Review: MEETING THE MANTIS by John Ashford (Botswana)

Meeting the Mantis: Searching for a Man in the Desert

Meeting the Mantis: Searching for a Man in the Desert

and Finding the Kalahari Bushmen

by John Ashford (Botswana 1990–92)

Peace Corps Writers

August 2015

216 pages

$13.00 (paperback), $4.00 (Kindle)

Reviewed by Julie R. Dargis (Morocco 1984-87)

•

“Follow the lightening,” the first people of the Kalahari said. At the end of the proverbial rainbow in Western culture, lies water, herds of wild animals, and life in the desert.

For years, John Ashford fantasized about what it would be like to live the life of a Bushman. After years of contemplation, the photograph of Freddy Morris that John Ashford had once glimpsed in his hometown library, came to life.

By the time the author met him, Freddy Morris had clocked nearly 90 years straddling two cultures. Before he set out on his journey, Ashford could lay claim to a half-life of Freddy’s experiences, the most relevant months boiled down to a two-year stint in Peace Corps as a teacher in Botswana during the middle part of his life.

Although Ashford was on the road for weeks, the lessons unfurled within days. A hundred pages into Meeting the Mantis, Ashford proclaims that he is in search of truth and desires to let go any romantic notions. Gazing upon the thirty-year-old photo of Freddy and his family, Ashford ponders all that was in his mind, expecting something unreal. But he soon finds that in the desert all roads lead to reality.

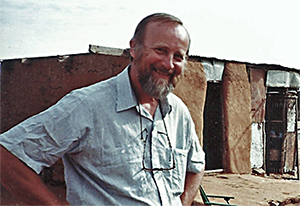

John during his visit with Freddy Morris

The school bells ring as Ashford kicks back on his metal chair. His direct questions to Freddy Morris had gone immediately unanswered. A throng of children return to the dusty compound to partake in their morning tea, and Ashford watches as each cup is filled with scalded goat’s milk and topped with sugar. After Freddy empties his own cup, he raises his hands to count his wives and children, but there are not enough fingers on either. The language between the two men, though English, initially escapes communication. “My daughter and my second wife, they be going,” Freddy says. Within moments, however, Freddy’s words are understood as bad luck to one is interpreted as life torn away to another. As Freddy Morris continues to pull at the roots of his family tree, Ashford chisels the notches.

In his telling, I had counted four wives and many offspring. But for Freddy the story of wives and children was not about ages or numbers at all. It was a personal drama of loyalty, infidelity, and loss. The answer had more to do with his heart than a number.

Ashford’s totem was also a shaman. But when he was no longer able to heal himself, Freddy Morris had stepped down from the helm of the monthly shamanic healing dances, which had zapped so much of the juice out of him over the years. His knowledge of traditional medicine had been kinder, however, and he still graciously doled out plant and mineral remedies to the villagers who came by each day.

Yet the remedy that Ashford was offered was neither herbal nor mineral. Instead, Ashford was infused with a diet of synchronicity. Out in the veld, he and his wife met and talked with the local artists whose work they had admired in an exhibit in Gaborone’s modern museum. They met John Hardbattle, an infamous hard-nosed advocate of the San. Ashford visited a settlement with an international aid worker from Denmark, a connection that Hardbattle had brokered.

“Please, I must ask you,” the aid worker cooed. “If you ever talk to someone in a government office or write about this, don’t put my name in the same sentence with John’s.” Ashford agreed. But this was in the early ’90s. Within a round of leap years, his work with the San would be cut short, and John Hardbattle would be gone — struck down with an aggressive case of lymphoma at age 51.

Back at the hostel, Ashford speaks with his wife about all he is learning. As his wife draws an analogy to Ashford’s relationship with his deceased father, a singular quest is transformed into a pathway to healing. “Parallel journeys,” she says. “You travel across the desert. You piece together fragments of an old man’s story,” his wife gently chides him. “Then, whose story is it?”

But what started with the San, ends with the San. And reality once again trumps romantic notions. Ashford is surprised at the abrupt goodbye that he shares with Freddy Morris after a short walk through the village. Ashford quickly understands as he turns back to look at Freddy who is hastily relieving himself by the side of the road. After the dust has settled, Ashford continues to share his story. Through his words, the plight of the San is resurrected.

•

Reviewer Julie R. Dargis is a poet, a writer, and an intuitive. She is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Integral Health at the California Institute for Human Science in Encinitas, California.

To purchase the books mentioned here from Amazon.com, click on the book cover, the bold book title, or the publishing format you would like, and Peace Corps Worldwide — an Amazon Associate — will receive a small remittance that will help support the site and the annual Peace Corps Writers awards.

•

Read more about Meeting the Mantis

Ashford’s book gets beyond the “numbers” to the underlying factors which cause people to do what they do in different cultural settings. Can’t wait to read it. Julie’s review brings these nuances out very eloquently–you’d think she was a poet.