“Disillusionment in the Delta” by William Seraile (Ethiopia)

After his Peace Corps service in Ethiopia, William Seraile returned home to earn his masters in ’67 from the Teachers College at Columbia, and a doctorate in American history from the City University of New York in 1977. Now a professor emeritus — after 36 years teaching African American history at Lehman College, CUNY in the Bronx — Bill lives in New York, and is the father of two and grandfather of four.

In a 3-part review published on this site in 2016 of The Fortunate Few: IVS Volunteers from Asia to the Andes written by Thierry J. Sagnier (2015), I wrote about Seraile and other RPCVs (33) and Peace Corps Staff (15) who joined the International Voluntary Services (IVS) and went to Vietnam, and I wrote about the four IVS veterans who went from IVS into the Peace Corps. What follows is Bill Seraile’s account of his Vietnam experience. — JC

•

Disillusionment in the Delta

by William Seraile

William Seraile (center) meets Haile Selassie (right)

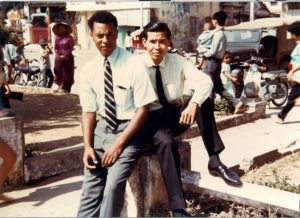

I am originally from Seattle, but was living in New York when I joined IVS. After earning a B.A from Central Washington State College (now Central Washington University), I entered the Peace Corps as a social science teacher in Mekelle, Ethiopia (1963-65) That experience whetted my appetite for overseas adventures which is the reason why I went to Vietnam in October 1967. Ivan Myers (deceased) was for a time my housemate in Ethiopia and he was the one who told me about IVS. To Ivan’s and my surprise, we arrived at orientation in Washington, D.C., to find Gary Daves who also served in the same Ethiopian town. What a coincidence: three former PCVs from the same small Ethiopian town going off to Vietnam. (Gary was kidnapped in Hue following the Tet invasion and spent five years as a POW until 1973).

My service in Can Tho was from October 1967 to late April 1968. I was age 26 when I arrived. I taught English at Phan Than Gian high school with a schedule that resembled a college professor’s light teaching load. Additionally, I was engaged in language instruction. The school, with 3000 students, was formerly a French fort and a WW II Japanese barracks. As the only American on the faculty, my classes were very large.

Before Tet, I became disillusioned teaching English because I thought that I could better serve the country by working in a refugee camp. These feelings were so strong that I informed IVS Saigon that it was not right for me to teach students who were using their acquired language skill to quit school and work for the U.S. military or for USAID. My threats to resign at the end of the school year unless I was given a transfer was never replied to by IVS.

Unfortunately, the Tet Offensive of January 31, 1968, curtailed my teaching as the school became a refugee center until mid-April. Jerry Kliewer, Roger Hintze, John Balaban and myself volunteered to assist American Air Force doctors and nurses in the local hospital as they were overwhelmed with civilian victims of the war. They quickly trained me as a scrubber in the operating ward where I cleaned wounds prior to surgery. Consequently, I witnessed surgeries of all types including amputations. This was my volunteer assignment for about six weeks (with a short leave to Saigon) until the number of wounded patients returned to “normal.”

The horrific conditions of civilians caused John Balaban (who had resigned) to return to Vietnam to work with the Committee of Responsibility to help send severely injured patients to American hospitals. In this capacity, John learned to speak fluent Vietnamese and, later, to translate Vietnamese poetry into English. He also established the Vietnamese Nom Preservation Foundation (I am a board member) to preserve by digitizing the ancient language.

After all these years, I harbor some regrets for leaving Vietnam before completing my assignment. But there were mitigating factors.

After all these years, I harbor some regrets for leaving Vietnam before completing my assignment. But there were mitigating factors.

David Gitelson, whom I met once in Can Tho, was murdered on January 26, 1968. The IVS volunteers believed that he was killed by the South Vietnamese army because he had information that an air strike had killed thirty-three civilians and that the government was involved in corruption involving a refugee program. He was well known in the Mekong Delta for his saintly demeanor and the Viet Cong had no reason to kill him. Gitelson was very humble. I had to chew out a military policeman who was criticizing David for wearing sandals. I told the soldier to get on the case of drunken American soldiers. Gitelson just kept quiet and acted meekly. He was known as the “poor American” for his sloppy and unkempt dress. A meeting scheduled (January 12, 1968) between Senator Ted Kennedy, Gitelson, Hintze, Balaban, Kliewer, Roger Montgomery and myself was abruptly canceled when a person(s) blew up our Jeep parked in front of Montgomery’s residence. We all rushed out and Hintze jumped into our Land Rover to take injured Vietnamese to the hospital, but quickly jumped out when a Vietnamese shouted “NO!” A dog walked too close to the right front tire and the vehicle was blown up by a mine (I had sat in the passenger side thirty minutes earlier).

Until today, I don’t know how mines or explosives were placed at the vehicles because about twenty Vietnamese were outside watching a television perched on a tree branch that was between the two vehicles. They had to have seen the intruder(s) but they were just as shocked as we were when the explosions happened. A few days later, an explosive was discovered outside my school. Was it meant to me? Overly cautious, I checked my scooter for stray wires before kick starting it.

Anyway, IVS offered all volunteers to leave by April 25, 1968, at IVS expense, or, if we remained, we would have to finish our assignment or pay our way home if we left before our contracts expired.

Earlier, on February 11, I wrote to my family and friends, “at this point, one must seriously question his motives for even wanting to remain in Vietnam. As a witness to this war, I sincerely hope that the Administration is providing the American people with the truth.” I decided to leave. My rationalization was that I had spent two years in Ethiopia where the conditions were more primitive than Vietnam and I did not have to prove to myself that I could survive in a third world country. (I had dysentery in Ethiopia and caught in time the beginning stage of trachoma). Besides, I was shot at twice during the Tet invasion and couldn’t see who was shooting even though it was daylight. Once, a few weeks after the invasion, I was in town when I witnessed a blindfolded man being shoved into a lamp post. I glanced to my left and on a balcony were two men with weapons and I thought that I was going to die. Fortunately for me, they were the “good” guys.

My final reflections about Vietnam

The war was surreal. Seeking safety in Saigon, I flew on Air America (a CIA aircraft) February 6 and approaching Ton Son Nhut airport, I saw in Cholon, the Chinese section, explosions and gunfire of an intense battle, yet to the left of the descending airplane I witnessed a military base (about a mile from Cholon) where half-naked American soldiers were playing a fierce basketball game. For a few days I “lost” all my Vietnamese language skills. Upon returning to New York and telling some friends about Vietnam, I mentioned that an IVSer heard that a guilt-ridden soldier confessed about a platoon massacring civilians. One guest responded angrily that “Americans don’t kill innocent people.” He pompously added that the “American press would have reported it immediately if it were true.” Later, the world learned about Lt. William Calley and the massacre at My Lai on March 16, 1968, but My Lai was just the best known of similar American committed atrocities. I really enjoyed living in Vietnam before Tet because the war was not a danger in the cities. Ironically, the night before the Tet invasion, I told Balaban that I might remain for three years, instead of two because it was so peaceful due to the truce to celebrate Tet. Luckily for me, I walked home a mere hour before North Vietnamese soldiers and their VC allies came en masse past my home.

Compared to my Peace Corps experience, I believe that Peace Corps did a much better job of selecting Volunteers. I never understood why IVS selected a recent widow whose husband had been killed in Vietnam. You would think that they would have had scrutinized her motives more carefully. Probably, they selected her because volunteers were resigning as a protest against the war.

My life after Vietnam

I visited the Vietnam Memorial in our nation’s capital searching for the name of a soldier whom I had met in 1967. In our conversation about the wisdom of the war, we argued about the purpose of the war. I pointedly asked him if he was willing to die for Vietnam. After a very long pause, he replied “No!” I could not remember his name, but his face and stocky built is easily recalled nearly fifty years later. I shed tears for him because I could not express sorrow over his demise, and I cried for Martin Luther King whose death did not resonate an emotion from me in Vietnam where death, violent deaths were the norm. I cried for saintly Gitelson who like all the volunteers came to Vietnam to do good and finally, I cried for myself, a returned Peace Corps Volunteer hoping to find in Asia another similar Peace Corps experience but disillusioned by a senseless war with its false body counts and light at the end of the tunnel mentality.

Contrary to Balaban’s belief that I would become a medical doctor (he thought that I enjoyed watching surgery)¸I earned a Ph. D In American History and taught African American history at Lehman College, City University of New York from 1971 to 2007. In many ways, Vietnam has been missed. Ironically, I was in Cambodia shortly after leaving the country and was struck at how calm and peaceful it was. My thoughts were this is what Vietnam should be like (unknowingly, Cambodia’s hell was soon to come).

Some times, when I think of Vietnam, I visit New York’s Chinatown to capture again the smells and sounds of Asia. My home is decorated with several wooden and stone Buddhas and other Asian artifacts. Recently, I provided information for those who are negotiating to send Peace Corps Volunteers to Vietnam. I mentioned that Vietnamese do not hate Americans for what they refer to as the American War. In fact, they believe that the war was a misunderstanding, and the two Bills — Clinton and Gates are very popular among the youth. I have yet to return to Vietnam, but Balaban, who goes several times yearly in conjunction with his foundation’s work, insists that I go. Someday, maybe I will.

Thank you,

I was a student at Phan Thanh Gian high school in Cantho from 1963 to 1970 but not recall that our school has had a foreign teacher who taught English. The school did not become a refugee center either as I went back to school a few weeks after the Tet offensive and helped the nearby estate to be destroyed by the VC at the weekend with our teachers.

I do not know why nor understand why Mr. Nguyen questioned my experienced in Can Tho. The school was a refugee center and was still not opened for classes when I informed the headmaster sometime in April 1968 that I was leaving the country. I was 27 then and maybe Mr. Nguyen being a young person might have witnessed another refugee issue at the school at a later date. I am upset that he has tried to malign my character.

I’m proud of you and your works, uncle Bill…

Bill thank you for sharing this moving and very personal story. Our country seems to have developed amnesia re Viet Nam and our misguided involvement there. Your shared memories bring it back to life.

Thanks for this, Bill. You can visit my effort to set IVS in Vietnam within US policy in Why the North Won the Vietnam War, in page 161-2, 170, 178-9, 191.

Please e-mail me for the book. I went to school with David Gitelson’s brother Mark, who was very much like David.

In the 1990s, while writing a history of the anti-war movement at my high school for The Vietnam War on Campus, I came across a school newspaper article David’s death .

As as you will see from that book, tthe paper’s editor painted that death in terms of his being a true anti-communist hero!

It was that which led me to take on creating an oral histories of IVS workers that eventually led Paul Rodell and I to conduct over 100 interviews.

Marc Jason Gilbert

mgilberft@hpu.edu