The Peace Corps in Washington–The Early ’60s

There are unfortunately few books about the early days of the agency, how it was formed and who was involved in those weeks at the Mayflower Hotel and in the original Peace Corps Office, the Maiatico Building, located at the edge of Lafayette Park and within sight of the White House.

Who were the people who built the agency? Harris Wofford’s book, Of Kennedys & Kings Making Sense of the Sixties (1980) devotes a chapter to the Peace Corps. The Bold Experience: JFK’s Peace Corps by Gerard T. Rice (1985) tells of the political maneuvering to create the agency, as does to a certain degree, All You Need Is Love: The Peace Corps and the Spirit of the 1960s by Elizabeth Cobbs Hoffman (1998).

However, Come As You Are: The Peace Corps Story by Coates Redmon (1986) a press writer at the Peace Corps in its first days, gives the background of many early employes—who they were and how they why they wanted to work for the Peace Corps.

So, in an attempt to “put down on paper” (or at least on the Web) the names and stories of the people who created the agency, I am going to draw on a few sources, and the recollections I have of those days, some old writings as well, and get down in one place what it was like in the early ’60s inside HQ. I invite everyone to add these stories (as comments) of the first years when the Peace Corps was located at 806 Connecticut Avenue.

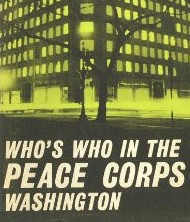

One source that I have is a small pamphlet entitled Who’s Who in the Peace Corps Washington, printed and published, not at government expense, in 1963. It gives short bios of many of the key people who came to Washington in 1961.

The Staff

The first Peace Corps Staff in Washington, D.C., came from every background, from all economic levels and from every part of the country. They were skiers, mountain climbers, big-game hunters, prizefighters, football players, polo players and enough Ph.D’s. (30) to staff a liberal arts college.

They also included 18 attorneys, of whom only four continued to work strictly as attorneys in the General Counsel’s office and the rest (including Sargent Shriver) applied their lawyer’s training to other jobs in the agency.

The first Peace Corps Staff was composed of people who showed all the individual differences seen in the first Volunteers selected to service.

Figures from WW II indicated that 30 persons were required to support every soldier in the front lines. In peacetime, in the early 60s, the ratio changed from one person in Washington to every four Volunteers overseas.

The Peace Corps in the early days was organized with the goal of ten Volunteers on the job for very administrative or clerical person in support, and that meant everyone—clerks, typists and overseas administrators included.

Shriver knew that such a ratio was only possible because of the high quality of the Volunteers overseas and because their support people in Washington worked as hard as the Volunteers did around the world.

Next, I’ll write about what Shriver had to say about the first Staff working days, nights and weekends in the Maiatico Building.

Note: The photo above is from the front pages of the Washington Post showing the Maiatico Building ablaze with lights. It showed that the Peace Corps Staff was working far into the night. They were the only federal employees so engaged.

What about Stanley Meisler’s “When the World Calls” – great history of the Peace Corps and its people.

Roy Hoopes did a couple of books about the PC when little was really known.

Good point, Liz. Stan, who was a friend of mine, came to work early in ’64. At the moment, I am focused on 1961,’62, and ’63.

John,

Will you be writing about 1964? To me, that is absolutely the most significant year because of all the changes and what they implied. Kennedy was gone, Shriver was working only part time, Moyers was gone to the White House, and Charlie Peters’ evaluation unit was just beginning to bring back information from the field. I was in -country just three and half weeks before the assassination. I don’t know what Peace Corps was like before then.

The photo shown above is the cover I made for Who’s Who in the PC. We didn’t know what to show, but this idea worked. There weren’t many, if any, photographs from the field that would have worked. I’m glad it was understood by John Coyne as it showed we worked “far into the night”, but to be honest that really wasn’t the intention. It was just a snap that showed where we all were. Designer Paul Reed, a brilliant fine artist who put his career on hold to be the art director, added the tone. We didn’t have the money for a full color magazine. I believe I did every picture save one in that piece. We were proud of it.

PS The great James Thompson Walls, “Jim”– did the interviews and the writing.

In the Evaluation Division, if you tried to sneak out before six p.m., Charlie Peters would yell sarcastically, “Department of Agriculture!” That division, by the way, was up and running and sending back useful reports by late 1961.

Dick,

Thanks for the update. Were you in Peace Corps Washington in 1964? Any insight would really be appreciated. I focus on that year for two reasons. One is personal. It was my first full year as Volunteer in Colombia and I don’t know how much of what we experienced was a reflection of what was happening stateside. More importantly, I see Peace Corps, as an unique organization, extremenly vulnerable during times of transition. I see the transition from Kennedy to Johnson as one of those times. Certainly, the most famous was from Johnson to Nixon. I also think that we are in a very vulnerable time right now for the organization. The more we know about transitions, I think the better we can support Peace Corps.