How To Write Your Peace Corps Story

What is Creative Non Fiction?

&

Writing Your Peace Corps Story

by John Coyne (Ethiopia 1962-64)

Lee Gutkind who started the first Creative Nonfiction program at the University of Pittsburgh writes simply that “creative nonfiction are “true stories well told.”

In some ways, creative nonfiction is like jazz — it’s a rich mix of flavors, ideas, and techniques, some of which are newly invented and others as old as writing itself. Creative nonfiction can be an essay, a journal article, a research paper, a memoir, or a poem; it can be personal or not, or it can be all of these.

Creative nonfiction is also known as literary nonfiction or narrative nonfiction and is a genre of writing that uses literary styles and techniques to create factually accurate narratives. Creative nonfiction contrasts with other nonfiction, such as academic or technical writing or journalism, which is also rooted in accurate fact, but is not written to entertain based on writing style or florid prose.

The words “creative” and “nonfiction” describe the form. The word “creative” refers to the use of literary craft, the techniques fiction writers, playwrights, and poets employ to present nonfiction — factually accurate prose about real people and events — in a compelling, vivid, dramatic manner. The goal is to make nonfiction stories read like fiction so that your readers are as enthralled by fact as they are by fantasy.

The word “creative” has been criticized in this context because some people have maintained that being creative means that you pretend or exaggerate or make up facts and embellish details. This is completely incorrect. It is possible to be honest and straightforward and brilliant and creative at the same time.

“Creative” doesn’t mean inventing what didn’t happen, or reporting and describing what wasn’t there. It doesn’t mean that the writer has a license to lie. The cardinal rule is clear — and cannot be violated. This is the pledge the writer makes to the reader — the maxim we live by, the anchor of creative nonfiction: “You can’t make this stuff up!”

For one text to be considered creative nonfiction, it must be factually accurate, and written with attention to literary style and technique. Mr. Gutkin has said: “Ultimately, the primary goal of the creative nonfiction writer is to communicate information, just like a reporter, but to shape it in a way that reads like fiction.”

Literary critic Barbara Lounsberry — in her book The Art of Fact: Contemporary Artists of Nonfiction — suggests four constitutive characteristics of the genre.

- The first of which is “Documentable subject matter chosen from the real world as opposed to ‘invented’ from the writer’s mind.” By this, she means that the topics and events discussed in the text verifiably exist in the natural world.

- The second characteristic is “Exhaustive research,” which she claims allows writers “novel perspectives on their subjects” and “also permits them to establish the credibility of their narratives through verifiable references in their texts.”

- The third characteristic that Lounsberry claims is crucial in defining the genre is “The scene.” She stresses the importance of describing and revivifying the context of events in contrast to the typical journalistic style of objective reportage.

- The fourth and final feature she suggests is “Fine writing: a literary prose style.” Verifiable subject matter and exhaustive research guarantee the nonfiction side of literary nonfiction; the narrative form and structure disclose the writer’s artistry; and finally, its polished language reveals that the goal all along has been literature.

Before you put pen on paper, map out the journey you want to take in telling your story. What is–in your mind–the story you want to tell. Know your journey from the first page to the final chapter. You can do this by charting dates, events, months or seasons on a spread sheet or whiteboard.

Next, my suggestion to all writers–whether they are writing fiction or nonfiction– is that you capture the attention of your readers by writing a scene or a situation within the first paragraphs that will surprises, thrills, or amuse the reader. A scene that will grab the reader by the throat and keep her or him turning the page.

You do this, I suggest, by looking back over your two-year tour and recall the moment(s) when you realized your life had changed because you joined the Peace Corps. Begin there. Write that scene. Tell that story. Then continue your narrative. Fill your pages with whatever you remember or had already written down in your journal, diary, or letters home. Don’t worry about where it is going to be put in your book. Write it down! Once you start recalling your tour, you’ll remember more and more of it. I promise you that!

Then print out your pages (or put it on a file on your computer). Follow the ‘outline’ that you created, rewrite the book. Next, ask others to read your manuscript and give you their honest opinions. (Tell them not to be nice, or kind, but truthful.) Give it to RPCVs, as well as friends, and other writers. Join a Writing Group, if you can, and share with them your story. Your classmates will tell you their honest reactions, I promise you.

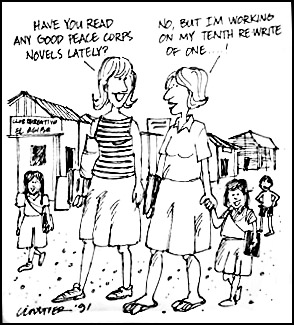

Then rewrite your story. Just remember one thing: all writing is rewriting. Keep rewriting and editing.

Here are a few suggestions about how to tell the story we all want to read!

- Pick a time and place where you will write everyday, or most days.

- Decide how many words you’ll write each day (Remember Hemingway was famous for writing 50 words a day. Then he’d go fishing.)

- Thing of one person to whom you are telling your story. Keep him or her in your mind as you write about the Peace Corps and your life.

- Begin each day by rereading and editing what you wrote the day before.

- Write scenes, situations, and stories of what happened to you as a PCV.

- Write about yourself, who you are, where you came from, and what you wanted out of the Peace Corps and out of your life.

- Describe your Peace Corps world and your Host Country Nationals (HCN).

- If you fall in love with the country, a HCN or another PCV, or what you did as a PCV, write about it.

- Tell us about your host family, village, and Peace Corps assignment. Don’t tell it all in one chapter, weave it into the narrative.

- As I said, create a story line. You were one person when you arrived overseas; you were someone else when you left for home after your Peace Corps service.

- Pick a title that says it all, but promises us more.

- Just remember one thing. Your life if important. What you write is important. We all want to read it, not just your mother and father.

What you have to realize is that your story is the Peace Corps story. Generations from now when historians ask, “what was the Peace Corps?” they will turn to what you wrote in your book. As a Peace Corps Volunteer you have a corner on American history. Tell your story so future generations will see how you as a PCV made a difference in the world.

Our whale attics are filled with the palest pieces of memory set into lost village anchorages. Some remain damaged communities where we’ve fled dissolving Into time atop some old pipelines and scarring hearts that we left behind. Strongest oaks long ago’ve fallen. Your odyssey is a far-off sea, now, & now your world’s personal history will remain an undiscovered world until you start to tell them and so of all the voyagers who’ve told theirs who then might you be then right now who sit wondering into the dawns coming.

Thank you for the good advice. I found that writing down my Peace Corps Odyssey brought back fond forgotten memories, good feelings and hurt feelings – mine and those I caused, minor unresolved issues and some large that I thought I left behind in Malaysia, and even repressed issues between my wife and myself.

It was the most emotionally difficult yet rewarding thing I’ve ever attempted but like a pebble in the heal of your shoe when you’re on a long hike and too tired to stop and take it out, it is such a relief and joy when you finally do. So sit down, or stand if you prefer, and write your Peace Corps Odyssey. The world will be the better for knowing what you’ve done, where you’ve been, what you’ve witnessed, who you’ve met and like and disliked, and who and how you’ve helped and offended them, and how you felt about it. One more thing, the people you’ve lived with, worked with, partied with, and mourned with deserve to have their story told through you.

Have you lost your journal or didn’t keep one? No problem. Start writing and you’ll be surprised at what you’ll remember and rediscover with the perspective and insight that only time can provide. Now stop reading and click on your desired writing app or grab some paper and a pencil and start writing your first 50 words.Your story will be the best ever told. There was never one like it before and there will never ever be another one like it again. Good writing, Jim Wolter, Malaya I, “61 – ’66