And You Think You Get Bad Reviews!

September 16, 2013

Gazing Into Their Past Through Their Bellybuttons

By MICHIKO KAKUTANI

SUBTLE BODIES

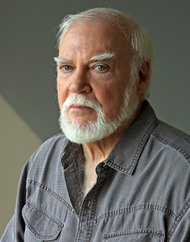

By Norman Rush

236 pages. Alfred A. Knopf. $26.95.

The premise of this tiresome new novel by the critically acclaimed author Norman Rush sounds as if it had been lifted straight from “The Big Chill”: a group of now middle-aged college friends reunite to commemorate the death of one of their own. The result not only lacks that movie’s humor and groovy soundtrack but is also an eye-rollingly awful read.

The novel’s preening, self-absorbed characters natter on endlessly about themselves in exchanges that sound more like outtakes from a dolorous group therapy session than like real conversations among longtime friends. Its title, “Subtle Bodies” – which refers to people’s “true interior selves,” whatever that means – is a perfect predictor of the novel’s solipsistic tone. Readers given to writing comments in their books are likely to find themselves repeatedly scrawling words like “narcissistic,” “ridiculous,” “irritating” and “pretentious” in the margins.

There has always been a strain of self-consciousness in Mr. Rush’s writing, but in his earlier books, set in Botswana, where Mr. Rush once worked in the Peace Corps, the African setting provided him with an opportunity – brilliantly seized in his debut collection of stories, “Whites” – to exercise his reportorial eye and to place his characters’ personal dilemmas within the larger context of Westerners’ trying to come to terms with Africa and its colonial past. With each book since “Whites” (that is, the National Book Award-winning “Mating,” from 1991, and “Mortals,” 2003) his narratives and characters have grown more inner-directed: a process that has reached its cloying culmination in “Subtle Bodies.”

Although most of this novel is set on an estate in the Catskills shortly before the 2003 invasion of Iraq, it actually takes place largely inside the heads of a political activist named Ned and his possessive wife, Nina – who both, it quickly becomes apparent, live within the Mylar bubble of their marriage, obsessively dissecting each other’s emotions and moods. Ned thinks of Nina as “his honey monkey.” Nina thinks of Ned as “a sort of Jesus, a secular Jesus.” When Ned and Nina both wear jeans, she thinks of them as “a symphony in denim.”

Ned has rushed from California to the Catskills, where his friend Douglas has just died, and Nina has followed in hot pursuit because she’s ovulating now and wants to have a child; she’s furious that he’s picked this moment to get on an airplane without her.

Back in the 1970s, we learn, Ned was part of a clique at New York University, a band of students, who, as Nina understands it, thought of themselves as “a group of wits,” “superior sensibilities of some kind.” They were the sort of folks who referred to themselves as “cineastes” because they went to movies at the Thalia. They liked to use words like “outré,” referred to graffiti artists as “ulterior decorators” and said that “Pinot Noir meant don’t urinate at night.” When they listened to records, no one was allowed to speak.

Douglas (who seems to have driven a lawn mower too close to the edge of a ravine) was the leader of the pack. Reminiscent of the charismatic genius figures in Iris Murdoch novels, he was an intellectual guru for the others, though it’s baffling why anyone would look up to such a pompous jerk.

Douglas picked up his college girlfriend Claire with the line “I stand here lonely as a turnstile,” and found it amusing to insert the word “egad” into every answer he gave in a class. One of the group remembers that Douglas “wished if we all outlived him, we would go to some park and hide in the trees, and when somebody came by, we would shout, ‘Great Pan is dead.’ ”

This jokester attitude infected Douglas’s child rearing as well: he named his son Hume, after the philosopher David Hume, and encouraged him to be as outrageous as possible. Hume has grown up to be a feral teenager with a double Mohawk haircut; he often lives off by himself in the woods in a cabin or a yurt.

The media are arriving to cover the memorial service for Douglas because he was “half-famous in the world” for debunking forgeries: “He’d proved that some sensational papers revealing that Alfred Dreyfus was in fact guilty of espionage were right-wing forgeries” and had shot down forgeries of “Milan Kundera’s so-called ‘Love Diaries.’ ”

There’s a lot of mumbo-jumbo about Douglas’s philosophy – it’s said that he was “proposing various universal solutions to the problem of the persistence of evil in the world, in human relations” – and more portentous gibberish about his current mysterious work: Nina says she’s learned that “he took something called special commissions. Which means that he did work for the German Bundes-something and for the Israelis.”

The other members of this novel’s cast are either as insufferable as Douglas or as flimsy as paper-doll mannequins. There’s Elliot, an officious stockbroker who made riskier and riskier bets in the market and seems to have lost a lot of his friends’ money. There’s Gruen, a chubby fellow who owns an agency that makes public service announcements for TV and who used to serve as “everybody’s confessor.” And there’s Joris, who goes to prostitutes for sex because he regards himself as a “married-woman fetishist” who would ruin any marriage he undertook the same way he ruined his first one; he rarely sees his two sons from that union, and says that “maritime law was a perfect field for him because absolute cynicism was the best Weltanschauung to have if you were in it, because the field was strewn with pirates and crooks.”

Perhaps Mr. Rush means all this to read as black comedy, but it’s not remotely funny or compelling. In fact, it’s impossible to work up any interest in hearing what these absurdly self-important and poorly drawn characters might have to say as they drone on about themselves, with some random asides about Islam, Dadaism, anti-Semitism and abstract matters like “the sublime of deeply comprehending the world.”

At one point, Ned says to Nina, “Why are we even talking about this?” It’s a question the reader might well ask about this claustrophobic and totally annoying novel.

No comments yet.

Add your comment