A Writer Writes: Folwell Dunbar (Ecuador 1989-92) Fear and Loathing on the Inca Trail

A Writer Writes

•

Fear and Loathing on the Inca Trail

by Folwell Dunbar (Ecuador 1989-92)

After all these years I still have flashbacks. When I see a child blindly strike a piñata or when I smell a rotten egg, the memory, lodged deep in my scarred bowels explodes to the surface. Like Marlon Brando in the heart of darkness, I recall, “The horror, the horror.”

“¡Levántate Leonardito! ¡Vamos!” the campesino or farmer yelled from the base of the hill. “Get up little Leonardo! Let’s go!”

Like grilled cheese, I was pressed between a lumpy straw mattress and a stack of cheap coarse blankets. I didn’t want to levántate; I was warm and reasonably content. I pretended not to hear. Moments later though, the campesino pounded on my front door causing chards of adobe to cascade down on my head. “Deme un ratito,” I pleaded. “Give me a second. I’ll be ready en seguida.”*

The weather in the high equatorial Andes is strangely unpredictable. The sun, so close to the earth you can almost touch it, burns like a glass blowing furnace. When it’s out, your skin blisters and you have to squint like Clint Eastwood in a spaghetti western. Cover it with a cloud though, and you’ll quickly need crampons and an ice axe. Latitude and elevation are always at odds. Because of this, dressing for a trek along the Inca Trail,** especially on a Peace Corps budget, was extremely challenging. I threw on lots and lots of layers; filled a backpack with reinforcements, including gear for rain, hail and brimstone; stuffed my feet into cheap, Chinese-made rubber boots,*** the traditional footwear of Ecuador; and then, regrettably, left the shelter of my humble abode.

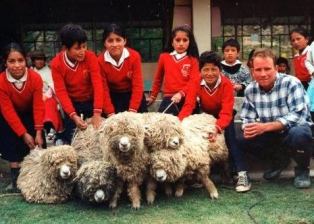

I had promised the campesino I would visit his farm. He raised sheep and alpaca, but was looking to diversify his stock. He wanted to channel water from an irrigation ditch into an earthen pond and stock it with trucha de arco iris, rainbow trout. I had started a couple of fish projects downriver and owned a water quality test kit and a thermometer, which, in the Parroquia of Jima, made me an expert on aquaculture.

We walked along a narrow ridge just above the Rio Moya. The higher we climbed, the smaller and fewer the trees. Eventually, there would be nothing but dry grass or paja. Author’s note: the lack of trees figures prominently in my PTSD haunted memories.

About thirty minutes into the two and a half hour hike, I released a rather inconspicuous burp. Unfortunately, it carried with it the unmistakable scent of sulfur, a telltale sign of giardiasis. Ordinarily, I would have simply popped a few Flagyl**** and soldiered on; but, in my haste, (see “ready en seguida”) I hadn’t packed the Roundup-like super drug. So, instead, I turned to my compañero and begged, “Amigo, is there any chance we could do this another day? No me siento bien. I don’t feel well.”

“Oh Leonardo,” he implored, “we’re so close. Por favor, es muy importante.” I thought to myself, “We weren’t exactly close and it wasn’t all that important.” He then pulled out a rusty flask containing his own home-distilled super drug, aguardiente. He handed me a shot and toasted, ironically, to health, “¡Salud!”

I winced down the kerosene-like concoction hoping it might at least momentarily appease the angry parasites in my gut, and continued along the winding path. It was at that time, between belches, that I had a jarring revelation, a “revelation” that should have been included in some Peace Corps pre-service manual. I noticed that the irrigation ditch, diverted from and channeled above the Rio Moya, flowed below acres and acres of pastureland used by campesinos to graze cattle, sheep, goats and other livestock. It was this same irrigation ditch that supplied my humble abode with agua potable or drinking water. “Hmmmm,” I thought, “that agua is probably not all that potable after all?”

And then, not unexpectedly, there was a second, larger and more pungent sulfuric belch. It was followed by a slow eruption of saliva, another telltale sign of impending doom. I called out to the farmer, “Amigo, me siento muy, muy mal. I feel awful. I have to return!”

Before he could offer me another well-intended shot of firewater, he actually recognized my dire situation. He saw the beads of sweat welling up on my exposed skin, skin that was now bone white and ice cold. He also heard the desperation in my cracking voice. He knew better than to push on. He said, “Leonardito, no hay problema. Perhaps we could do it another day?” He tipped his hat as though at a funeral and walked ahead.

I spun around and took several shaky steps in the opposite direction. I wanted to get away; I wanted to hide. I looked up and down for shelter. A Pot-O-Gold portalet would have been ideal, though I would have happily settled for a tree – My kingdom for a tree! Unfortunately, there was nothing but paja, miles and miles of knee-high paja. At that point, like an exhausted gazelle in the Serengeti surrounded by lions, hyenas and vultures, I simply stopped and waited for nature to take its grisly course…

They say the male human body has six major orifices: eyes, ears, nose, mouth, anus and urethra. All six of mine, along with thousands and thousands of pores, simultaneously erupted.

Stuff, gallons of stuff my body obviously didn’t want, sailed helter-skelter in all directions. I had control over nothing. My layers of cotton and wool absorbed as much as they could with the less viscous excess rolling down my flanks. Like clogged gutters in a toxic storm, my rubber boots, those damn rubber boots, filled to the brim and then overflowed. My backpack, worthless and forlorn, simply hung on for the ride. From afar, I must have looked like a clay pigeon struck by multiple shells. Up close, I looked and smelled like death.

I vaguely remember seeing the campesino glance over his shoulder, cringe, and then pick up his pace. I also noted that the cows and sheep on the hill coughed up extra cud in disgust.

Slogging my way back down the Rio Moya, filled with fear and loathing on the Inca Trail, I muttered, “The horror, the horror.” *****

•

Folwell served in Ecuador from 1989 to 1992. He raised rainbow trout in earthen ponds, tended sheep from Australia and New Zealand, and kept “killer” bees and cuyes (guinea pigs). A graduate of Duke and Tulane, he is a former teacher, coach and principal, professional developer, school evaluator and change agent. He is currently an educational consultant, writer and artist in New Orleans. He, his wife and their giant schnauzer, live downriver and on the wrong side of the tracks, two blocks from Desire (of Streetcar fame), a levee away from the Mississippi, and a short stagger from the Vieux Carré.]

Folwell “Leonardo” Dunbar is an educator, artist and Peace Corps survivor. He can be reached at fldunbar@me.com

•

* In Ecuador nothing happens quickly or “en seguida.” “Ya mismo,” sometime between now and the next zombie apocalypse, is more the norm.

** This was not actually part of the famous Inca Trail. Apparently, even the ancients avoided this route.

*** Even though they make plenty of sense in South Louisiana where I’m from (see Cajun attire), I refuse to wear rubber boots to this day.

**** Like Drano, Flagyl is fairly toxic. It’s supposed to be taken sparingly in regimented doses. For over two years I popped them like Gummy Bears. I also didn’t wear sunscreen, trekked up and down the Andes in cheap rubber boots, and drank way too much aguardiente. Like drinking water from an open irrigation ditch, I’m pretty sure these other youthful indiscretions are going to come back to haunt me as well.

***** Besides being hot, irritable, sliced up with a machete and totally insane, Colonel Walter E. Kurtz in Apocalypse Now probably suffered from dysentery.

!Pobrecito! I’ve been there. While stationed in Ica, Peru after the devastating 1963 flood, I suffered from giardia and shigella parasites. Our young, inexperienced, and traveling P.C. doctor assured me “it” was just nervous diarrhea. Months later, and pounds lighter, the parasites were identified and eradicated just in time for my return to the States after the completion of my term.