RPCV Sculptor | Joel Shapiro (India)

How Joel Shapiro ‘Retains the Intimacy’ of His Staggeringly Large Sculptures

Ahead of a solo exhibition at New York’s Pace Gallery, we step inside the studio of the seasoned sculptor.

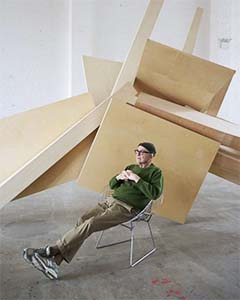

Joel Shapiro in his Long Island City, New York studio, 2024. Photo: Kyle Knodell, courtesy Pace Gallery.

by Tim Brinkhof — August 27, 2024

Share This Article

Ever since he participated in the 1969 “Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials” exhibition at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, Joel Shapiro has been a fixture in the world of modern American sculpture.

The 82-year-old artist traces the genesis of his career to his experience serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in India 1964 to 1966. There, in between teaching villagers to dig latrines and build smokeless ovens, he became enamored with Indian sculpture, which introduced him to the medium’s psychological dimension. “India,” he later said, “gave me a sense of… the possibility of being an artist.”

Born in Queens, New York, in 1941, Shapiro studied at New York University, earning his B.A. in 1964 and his M.A. in 1969, the same year “Anti-Illusion” launched. Over the next 50 years, his work, always abstract and geometric, sometimes vaguely humanoid, experimented with the inherent tension between gravity and structure. Meant to be seen from a variety of angles, his sculptures inspire the viewer to reflect on their own physical and psychological relationship with space.

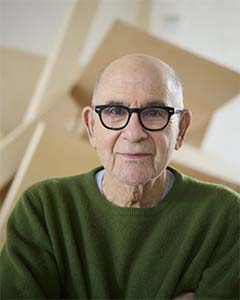

Joel Shapiro in his Long Island City, New York studio, 2024. Photo: Kyle Knodell, courtesy Pace Gallery.

This is precisely what visitors can expect from his upcoming solo exhibition at New York’s Pace Gallery, which will be accompanied by a catalogue featuring an essay from the renowned poet and author Vincent Katz. Shapiro’s first appearance at Pace since 2014, the show includes ambitious new sculptures such as the show’s centerpiece, ARK, a towering conglomeration of wooden boards and beams that just barely appears to hold itself together.

“I was just painting it,” said the artist in a Zoom conversation from his studio in Long Island City, Queens. It’s a large studio, and for good reason, too. Just as visitors at the Pace exhibition will have to walk around his sculptures to fully appreciate them, so does Shapiro require a space where he can inspect his unfinished creations from every angle, even when they’re 12 feet tall.

Tell us about your studio. How does it compare to others you’ve had?

It’s big. There’s the ground floor, which is about 90 by 70 feet, a second and third floor which are about the same size, and a little roof section we call the penthouse, even though it’s not actually a penthouse. I tend to do smaller work upstairs and larger work downstairs, where we have 22 foot ceilings. It’s got wonderful light, too.

How do you feel the layout of your studio reflects your ideas, tastes, and creative process? For example, do you work better when things are messy or organized?

When I’m working, it gets pretty messy around here. Especially on the third floor, where I’m conceiving and putting things together before bringing them downstairs. The downstairs is highly organized, and that’s because my studio assistant is very disciplined, unlike myself. I tend to pick up stuff lying around me when I’m working, using it for my sculptures. Only when things get too chaotic will I make an effort to organize things.

Shapiro’s studio in Long Island City, New York, 2024. Photo: Kyle Knodell, courtesy Pace Gallery.

The space in which you create art puts limitations on what you can do. The studio I have now is so big that, at one point, I began to suspend pieces from the ceiling, supported from three and four points, adjusting and moving them. In this case, the studio allowed those things to happen.

Does your studio put you in a particular headspace that helps you create art?

What you’re looking for when you work is a little moment of rapture. I’m not so sure if that’s conditioned by the studio, but the critical thing is that if you’re on the brink of having such a moment, it’s not suppressed by the space. That said, I’ve worked in all kinds of space, for example inside abandoned buildings from the ’70s. But while space influences the work, I think the inspiration of the artist is ultimately more important.

Do you have any pieces that you decided to keep for yourself?

I have kept lots of pieces over the years. I’m 82 years old, and will be 83 at the end of September, plus my wife is a painter, so together we have a lot of work. Actually, we have a warehouse located next door to the studio, a 7,500-foot warehouse with two basements filled with prototypes and other things.

Shapiro’s studio in Long Island City, New York, 2024. Photo: Kyle Knodell, courtesy Pace Gallery.

It’s an active space. Almost everything is in crates, so we haven’t done anything with it. The warehouse does have a back portion that’s actually finished and one could exhibit work there, but I haven’t done that. I haven’t had time. New work is always so prescient that it doesn’t allow me to do too much with the past. Curating the past—that’s someone else’s job.

Does the space in which a work of art is created and exhibited influence its meaning?

If the work is strong, it should still convey your intent regardless of the space around it, though a miserable space can certainly compromise a work. You always have to be conscious when you’re installing your work in a public space or gallery space, and pick a point of view that helps people experience the work.

Sometimes I’m working on a small piece at the studio that I like, but then I move it and suddenly it doesn’t look so good anymore. The point of view of the receiver is totally critical.

Can you tell me about ARK? What was the most challenging aspect of working on that sculpture?

ARK was a piece I made maybe two to three years ago. I conceived of the work in late 2020, early 2021, and built it this year, but larger. I was grabbing pieces of wood lying around me, sawing them off and putting them together rapidly with pin guns, which I use because they allow me to join things together fast, though they don’t make for a sound structure.

After looking at smaller versions of ARK for years, I decided to build it 12 feet tall. The most complicated aspect of translating a work into that size is retaining the intimacy. We built it out of spruce lumber and aircraft plywood, a process that took between six and seven months. I had lots of doubt. Every artist has doubt, I don’t care what they say. They have moments of exhilaration, moments of doubt.

Joel Shapiro, ARK ( unfinished), 2020/2023-2024. © Joel Shapiro. Photo: Kyle Knodel, courtesy Pace Gallery.

We made all the components separately. Actually, each component could be an individual sculpture. I kept thinking the combination wouldn’t be as interesting as the individual components, that the sum of the parts wouldn’t be greater than the parts themselves. But as I began to join them together, I realized that was not the case. And when the piece was all assembled without paint, it was really exciting, more exciting.

Shapiro’s studio in Long Island City, New York, 2024. Photo: Kyle Knodell, courtesy Pace Gallery.

It was a whole different experience, which isn’t always the case. Frequently, making things larger results in dumbing them down, as is the case with a lot of public sculpture.

When you feel stuck while working, what do you do to get unstuck?

If I’m stuck in a situation, I start doing something else, which probably is a way of investigating why you’re stuck. When you’re stuck, it may be not understanding what you’ve done or are doing. I am never working on a single piece. ARK is the third sculpture I’ve painted recently. I was stuck on color. Ultimately, I settled on the same color as the original model.

What tool or art supply do you enjoy working with the most, and why?

I like wood and I like pin guns. Pin guns are a little hairy, though. You have to watch what you’re doing. You’re basically shooting. It’s a gun, so you have to watch your hands. As for wood—it’s not that I like wood, but I find it easy to work with, with saws, sandpaper, power tools. You can glue it, pin gun it. Pin guns let you join something asymmetrically to something else, giving it a degree of wobbly support.

“Joel Shapiro” will be on view at Pace, 510 West 25th Street, from September 13 to October 26.

Wonderful piece. I wish there had been a bit more about how he finally gets all of the pieces to adhere and make the sculpture stable. It is also amazing to see how Peace Corps volunteers have been influenced so differently by the places where they served.

The Government of India, under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, made a request in 1963 for Peace Corps Volunteers to assist with establishing, among other things, a poultry industry that would address the need for nutrition in the population’s diet plus provide income to its farmers. By 1975 that request turned into a reality that made India the home of the 3rd largest poultry industry in the world. This co-operative enterprise has been well documented by the Peace Corps in Washington and serves to illustrate the power of PCVs in action.