters worse, I was the only kid who couldn’t speak English. The Indian kids had a headstart in kindergarten. Although I never spoke directly to her, I could tell she really cared about me. Mrs. Hemingway is the best teacher I ever had.

I have been looking for her on and off since I moved to the U.S. in the mid-70s. My search was always focused on Ernest Hemingway’s wives, but their timelines didn’t fit mine. However, after reading your article I started to focus on Patrick’s timeline and story. Last week, I spoke to him by phone and he confirmed that my teacher was his late wife, Henrietta Broyles Hemingway. He was also able to recall that she took a teaching position at the Aga Khan school to keep herself busy while he worked as a Hunter and a Guide. I can’t wait for the Pandemic to be over so that I can meet him in person. I would like to connect with his daughter, Edwina so that I can share my story with her. Mrs. Hemigway will always be my “guardian angel”.

By the way, our school (Arusha Secondary) was one of the first to accept Peace Corps teachers during the mid-60s. Thanks for helping me.

Geri,

I was in the Peace Corps posted in Moshi 1966-67 and had a connection to Patrick Hemingway on the south side of the mountain (Moshi) and to the father on the north side of the mountain (Loitokitok, Kenya) where I worked at the Outward Bound Mountain School my second year.

Living in Moshi and being very interested in the outdoors, I climbed the mountain frequently from various routes then available. One was the Mweka Route which the African Wildlife Management College pioneered for their students. Patrick was teaching there at the time. He specialized in counting herds from the air in the Cessna that he piloted. Anyway on an Easter weekend in 1967 I organized a small party of climbers to ascend via the Mweka Route. I went through the college to let them know my plans, and they asked if I would allow a couple of their visitors to join my party. One was a German doctor. On the third morning of the climb when we were about to go to the summit, the German doctor slipped out of camp early and went ahead on his own. He never said a word to us.

On our way up we did not see him either going up or coming down, so we assumed correctly that he had gotten lost on the sparsely marked trail coming back from the summit. After not finding him at our base camp and seeing his gear still there, I decided to run down off the mountain to get a search party started from the school. After my alerting them, the school sent a party of 10 or 15 people including their fittest students and instructors up there. A day later no word had come down, and the doctor had not shown up. Some communication was needed with the searchers to let them know to keep looking. It was two days walk to get to where they were looking. So the powers that be asked Patrick to fly his Cessna up to where the search was going on and drop a message to them to continue looking. I was asked if I wanted to go along for the plane ride, help navigate, and drop the message tied to a rock. There was one other passenger, a young American whom I did not know. In a Cessna you don’t just take off from the airport located at 3000 feet and fly a straight line up to the location at about12,000-14,000 feet. The little plane had to fly in a corkscrew gradually climbing up and up until it reached the proper altitude, then bank toward the mountain and fly to approximately where we thought the searchers might be. In retrospect I think this was a very dangerous mission for a lone bush pilot in a Cessna. Anyway as we approached the ridge that was our target, we banked again and flew across the land at about 13,000 feet but only a hundred or so feet above the ground. A sudden downdraft could easily have put us into crash mode. Fortunately on the first pass we saw some of the search party and doubled back and dropped the message, then headed back to the lower altitude at the Moshi airport. So that was my contact with Patrick. I’m sure he remembers that flight although certainly not me. He may have been acquainted with the other fellow in the plane. The searchers never found the German, but fortunately for him he did find his way down the mountain, taking some very misguided ways in the valleys rather than staying on the ridgelines. In the valleys one often runs into waterfalls and cliffs that you have to climb back up and around to continue on your way down. The German was pretty torn up by thorns and he had lost most of his toe nails, but he survived.

That was not my only Hemingway story from those days. One of the staff at the Wildlife College was Frank Poppleton, a local fellow raised in Kenya. I knew him from playing rugby in Moshi. He was about ten years older than me but still a very fit fellow. Ex military as well. I found his obituary a few years ago and learned that he was the guy who led the search team that rescued Hemingway in one of his plane crashes in Uganda. You can find this by googling ‘Frank Poppleton’. The story is on the obit.

When I moved around the mountain to work in Loitokitok, Kenya, I had a third Hemingway contact. An old Masai had gone a bit western and owned a Land Rover and had a small garden business supplying vegetables to our school and some other customers in this very isolated community. His name was Norman Kipari. He was very personable fellow and we developed a friendship over a few months time. He took me to a circumcison ceremony one weekend which to me was quite an honor. . We talked quite a bit, and he brought his children to see me one day. He even tried to be a matchmaker with me and another Peace Corps girl. Long story for another time. I asked their names, and he told me they were Ernest and Mary. I knew that Hemingway had hunted in that area near the Kimana swamp in the 1950s. So I asked Norman how he selected those names for his children. He told me that as a younger fellow, speaking some English he was able to get employment with the safari company that took Hemingway and his wife Mary out into the bush for hunting. For some reason Mary took a liking to Norman and corresponded with him and helped set him up in the farm business. In gratitude Norman named his two children after the couple. This is most unusual for Masai to do anything but herd cattle in those days. A few worked at our school, but they were the minority.

So those are my three contacts to the Hemingway legend.

Hi George,

Mea culpa, i just opened up and reading your message for the first time

Amazing stories!!

Thank you for writing them up and sending them.

Patrick Hemingway would love to hear these stories and also the JFK library.

I would love to talk with you after I move

to Palo Alto, CA mid May.

Look forward… stay healthy!

Geri geri.critchley@gmail.com

202-378-6416

My Grandfather George Roca was friends with Patrick.

He had a farm in Tansania at the time Patrick lived there and they became friends.

My Grandfather was unfortunately killed in Northen Tansania. My grandmother then moved back to Barcelona and on each visit I made to her, she would take out Hemingway books and show me these wonderful books she had taken back with her signed by Ernest himself. Unfortunately she fave away all her possessions to collectors in Barcelona and none of these treasures stayed in the family.

It’s been marvellous reading up on Patrick’s past.

Thank you