Paul Theroux in The NY Times (Malawi)

Pardon the American Taliban

By PAUL THEROUX

NY Times, OCT. 22, 2016

In the mid-1960s a young American teacher in a small central African country became involved with a group of political rebels — former government ministers mostly — who had been active in the struggle for independence. They had fallen out with the authoritarian prime minister, objecting to his dictatorial style. The country was newly independent, hardly a year old. The men advocated democratic elections and feared that the prime minister would declare himself leader for life in a one-party state.

Fluent in the local language, obscure because he was a teacher in a bush school, and easily able to travel in and out of the country on his United States passport, the American performed various favors for the rebels, small rescues for their families, money transfers, and in one effort drove a car over 2,000 miles on back roads to Uganda to deliver the vehicle to one of the dissidents in exile. On that visit he was asked to bring a message back to the country. He did so, without understanding its implications. It was a cryptic order to activate a plot to assassinate the intransigent prime minister.

Within months the plot was set in motion, but it was quickly foiled, all of the intended assassins captured and hanged; other suspects were arrested, imprisoned and tortured. The American was threatened with detention, then expelled from the country as an undesirable alien and prohibited immigrant.

I was that American. I was 24. The country was Malawi, the prime minister, Hastings Kamuzu Banda. My expulsion meant that I was kicked out of the Peace Corps (“early termination”), heavily fined by it for engaging in covert political activity (“unsatisfactory service”) and compelled to undergo an extensive interrogation (“debriefing”) at the State Department. This interrogation took place in the Bureau of African Affairs, where the scowling Jesse MacKnight scolded me before a roomful of bureaucrats, and then rather touchingly softened his tone and implored me to give him details about the underground rebel movement in Malawi.

I explained that the country was badly governed, and I felt the rebels would have provided wiser leadership and free elections. Mr. MacKnight reminded me of the assassination plot. It was obvious to the State Department, and to me, that I was in way over my head.

Within a few weeks I was back in Africa, in Uganda, with a teaching position at Makerere University, as a reward from the exiled Malawians there for my having played a part in their cause. In the event, Mr. Banda ruled Malawi for three decades longer and died peacefully at the age of 99.

I was a failure, and I was lucky in my escape. Over this past summer I read Michael Korda’s “Hero,” his excellent biography of T. E. Lawrence. Mr. Korda writes that Lawrence’s verdict for his efforts, his risk, his idealism, was that he’d failed, and that his subtitling “Seven Pillars of Wisdom” “A Triumph” was self-mockery. But “Seven Pillars” (to me a masterpiece) shows how Lawrence is a classic example of self-radicalization.

You become radicalized when you think that the world has ceased to care, and that in joining a shadowy band of zealots you might make a difference. Consider the Boston Irish who with “Noraid” helped fund the Irish Republican Army, which bombed innocent civilians in Ulster and elsewhere in Britain in the 1970s and ’80s. Or the young American Jews wishing to attach themselves to a cause, becoming passionate Zionists, going to Israel to patrol the West Bank as the so-called hilltop youth (No’ar HaGva’ot),brandishing Uzis, building illegal settlements and terrorizing Palestinians. Emboldened by his faith, Mayor Rahm Emanuel of Chicago served as a civilian volunteer in 1991 not in the United States Army, but in the Israel Defense Forces.

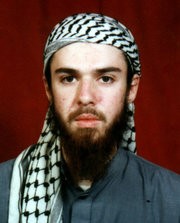

John Walker Lindh, in a photo taken while he was studying at a madrasa in Pakistan, before he joined the Afghan Army in 2001.

It was faith that induced John Walker Lindh to travel to the Islamic world. A Californian, raised as a Catholic, he converted to Islam at age 16. A year later he studied Arabic and Islam in Yemen, and subsequently, still a teenager, he relocated to Pakistan, where he studied at a madrasa. In the spring of 2001, stimulated by his faith, he volunteered for the Afghan Army. As his father, Frank Lindh, explained in The Nation in 2014: “John’s motivation was based on youthful idealism: He felt it was his religious duty to help defend civilians against Russian-backed warlords, the so-called Northern Alliance, which was seeking to displace the Taliban government. He was deeply moved by stories of horrific human rights abuses by the Northern Alliance.”

It was almost unimaginable then that the United States would declare Afghanistan an enemy. The George W. Bush administration, far from antagonistic, provided the country, which was led by the Taliban, with a $43 million grant in support of an opium growing ban in May 2001. Mr. Lindh was a foot soldier fighting the Northern Alliance when, after Sept. 11, the United States invaded Afghanistan on a punitive mission. Baffled by this turn of fortune’s wheel, Mr. Lindh fled on foot to Kunduz, was taken prisoner by the Northern Alliance, imprisoned and interrogated, and suffered severe physical harm. He was still only 20 years old when he was handed over to the United States military.

Ultimately remorseful, he accepted a plea agreement at a hearing in Alexandria, Va., in 2002, was sentenced to 20 years and is now in a federal penitentiary. He has been brutalized in prison; he spends his time studying and trying to avoid the attacks of his fellow prisoners.

His mission — like mine, like the volunteer Sinn Feiner and the ultra-Zionist — was to be useful, taking risks to help people perceived as oppressed; and like me, he did not fully understand the bigger picture, was in over his head, and was overtaken by events.

Hillary Clinton called Mr. Lindh a traitor on national television. I think that far from being traitorous, the idealism of Mr. Lindh is deep in the American grain.

A traitor, to my mind, would be someone Mrs. Clinton might be more familiar with, such as the international commodities trader Marc Rich, who defied American sanctions on Iran during the 1979 hostage crisis, making secret deals with the ayatollah, buying and selling oil on the world market and becoming a blood-money billionaire. He was wanted for income-tax evasion, wire fraud and racketeering as a fugitive by the F.B.I. But, in 2001, President Bill Clinton, whose library had received considerable funds from Mr. Rich’s ex-wife, Denise Rich, pressured by Israel, where Marc Rich was regarded as a patriot and benefactor, pardoned him on his last day in office.

“The supreme manifestation of power is the granting of a pardon at the last moment,” Elias Canetti writes in “Crowds and Power.” This puts the Clinton pardon of Mr. Rich in perspective. “A pardon has the appearance of new life.”

Dubious figures are not unknown as guests in President Obama’s White House. He has welcomed moralizing mountebanks like Al Sharpton — who along with his for-profit business was found in 2014 to owe more than $4.5 million in taxes — sententious celebrities and movie stars, and rappers with a history of violence. Clearly, President Obama is a forgiving man.

With that in mind, those of us who have been no nearer to this White House than a picket line would appreciate it if the president, in his last months in office, reviewed the case of John Walker Lindh with a view to commuting his sentence on compassionate grounds.

Paul Theroux is a great writer and this message is a great example of how a Peace Corps volunteer’s experience provides a unique worldview and perspective which last a lifetime. During this period of fear of terrorism Theroux’s view is by now means “politically correct” but it is well taken.

Another beautifully told story by Paul Thoreau! And a compelling appeal on behalf of Mr. Lindh. I would sign a petition to the President to promote such a pardon or commutation. Would that life were so simple that your last act was that by which you were always judged.