Thelma Firestone’s Daughter by William Siegel (Ethiopia 1962-64)

Will Siegel went to Greenwich Village after his Peace Corps (Ethiopia 1962-64) tour, playing in and hung out at the clubs made famous by Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, and now dramatized in this new movie featuring a character named Llewyn Davis.

In his time in the village, Will performed as “Will Street” at Gerde’s Folk City and The Bitter End, among other village clubs, and he knew, and hung out with, the Roaches, George Gerdes, Loudan Wainewright, Steve Goodman, and all the young artists who came through New York searching for fame and fortune, or at least a way of life.

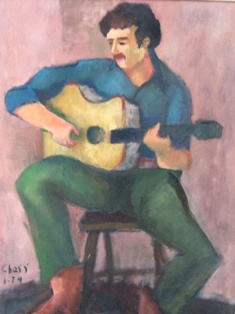

Portrait of Guitarist Will Street (Will Siegel) by Artist George Cherr, 1974

As he wrote me recently, “I lived on University Place and hung out at The Kettle of Fish.” Most of these places (and people) are in this new movie about that time in Greenwich Village when everyone loved folk music.

After New York, Will moved to LA, where he worked on a TV show and then to Boston to pick up a masters in creative writing at Boston University. It was during those years that he wrote a series of stories about his time as a folk singer guitarist in Greenwich Village. Here is one of those stories.]

•

Thelma Firestone’s Daughter

by Will Siegel

She ambles into the club on a Saturday night with four or five friends and catches my attention right away. The group makes a noisy entrance, squeezing past people in the second row of tables, taking no notice while I try to entertain the patrons. I thump my guitar and watch her sit down. She looks me over as if she means to place me from her past. The group must have stumbled into Folk City to get out of the cold and catch a glimpse of Village nightlife before heading uptown. When I realize they’re not paying attention, I go over to the side of the small stage and pick up my twelve-string, which allows me to pretend I have a back-up band. “You heard of the Tennessee Waltz,” I tell the audience, looking away from these stumblebums. I worry too much about what people think, but I can’t help it. “I’m going to play you the West Virginia Rock,” I say. I start in running my fingers up and down the neck of the guitar pounding with my right hand across the strings, making as loud a racket as I can on that big twelve-string acoustic. It’s not a band or anything, but it’s my only dance tune. I can clang out quite a commotion with my ratchety voice turned up a notch:

Going once, going twice,

Up in the holler drinking from the crock,

You gotta get loose

Doin’ the West Virginia Rock.

It’s a song I wrote after Big Eddie, a manager-producer, who I know from the club scene, listened to several of my backyard ballads and protest songs with weary inattention.

“Gimme something I can dance to,” he said sharply.

“Never worry,” I shrugged. What the hell, I thought. That night a few lines and a chorus jumped out from the back of my head. I wrote the song in half an hour and took it up to Big Eddie. He showed it around, or so he said – but never found anyone to cover it. I use the tune now to wake the audience, or on hopeful nights, catch their attention. I shout out the lyrics, but these up-towners turn up their talking and laughing.

Hey, I’m used to the noise; it’s part of the club scene and I usually let it go, except that this time I try harder than usual, maybe because she’s still studying me. I finish my set as they’re being served. I come upstairs from stashing my instruments during Mad Otto’s second number just as the whole noisy troop leaves. Looking after her, the neon from the flashing light outside the club stings my eyes.

The next night she comes in alone. I’m sitting at the back just before my set with my fingers wrapped around a beer. She walks right over and asks if she can sit down. She radiates the scent of society, or at least the caste of money. I’m amazed that such a choice woman would circle back to meet some no-account folk singer.

“Sure,” I say.

“I saw you last night,” she says, unzipping a green parka. She’s wearing a thin dark sweater, jeans and smart cowboy boots. “Did you make those songs up?”

“Was that you and your friends giving me the competition?” I ask. I would have pushed my hat back if I’d been wearing a hat.

“I’m sorry,” she says. “We didn’t mean to disturb your music.”

“Oh, that’s all right,” I say. “Music in this place is wallpaper. People come to look at each other and drink beer. I keep telling Mike to put in a player piano.”

“I can’t decide if you belong here,” she says with a laugh. “I don’t believe I heard any Cole Porter last night, did I,” she adds. Her face flushes. She has a small, quick smile, a bit girlish and at the same time, practiced like a model. She tilts her head, and gives me some kind of look like where have you been. I sip my beer to get through the moment.

“Do you play here all the time?” she asks.

“Once in awhile I convince Mike to let me play. He claims business goes down 50% the week I’m here, but he’s kind of sentimental.”

“I thought you were pretty good for not being Cole Porter.”

“Really?” I say. “Is he a folk singer I might know, or do you mean coal tender?”

“We have to get you above 14th Street,” she says. “Maybe Vegas. It’s over west of New Jersey.” She pronounces the word “Vegas” like someone who’s been there.

“I don’t know if I’d like Las Vegas,” I say. “Is that where this Cole Porter works? Any relation to Old King Cole?” I add.

“I’ll bet you’re just fine in New York,” she says.

“So, what’s your name?” I ask.

“Nikki,” she says. She flashes a larger smile, though this one seems less genuine.

“Nikki,” I repeat. “As in Nicky the Greek?”

“Nikki,” she says. “As in Elizabeth.”

“Oh, that Nikki,” I say

“From the billboard outside, you’re Mad Otto, Jimmy ‘Blues Boy’ Smith, or Floyd what’s-his-name.” she says.

“And who would you go with?” I ask, glancing at her fancy Spanish boots.

“I could go along with Mad Otto, but you might be the Blues Boy. I don’t know. You seem too happy to be singing the blues. You don’t seem like a Floyd, either.” She looks at me directly.

“Floyd’s not my real name.” Right away, I get a queasy feeling in my stomach. Just fooling around, I figure I’ve already told her too much. I better back off. Then, I think – Never worry, man, it’s a chick in a bar in New York City, where you rarely see the same person twice.

“What’s your real name?” she asks, uncrossing her legs and softening her look.

“Now that would defeat the purpose of changing it, wouldn’t it?” I say.

“My mother uses a stage name,” she says. “I’ll tell you her name, if you tell me yours.”

“Mine’s not a stage name. I’m on the run,” I say. “Already on the dark road.” I try to add a note of mystery.

“Oh,” she says, turning serious.

I’m disappointed that Nikki isn’t willing to continue the banter. I’m most comfortable, especially with women, when I’m joking. I sense a lessening of her intensity.

“Want a beer?” I say. “Or a Tom Collins? Rob Roy’s real name, by the way.” I’m wondering if there’s some desperation in my voice, trying to bring the conversation back to an even keel. I don’t feel even. In fact, I feel desperate to get her attention back. I could almost see her looking down on me – like I wasn’t quite who she thought I might be and maybe she made a mistake to come all the way downtown for some lame conversation.

“No thanks,” she says, looking away. A tired look comes into her eyes, the muscles around her mouth tense.

I’m trying to think of another game to hold her, but I’m paralyzed by my own lack of importance.

“I’ve got to go,” she says. “Want to get together sometime and do something?”

“How can I resist?” I say.

“Give me your number and I’ll call you.” She takes a pen and paper from her purse. While I write down my number she puts on her parka. I hand her the paper. She waits until I return the pen.

“OK, Floyd or whoever,” she says. “I’ll give you a call.”

I watch Nikki walk out the door. It’s the first time I’ve ever been asked out by a woman. I feel as though she robbed me of a vague something, but I’m excited. She won’t call, I tell myself. A lot of crazy women troop through the Village. I have to get ready for my set, so I try to think about other things, but I remember the way she said Vegas and advised me to stay in New York, like she knew what she was talking about. I have better things to think about. An opportunity’s coming my way – could make a big difference in my life, but as I go downstairs to tune my guitar, I can’t get her out of my mind.

Nikki calls me the following Friday.

“Is Floyd or whoever, there?” she asks.

“This is Floyd,” I say. “Whoever is out.”

“Want to get together tonight?” she asks.

“OK.”

“What’s your address? I’ll come by about seven. We can decide what to do when I get there. Is that OK?”

“Sure,” I say, and tell her my address. “Don’t you want to have some polite chit-chat on the phone, seeing as we just met?”

“See you at seven.” Click.

I toss the phone handle in the air, snatch it smartly and place it in on the cradle.

I realize I would have preferred to meet her at the coffee shop on the corner, but couldn’t get the words out. I’m not thrilled with my place. It’s kind of an artist garret that’s become small and run down while I wait for my ship to come in.

Never worry, I think, and then I think – I’m always worried. You know, it takes a worried man to sing a worried song. Why am I in this racket, anyhow? What’s the use? I couldn’t even muster up the words to tell her I prefer to meet at the corner coffee shop and I’m powerless to get my own way.

She shows up about seven and doesn’t even look the place over. She’s wearing the same parka and jeans. She puts her arms over my shoulders, looks up into my face with a glamorous gaze, and kisses me. At first I’m uncomfortable. I think maybe she’s going to suddenly push me away. Then, we get into the kissing. I’m into the moment and the worry goes.

We never even make it to the bedroom. By the time she has my shirt off we’re lying on top of her parka, struggling with arms and legs. I had a buddy back home in West Virginia who would’ve called it zero to sixty in less than ten seconds and then added some sound effects. We only take a break when I can’t get her bra off. She sits up and takes it off for me with a look that says, roughly, “You should have learned to do this in high school.” We get right back into it. She has a voluptuous body that purrs as I move my fingers along her skin. She urges me on, but at times I feel useless as if she’s guiding me down her own highway; it doesn’t matter if I want to go, just that she needs me to get there. Truthfully, I don’t care, because the joyous ride and the way it’s happening strikes me as a fantasy come true. When we finish, I feel grateful and caress her breasts lovingly.

“Want to move to the bed?” I ask.

“Let’s get some Chinese food,” she says. “I’m hungry.” She begins to dress.

I’m trying not to show disappointment that Nikki doesn’t want to lounge in our newfound intimacy, but I like Chinese food, too.

Lately, every Chinese restaurant in New York has prominent signs advertising spicy Szechwan tastes. My favorite is Hot Lips on Sixth Avenue between Tenth and Eleventh. Nearly a year ago I’d broken up with my last girlfriend at that very restaurant and hadn’t been back since. These women always seem to wriggle away and stride off beyond my grasp. I hesitate because I feel strange about having a first date where I’d had a last one, though Nikki doesn’t seem the kind of woman to indulge my superstitions. If nothing else happens, at least I can get a song out of it. Maybe something like: “Nikki was a stranger, full of mystery and danger. In one night I couldn’t change her and I lost her at Szechwan Sal’s.” Something like that.

“So, what’s your real name?” she asks after we order.

“Remember what happened to the Egyptian sun god, Ra,” I say. “He told his name to Isis, and she stole his power.” I figure I’ll fill her in on the classics.

“Nobody steals power,” she says. “People just give it away.” She softens a bit. “You’re probably right, though. If I had any power over you I’d have you running down the street barking at the moon.”

“You’re not the woman to do a thing like that,” I say, though I suspect she might be.

“You don’t even know me,” she says. Her smile has a cold shine, like the glint of sun on metal.

I get that sinking feeling again. I’d better not tell her too much. Then, I think maybe I should just get up and leave. That’s the safest option. Some woodshedding wouldn’t hurt. I have a new run I’ve been working out and maybe I should get myself in top form – especially when I have this audition coming up, you know, but I can’t seem to move off the chair.

“What’s this Nikki instead of Elizabeth,” I say, as I suppress the urge to run.

“Elizabeth is a loner,” she says. “Nikki has lots of friends.”

“Oh, yeah, I forgot about that,” I say. “What’s your last name?”

“Lawrence,” she tells me without hesitation. “That’s my father’s name. My parents have been divorced for a long time.”

“I’m the only one of our generation whose parents decided to stay together,” I say. “They did it just to mess me up.”

She shoots me a reluctant look, and refuses to laugh. “You country boys have all the luck,” she says.

“We deserve it,” I say. “We’ve never been exposed to the finer things in life.”

“You mean you’re sheltered?” she asks.

“I mean we think mostly about food and exposure to the elements.

She leans across the table. “Here in this city you can die of exposure, too

“How is that?” I ask.

“You’ll find out.” She sits back. “I’m not going to tell you.”

“So, why does your mother have a stage name?”

“Show business,” she says. “She hangs around stages, I guess, and she goes through stages. I don’t know, the studio gave it to her.”

“Would I know her name?”

“Thelma Firestone.”

“She’s famous,” I say, taking an extra breath so as not to gulp.

Thelma Firestone has been a Hollywood star for a long time. Even though she’s no longer a leading lady, she turns up in crafty roles once or twice a year. Until this moment I’d never considered that Thelma Firestone had a private life, with a husband and children, even that she might have a house to live in between movies. I look across at Nikki and find a resemblance to her mother. She quickly appears much more like an Elizabeth. I choke on a bite of General Chow’s very spicy chicken. Nikki hands me her glass of water and smiles a very warm smile, vulnerable in fact. That’s when I first get an inkling she likes me, though I can’t quite believe that she does.

“You probably don’t know my father. He’s famous in England. Martin Lawrence. He’s a stage actor, mostly. He made a few pictures here in the late fifties. That’s where he met my mother.”

She’s going to tell me everything, all at once. I see myself offering my name on a platter like the head of John the Baptist, and then her walking away without even looking back. It’s not that my name is Percival or Ellsworth or something, but I’m superstitious. I have to grit my teeth to hang on to it. I better get out of here I think, and get ready for that audition, but instead, I go along like my stomach isn’t bubbling.

“Rose Dreams, Violet Sorrows,” I say.

“You know it.” She’s surprised.

“One of my favorites,” I say. Actually, I’d found the movie sentimental, but an old girlfriend loved it, and every time the film played one of the revival houses, we had to go see it. I can’t remember for sure, but I think that’s one of the reasons we broke up. The movie was about an American nurse and a wounded English soldier during the First World War. I admired its anti-war theme. “A gutsy movie for the time,” I say.

“I can’t believe you know it,” she says. “I was conceived on the set. So my mother tells me.”

“I knew there was something extraordinary about that movie,” I say. “And so we meet.”

Nikki does not smile. “I hate show business,” she says.

“Me, too,” I say. “I’m only just singing in clubs until I can find a good office job.”

She gives me a wan smile, with plenty of wan. She’s right too, because it’s one of the lame jokes from my act when I feel the audience has gone to sleep during the last song. The joke gets mostly coughs and a few laughs from office workers.

“Do you ever see your dad?” I ask.

“He doesn’t come here anymore,” Nikki says. “I go there. He’s remarried and has a whole other family.” She does a stiff British accent. “He does ‘theater in Shakespeare’s England.'”

I prompt myself to laugh, even though a touch of sadness leaks through the lame accent. Then I make it worse by grinning at her.

“I’ve got to go,” she says, placing a twenty on the table. “This one’s on me. I’ll call you.” She stands up. No smile.

There’s a movie quality about the way she stands. As if my laugh is out of place and the director stepped in and said, “Cut.”

She turns and walks out.

“Don’t leave,” I want to say. “I’ll try that laugh again. Just give me a chance to do a little Stanislavski on my self-confidence.” The ghost of me runs after her but returns when I find myself shackled to the table and can’t make a move. I break open a fortune cookie. “Grasp opportunities to create the future,” the red script reads. “Lucky numbers 6, 7, 8, 9, 11.” I sit sipping my tea, thinking I’d drawn a ten. I feel as bad as when I’d broken up with my last girlfriend just a few tables away.

Now, when is that audition? Sometime in the future, I can’t remember. This guy catches my act, a big guy with a gut and a slouch hat with a couple of women in tow, he says, “Not bad, not bad. Give me a call. I might got a place for you opening for one of my acts, you know. Late spring, I got a tour.” He hands me a card. “Give me a call. Come by. Bring me a tape. I’ll send it on to my associates. Maybe we can send you out with one of our bands,” he says gesturing broadly seeming to impress the two tow girls. “You might just do. Give me a call,” he says, as he leaves. Which I do, and he wants me to come in to his office and give a little show for him and his associates. Sure, I say, just tell me when. I’ll give you a call, he says, but I never hear from him. But, I’m thinking to myself, he’ll call sometime. I’m pretty sure he’ll call. Now I’m counting on his call and I can’t sleep, so I get up and I write a song for Nikki.

Several days later Nikki calls. I’m surprised. She recites her phone number and address, and invites me up to the West Side to meet her cat.

“Sure,” I say. “I want to take you out to dinner. We could go hear some music or something. They have music on the upper West Side, don’t they?” I feel a burning need to pay her back for the Chinese dinner.

“Get dressed up,” she says.

“I have a corduroy jacket,” I say. “I may have a string tie, too.”

“Great,” she answers. “Get here at six and I’ll let you walk my cat.”

Nikki is wearing a robe when she opens the door. She leads me down a hallway past a large living room and into her bedroom. She removes my corduroy jacket. We kiss until her robe falls to the floor. We lay across her rumpled bed. She’s very loving and tender, and caresses my body as she slowly helps me remove my clothes. I try to be tender back, but I’m confused by her attentions. I’d wanted to take her out to dinner, hear some music and bring her back at midnight, maybe mess around then. My hands are unsure as I touch her. I’m awkward on the fast track. Finally, I pull her to me and kiss her lips. I hold her close against me. We make love. When we finish, she runs her fingers along my collarbone. She kisses my neck. I trace the bones of her face.

“Where’s your cat?” I ask.

“We just walked it,” she says.

“Oh.”

“You’re not very sophisticated, are you?”

“I’m from West Virginia.”

“Oh,” she says. Silence. I can’t tell if its embarrassment for the poor people of Appalachia, or if she never heard of it.

“We’re going to join the Union next year,” I throw out.

“Do you want to meet my mother?”

“No,” I say, without hesitation.

I begin dressing. Nikki stretches out on the bed naked without the least self-consciousness. I can’t quite comprehend how naturally immodest she is, I only know that I like it, though I find myself trying not to stare at her nakedness. She lies on her side facing me; her head is propped on her hand, pale white body, real as a Titian painting. I can see traces of her mother’s face in her mouth and eyes. She has a playful smile on her lips as she runs her finger along a crease in the sheet. She’s waiting for me to do something, but everything that comes to mind seems foolish and without sophistication. I want to tell her how beautiful she looks and how fine she makes me feel. I want to get back into bed and ravish her. I want to get down on one knee and propose. I want to reach into the whirl of my emotions and pull out a poem to dazzle her. However, I merely pull on my pants, feeling puzzled and relieved at the same time.

“I’m going to take a shower,” she says. “Want to join me?”

“No thanks,” I say. “I’d get my clothes all wet.”

She gives me another wan look and grabs her robe. “I’ll only be a minute.” “We’re going to meet my mother at seven-thirty,” she adds.

“You’re kidding.”

“Don’t worry.” She pauses. “It’s at a gallery. There will be lots of people there. She’ll hardly notice me, let alone you.” She tosses the robe over her shoulder and walks out of the room.

I sit on the edge of the bed and give the place a once-over. There’s a careless air about her bedroom. The walls haven’t been painted for years and peel at the corners of the ceiling. The hardwood floors are burnished deep dull brown. An old oak rocker sits in the corner piled with clothes. There’s a matching oak dresser with a mirror. On top of the dresser, small perfume bottles shine like glass fruit. I take a closer look. Next to a framed picture of her father looking very actorly, an ordinary color snapshot propped against one bottle shows Nikki and her mother on a beach somewhere. They are so relaxed it surprises me, like any mother and daughter. Nikki wears a bikini and her mother khaki shorts. Thelma Firestone has her arm around her daughter’s waist and manages to look very regal and at the same time genuine. She looks to be not much older than Nikki. They stand barefoot in the sand with an aquamarine ocean blending into the blue sky in the background. Nikki has one leg poised as if she’s about to take a step, maybe to walk right out of that picture. I find the pose sexy. They are both peering into the camera lens. I get the feeling they’re recording this moment to last across time, or perhaps trying to look into the future. Nikki appears especially happy. I pick up the snapshot for a closer look. For an instant I’m there, drawn into the picture; I see myself in the shot with them. After studying it for several minutes, I slip the photo into the pocket of my corduroy jacket, just to see how it feels to take possession of that scene. My heart misses a beat; I’ve gone too far. Before I come to my senses and replace the picture, Nikki strides into the room with her hair stringy and damp.

She dresses in a pair of jeans and a blazer. “Let’s go,” she says.

“We’re twins,” I say.

“We’ll be late,” she says.

“I thought your mother doesn’t notice.”

“She notices when I’m late.”

We take a cab across the park.

“This will be fine,” she says to the cabby and hands him a twenty.

“Hey, I’ll get it,” I object. While I’m struggling to get my wallet out of my back pocket, Nikki is already on the street holding her hand out for change.

“Hey, don’t worry,” she says, stuffing the bills into her purse. “We’re only fifteen minutes late. We can walk a few blocks. I hate to pull up in front of a place in a cab.”

“Yeah, me, too,” I say. “That’s why I take the subway.”

The attempt at a joke makes her smile. She takes my hand. We are in New York City, walking down Madison Avenue in the late March chill, past galleries with original Chagalls and Miros in the windows. A few people, perhaps coming home late from work, hurry down the avenue. I feel like the two of us are moving through some Hollywood set. The cameras whirr. The traffic sways along Madison. Magical shadows thrust out from the buildings. Just overhead the sky is bleeding the last color of sunset into twilight. I am very happy.

We turn into one of the galleries, where a young man who’s all eyes greets us. “We’re closed for an opening,” he tells us.

“The duality of art,” Nikki says. She makes her eyes big like Harold Lloyd or Joey Brown, and glances at me.

An older man in a tux rescues us. “Miss Lawrence, how nice to see you.” We are escorted into a bright back room with a polished wooden floor. “Your mother is in here,” he says.

A few people are scattered about the gallery admiring the pictures while a crush of people stand next to what I take to be a statue off to the right. Nikki pulls me toward them. The sculpture turns out to be her mother crowned in a glittering gold cloche over her platinum hair. Thelma Firestone wears a low cut black cocktail dress. A string of small pearls circles her neck. She’s quite a beautiful woman, tall and assured, with no need for a camera to make her glamorous. She stands next to a smallish man sprouting a gray goatee – the artist, no doubt. He wears a beret, checkered shirt and string tie. The actress is doing her best to shed the attention of the group onto the artist, but her adoring fans won’t let her. I’m amazed and jealous, I suppose, at the well-dressed people dangling themselves in front of her like limp strips of flypaper. We stand on the outside of the circle. When Miss Firestone turns to us, she gives a quick open-eyed look to her daughter. I immediately feel protective of Nikki. Did her mother glance at her watch? I may have mistaken the gesture. This is my first glimpse of a truly famous person – a woman with a face that would be recognized most anywhere, but then is that really the face I recognize from movies. I’m surprised that she’s different from the screen, an unexpected dimension of depth or mystery. Her very presence creates intrigue.

As more people enter the gallery, we are forced closer to the actress. She has skillfully formed a receiving line in the round, saying a few words to the artist and then a few words to her fans. After facing one direction, the actress turns with the practiced movement of a duchess, subtly nudging her subjects toward the artist. After a time Nikki and I are close to her mother, who ignores us until she judges the moment is right. Nikki has taken my hand and holds it so that her mother cannot help seeing us. I alternate between glum and grinning, hoping Nikki’s mother won’t attempt eye contact.

Thelma Firestone reaches across the small chasm to take her daughter’s hand with such resolute movement that Nikki lets go of mine.

“Elizabeth,” she says drawing her daughter to her. “I didn’t think you would actually show, my dear.” She turns to the art patrons. “This is my daughter, Elizabeth Lawrence.” At the same time she looks me up and down before she hauls Nikki to the other side of her. “Look who’s here,” she intones. “Stephen came all the way from Montauk.” She moves toward Stephen, a tall young man in a dark suit with Lord Byron hair, standing at the other side of the circle. As the actress moves, the crush of people follows her and cuts me off from mother and daughter. I recognize Stephen as one of the crowd Nikki had been with that first night at the club. I feel abandoned or relieved, I can’t tell which. I clasp my hands and rock back and forth on the balls of my feet, pretending not to notice.

I look across the room at the paintings and walk toward the one that appears most inviting. I move closer before I see they are alike. Among the cool pastel colors, thickly laid on with a palette knife, are small orange, green and blue butterfly-men hovering above abstract landscapes of vague oceans, sometimes mountains or cities. The little men with wings are the same in each painting, only the locales and colors change. Some paintings have swarms of these little men and others, two or three. They are miniatures of the artist himself. I try to lose myself in the paintings, crawl in there and hide. I would give up my very fine Martin guitar at this moment, just to escape on wings with one of these butterfly men. I am about decided to turn and make it to the door, or crawl into the corner of one of the paintings, when Nikki takes my arm.

“My mother is so strange,” she tells me. “You’ll get used to her.” Her eyes light so that I have to blink.

I look across the room where her mother continues to hold court. I feel moisture on my palms. I don’t have nerves this bad before I go on stage.

“She wants to meet you,” Nikki whispers, pulling me toward her mother. “Come on.”

“Mother,” Nikki intones. “This is Floyd Webber.”

Her mother turns from talking with the artist. She sizes me up consciously for her daughter’s benefit, gives me a bemused half-smile and extends her hand. I consider for an instant whether to kiss her hand or show her my version of Stephen’s college fraternity handshake. Instead, I take her hand lightly and give her my warmest smile, which is the one I use on the rare occasions when I’m invited by the audience to do an encore. I must have done the right thing because she says, “Floyd, you look very familiar.” I take this to mean she recognizes me from another time, another city, perhaps Chasens or last year’s Oscars. She lets go of my hand quickly and introduces me to the artist, Hiram Wirpal. Nikki introduces me to Stephen who shakes my hand with an animal grip and gives me a cool look down the side of his aristocratic nose.

Before we have a chance to chat, Nikki tells her mother that we are going to a party.

“Oh,” Thelma Firestone says, with one of her movie smiles. “I was hoping we would all have a bite together, but I suppose Stephen will see me home.”

We all smile in unison. A moment or two later, Nikki steers me to the door.

“I hope you don’t mind,” Nikki says as we walk down Madison. “I hate to go to restaurants with my mother. She’s always the center of attention. It’s a pain. All she really wants is for people to know she has a daughter.” She only goes to Sardi’s or the Russian Tea Room, anyway.

“I don’t mind,” I say. “I’ll miss Stephen, though.”

“Everyone whispers that Stephen is my mother’s lover, but it’s not true.” Nikki says. “He was mine at one time. We went to college together.”

“Oh,” I say. A remark or two comes to mind, but I manage to keep myself quiet.

As if she heard my thoughts, Nikki stops walking and releases my hand. “My mother works very hard. Everyone wants something from her. She can’t trust anyone. She’s providing Stephen a place to live and work. She needs comfort sometimes, too.”

“I understand,” I say.

“No you don’t,” she says. Her eyes narrow and darken. “You’re a provincial.”

After a silence, she takes my arm. “I know an Indian restaurant not far from here. It’s dark inside and we can eat spicy food slowly. And drink sweet lassies,” she adds like a little girl.

After dinner we go to Nikki’s. She leads me into the living room, which has the same shabby elegance as her bedroom. We sit on the velvet couch and kiss for a while. She won’t let me touch her breasts. I’m puzzled as she draws her legs up under her and nestles in my arms like a kitten. “You can call me Elizabeth,” she says. “You can even call me Beth. My father calls me Beth sometimes.” She talks in little silly spurts and when I make a move toward the bedroom, she simply says, “No, no. You have to go soon.”

Before midnight, she pushes me out the door. When I protest, she kisses her finger and puts it to my lips with a smile. She looks at me deeply. “Call me tomorrow,” she says. Then she closes the door. I feel like Mickey Rooney in “A Date with Judy.” I’m all black and white. I walk down upper Broadway toward the subway. The Asian markets are open, spilling fragrant bins of fruits and vegetables in front of their shops. People roam the streets. I remember that’s why I moved to New York in the first place, so I would never be lonely. And of course, to fire a shot at fame or whatever you call the dream of fortune that flies on butterfly wings. I wonder if this is my shot. No, I tell myself. I’m the music man. Tin Pan Alley. Don’t forget about the audition, Floyd – don’t worry, man.

I start down the subway steps to discover the gates are closed. The dark shadows of the closed subway enfold me with the surprise of a dream. Locked out, I shudder for a moment. I’d forgotten the threat of a strike loomed over the city for the past several weeks. Tonight must be the night. I touched the lock that held the chain around the gage. I’d completely missed the warning that gates would close at midnight. Where is my head anyway? I have the choice of walking the hundred or so blocks to the Village or taking a taxi if I can find one. I opt for the cab. What the hell, I think, I’d just fallen in love with Thelma Firestone’s daughter.

When I arrive at my apartment, I feel in my jacket for my keys and discover the snapshot of Nikki and her mother. I put the photo in the top drawer of my bureau along with my feelings of shame. I decide to put the picture back exactly where I found it next time I go to Nikki’s place.

Every time I open the drawer I’m surprised to discover that the photo is still there. Each time, I pull it out and study the two of them. I can’t believe the fascination I find in such an ordinary photo. I notice that her mother’s eyes are the same color as the meridian where the ocean and sky meet in the picture. The colors remind me of the paintings at the gallery and the funny butterfly-men. I keep making the decision to return the picture, but somehow I always forget or remember when I get to Nikki’s apartment.

“I’m going back to school,” Nikki says for the second time this evening. We’re walking out of a bookstore on upper Broadway.

“Oh yeah,” I say.

“I’m going to get serious,” she says. After a thoughtful moment, she says, “I’m going to go to law school. My father’s sister is a barrister in England.”

“Really,”

“That’s about as serious as you can get, I think.”

“Do you ever think about getting a job?” she asks. “Don’t you ever think about giving up this folkie business? Singing made up songs and telling lame jokes. You went to college.” Nikki tilts her head and narrows her eyes in a gesture that charms me. “Oh, I’m just joking,” she says.

We head up Broadway.

“Not yet,” I shrug. “It’s not like I don’t have any talent,” I say. I’m hoping she’ll say I have lots and lots of talent, but she only pauses for the silence to rebound.

“I hope you know what you’re doing,” she says. She takes my arm as we walk across 96th Street. “I forgot. You’re not the serious type.”

“I wrote you a song, ” I said to change the subject.

“Sure,” she said.

“Really. I’ll sing it. I’ll sing you the chorus”

“Right here on Broadway, just like the movies.”

“Just like the movies, I say, and sing with my voice cracking and my heart pounding:

Love is hard to find in New York City

For a ragtag clown from West Virginia

Riding the subway up and down, eyeing the buildings up and down

Good for a laugh and a miracle perhaps

Love is hard to find for a clown in New York City

Hold onto the miracle you’ve found in New York City.

“Very nice,” she says. “Very nice.”

“Do you like it?” I ask.

“Oh, yes,” she says. “I like it. I do like it.”

“I’ll sing the whole thing for you, with the guitar, and all.”

“I like it,” she says. “I really do.”

We walk on in silence. I can’t tell if she liked the song or not. Then I think about our conversation and I can’t help wondering to myself if I can love a woman who intends to go to law school. I mean, it’s the furthest thing from my future reckonings. “Songs and jokes push the world along, too, “I say.

“Oh, I have no doubt,” she says. “But we’re not pushing, we’re trying to live.”

We’re at her apartment house door. It’s after 11:00, the mist from the Hudson hangs in the doorway, steaming off the cement and soaking the columns and cornices in a glow from the city lights. We could be in London way back when the sound of carriage wheels clanked along the cobble streets. Maybe Nikki’s father is watching us in one of his dreams. Someone’s watching us I feel. The moment is spooky, but also very beautiful and full of possibilities just like this romance.

“Want to come up?” Nikki asks.

“Now?”

“You could spend the night.”

“Is that an invitation?”

“Well, what does it sound like? All right you can just call me tomorrow.”

“No, No,” I say. “I’d like to come up. I’d like to spend the night.” We rarely spend the night together. We usually make it early in the evening and then say good night at the door. Nikki does not sleep well when there’s another body in the bed – at least that’s what she tells me.

“You sure?” I ask. My tone is neutral. I’m ready to kiss her goodnight and head downtown, though I’m hoping not to.

“Oh, I’m sure,” she says. Beside, there’s the strike. You’ll never get a cab.”

“I’d like to stay,” I say. I’m feeling awkward. I’m not sure if I want to stay. I often feel liberated when I leave her late at night and thoughtfully ride the train home, still filled with all the possibilities of our romance. If we start spending the nights together, then that’s some type of move I’m not sure I want to make.

“Well,” she says. “Shall we go in?” Her voice is formal. We both maybe are thinking that this is getting to be more than just casual. “You don’t look like you really want to,” she says.

“Of course I do”.

Upstairs, she turns the lights low in the living room. We make out on the couch before she pulls me into the bedroom and then we make love a little different than usual. We’re more deliberate and tender – more caring. I’m feeling that I’ve never been this way with a woman before or could ever imagine being the same with anyone else and my eyes and my mind and my fingers are filled with her light and her images and her touch. It’s a mysterious time, as we lie there on the bed in each other’s arms, drowsy and not wanting to fall asleep. I’m closer than I’ve ever been to another human being. I’m thinking to myself, don’t move, don’t move. If you do, the bough will break.

“You’re quite a lover,” she says.

“Really,” I say. I think she’s trying to build me up, the way women are supposed to. “You’re just saying that.”

“No, I mean you’re different than anyone else. You’re better.”

“Better.” I say. “Like a race.”

“Well I don’t mean a comparison. You’re the best,” she says so drowsy and snuggles close.

“You gonna respect me in the morning?” I ask.

“Ah, huh,” she says. “Lot of respect.”

“I can rest assured,” I say back. We’re drifting off.

Then she comes awake, struck by a thought. “I’m missing a special picture of my mother and me from a vacation last summer. I like it a lot. I thought I left it on my bureau. Did you see it?

“No,” I say. “I didn’t.” She sinks back down in my arms and we’re asleep.

The next morning, just after eight, the phone rings.

“Thelma wants to come over,” Nikki says, throwing the covers off. “She has a taxi waiting. Get up, get up. She’s bringing me lighting fixtures. She only lives across the park.” She pushes me out of bed.

“What,” I say.

“She’ll be here in a few minutes. Oh, she’s a sly one. She’s been threatening to give me those things for a year.

Is this the only time she could find to deliver them?” I ask, still groggy.

“No, no,” Nikki says, looking at the clock. She wants to see if I’m sleeping with you. Get dressed, get dressed,” she says. “You’ve got to go.”

“Go?” I ask, standing barefoot on the cold hardwood floor.

“Put on your pants,” Nikki says, flinging them at me. “Come on,” she says. “I don’t want her to walk in on us. Damn you, Thelma.”

“Thanks a lot, Thelma,” I say, hopping on one foot to get a sock on.

Nikki pulls a robe over her shoulders. She leads me from the bedroom, through the living room and into the kitchen where a door in the pantry leads to the hallway. Nikki referred to it once as the “tradesman’s entrance.” I remember thinking that is an odd phrase for an enlightened woman, and pictured a whole gang of carpenters, plumbers, window cleaners, food deliveries and maids trooping through that door over the years. Now, I’m following them out.

“Use the stairs,” Nikki says as she pushes me. “She might be on the elevator. Come back in an hour. She never stays long.” Nikki gives me a warm, lingering kiss.

“Drama,” I say.

“I hate show business,” she says. “Go, go, go.”

I run down the first flight of stairs feeling like a fugitive in some old western. I slow on the next landing, remembering Nikki’s kiss. On my lips it feels like a movie kiss, bestowed before the hero slips away from the posse. I open the door a crack and look into the lobby. All clear. Nikki, it occurs to me, is playing a role in her mother’s movie and I’ve become an actor in Nikki’s movie. Not only am I excited; I want a bigger part. I can’t believe myself.

What if her mother catches me, what then? I cross the side street to a Greek coffee shop on the corner and sit in a booth with a view of Nikki’s building. I hold my breath. My vision blurs. Maybe the coffee will help. I check to see if I’m fully dressed. The waiter who serves my coffee has no idea I’m involved in a drama while his other clientele are merely going through their regular Saturday breakfast routine. I order a bagel. While others read their papers, I keep my eyes peeled.

I’m lingering on my third cup of coffee when I see Nikki’s mother come out of the building. She poses on the top step as if she were waiting for a camera to catch up to her. She wears dark glasses, a blue silk scarf over her head and a suede trench coat with the collar turned up. She moves down the front steps appearing quite ordinary.

In the same foolhardy manner that I slipped the picture of Nikki and her mother into my pocket, I pay the check and walk out the door in time for Thelma Firestone to spot me. I tell myself that I’m timing my walk across the street to miss her. My heart pumps an extra few beats when she pauses to watch me cross. I can’t make myself turn back, and I pass the famous actress on my way up the steps. Her cheeks are white without makeup. I remember the glitter of her gold hat and the pearl necklace the night I’d met her. She appears sinister to me now, her lips thin and pale.

She removes her glasses and touches the frame to her chin. “I know you.” She begins to smile, but stops. “Am I mistaken?” she says with a shrewd look, as if she’s discovered what she’d come to find. “You’re Elizabeth’s friend.”

“Yes,” I say.

“I’m afraid I can’t remember your name.”

“Floyd,” I say.

“Oh, yes. At the gallery. You were taking Elizabeth to a party. And are you taking her to a party at this early hour.”

“I stopped by to take Nikki for a walk in the park,” I say.

“Oh. How nice,” she pronounces. “My daughter who hardly ever gets up before noon is going for a walk before the birds start chirping.”

I look away for a moment at the passing traffic.

“Well,” she goes on. “I do suppose if a handsome young man asked me for a morning walk, I’d have to accept, too.” She flashes me a most glamorous look. “I only live on the other side of the park. It’s quite lovely over there. You should come and visit.” Her eyes are very blue and clear as she looks at me. Nikki has the same eyes, though her mother’s are quicker. Thelma Firestone renders me another smile. She opens her purse and pulls out a card and writes her phone number on the back and hands it to me. “Oh, well,” she says with a feigned touch of sadness. “I must go. Nice to see you again…Floyd.”

I’m stunned in the morning sun, as the actress moves to the street and hails a cab. Did I receive a serious competitive invitation from Nikki’s mother? I hear my head calculate the difference in our ages. I remember her face as I walk into the building. Some set of her jaw, the quick smile strikes me as an attempt to win me over. Show business.

Nikki is still in her robe. She apologizes for her mother. “She’s trying to catch us,” she says.

“What will she do if she catches us?” I ask.

“Nothing,” Nikki says. “She disapproves and then never mentions it until a strategic moment in our negotiations.”

“Strategic negotiations, eh?”

“When she wants me to do something I don’t want to do, and she comes on with, ‘And that Floyd character that you insist on sleeping with,'” Nikki does a fair imitation of her mother. “‘He’s positively from the other side of the earth. Is this why I sent you to school in Switzerland, and now you’re throwing your life away and you won’t even do one small favor for the mother who bore you.'” Nikki stops, out of breath. She always gets her way, one way or another.

“You mean this has happened before?”

“She caught Stephen and me doing it once.” Nikki turns away.

“Sorry, but I ran into your mother as she was coming out,” I say.

“How could you, Floyd?”

Though she sounds exasperated, she doesn’t appear upset. “I didn’t mean to. She was quite pleasant.”

“Of course. It wouldn’t be good form for her to be any other way.” Nikki says. “Didn’t she want to know what you were doing here?”

“I told her we were going for a walk.” I don’t mention the card with her mother’s phone number.

“Oh, yes. I’m sure she bought that.” Nikki dismisses her mother with a wave of her hand. “The first thing she did when she arrived was go into my bedroom and open my closet. ‘Oh, I only want to have a look at your wardrobe dear, to see if you need anything.’ I hate show business,” Nikki says.

Nikki brings me coffee. We sit on the couch. She lays her head in my lap. “I’m going to be a teacher,” she says. “I’m going to teach kids in the Bronx or somewhere. I’ll teach them how to read. I want them to care about the real things in life. I want them to be like you,” she says. “But I want them to read books, not newspapers.”

She sits up and puts her arms around me. She admires me, sort of. We are together in a tender moment. I feel secure in her affections. I decide to tell her, to come clean, to clear all barriers between us.

“That lost photo of you and your mother,” I say.

“I don’t know where I put it.”

“I took it,” I tell her. I immediately know that this confession is a big mistake.

“Oh,” she says softly. She sits up. “You took it. Why?”

“To get closer to you, I suppose.”

While she digests this information, Nikki strikes an indignant pose from the western where the hero gets slapped by the schoolmarm.

“You stole a snapshot? Why didn’t you ask me to autograph it for you?” She takes a pillow and places it across her lap. “It was one of our happiest times together.” Nikki stops for a moment.

“You must not understand,” she says, incredulous. “I think you really don’t understand, or you wouldn’t have done a dumb thing like that. It was the one time I can remember since I was a small child that we spent any amount of time together. Almost a week. Out at her place, with no one else around. You don’t know how hard it is to get my mother alone for an afternoon, let alone nearly a week. We’d been fighting and fighting over the phone. We fought until we couldn’t fight or talk anymore. Then, she asked me what I wanted and I told her a whole week. She had almost a week before she had to go to the coast. She said, ‘Yes. Of course I have time for my only daughter. This is after more than 20 years. And she said it so sweetly, ‘Of course I have a week for my only daughter. Shall we go away? Where would you want to go?” But I told her, right here. Right in your house on your beach. No parties, I told her, no friends dropping by at midnight. No have-to-meet-chas in New York. Just the two of us, like when I was a kid. And she gave that to me. Of course that was several years ago. But for that time, we were like mother and daughter, again. No fighting. Just like we loved each other. She gave me a true gift and we only have a few pictures. Some guy who wandered down the beach. We asked him to take our picture. He snapped us and handed us the camera and left, never even recognized my mom.

“I didn’t think you would miss it,” I say. “I didn’t sell it to a movie magazine.”

“I’m grateful for that.” She pauses. “How about my underwear. Did you get a bra so you could practice unsnapping it?”

I feel a hot flush come to my face.

“Did you go through my drawers and find my bank book?” She says this in a practiced way, as if the moment has been rehearsed.

“I better go,” I say.

“I suppose you better,” she replies.

I walk down the hall toward the door.

“I’m sorry I act so much like my mother,” she calls after me. “I can’t help it.”

I find hope in her tone. Maybe she’ll get over this.

Why didn’t I just stick the picture back in one of her drawers so she’d think that she misplaced it? What a dolt, I accuse myself. Why had I told her? I’m out on the street with my hands in my pockets. Just a few minutes before I’d talked to Thelma Firestone, confident of her daughter’s affection. Now, as if her mother has cast a spell on Nikki, I’m separated, abandoned by my own luck. I think of my first dinner with Nikki at the Chinese restaurant.

I walk to the Village mumbling to myself. First, I have a dialogue with Nikki. Then, conversations follow with Nikki and her mother, with Nikki and her father. I manage to bring her mother and father together again. I’m a hero. Her mother insists that we accept her beach house where the picture was taken. Oh, it’s all a lark. Maybe I would visit Nikki’s mother across the park.

When I arrive at my place, I go directly to the bureau and take out the snapshot. I look at the same bright faces that I’d been studying. They are dimmed. I detect a strain at the corners of Nikki’s mother’s smile. Nikki doesn’t come across as happy as I’d once seen her. Maybe this is some backward version of Dorian Gray. Even the background has lost its pastel luster. I brood on what to do for some time. I pick up my guitar and get lost in that for a while, and then dinnertime and I open a can of soup. I brood some more until about 7:00 when I can’t convince myself to wait until tomorrow. I’m lucky to find a cab uptown. Outside the lobby of Nikki’s building I pick up the phone and dial her number. “Go away,” she says when she hears my voice.

“I’m returning the picture,” I say into the black phone.

After several long moments, the door buzzes open. The elevator takes forever. I knock. When there is no answer, I slip the picture under the door and wait for a few minutes. I’m waiting with my heart beating. She only has to open the door a crack. I’m sure that if she sees my contrite expression, she will forgive me. I hear a little shuffling by the door. I think maybe she’s picked up the picture. I wait expectantly. I wait longer as the expectation fades. I hear maybe a rustling sound moving away from the door. I stand alone in the silent marble hallway. After more time, I turn and walk down the stairs and outside. I stand desolate and alone. I am angry. I’m hurt. I’m confused. A string has been cut inside me. Something final has occurred, but I keep thinking maybe I can repair it, make it different, make it better. Heal it. The picture of Nikki and her mother flashes in front of me. Standing on the street, I look back at the big stone-gray apartment building with its lintels and peaked windows. “Stella!” I want to shout out in a wail of agony. “Stella!” I turn away.

Leaves have busted through on the spindly trees along West End Avenue. Walking over to Broadway, I look through the darkening night toward the park and the East Side beyond. Spring has arrived with a haunting, close feeling; the air is warm and humid, almost like summer as the evening approaches and twilight sparks across the Hudson. I look over to the park again and can just make out some trees, but it’s too far and I don’t feel like walking. I feel like I’m in a state of shock, like someone punched me hard in the stomach and then hard again to the face. I’m numb and kind of sick to my stomach. I head downtown toward the subway stop at 103rd.

Then, coming out of my stupor I realize there are more people than usual on the sidewalk. Oh, I think, maybe they’ve heard of my break up with Nikki and they’re coming to tell me how sorry they are, and then I remember the strike. Many people are walking in earnest, with stoic looks, taking their own space on the sidewalk like they might on the subway. I pass the Asian fruit market with sweet smells, a pizza place and a bodega, where the bells jangle on the door. A breeze swirls shreds of paper along the sidewalk. I look at each face for some clue as to what just happened, where I am in all this, but no one looks back. The long faces and determined strides present nothing for me to read into my own predicament. I feel suddenly aware and perceptive like I could make up a story about each and every face I pass and become part of their lives instead of my own.

When I get to 103rd, I go down the gloomy steps though I know that the gate is shut. Little chance of getting a cab. I’ve got to walk, I guess, or maybe go across the park and look up Nikki’s mom; my mind doesn’t want to work. I can’t get past the eerie, merciless thoughts that I blew my whole life away in one stroke. I’m lost and afraid and unable to make any sense. I’ve never felt this alone and I’d do anything to change my fate. I bang my palm against the gate and the cyclone fencing rattles all the way down to the dirty cement but holds firm. The rusting chain is fastened with a padlock. I bang it again and notice that there’s some play where the chain’s been fastened. I pull at the gate and it opens a few inches. I see where the padlock is holding the chain kind of loose. I work the chain, and pull the lock down and under and it lets out a few more links and when I pull the gate this time, lo and behold it comes open a few more links and I think maybe I can squeeze myself through the opening, but I can’t, so I keep playing with the chain, pulling and rattling the heavy lock and untwisting the chain and I can see it’s been put up in a hurry and there’s a few more links I can dislodge and so fooling with it for five or so minutes, I get the fence loose enough so I can barely slip through the opening and there I am inside the shut down subway. Very eerie and creepy. I venture a few steps down inside and make out the shadow of the token booth with a faint light shining through the wire window. I walk tentative down the dusty steps to the booth level where I see the glint of dull light shining off the turnstiles. It’s not so dark as I thought. The fading daylight, bright against the gloom of the empty subway, still comes down from the steps after me. Beyond this are small pale lights low along the rough cement walls. I feel oddly comfortable in the cool musty darkness. The deserted space matches my insides – huge and empty and devoid. The cement floors are creepy without the shuffle and grind of feet. The silence is laid down like a carpet; not even my own footfalls echo as I walk to the turnstiles and peer further into the station. I squeeze through one turnstile and walk a few steps to the platform. Every ten or fifteen yards a dull yellow light floats across the riveted beams and disappears over the tracks. I feel like I’m swallowed whole as Jonah, surrounded by the insides of this gigantic girdered whale. The drenching shadows draw me in. Further down the track, I see an abandoned train near the end of the platform. The doors are open. The strikers must have stopped the train at midnight, made an announcement for the passengers to get off and herded everyone out of the station before they shut the place down. Nothing had moved for more than a week. I walk to the edge and look over to see if I can make out the third rail. The darkness feels soupy. I hear the skittering of rats, but it may only be my ricocheting thoughts. The dense air causes me to gulp. I begin to feel easier, like what happened with Nikki is far away and maybe not so bad, after all. Never meant to be I tell myself. After all the times I’d broken up with a woman, I knew that any experience I could put between myself and that breaking point, the better I would feel. The cool air and dull lights make the place kind of calming. I walk further down the platform to the last car and through the open door. Small dim reflectors glow red like science fiction fish. If such things as ghosts exist they must live down among the subway cars. I almost feel their presence as I sit on a long metal seat. I look around the empty car with a new appreciation for how it’s put together like a sculpture. Slowly, I become aware, maybe after a long time, watching my thoughts swim through my mind, but without the usual urgency calling me to do something. I hear a sound, like the swaying and knock of metal, then I hear it again from a different direction, and every few minutes a small click or a knocking or a slight shudder rings out like the empty subway tolled its own clock ticking in a different rhythm.

After a time, I walk through the train to the first car and peer down the tracks toward the next station at 96th St. I think maybe I can climb out on to the tracks and walk to the next station and find another car and stay there for awhile and then move on to the next station. I sit in the driver’s seat and look on down the line. Who knows what I might discover if I let my mind follow that track and wander among the shadows and ghosts.

I look down the long track curving off to the left in the dim glow. The glint of light draws my eye like perspective into a painting. With the same reckless whim that overcame me when I slipped Nikki’s picture into my pocket, I leap to the door, hang by my left hand, and swing around to the front of the train. I jump into the darkness and land hard. One foot hits a tie, and the other foot wedges into the gravel. I almost fall. Regaining my balance, I proceed to walk down the dark tunnel toward the next station.