Talking to Ted Wells (Ethiopia) author of POWER, CHAOS & CONSENSUS

Ted, where are you from in the States?

Ted Wells (Ethiopia 1968–71)

I was born in Boston, Massachusetts and raised in a small town called Sharon 20 miles south of the city. I started a 5 year degree in Architecture at the University of Oregon in Eugene, but finished it at the University of Colorado in Boulder, where I met my wife-to-be, Helen, who was born in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, but had moved to Colorado just before I arrived.

Why the Peace Corps?

I was strongly opposed to the Vietnam War and would have emigrated to Canada with my wife of ten months had we not both been accepted into the Peace Corps immediately after I graduated from university. Thankfully, my Draft Board accepted this as an alternative to Vietnam.

Why Ethiopia?

We would have accepted any assignment anywhere in the Peace Corps, but Community Development work in Ethiopia was the only choice we were offered. Helen had grown up on a small farm in eastern Tennessee and was training to be a nurse so had some relevant experience.

I’m not sure why they thought it was a good fit for me as my degree seemed of dubious value, except I had spent my summers working as a camp counselor and caretaker in the Rocky Mountains. I must say, however, once in Ethiopia we quickly realized we had been given the opportunity of a lifetime to live and work in a part of the world and in an ancient culture few people in the woochi agger or outside world knew anything about.

How did you become a Community Development PCV as most PCVs to Ethiopia were and are teachers?

Out of 250 volunteers in our group going to Ethiopia, only a handful were not teachers. When we first arrived in Ethiopia we were sent to Gondar for a week as trainee community development workers to watch other volunteers teach prostitutes how to embroider “his” and “hers” on pillowcases.

We learned how it could help poor women take up another more respectable career, but came back to Addis Abeba quietly admitting it seemed like very depressing volunteer work. We hesitantly asked our Peace Corps boss if there was something else we could do instead, to which he then asked if we’d like to help a small group of farmers from the highlands establish a new town in the remote, malaria-infested Rift Valley jungle in southern Ethiopia instead. We both instantly jumped at the idea. At the time, the area was known locally as Shileh, but it eventually became known as “Menze Seffer” after the Amhara Menze people who settled there.

You published two books in 2012. The first was The Old Man in the Bag . . . And Other True Stories of Good Intentions. The second is entitled, Power, Chaos & Consensus — can you give us a (short) explanation of what it is about? — and where did the Peace Corps fit into this view of the US?

Almost all decisions in our tiny Ethiopian new town of perhaps twenty men and an equal number of women and children were made simply by everyone gathering together, discussing the options facing them and then collectively choosing one. Decisions were not made by majority vote, which would have left out half the group, but by a form of consensus. Not everyone always fully agreed with the final option chosen, but choices were discussed until there was almost no remaining disagreement. It was a form of group decision-making that was considerably more peaceful than what was happening in the US at the time.

Almost all decisions in our tiny Ethiopian new town of perhaps twenty men and an equal number of women and children were made simply by everyone gathering together, discussing the options facing them and then collectively choosing one. Decisions were not made by majority vote, which would have left out half the group, but by a form of consensus. Not everyone always fully agreed with the final option chosen, but choices were discussed until there was almost no remaining disagreement. It was a form of group decision-making that was considerably more peaceful than what was happening in the US at the time.

In the 50 years since then, I’ve been trying to figure out how a variation of this same system could be used to comprehensively, peacefully fix the serious mess humanity is now in on this planet. I’m now working on the third edition of my book about it, now called Power, Chaos and Consensus, but when this edition is finished I’ll probably change its name to “How to Fix the Planet”.

The “solution,” I think, is not a new religion, a philosopher’s vague theory or another utopian dream. It is simply a plan; a voluntarily imposed, collectively agreed plan developed from the many ideas I’ve encountered over a lengthy professional career preparing a variety of planning documents for many different governments all over the world.

This plan uses a form of consensus decision-making that works in large groups and avoids the potential problems created by narcissistic participants. It would let any size group of people anywhere, even entire countries or continents, gradually, peacefully, update their own local civil laws to (among other things):

-

- Allow many autonomous communities to live in the same area together peacefully, . . . e.g. Arabs and Jews living together, but each in full control of their own lives and cultural assets.

- Ensure environmental and social impacts are considered in all political decisions.

- Remove social media manipulation and fake news from political decisions.

- Ensure gender equality and minority representation in all political decisions.

- Remove the ability of political representatives to buy their own selection.

- Avoid election cycles that force short-term solutions to long-term problems.

- Remove the use or threat of force to resolve inter-community differences.

- Ensure the rapid, peaceful implementation of political decisions.

There are actually parts of this plan already in use in many parts of the world today, including the USA, The Netherlands, Spain, India, and a dozen other countries.

You write that The Old Man in the Bag is a ‘prequel’ to your Power, Chaos & Consensus, how do you mean that? Just because you were working on that book as well or another reason? Explain that?

Many of the personal experiences in Ethiopia that I write about in The Old Man in the Bag are about the use or misuse of power, particularly my own. Sometimes that power was completely invisible to me and always unintentional, but it still affected others. The short story named after the title of the book, for instance, is about me trying to compensate a village woman for something I had accidentally done to her, but because of the power unintentionally attached to it, the compensation I offered turned out to make her even angrier.

My second book is also about power; specifically about how to remove it from all political decision-making. At the moment, only a handful of democracies on the planet have figured out how to remove it from their decision-making. Most choose to split all their decisions into black and white options that force politicians to chose a side where only half the people can win. It unavoidably creates losers in the process where none need exist. My second book begins with the lessons I learned in Ethiopia and is about how to make decisions where everybody wins by deliberately, peacefully, removing power from the equation.

You were an early (if not the first) PCV to have your type of assignment. What were you able to do in your three years with development. Also, explain (in short form) where these towns were for RPCVs from other countries.

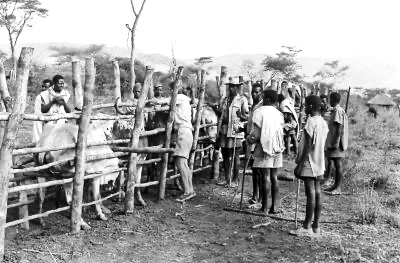

Helen and I just went back to Ethiopia after an absence of 50 years and discovered how little impact we had there in the end. During our first two years helping to establish a new town in the jungle of the southern Rift Valley we had taught villagers how to build termite-resistant houses, run a village store, taught health and hygiene, grew new demonstration crops, treated their malaria, and vaccinated their cattle.

However, just as I had predicted, the new town hardly grew at all during the intervening 5 decades despite all the forests around it now cleared and turned into very productive farms.

I had thought this would happen because the new road built down through the valley 50 years ago (while we were there) completely bypassed the village. But the real reason it didn’t grow was because the villagers were all Menze Amharas and their known association with Haile Selassie persuaded the Communist Derg (the military junta that ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1987) of Mengistu Haile Mariam to completely ostracize them. Thankfully they weren’t among the half-million other Ethiopians who suffered a much worse fate under the Derg, but the isolation and poverty we saw on our return there was still extremely depressing.

The only bright spot for us was that one of the old village women still living there instantly recognized us despite our ages and looks, and gave us both a warm welcome back. She then recounted with laughter for all those who quickly gathered around, many of the stories of our life in the village now described in Old Man in the Bag.

Our third year in Ethiopia was spent with the nomadic Dasonich beside the Omo River down in the southwest corner of Ethiopia just north of Lake Turkana. There is now a new paved road into the area where it had once taken us three long days on the back of a 4WD police truck to get there from the closest airport.

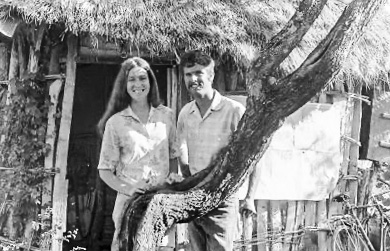

House on the Omo

Disappointingly, however, the new town I had designed never materialized, and the unique house Helen and I had built there for government workers was gone almost without a trace. No one we knew there was still alive, but we did manage to find part of the roof of the house we had built now covering some agricultural equipment in the new town that now existed directly across the river from where we had been.

How did Helen find ‘work’ with your resettling around Ethiopia?

During our first two years, Helen never stopped working as a teacher and a nurse, as she made friends easily. During our third year, neither of us knew the local language so she helped me build the new house for future government staff and created a large food garden using water from the Omo River.

Helen in her garden

Several times over our third-year intrepid tourists arrived at our camp by 4WD truck or inflatable boat, expecting to find a town and a grocery store. The only town within hundreds of miles of us, however, was a collection of 20 grass huts for the police protecting the border and stopping inter-tribal warfare. It was erected 7 kilometers out in the desert to keep away from the mosquitoes and malaria by the river. The Police Post was called Kelam and was often found on maps of Africa at the time.

We had brought in enough food by truck to last us a year and allow us to build a 4 room house for future Ethiopian staff, so from Helen’s garden, we gave visitors any food we could spare. Once while I was gone surveying another new town (also never built) she was asked by the police to temporarily house several “tourists” who had blazed their way into Ethiopia from the south without the necessary papers.

Helen vaccinating cows

What was the reason you stayed for the third year?

By midyear of our second year, the US had enacted a new draft law that selected recruits by a lottery system based on their birthday. It turned out my birthday was near the bottom of the list and I no longer feared being drafted.

However, the Community Development Ministry of the Ethiopian Government liked our work during our first two years in Shileh (or Menze Seffer) and specifically asked if we would extend our contracts the third year to help start another new town down by the Omo River. Initially, we had mixed feelings about the idea, anxious to get home and start the rest of our lives, but we came to realize that what we were already doing in Ethiopia would forever be a fundamental part of anything that came afterward in our lives, so why not stay.

In your book, there is really no mention of the Peace Corps staff. Did you have any contact with them? I say that because when I was the APCD in Ethiopia from ’65–’67, I was responsible for about 100 Vols on the Gondar and Dessie Roads. I saw them all once a month. I usually spent about 26 days a month driving from town to town, up the Dessie Road and down the Gondar.

We were probably visited by Peace Corps staff three or four times during our first two years in the southern Rift Valley. The last visit I think included the Country Director and several Ethiopian officials in a small parade of 4WD vehicles after I’d written a rather lengthy account to the Peace Corps staff about what we’d been doing.

Helen & Ted outside their home in Menze Seller

Part of the reason for the lack of site visits by the Peace Corps staff was because our village was cut off from the outside world for months at a time by the two annual rainy seasons. The track to our village from Arba Mench, the nearest real town, simply became impassible, even on foot. It wasn’t just the mud. There were two large, fast-flowing rivers that stopped even the most determined traveler.

Another reason was because we came out of our village by truck or friendly 4WD vehicle at least once every few months to get shots or other medical treatments up in Addis, and to buy boxes of food staples and batteries. This gave us the opportunity to catch up with our Peace Corps bosses, David Levine and later Jack Hjelt. They enticed us to visit by allowing us to tape their latest music, which we would then play in our hut to remind us of the outside world. Our trips north also gave us the chance to beg free “sample” medicines from pharmaceutical companies for the village clinic we had helped set up.

I don’t remember any Peace Corps staff visiting us during our third year on the Omo River, but we didn’t expect any given the extreme remoteness of our site. Driving there from Addis in a 4WD vehicle would have taken staff at least two weeks to get in and out in the best of times, or driving in from the closest Ethiopian Airport (Jinka) would have taken at least a week round trip.

I’m sure stories of your tour came up at the dining room table when your kids were young. Did any of them join the Peace Corps because they were influenced by the stories you told of your adventures?

One of the most important benefits of our US Peace Corps experience was gaining an awareness of the rest of the world. We both had grown up in America in relative privilege and had somehow come to believe that this was our American “right.”

Our volunteer experience in Ethiopia taught us that while Americans are unique, intelligent, and deserving in many ways, so too are most people in the world. Nearly all of the people we worked with on a daily basis had never been to school, but even among people who couldn’t read or write we found many who were much more intelligent and deserving than we were.

It was a very unexpected, eye-opening lesson that later helped us move our young family to New Zealand in the 1970s, sight unseen, in search of a government with less of a corporate conscience and more of a social conscience. Our two children did learn about their parents’ Peace Corps experiences and their views of the world, but not really through our stories. They learned simply by growing up in New Zealand, visiting American relatives for lengthy periods of time and playing with the large collection of rural Ethiopian artifacts scattered around our house, like woven grass jugs, hand-hewn stools, Coptic Christian crosses, unusual musical instruments, six-meter snake skins and a very extensive collection of photographs.

New Zealand does have a program equivalent to the Peace Corps called “Volunteer Service Abroad” or VSA, but our children ultimately chose to follow slightly different paths. One ended up in Korea as a cognitive scientist with a Doctorate in Philosophy fluent in Korean, teaching at Kookmin University in Seoul. The other earned a master’s degree in fine arts, travelled extensively and now makes ephemeral artworks critical of unfettered capitalism.

Looking back, what did you learn from your Peace Corps years, and what — if anything — did you leave behind to help the country and individual Ethiopians?

As mentioned earlier, fifty years on there is now virtually nothing left of our work in Ethiopia. We initially had the feeling we were almost missionaries “bringing light to the heathen,” but soon realized it was just the opposite. It was us who were learning most from the Ethiopians we were trying to “help.”

The Derg killed Haile Selassie only a few years after we’d left the country, so for many years we were worried that a number of Ethiopians we knew had been killed. In our recent return there we heard some sad stories, and for various reasons we found almost no one we had known back then, still alive. But thankfully, we did find out that one of our closest Ethiopian friends, Afework Tadessa, (in the “End of the Road” story) is still alive. Although we never did manage to contact him, apparently he is now living near Addis Abeba and has children in Great Britain and America.

In this day and age, and based on your political ideology, would you suggest the U.S. continue the Peace Corps or just let it slip away?

I think the Peace Corps is one of the best things America has ever offered the world, apart from its initial ideas on democracy (now after two centuries and a bit under corporate threat, I think perhaps in need of a peaceful update).

While we were volunteers in Ethiopia there were also other volunteers there supported by the governments of Canada, Great Britain, France, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden and New Zealand, so the US Peace Corps probably wasn’t the first program in the world to provide enthusiastic, educated young people to help poorer countries improve themselves.

However, it certainly had, and hopefully continues to have, the largest and most important volunteer program of any modern country, which for over 60 years has provided a positive view of America to many people and governments around the world. It has also brought home to America, returning volunteers with a much more accurate, realistic global view of the world.

Unfortunately, the perception of some people outside the USA today is that America’s primary interest is not in “protecting democracy,” but in selling its armaments and capitalist ideology to anyone willing to buy them.

Helen and I sincerely hope that the US Government will not let its Peace Corps program disappear on the convenient excuse of the global Covid-19 pandemic. I believe it remains one of the most important, visible demonstrations of America’s interest in global peace and world prosperity of all its global outreach programs and “defense” grants that it currently offers other countries.

•

Ted thank you for documenting your experience as a peace corps volunteer in Ethiopia. Where did you do your Amharic language training? If it was in the Virgin Islands, I was one of the trainers and perhaps we may have met. I also worked as a language trainer for nurses and doctors in Gondar and Addis Ababa.

I believe in the basic concept of the Peace Corps program. I am now trying to get the government of Ethiopia to initiate a “Prosperity Corps Program” to help transform the lives of people in all villages in Ethiopia. Without the injection of new ideas and a catalytic force, prosperity will not hold. If you have the time and the will perhaps you can work with me. If you come to Ethiopia, you can stay at my house. I can be reached by email: samtad007@gmail.com.

Samuel Taddesse, Addis Ababa Peace Corps Staff from 1962-1968.

Dear Dr Samuel Taddesse, I think we may have met as Helen and I did do some of our Ethiopia X (10) training in the Virgin Islands in 1968. What a small world. I like your idea of a Prosperity Corps Program for Ethiopians and thank you for your offer of a place to stay if we ever returned. But it took us decades to organize our first (and only) trip back to Ethiopia and unless a miracle happens with my books we probably won’t ever be in a position to join your cause. I know words are of little comfort when you clearly need much more, but we both sincerely wish you well in your search for support.

Consensus is good if you have the time. However, most situations need urgent remedy. Is there a “near consensus” formula?

Dear Leo, actually there are a number of books on the subject. Have a look at Ted Rau’s book on Sociocracy among many others. Also, our current forms of Democracy actually use a form of consensus decision-making already, which most people don’t appreciate. Every time any democratic decision is made, at least half of the group involved must reach consensus on what they are voting for. Think of it. All of those involved in any majority vote in any democratic institution must first reach common agreement on what their vote will cover. If our politicians and the general public only recognized this, perhaps more people would be willing to try consensus decision-making when faced with a tough problem to solve. They may find, as I did in Samoa, reaching and then implementing a decision made by consensus can actually take less time to complete than a normal democratic decision because there is no opposition putting up roadblocks to stop its implementation.

These were great questions, and the answers were incandescent in their clarity and passion. Although I shared many similar experiences in Ethiopia (1962-64) and arrived at similar conclusions later in life, I know that our experiences were far from unique. As stories curator for the Museum of the Peace Corps experience, I’m privileged to read accounts from Peace Corps volunteers from many countries across three generations. At its heart, the Peace Corps is a transformative experience for volunteers and the people we serve. The world needs us now more than ever.

John, I absolutely agree with you.

Ted, a highlight for me in this thought-provoking interview (which requires several readings to digest it all) was your discussion of consensus-building, that participation, vs. majority rules, can lead to greater acceptance and better implementation of the result. I particularly appreciated your soul-searching comments upon returning to the site after 50 years and that “it was us who were learning most from the Ethiopians we we trying to help,” which is so often the case.

Thanks Steve, for you thoughts. Now we just have to convince the world of this, and more importantly, convince people that consensus could actually become the new normal. We’ve all grown up in the believe that our current democracies are perfect and cannot or should not be changed; and that consensus would never work in large groups anyway, particularly if they are dominated by narcissistic participants. I certainly do not agree with this, though I think any changes would need to be made in very small, peaceful increments, starting, perhaps, by simply convincing fellow club or committee members to try it out so people can see and appreciated some of its many positive benefits.

Thank you, Ted, for this thoughtful interview. You voiced the knowledge that many of us may have come to that “invisible” power can be, and usually is, misused whether intentional or not. Unfortunately, that invisible power is still not understood as it relates to racism in America and beyond. Before you complete the third edition of POWER, CHAOS and CONSENSUS, contact your closest Baha’i Assembly to learn how Baha’is are using “consensus decision making” to change social environments, local and worldwide. The principles are compatible with those you mentioned in your list. I wish I had understood them before I went to Ethiopia (1962-64). I look forward to reading both of your books.

Thanks Joyce, for your suggestion. Yes, I believe the “invisible” power of individuals and governments is a large contributor to the global problems we now face around this planet. A lot of my ideas on power have some “Baha’i” in them. One of my friends is Baha’i and my wife and I spent two years in Samoa working with consensus decision-making in their local villages, while living just down the hill from the wonderful Baha’i temple in Apia.

Thanks Ted

John and I were in Ethiopia 68-68.

We traveled down the Rift Valley…working in Maji and eventually to lake Turkana and across the border.

I love the house you built and the work you both did. I enjoyed the read of your article.

We return to our village Mettu by flying to Gambella often. Weren’t we all fortunate to make Ethiopia our second home.

Memories for a lifetime

Patti and John

Thanks Patricia. What memories for you too. For us, the Peace Corps experience came at the perfect time in our lives and has formed a major cornerstone of it ever since.

Thank you for your comments and invitation. My wife and I were Ethi III I believe and it changed our lives and our world view. It showed us the way to TOGETHER.

We are all ion this together and we need to learn from one another and help one another and love one another.

Keep on sending us down this path. . . TOGETHER.

Dan and Suki Crowley

617-877-7373

Dear Rev Daniel Crowley, Yes, I agree with your emphasis on “together”. It is why I believe consensus could and should be playing a much greater role in all our lives. It wouldn’t be hard to do if most people on this planet hadn’t already lost the art of consensus decision-making many millennia ago. Unfortunately, over the last two centuries in particular, we have been carefully taught to think that the best way to solve a problem democratically is to rubbish the suggestions of our opponents once we know we have a majority, rather than continue to carefully listen to them to see where there may be additional common ground. What inevitably happens is that the best options are turned into black and white choices, which unavoidably creates both winners and losers. We now seem to believe without question that we must use a form of decision-making that divides us rather than unites us. This approach suits the supposedly “free and unbiased” (but self centered) media because sharply different opinions sells news. As long as our press and our education systems continue to think we’ve reached the epitome of political evolution with our current democratic forms of government, I cannot imagine how we’ll ever find peace, much less social justice for all, on this planet.

Thanks for your vivid and poignant recollections. One thing I have found is that our time in Ethiopia was most notably impactful on our children. We brought them to Ethiopia 25 years after we left and they were amazed to see in person what we had been talking about all those years. Our older son had been born in Ethiopia and was about to go to Honduras as a PCV. It was an amazingly meaningful trip for us, made more so by the power on them.

It’s too hard to pin down impact or lasting influence, but nice to see it in one’s own family and hope that it also migrated to others.

Dear Phil. What great parents you are. We would have loved to have done the same (had we been smart enough to think of it), but we would never have managed to put it together back then. It was only after we met Sam Cunningham, who lives in Auckland, and found out he had grown up there (until his family was kicked out by the Derg) that we finally made the effort to go, using him and his in-country Ethiopian friend as very personal guides. It was an incredible 6 week trip for us, but a bit too late to have our remaining family join us.

Extremely interesting interview. What could be more hopeful and useful today, than consensus building. Thank you.

Does the artist in the family have a website? The description of the artwork is so intriguing.

Dear Cynthia, Thank you for your thoughts. Our artist son has many websites. The simplest one is on Wikipedia” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tao_Wells but just type in your browser “Tao Wells” and you’ll discover lots of his work.