5 Brilliant Short Peace Corps Writers Stories (Eastern Caribbean, Mali, Zaire,Tonga, Mongolia)

The Mending Fields

By Bob Shacochis (Eastern Caribbean 1975–76)

I WAS ASSIGNED to the Island of Saint Kitts in the West Indies. Once on an inter-island plane, I sat across the aisle

from one of my new colleagues, an unfriendly, overserious young woman. She was twenty-four, twenty-five . . . we were all twenty-four, twenty five. I didn’t know her much or like her. As the plane banked over the island, she pressed against the window, staring down at the landscape. I couldn’t see much of her face, just enough really to recognize an expression of pain. Below us spread an endless manicured lawn, bright green and lush of sugarcane, the island’s main source of income. Each field planted carefully to control erosion. Until that year, Saint Kitts’ precious volcanic soil had been bleeding into the sea; somehow they had resolved the problem. The crop was now being tilled in harmony with the roll and tuck of the land and the island had taken a step to reclaiming its future. The woman peered out her window until the island was lost on the blue horizon. And then she turned forward in her seat and wept until she had soaked the front of her blouse. “Good Lord,” I thought, “what’s with her?” I found out later from another Volunteer: Two years ago, having just arrived on the island, she had been assaulted as she walked to her home. Not content to rape her, a pair of men had beaten her so severely she was sent back to the States to be hospitalized. Recovering, she had made the choice to return. She believed she could be of use on Saint Kitts so she went back to coordinate the team responsible for improving the way sugarcane was cultivated. The day I flew with her was the first time she had taken a look at her handiwork from the illuminating vantage of the air. The cane fields were beautiful, perfect: they were a triumph, they were courage, and they were love. Bob Shacochis (Eastern Caribbean 1975–76)

Water

Rachel Schneller (Mali 1996–98)

When a woman carries water on her head, you see her neck bend outward behind her like a crossbow. Ten liters of water weighs twenty-two pounds, a fifth of a woman’s body weight, and I’ve seen women carry at least twenty liters in aluminum pots large enough to hold a television set.

To get the water from the cement floor surrounding the outdoor hand pump to the top of your head, you need help from the other women. You and another woman grab the pot’s edges and lift it straight up between you. When you get it to the head height, you duck underneath the pot and place it on the wad of rolled-up cloth you always wear there when fetching water. This is the cushion between your skull and the metal pot full of water. Then your friend lets go. You spend a few seconds finding your balance. Then with one hand steadying the load, turn around and start your way home. It might be a twenty-minute walk through mud huts and donkey manure. All of this is done without words.

It is an action repeated so many times during the day that even though I have never carried water on my head, I know exactly how it is done.

Do not worry that no one will be at the pump to help you. The pump is the only source of clean drinking water for the village of three thousand people. Your family, your husband and children rely on the water on your head; maybe ten people will drink the water you carry. Pump water, everyone knows, is clean.

Drinking well water will make you sick. Every month, people here die from diarrhea and dehydration. The pump is also where you hear gossip from the women who live on the other side of the village. Your trip to the pump may be your only excuse for going outside of your family’s Muslim home alone.

When a woman finds her balance under forty pounds of water, I see her eyes roll to the corners in concentration. Her head makes the small movements of the hands of someone driving a car: constant correction. The biggest challenge is to turn all the way around from the pump to go home again. It is a small portion of the ocean, and it swirls and lurches on her head with long movements.

It looks painful and complicated and horrible for the posture and unhealthy for the vertebrae, but I wish I could do it. I have lived in this West African village for two years, but cannot even balance something solid, like a mango, on my head, let alone a pot filled with liquid. When I lug my ten liter plastic jug of water to my house by hand, it is only a hundred meters, but the container is heavy and unwieldy. Changing the jug from one hand to the other helps, but it is a change necessary every twenty meters. Handles do not balance. On your head, the water is symmetrical like the star on top of a Christmas tree. Because my life has never depended on it, I have never learned to balance.

It looks painful and complicated and horrible for the posture and unhealthy for the vertebrae, but I wish I could do it. I have lived in this West African village for two years, but cannot even balance something solid, like a mango, on my head, let alone a pot filled with liquid. When I lug my ten liter plastic jug of water to my house by hand, it is only a hundred meters, but the container is heavy and unwieldy. Changing the jug from one hand to the other helps, but it is a change necessary every twenty meters. Handles do not balance. On your head, the water is symmetrical like the star on top of a Christmas tree. Because my life has never depended on it, I have never learned to balance.

This essay “Water” won the RPCV Writers & Readers Peace Corps Experience Award in 1998.

I Had A Hero

Mike Tidwell (Zaire 1985–87)

IN ONE HAND HE CARRIED a spear, in the other a crude machete. On his head was a kind of coonskin cap with a bushy tail hanging down in back. Around his neck was a string supporting a leather charm to ward off bad bush spirits. Two underfed mongrel dogs circled his bare feet, panting.

“My name is Ilunga,” he said, extending his hand.

“My name is Michael,” I said, shaking it.

We smiled at each other another moment before Ilunga got around to telling me he had heard my job was to teach people how to raise fish. It sounded like something worth trying, he said, and he wondered if I would come by his village to help him look for a pond site. I said I would and took down directions to his house.

The next day the two of us set off into the bush, hunting for a place to raise fish.

Machetes in hand, we stomped and stumbled and hacked our way through the savanna grass for two hours before finding an acceptable site along a stream about a twenty-minute walk from Ilunga’s village. Together, we paced off a pond and staked a water canal running between it and a point farther up the stream. Then, with a shovel I sold him on credit against his next corn harvest, Ilunga began a two-month journey through dark caverns of physical pain and overexertion. He began digging.

There is no easy way to dig a fish pond with a shovel. You just have to do it. You have to place the tip to the ground, push the shovel in with your foot, pull up a load of dirt, and then throw the load twenty or thirty feet to the pond’s edge. Then you have to do it again — tip to the ground, push it in, pull it up, throw the dirt. After you do this about 50,000 times, you have an average-sized, ten-by-fifteen-meter pond.

But Ilunga, being a chief and all, wasn’t content with an average-sized pond. He wanted one almost twice that size. He wanted a pond fifteen by twenty meters. I told him he was crazy, as we measured it out. I repeated the point with added conviction after watching him use his bare foot to drive the thin shovel blade into the ground.

For me, it was painful visiting Ilunga each week. I’d come to check on the pond’s progress and find Ilunga grunting and shoveling and pitching dirt the same way I had left him the week before. I winced each time his foot pushed the shovel into the ground. I calculated that to finish the pond he would have to move a total of 4,000 cubic feet of dirt. Guilt gnawed at me. This was no joke. He really was going to kill himself.

One week I couldn’t stand it any longer.

“Give me the shovel,” I told him.

“Oh no, Michael,” he said. “This work is too much for you.”

“Give it to me,” I repeated, a bit indignantly. “Take a rest.”

He shrugged and handed me the shovel. I began digging. Okay, I thought, tip to the ground, push it in, pull it up, throw the dirt. I did it again. It wasn’t nearly as hard as I had thought. Stroke after stroke, I kept going. About twenty minutes later, though, it got hot. I paused to take off my shirt. Ilunga, thinking I was quitting, jumped up and reached for the shovel.

“No, no,” I said. “I’m still digging. Sit down.”

He shrugged again and said that since I was apparently serious about digging, he was going to go check on one of his fields.

Shirtless, alone, I carried on. Tip to the ground, push it in, pull it up, throw the dirt. An hour passed. Tip to the ground, push it in, pull it up . . . throw . . . throw the . . . dammit, throw the dirt. My arms were signaling that they didn’t like tossing dirt over such a great distance. It hurts, they said. Stop making us do it. But I couldn’t stop. I had been digging a paltry hour and a half. I was determined to go on, to help Ilunga. How could I expect villagers to do work I was incapable of doing myself?

Sweat gathered on my forehead and streamed down my face as I continued, shoveling and shoveling. About thirty minutes passed and things started to get really ugly. My body buckled with fatigue. My back and shoulders joined my arms in screaming for an end to hostilities. I was no longer able to throw the dirt. Instead, I carried each load twenty feet and ignobly spooned it onto the dike. I was glad Ilunga wasn’t around to see this. It was embarrassing. And then I looked at my hands. Both palms had become blistered. One was bleeding.

Fifteen minutes later, my hands finally refused to grip the shovel. It fell to the ground. My back then refused to bend down to allow my arms the chance to refuse to pick it up. After just two hours of digging, I was incapable of doing any more. With a stiff, unnatural walk, I went over to the dike. Ilunga had just returned, and I collapsed next to him.

“I think I’ll stop now,” I managed, unable to hide my piteous state. “Take over if you want.”

He did. He stood up, grabbed the shovel and began working — smoothly, confidently, a man inured to hard work. Tip to the ground, push it in, pull it up, throw the dirt. Lying on my side, exhausted, I watched Ilunga. Then I looked hard at the spot where I had been digging. I had done nothing. The pond was essentially unchanged. I had moved perhaps thirty cubic feet of dirt. That meant 3,970 cubic feet for Ilunga.

Day after day, four or five hours each day, he kept going. He worked like a bull and never complained. Not once. Not when he hit a patch of gravel-size rocks that required a pickaxe and extra sweat. Not when, at the enormous pond’s center, he had to throw each shovel-load twice to reach the dikes. And not when he became ill.

Several weeks later, Ilunga drove his shovel into the earth and threw its load one last time. I never thought it would happen, but there it was: Ilunga’s pond, huge, fifteen by twenty meters, and completely finished. Using my motorcycle and two ten-liter carrying bidons, I transported stocking fish from another project post twenty miles to the south. When the last of the 300 tilapia fingerlings had entered the new pond, I turned to Ilunga and shook his hand over and over again.

Ilunga had done it. He had taken my advice and accomplished a considerable thing. And on that day when we finally stocked the pond, I knew that no man would ever command more respect from me than one who, to better feed his children, moves 4,000 cubic feet of dirt with a shovel.

I had a hero.

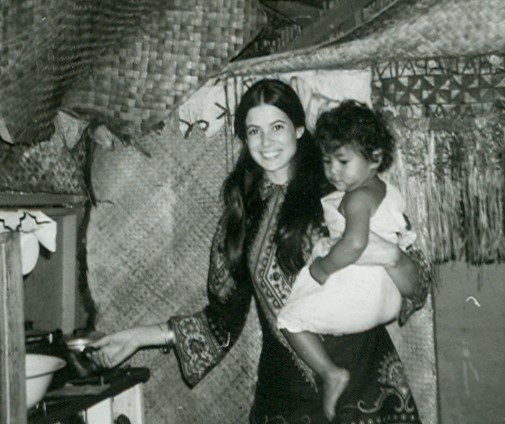

Under the Tongan Sun

Tina Martin (Tonga 1969–71)

I LIVED IN A TINY HUT made of bamboo and coconut leaves and lined with dozens of mats, pieces of tapa cloth,  and wall-to-wall children. When I sat on the floor with my back against the back door, my feet almost touched the front door. There was no electricity or running water, so I used a kerosene lamp and drew water from the well. There were breadfruit trees and avocado trees around my hut, and if I wanted a coconut, the children climbed a tree for me.

and wall-to-wall children. When I sat on the floor with my back against the back door, my feet almost touched the front door. There was no electricity or running water, so I used a kerosene lamp and drew water from the well. There were breadfruit trees and avocado trees around my hut, and if I wanted a coconut, the children climbed a tree for me.

The kids I taught were always with me, and I loved them even more than I once loved my privacy. I always wanted to have children, but I never thought I’d have so many and so soon. These were the children I would like to see back home — children who had never even seen a television set and didn’t depend upon “things” for their entertainment because they didn’t have any things. For fun, they taught each other dances and songs, and they juggled oranges.

They woke me up in the morning, calling through my bamboo poles. They took my five sentini and got me freshly baked bread from the shop across the lawn, and they helped me eat it. Some of them watched the ritual of my morning bath-water drawn from the well and heated on my kerosene stove and poured into a tin, then over a pre-soaped me. They sometimes braided my hair and helped me get dressed for school. Then they walked me there, where I used the oral English method we learned in training — acting out the language so there’s no need for translation.

“I’m running! I’m running!” I said as I ran in front of the class. “I’m running. I’m running!” I took a child by the hand.

“Run!” I said, and eventually he did. The goal was to have a running paradigm, which usually ended. “I running, you running, he/she/it running.” We did this for all verbs.

English was the link between Tonga and other land masses. And English was the exercise that kept me scrawny, the worst physical defect a body could have in the Tongan culture, where fat was beautiful. I tried to compensate for my lack of bulk by being very anga lelei (good-natured), which was their most cherished personality trait.

After school the children would come home with me and stay, singing Tongan songs and the ones I’d taught them.

Then I tried to help them prepare for the sixth grade exam that would determine their scholastic future. And they helped me prepare whichever vegetable was to be my dinner.

The children never left until I was safely tucked into bed under my canopy of mosquito net on top of tapa cloth. Then I blew out my lamp, laid down, and listened to songs from a kava ceremony nearby. Sometimes there was light from what a Tongan teacher told me was now the “American moon,” since we had put a man there. On moonless nights, I fell asleep in complete darkness. But I fell asleep knowing that I would always wake up under the Tongan sun. Tina Martin (Tonga 1969–71)

Cold Mornings

Matt Heller (Mongolia 1995–97)

OUR FAMILY ALWAYS LIVED where we needed a snow shovel. I remember one snowstorm in particular when I was nine. My best friend, Bobby Frost, and I shoveled our entire driveway ourselves, which is no small feat for nine year-olds.

When we were done, my father was waiting in the kitchen to reward us with grilled cheese sandwiches, tomato soup, and a silver dollar for the work we had done. Dipping my grilled cheese into the steaming tomato soup (in my opinion, truly the best way to eat the two together), I am sure I was oblivious to how lucky I was; how Norman Rockwell-beautiful shoveling a driveway can be.

Because I grew up in New England, winter was always my favorite season. It meant ice hockey, snow days off from school, and sledding until dinner was ready. Winter meant scratchy wool hats, scarves that always choked me, jackets that made me look like a mini-sumo wrestler, snow pants that made peeing an ordeal, and moon boots. My moon boots were my favorite. I may even have worn them to bed a few times, afraid someone would take them from me while I slept. I loved winter as much as I loved those moon boots.

I still love winter, but to say I enjoy it as I did when I was nine years old would be a lie. I’ve been a Peace Corps Volunteer in Mongolia for eighteen months now and I live in a ger, a tent with a small wood stove in the center. It is strong and practical, the perfect domicile for a nomadic herder living on the Asian steppe. It packs up in about half an hour. I, however, am not a herder, but an English teacher in a small secondary school in rural Mongolia. Ger life is not easy. It makes twenty year-olds look thirty-five. It makes your soul hard.

Mongolians are very proud of their history and traditions. Once, while sitting on the train going from Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, to my own town, Bor-Undur, a Mongolian pointed to his arm and said, “In here is the blood of Genghis Khan. Beware.” Really, there is no argument to that statement. I responded, “Yes, older brother (a respectful title addressed to elders), your country is beautiful. Mongolians are lucky people.”

Unfortunately, many Mongolians are big vodka drinkers, and this very drunk herder was on his way home from selling cashmere wool and meat in the city. He had been successful in his business, and celebrating now he wanted to teach me the custom of taking the traditional three shots of vodka that new acquaintances must drink. His shots were too big for me, and I only wanted to taste the vodka, not help him finish the bottle. That’s when Genghis’ blood came into the conversation. I drank the three shots. Herders are tough people. They don’t wear moon boots.

Maybe if I had been born here and lived in a ger all my life I would be tough too. But I wasn’t, and I’m not. I can trace no lineage to the man who was once the world’s most powerful ruler, but I am blessed. I am blessed with the gift of a Peace Corps/Mongolia standard issue sleeping bag rated to -30 degrees. When combined with another sleeping bag of my own and some wool blankets, I am completely protected from the cold that invades my ger every night when the fire goes out.

When it’s time to wake up and start my day, the first thing I do is build a fire. In the quiet darkness of morning,  huddling next to my stove and sipping hot coffee, I listen to the Voice of America on my shortwave radio and remind myself who I am, where I’m from, and what I’m doing. I’m a young Volunteer spending eight hours a day with Mongolians, building a greenhouse with the other teachers in my school so there will be more vegetables in our town. Along with many other things, I’m learning how they live. In the steppe there is very little snow, only biting wind and dust. It gets as cold as -50 degrees, not counting the wind chill factor. If I leave leftover tea in a mug, it will freeze solid by morning. I’ve broken three mugs that way. When it is this cold I sometimes ask myself, “How valuable is the contribution I’m making? And is it really worth being this cold?”

huddling next to my stove and sipping hot coffee, I listen to the Voice of America on my shortwave radio and remind myself who I am, where I’m from, and what I’m doing. I’m a young Volunteer spending eight hours a day with Mongolians, building a greenhouse with the other teachers in my school so there will be more vegetables in our town. Along with many other things, I’m learning how they live. In the steppe there is very little snow, only biting wind and dust. It gets as cold as -50 degrees, not counting the wind chill factor. If I leave leftover tea in a mug, it will freeze solid by morning. I’ve broken three mugs that way. When it is this cold I sometimes ask myself, “How valuable is the contribution I’m making? And is it really worth being this cold?”

For eighteen months now I’ve been waking up and thinking, yes, it is. I love working with Mongolians, but the time of day I look forward to most is building my morning fire. It is my time of epiphany. As I feel the warmth that my own hands created, a fire that pushes back the cold and the dark, replacing them with warmth and light, I know I will live another day. Such an experience defines what it means to be a Peace Corps Volunteer.

We all build fires in one way or another, and the warmth we create is as good as eating grilled cheese sandwiches and tomato soup on a winter day when you’re only nine years old. Being a Volunteer in Mongolia and having the opportunity to live in a ger may mean enduring very cold mornings, but it’s worth more than all the silver dollars in the world. Matt Heller (Mongolia 1995–97)

Indeed; these ARE brilliant! Thanks for posting them up and making my day! djn

Excellent stories, well told! Capture the PCV experience and the value of the PCV to the HCN’s and vice versa!! Bravo!

You are getting me excited about writing

These personal essays are certainly “brilliant,” well edited with all the fat neatly trimmed off. I read in some medical journal that fat can cause cancer!