“Loose Ends” by Bob Criso (Nigeria/Somalia)

Loose Ends

by Bob Criso (Nigeria 1966-67, Somalia 1967-68)

•

SUSAN STEEN AND PAUL BAUMER met on a beach in Bali. She was traveling with her friend Janice, taking a lot of pictures with her fancy camera. He was on his way home after two years with the Peace Corps in Africa. They have sex in the moonlight. It was 1970.

“What was it like?” Susan asks, sitting up on the blanket and lighting a cigarette.

Paul tells her about his early Peace Corps success. He and his friend Jeff “worked their asses off” and got all the latrines built for their project in only six months, thanks to a lot of help from the locals. He became fluent in Nglele. When the locals didn’t use the latrines, he learned that they use feces as fertilizer and didn’t want to waste it in the latrines. All along, the locals had assumed that Paul and Jeff were there as some kind of punishment and would leave once the latrines were finished. When they didn’t leave, they thought they were societal outcasts and distanced themselves from them. Paul and Jeff then thought about setting up a health program. They consulted with a doctor and used their own money to order a list of medications. When the medications were never delivered, they went to meet with the Minister of Health, the man who had requested Peace Corps volunteers in the first place. He was a friendly fellow, British-educated with leather bound copies of Dickens and Thackeray in his office. He said he admired their efforts, but he couldn’t do anything because of orders from higher-ups. Paul and Jeff knew he was lying. Then the Minister asked them if they would be willing to feed and house the people whose lives they saved with the medications for the next ten or twenty years or until they died. Paul and Jeff found hookers, spent a week fucking their brains out, then got stoned and started counting the days until they went home.

“I spent two years going through a lot of very weird stuff,” Paul tells Susan, “but when I try to talk about it, it’s just a story. Just some stuff that happened and now it’s over. It doesn’t mean anything anymore.”

Any of it sound familiar? All of the above is from the first act of Michael Weller’s play “Loose Ends” which opened in New York in 1979. I reviewed it recently when it was revived in an off-Broadway production. The author uses the Peace Corps as a metaphor for youthful romantic notions that go awry, things that initially seem promising then get crushed when faced with harsh realities. He’s examining the idealism of the sixties and views it through the lens of Paul and Susan’s relationship. It’s a coming-of-age play about innocence, idealism, starry-eyed ideas, disappointment, disillusionment and maturity. How does a young and callow altruist like Paul deal with failure? How do you avoid becoming a pessimistic cynic after a major disappointment? What impact does that experience have on the rest of your life? How many Peace Corps Vvolunteers have felt under-prepared for an assignment, felt frustrated in dealing with an unfamiliar culture, had their well-intentioned efforts flattened by things beyond their control?

The play also chronicles the seventies, that in-between decade when the counter-culture hippies began to fade and the consumerist yuppies hadn’t arrived yet. It explores the issues of twenty-somethings, but maybe with particular relevance for anyone who has spent two years in a third world country. I’m twenty five, what do I do now? Should I go back to school? Where do I want to live? Do I want to be near my family? For many young men before the lottery, it was about dealing with the draft. Would I be willing to fight in Viet Nam? (“Moonchildren,” an earlier play by Mr. Weller, chronicles the free-love and protest era of the sixties by following a group of college students living together in an apartment. Weller’s plays are often part drama, part sociology class.)

I had my own bouts with frustration and disillusionment in the Peace Corps. In Somalia, my students knew little English and saw little purpose in education. They seemed resigned to living the lives their parents lived and wanted to just survive as best they could in a rough environment and one of the poorest countries in the world. It’s was as if hope and change were not in their vocabulary. I questioned why the Peace Corps was even there in the first place and wondered if we were being used as political pawns to counterbalance the much stronger Soviet and Chinese presence in the country at the time. My students in Nigeria, on the other hand, valued education highly and worked hard, hoping to get scholarships and study abroad like some of the school’s previous graduates. It all seemed so promising until the Biafran war came and the school was abruptly shut down and turned into army barracks. I learned later that a majority of those students lost their lives during the war. For many of them, their education represented the pooled efforts of a village to have one of it’s own succeed. We never talked about failure and disillusionment in training. Those attractive Peace Corps ads on television and in glossy magazines never hinted at that kind of ending.

No doubt many Peace Corps Volunteers did and continue to do some fine work, but I can remember plenty of stories about the frequent in-country disasters that turned well-intentioned Volunteers into frustrated pessimists. In Nigeria, dealing with a corrupt and inefficient government bureauocracy stifled a number of rural development programs. How many Peace Corps teachers found their principals impossible to deal with? When an agricultural program failed to materialize in Somalia, a small group of Volunteers started a band and went around the country playing gigs wherever they could. Pretty strange when most of the country was nomadic and had little familiarity with “House of the Rising Sun,” their signature song. Odder still was the blessing and the funding that the Peace Corps Director gave them, including a trip to Aden to buy instruments.

Prior to the Peace Corps my tentative plan was to study Chaucer in graduate school and then teach in college. The hard knocks that I took in Nigeria and Somalia changed my ivory-tower thinking. I returned to the states not knowing what I wanted to do, but definitely geared toward working with people — a consequence, at least partly, of the gratifying relationships I had with many Nigerians. I started with a teaching job in the New York City public schools and ended up, ironically, in an ivory-tower university, but with Counseling and Psychological Services, not the English Department.

Back to the play.

Susan stayed in Bali and wanted Paul to stay with her. “Stay here, it’s cheap,” she said trying to entice him, but Paul was restless and wanted to get on with his life. He had a teaching job at a private school waiting for him at home. He leaves, but they eventually hook up again in Boston. They move in together and pursue careers in photography and film editing. The playwright contrasts them with their seventies social circle. Susan’s sweet but somewhat ditzy friend, Janice, finds a guru-type boyfriend in Russell, but ends up marrying Phil, a reliable straight-shooter. Ben, Paul’s older brother, is a highly successful business type, a lifestyle Paul disparages. Paul’s friend Doug and his wife Maraya continue their hippie sixties ways, living close to the land as rural homesteaders and having babies.

Paul becomes a successful film editor, Susan a successful photographer. Their relationship goes through its ups and downs — they marry, she wants to move to New York, he doesn’t, he wants kids, she wants a career, she has a secret abortion, he finds out and they eventually split up. By 1979, the end of the decade and the end of the play, they meet again when Paul shows up at Susan’s cabin in New Hampshire. They have sex, but it’s clear their relationship isn’t going to work — more disappointment for Paul. He never told Susan he was coming and she has a previously planned date that night. It’s an awkward but poignant scene.

A car beeps outside. “Put some logs on the fire before you leave,” Susan says — she’s telling him she’ll be back later with her date. Paul pulls a curtain aside and watches as they drive off.

Self-discovery can be a rough road. Paul went from frustration in Africa to a hedonistic beach in Bali to some cold realities in the New Hampshire woods. He had his “loose ends” to tie up.

And so did we.

•

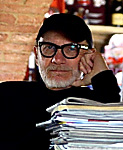

Bob Criso

Bob Criso had a half-time private psychotherapy practice in Princeton, NJ and a half-time position at Princeton University Counseling and Psychological Services. Now retired, he is a writer, theater critic, photographer and traveler. He recently returned from a trip to South Africa. (bobcriso@gmail.com)

I appreciated the reference to Michael Weller’s play, “Loose Ends.” When I first returned to the U.S. after my Peace Corps stint in Chad, I got involved in community theatre and was cast as “Russell”, the mystical guru type character in the play. It was a lot of fun, but the references in the play to some of the frustrations we dealt with in the Peace Corps rang true for me. Nonetheless, what I took away from Peace Corps was that sense that even when the obstacles seem overwhelming, we can thrive by channeling energies into more productive pursuits. We may come up against an impossible problem to solve but rather than letting that stymie us when various efforts don’t resolve it, we don’t have to remain stuck continuing to solve an intractable problem. Move on to something you can achieve that makes the lives of those around you better.

I think the trick is knowing when it is wise to persevere and when it is wise to cut your losses.

I was a Peace Corps volunteer in Nepal, with 38 other men, most of whom have spent their lives in service to others in one way or another. Failures of the type described in this article mostly derived from their initial inexperience of PC with situating volunteers in difficult situation. A modern volunteer will be well-trained in language and cross-culturally, and located with people and community who know what he is there for; not a suspect CIA agent. No single PC story (the lousy ones get most of the press) is illustrative of PC experience and impact. The author of this play comes across through his story as being shallow, self-pitying, and immature. Perhaps many were immature. I was fortunate to have been part of a group which, despite ilts collective inexperience, was for the most part able to function in a very unstructured and ambiguous situation; whose lives changed for the better as a result, and who have remained dedicated to the country and citizens who they served for the rest of their lives. Nick Ecker-Racz PC Nepal II (1963-65.

I distinctly remember a PC band that played at the British Club in Hargeisa and I wonder if it’s the band you mention. I was 9 years ols, the step son of Jack (John) MacDonald the US consul in Hargeisa. My mother was Mireya Zell, my name Robert Ransley.