“Moritz Thomsen: His Letters and His Legacy“ (Ecuador)

Moritz Thomsen: His Letters and His Legacy

by Mark D. Walker (Guatemala 1971-73)

First published: January 2020 edition of Scarlet Leaf Review

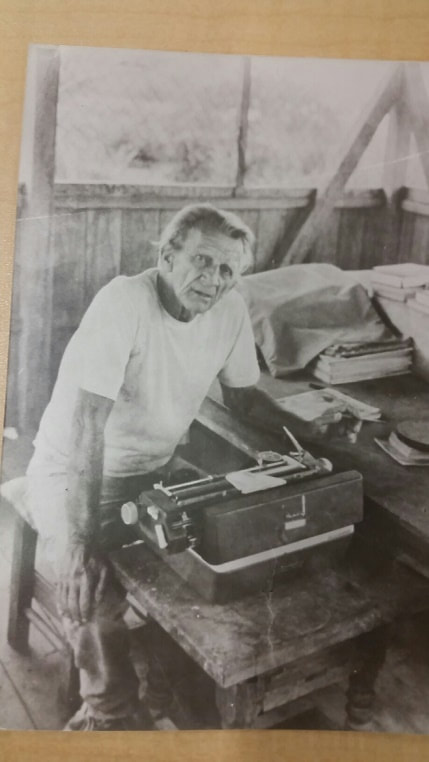

Moritz Thomsen was an extraordinary writer and influential expatriate who spent thirty years in Ecuador studying the culture and identifying with the people with whom he lived. Although Thomsen only wrote five books, which have been compared to the works of Thoreau and Conrad, he was an avid letter writer. His missives numbered in the multiple thousands, though according to one letter, he was only able to respond to five letters a day on his typewriter, often in the hot, humid jungle of Ecuador. And yet, despite his propensity for separating himself from the outside world—or perhaps because of his isolation—he corresponded with numerous authors, publishers, and professionals. Upon returning from one trip abroad he said he found close to 400 letters to answer. According to author Tom Miller, Thomsen was a “wicked” literary critic, “…the severity of one letter from him could often take days before its impact wore off.”

After rereading Thomsen’s best known work Living Poor recently, Paul Theroux, the “Godfather” of travel literature revealed,

A British publisher, Eland Press in London, is reissuing Moritz’s books—they just asked me if they could use my intro for nothing, and in the spirit of Moritz, I said yes. Actually I think Moritz would have had a big argument with them about money—his letters to publishers were fierce! Someday, someone has to sit down and gather all his letters and publish them in a big volume. His letters may prove to be his true masterpiece.

In another exchange, Theroux went on to say,

While the subject is riveting, and the details of peasant life vivid and unusual, Moritz himself did not really find a way to bring the people to life in “Living Poor.” His models were Hemingway and Thomas Wolfe and god-only-knows who else—big personalities. Moritz himself did not have the ego, or the style, to match them. I think his writing improved with “The Saddest Pleasure” and “The Farm…” (“The Farm on the River of Emeralds”) but in essence his writing has an epistolary feel—as though he is writing a letter to a reader; and is the reason his collected letters are probably his magnum opus. Just a thought.

Theroux met Thomsen in 1976 at a talk on “Aspects of the American Novel” sponsored by our State Department at the US embassy in Quito, and according to a letter Thomsen wrote fellow author Craig Storti, “It wasn’t particularly impressive, but he was such a nice guy that everyone forgave him. I tried to talk him into a PC (Peace Corps) novel, but the Peace Corps is not especially news at this point.”

They met again in 1977 when Theroux was writing The Old Patagonian Express, and according to Theroux,

It was Moritz who said to me one afternoon on a Quito street, “I don’t get it, Paul. How do you write a travel book if all you do is go to parties?”

“Write about the parties?” I said. But he was dead right and I was ashamed of myself. I vowed to take the train to Guayaquil the next day.

Over the years they would correspond and a friendship emerged, which Theroux revealed in his introduction to The Saddest Pleasure,

I should have declared my own interest at the outset—he is a friend of mine. I am glad he used a line of mine as a title for this book. Our friendship is, I suppose, characteristic of many he must enjoy. We met in Ecuador twice in the late seventies and have corresponded irregularly since. He goes on boasting of his ailing health, his failing fortunes, and his insignificance. For these reasons and many others, I am proud to know him. There are so few people in the world like him who are also good writers.

Acclaimed author Tom Miller, who would dedicate his last book in Thomsen’s memory, met Thomsen while researching The Panama Hat Trail in the early 1980s. In an article in the Washington Post he wrote:

I saw the chain-smoking Thomsen with some frequency and formed a deep friendship that continued in extensive correspondence. When I saw him last, he was living near the Esmeraldas River, his emphysema worsening, in what was, essentially, a tree house with a typewriter, books, a phonograph and classical records. We sensed it would be our last face-to-face visit, though neither of us said so.

Thomsen’s “wicked” critiques are also reflected in this letter to Miller in 1986, relating to an article Miller co-authored, “The Interstate Gourmet: Texas and the Southwest, a Restaurant Guide”:

Last night I read “The Interstate Gourmet,” the perfect oxymoron; so my idea of you is changed. You are not that sweet child I knew with your honed sensibilities…You are a kind of 3rd rate Caligula, chewing, dribbling, degenerate with your debased tastes, your incessant hunger, the food going in one end, an endless stream of shit shooting out the other. I think of Tom, I think of shit—tons of it spread thick enough across the desert to bring it into bloom…I don’t think writers should write about things that don’t engage their basic passions. —And of course, studying your book-book prose, maybe, god help you, you never have. But stop Tom, before it is too late; you will not be chevere [cool] at 300 pounds.

Miller described the critique as “amusing” and went on to state, “His vicious comments are often directed not at the writer but at the person or situation profiled. Anyway, I did not object to a word of his critique.” However, in another letter he admitted, “Thomsen maintained a wide correspondence; the severity of one letter from him would often take days before its impact wore off.”

The shared friendship and respect Miller and Theroux felt for Thomsen led to what they would call “Moritz Memories,” which Miller described as,

A tribute to a great American expatriate writer, in a century for which the term expat has little genuine meaning. Thomsen lived the word fully. We are convinced that he will be recognized as a significant 20th century figure for his life and his words. He was an uncompromising sceptic, difficult to know well, impossible to forget. And destined to be fully appreciated only posthumously. The book will be made up of a biography, essays by those who knew him well, his correspondence…some of his line drawings, photos of him and excerpts from his three published books.

I came across a ten-page version of this effort from February 1997, what Miller and Theroux referred to as the “Moritz Project,” which was to have been the last phase of the venture, to be completed by the middle of that year. The plan references some of the twenty-five key authors and publishers Thomsen corresponded with.

John Hay was one of those authors who wrote a short essay plus a prose poem about Thomsen called, “Moritz’s Dream.” John Brandi, a well-published small press poet, who carried on a “vigorous correspondence” with Thomsen wrote, “M’s writings were those of a master seer—direct and sizzling, full of enough passions, insight and rare detail to rock me off my seat.”

Philippe Garnier, a French journalist who was in Los Angeles for the publication Liberation, also wrote a short essay about Thomsen and eventually would be instrumental in getting Living Poor published in French. He was also asked by Miller to write an essay about Thomsen for the “Moritz Project,” which turned into an extensive article, “Maquis: Apercu, de un autre paysage American” an in-depth piece on various contemporary maverick American writers, which included an extensive section on Thomsen.

Stan Arnold, the editor of the features section of the San Francisco Chronicle which published stories from Thomsen that would become his first book, corresponded with Thomsen for many years. Of Thomsen he said, “I’ve only known two Christians in my life. He was one of them.”

Mary Ellen Fieweger, a translator, editor for a university press in Ecuador, an essayist and friend, was also asked to write an essay about Thomsen for the “Moritz Project,” (also known as “Moritz Memories) which she titled, “FAME ma non troppo.” Fieweger also lived in Ecuador and said this about her essay in a July 1996 letter to Miller,

Since you’re probably sitting up there in Tucson worrying about the screed (no doubt interminable) on Moritz I’m cranking out down here in Quito, I’m sending a draft to put your fears to rest. You will note that it’s within (just) the 5,000 word/20 page limit stipulated. You will also note that I’ve treated everybody with kid gloves. Well, sort of. But I haven’t gone after anybody with brass knuckles. Though a few academics, including one anthropologist, are presented in terms they might not think altogether flattering.

Miller felt Fieweger knew more about Thomsen than anyone although she was not easy to get along with, so Miller asked Theroux if he would take over future interactions with her. Theroux said of her, “Mary Ellen convinced me that she is a terrific resource and that Moritz was more B. Traven than I had really grasped,” which is another reason why Thomsen’s correspondence would become such an important window into his life despite having written four books about it. After Thomsen’s death, Fieweger would become the “Literary Executive” to negotiate for his estate.

The Origins of Tom Miller’s Collection of Moritz Thomsen Letters

In February 2018, Miller contacted the editor of Peace Corps Worldwide, a blog for Returned Peace Corps Volunteer authors looking for someone willing to complete the book about Thomsen and made these comments about how and why he came across so many of Thomsen’s letters:

One night more than 35 years ago I met Moritz Thomsen, a writer and former Peace Corps Volunteer. This took place in Quito, capital of Ecuador where Thomsen had served. His account of his Peace Corps years is wonderfully detailed in Living Poor, the first of a handful of terrific nonfiction books that earned the author ranking as among the best American expat authors of the twentieth century. I describe him like this: He was a man of almost insufferable integrity and undeniable charm.

Over the years until his death in 1991 Thomsen befriended many writers on the literary gringo trail through the Americas as well as Peace Corps officials, local farmers, and others, building up an impressive array of acquaintances with whom he corresponded. I count myself among them, all the more fortunate in that I came to know him personally. At one point late in the twentieth century I had in mind to write a biography of him, or at least, with Paul Theroux, compile a Festschrift (literary tribute) in his honor. Neither effort reached fruition. Still, I amassed an enormous amount of material about him going back to his military service as well as letters he had written to others.

As part of the “Moritz Project,” Miller had requested copies of Thomsen’s letters from all of the authors he knew had corresponded with Thomsen, and his best source was John and Ruth Valleau. (This material is available for review in the University of Arizona Special Collection).

According to Miller,

They came to my attention through an elderly woman in a retirement home in San Francisco who knew Moritz in college, who got in touch through her daughter who saw my announcement soliciting Moritz memories. She simply recalled a friend of Thomsen from college. She had enough of the name right and the city, that through the University of Oregon alumni office I was able to track down the Valleau’s.

JohnValleau was a college friend of Thomsen and shared a room. “Butch,” as Ruth called Thomsen, spent the Valleau’s wedding night in a cottage with the newlyweds, and according to Ruth,

We spent a happy and boozy evening, the three of us. And of course Moritz kissed the bride. His lips quivered as we kissed. They trembled each time I ever kissed him — then and through the ensuring years…I loved John but it was easy to be in love with Moritz, too — he was gorgeous, with incredible blue eyes and a smile that made me weak in the knees. He was witty, urbane, sensitive, and more than a little mysterious.

Thomsen referred to Ruth as “Panther Eyes” in his letters and after both “Butch” and “Panther Eyes” passed away, Ruth’s estate sent Miller several boxes of letters and sketches.

Other Literary Encounters

Thomsen told of his encounter with Eduardo Galeano, Uruguayan author of Open Veins of Latin American, in a letter to Miller in 1989:

Did I ever tell you I met Galeano in Quito at “Libri Mundi” [a bookstore Thomsen helped set up] [I]fell to my knees before him (almost) called him “maestro” [teacher] and gave him a copy of the “Farm” [on the River of Emeralds]. He was guarded by a mancha of “pistoleros,” Quito Marxists in black leather jackets who didn’t like to see Eduardo talking to a gringo.

Although Thomsen wrote some blistering critiques of books written by fellow authors he announced his first negative review to Miller in a June 1991 letter,

Got my first Vile and wicked review in 25 years—from the London Times. It is bitchy—and had I not written the book very similar to the review I might have written. All the English reviews are very good and…generous. Cogdon [his agent] says the River Esmeraldas book did not catch on.

Clay Morgan was a fellow author who corresponded extensively with Thomsen, and told Miller the following in a letter written in April 15, 1996,

I dedicated “Santiago” to Moritz. In fact, the “little blue man,” who appears on a rock in the middle of the river, is a humorous poke at Moritz. Moritz dedicates “The Saddest Pleasure” to my wife Barb and me.

I’m enclosing an essay I did for Writers Northwest, a couple of years back, so you can see if my perspective is one that will fit your book. [Miller also requested an essay about Thomsen for the “Moritz Project”] I have many letters—I think you may be mentioned in one or two—but haven’t pulled them out to look at them since his death. Mark Lowry, a professor from Western Kentucky University, has asked for letters, too.

Moritz Thomsen Versus Editors and Publishers

Thomsen had a rather contentious relationship with agents and publishers, although he managed to get his first three books published. Thomsen sent his stories of life in the Peace Corps on a regular basis to the San Francisco Chronicle, despite being told they weren’t interested. Evidently they reconsidered once they received the initial stories, which were eventually compiled into his best known work, Living Poor: A Peace Corps Chronicle, published by Washington University Press in 1969.

Page Stegner, a friend and fellow Peace Corps Volunteer and author, said of Thomsen:

[He]could rise to inspired heights of eloquence in his condemnation of all agents, editors and critics (whom he regarded as a kind of literary Gestapo) who maliciously failed to appreciate or understand his work. “Of course,” he would say, subsiding in his chair, “the bastards are probably right.”

Stegner would deliver the manuscript of Thomsen’s second book, The Farm on the River of Emeralds, to Don Cogdon, who would become Thomsen’s agent. When Cogdon asked for notes and asked when it would be done Thomsen sent back a 400-page manuscript with a curt note saying it would “end with a period.” The book would become the “poor orphan”of Houghton-Mifflin publishing company, since the two executives Thomsen had worked with left their positions for other companies. This dumfounded Cogdon, who stated that Thomsen, “had brought these people [in his book] to life in a Dickensian fashion, to be both colorful and memorable.”

Cogdon did convince Vintage, a division of Random House, to produce a paperback edition. In an interview with the publisher of Peace Corps Worldwide, John Coyne, Thomsen revealed his vision for The Saddest Pleasure, “A novel? On the inside cover of the last book about going to Brazil, I told my editor I wanted to say, after the title: travel book as memoir, memoir as novel, novel as polemic.” Several author friends leaned on the editors of Graywolf Press to publish this epic journey. According to Thomsen’s agent, Don Cogdon, he was able to “place British rights” where it received a better review as, “The British have greater interest in travel memoirs then readers in the U.S.” Thomsen’s second to last book, My Two Wars, was not published until five years after his death. He corresponded with Page Stegner about the book’s focus on his hatred of his father (one of the two wars), and Page urged him to focus more on his stories as a bombardier in the Second World War, as it resembled Catch-22 in its poignancy and hilarity.

Thomsen’s Legacy

In a letter to Tom Miller, Martha Gellhorn, considered one of the great war correspondents as well as being the third wife of Ernest Hemmingway, summed up Moritz’s decision to leave a life of privilege,

Moritz Thomsen rejected wealth and all its values, starting with his very rich father; he chose to live poor, as poverty is the majority human condition. He was true in practice to his beliefs and the result, for us, is truly extraordinary writing. I had never heard of Moritz Thomsen and by chance found “Living Poor.” I was electrified by something (not found) in any writing…I think he must have been a unique human being because the quality of his writing could not be separated from his spirit. His books should survive when many others, far better known, are forgotten.

In a similar vein, Paul Theroux said the following in a letter to Miller in July of 1993, “He was an exile, a refugee, a hostage—lots of incarnations. I often think that what he was and the ways he lived his life was as important as his writing.”

According to his fellow author and confidant, Mary Ellen Fieweger, “I think he was ready to die, and determined to do it the way he had chosen to live most of his adult life. He died poor, with a disease that affects only the poor.”

Thomsen was possessed with the thought of death for many years before he actually died. According to fellow author Mark Lowry II, Moritz grew more “absolute—his cynicism, advice, softer side, and crotchety morality all more pronounced. He wrote one friend, ‘I see now that death doesn’t arrive at a certain moment with a clang and clatter. It is simply a slow leak.’”

To another friend who was planning a visit Thomsen wrote,

I contemplate a visit from you in August with mixed emotions and wondering if I will still be alive. I’ve been talking like this for ten years and don’t die and have to apologize to my friends for lingering on. Lately, however, I don’t move around and figure seventy-five is OK. I can leave the party because it’s a f…ing drag when it takes thirty minutes to put on your socks…I think you have never lived as I live now, starving for human and intellectual contacts in complete isolation….Writing, the source of so much pain, I think I’ll give up. My gift to humanity—and myself…Yesterday I had more to tell you. Now, today, the mind has gone blank.

These, according to Lowry, were among his last words.

In August of 1991 (shortly before his death), Thomsen again wrote to Page Stegner, “Page, I am half sick and will write you again in a few days. Thanks again kid, I have put you through hell, but how else does one get ahead except walking on the backs of his betters.” In 1995, Stegner and several other friends convinced Steerforth Press in South Royalton, Vermont to publish My Two Wars after they tracked down Thomsen’s only heirs, a niece and nephew, for permission. And in 2018, Thomsen’s niece and Executive Literary Agent, Mary Ellen Fieweger would finally and independently publish his last manuscript, Bad News from a Black Coast.

According to Mark Lowry II’s, “The Last Days of Moritz Thomsen”, Esther (Ramon’s divorced wife) describes Thomsen’s last words,

Around 11:00 or 12:00 I woke to a loud thump. Don Martin was trying to get to the bed pan. The IV was in his way. He ripped it out and….”I don’t need this sh-t.” I pleaded, “Don Martin no! Please leave that alone. You need it. Let me help you.” But he said, “I can still do something. I can go to the bathroom myself.” I told him, “if you can’t, just say so, and I’ll hold the bed pan for you.” He said, “No. I still can do it. I can take care of myself.”

He died on August 28, 1991 at 11:00 P.M. dying as he lived most of his adult life, staying true to his values of living amongst the poor and rejecting comforts that his father had envisioned for him.

After reading hundreds of Thomsen’s thousands of letters, I’ve learned many things about the man not revealed as intimately in his books. His letters offered an opportunity to share some of his most inner feelings and fears with people he trusted and respected and considered part of his literary family. He wrote to some of these authors for over twenty years. His letters like his books were transparent but possibly rawer and obviously unedited. They included and abundance of colorful and profane language and a good deal of irony and humor was sprinkled throughout his correspondence. He offered good advice about writing and life which is one of the reasons so many authors continued the dialogue with him, sending countless letters on their long and often endless journey into the jungles of Ecuador.

Although I didn’t know Thomsen and never corresponded with him, he’s the author I consider my “literary patron saint”. His transparency and lifelong commitment to live among and try to understand some of the most abandoned people in Ecuador, the different ways he described what he saw and the impact it had on countless writers is an inspiration and something worth emulating.

•

Mark Walker (Guatemala 1971-73) has published in Ragazine, Literary Yard, Literary Travelers, Quail Bell, World View and Revue Magazines. “Hugs not Walls, Returning the Children” was an essay winner for the “Arizona Authors Association” 2020 Annual Literary Awards. In conjunction with several RPCVs, he’s producing a documentary, “Guatemala: Trouble in the Highlands”. His wife and three children were born in Guatemala. He is the author of the Peace Corps memoir: Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond. You can learn more at www.MillionMileWalker.com

Mark Walker (Guatemala 1971-73) has published in Ragazine, Literary Yard, Literary Travelers, Quail Bell, World View and Revue Magazines. “Hugs not Walls, Returning the Children” was an essay winner for the “Arizona Authors Association” 2020 Annual Literary Awards. In conjunction with several RPCVs, he’s producing a documentary, “Guatemala: Trouble in the Highlands”. His wife and three children were born in Guatemala. He is the author of the Peace Corps memoir: Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond. You can learn more at www.MillionMileWalker.com

What a wonderful essay about this amazing man.

Thanks Dick! Here’s what another RPCV said about it:

Jeff Hopkins — “Thanks brought this fantastic story of cross-cultural understanding and friendship with me to Guatemala in 1987. Read it once but could tell you the entire plot today. I should read his other works thank you!”

I look forward to hearing more stories from other RPCV’s about the impact of one of the best RPCV authors.

Also, in the spirit of broadening the base of readers beyond RPCV publications, I’d suggest doing a “Like” at the end of the version in the Scarlet Leaf Review: https://www.scarletleafreview.com/non-fiction2/category/mark-d-walker

I’m working on a fourth in the series of articles about Moritz and will target literary journals and platforms to give a higher profile of Moritz and having a good showing in “Scarlet Leaf Review” will enhance that possibility.

Cheers,

Mark

Well done, Mark. Congratulations.

Lorenzo–Gracias! It’s so nice to find a talented RPCV author to learn and write about. The next article will be the most revealing though…

Moritz, I hardly knew ye. Now I find your isolated life was shared with multitudes. Luckily Mark and his contacts are assuring your story will survive.

Thanks Sheila–I’m putting final touches on the next article on Moritz–and his relationship with Ramon–I’ll share it once it’s published. Thanks again for sharing your letters from Moritz.

Thank you, Mark Walker for your essay on Moritz Thomsen. I was a PC volunteer in Ecuador 1967-70 and nearly became an expat as a few PCV’s did. I met Moritz a few times but never got to know him well as several others you mention and quote did. I certainly knew of him and greatly admired him back in the day and since precisely for the set of values that he wrote about and lived.He among very few of us Western voracious consumers stood up against the current that carries us along to what we know will end badly. Thanks again

My pleasure Mike. I’m writing “the Moritz Thomsen Reader: His Books, His Letters and His Legacy by the Writers Who Knew Him Best.” I have a proposal and am looking for a publishers. You’ll love it! Mark

Mike–one more thing. I’ve been interacting with Professor Michael Handelsman about Moritz–he brings additional insights about the author–a very complex writer for sure. I’m presently working on my next article on Moritz, “The Strangest Pleasure: A Journey of Two Writers.” Cheers, Mark

[…] Upon returning from one trip abroad, he said he had found close to 400 letters to answer. According to author Tom Miller, Thomsen was a “wicked” literary critic, “…the severity of one letter from him could often take days before its impact wore off.” Here’s the link to my description of his missives: “Moritz Thomsen: His Letters and His Legacy“ (Ecuador) – Peace Corps Worldwide […]