“East Meets West: An Account of a Trip to West Africa”

East Meets West

An Account of a Trip to West Africa – Summer, 1966

by Phillip LeBell (Ethiopia 1965-67)

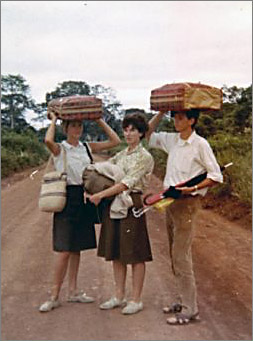

(l-r): Sudy Harris (1965-67 Kombolcha), Judy Hagens (1965-67 Kombolcha), and Phillip LeBel (1965-67) Emdeber. The photo was taken by Letitia (Tish) Coolidge (1965-67 Addis Ababa) at the border crossing from Dormaa Ahenkro, Ghana to the Ivory Coast frontier.

This is an account of a summer 1965 trip to West Africa of four Peace Corps Group IV volunteer teachers who flew from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, where we had begun our service tours in January of that year. We were: Sudy Harris and Judy Hagens (stationed in Kombolchia), Letitia (Tish) Coolidge (stationed in Addis Ababa), and me (stationed in Emdeber, Shoa province). We had known each other during our training at UCLA, California in the fall of 1964, but this was the first time we were reunited in this somewhat spontaneous adventure.

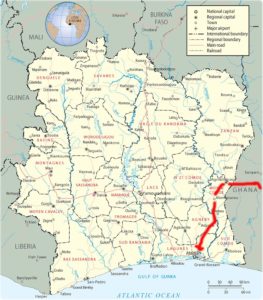

Attached is a general map of our West Africa trip, along with a map of the itinerary. Our first stop was in Khartoum, where we were well received by local residents who were both amused and surprised at our planned destinations in West Africa. Our next stop was in Njamena (Chad), where we found lodging at the Lycée Charles de Gaulle. Strolling through the dusty streets, we were able to negotiate with local Tuareg merchants in town, and then, to our surprise, found an air conditioned music store that was selling 33 vinyl classical music compositions. I don’t recall any African musical recordings being on sale, a configuration that today would most likely be just the opposite. Our next stop was in Kano, in northern Nigeria, where temperatures were a reminder of just how different the landscape was from the cooler highlands of Ethiopia from which we had come. Finally, our plane landed in Lagos, where we found lodging at a local rest house and from which we toured the city and planned our westward destinations: Dahomey (now Benin), Togo, Ghana, and finally, Côte d’Ivoire (marked as the Ivory Coast on English maps). We had obtained visas for each of these countries while still in Addis.

Without any clear plan, we contemplated either taking a boat from Lagos to Grand Bassam, Côte d’Ivoire, or take what was known then as a “bush taxi” (actually these were Peugeot 404 station wagons). We spoke with a captain in the Lagos harbor with the idea of maybe taking a boat trip all the way to Abidjan. When the captain saw me with three women, he asked if they were my wives, to which I promptly said “yes, of course”, with a barely contained howl of laughter). Well, we found the boat trip price a bit too much for our budget, and so we took the Peugeot bush taxi route.

We passed first through Cotonou, Dahomey (now Benin), then Lomé, Togo, then into Ghana. With time to swim at the beach in Lomé, Togo, we then crossed the border into Ghana. Our border customs officer greeted us with: “Welcome to Ghana, Star of Africa.” Excited to be that far on our route, we continued on to Accra, where we looked for a Peace Corps hostel at which to spend a few nights while exploring the city. We had Michelin maps, and a few travel tips, but nothing like a Lonely Planet guide, let alone mobile phones, Uber taxis, or a GPS.

At this time, Ghana was governed by Kwame Nkrumah, who since helping the then Gold Coast to achieve independence in 1957, was engaged in an effort to bring rapid industrialization somewhat on the lines of the Soviet industrialization program of the 1930’s. The idea was to bring self-sufficiency in industries that were traditionally import dependent. Nkrumah had become a leader of the Ghana CCP, or Convention People’s Party. Government revenues derived largely by a monopoly cocoa marketing board (cocoa was Ghana’s chief export revenue source), a policy recommendation of the now late Sir Arthur Lewis. Absent a revenue stream other than land taxes, the marketing board afforded an attractive means to fund government operations: government would guarantee a price floor on cocoa purchased from farmers which it would then sell at much higher prices in the largely London cocoa market. With this revenue stream, subsidies were granted to local firms to produce batteries, cement, and a number of other products in an effort to achieve economic self-sufficiency. Quality was poor, and consumer goods became scarce. I remember walking through a food supermarket in Accra and seeing largely empty shelves. But on the surface, things seemed to be moving with popular support as locals looked to ways to translate political independence into an economic counterpart.

After a visit in and around Accra, we took a bus up to Kumasi, a large town in the north where there was a Teacher’s College. Our plan was that, since there was no coastal route from the Ghanaian coast to neighboring Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), we would have to travel inland and then take a border crossing at a village known as Dormaa Ahenkro. From Kumasi, we took a bus to the village and looked to how we would then enter the Côte d’Ivoire. The problem is that Nkrumah’s leftward march estranged him from neighboring states, notably Côte d’Ivoire, then ruled by Félix Houphoüet Boigny. As a result, the borders were officially closed. Suspicion of travelers was on the rise. We were somewhat oblivious to as to how this might affect our trip, and so we were blithely determined to get to Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire’s capital on the coast.

While in Dormaa Ahenkro, I remember that we spent an evening at a local restaurant-hotel where we had some of the spicy hottest “chop” (meat cubes in a pepper sauce over a bed of rice) that I had ever tasted. There, locals told us that there were no vehicles that were making the border crossing due to the political tensions (neither had full diplomatic relations at the time). And so, we wound up walking several kilometers down a dirt road past first the Ghanaian border control past which we were simply walking through the tropical forest in Côte d’Ivoire where initially we saw virtually no one. That is the focus of the attached photo taken by Tish Coolidge.

Not so long after we crossed into Côte d’Ivoire, we were quickly surrounded by Ivoirian soldiers with machine guns demanding that we show our papers. We did so, and asked where we could catch a bus to Abidjan. They said they knew of none nearby, but if we could get to Agnibelokrou, we probably could find something there. With that reply, they let us continue walking to an as yet unknown destination where we were sure to find bus or taxi transport in the first town we would come across.

At about that time, we heard a motor grinding on in the distance. Even before we could see anything, we decided that if necessary, we would lie in the road to hitch a ride. It turns out that a group of Ghanaian instructors from the Kumasi Teachers College were taking a holiday trip to Freetown, Sierra Leone, and they were only slightly less apprehensive than we were with the uncertainties of border crossings. As they did not speak French, they agreed to take us on if I would serve as an interpreter, which I gladly offered to do. Motoring along, I remember at one point someone else asked the driver if we could stop for a bathroom visit. Seeing absolutely nothing but rain forest in sight, the driver slowed down and said “nice bush, lady”, meaning they would wait while some of us took our leave behind a bush. We did, and continued on our way.

Attached is a map of the Ivory Coast with an arrow indicating our crossing and road trip toward the capitol. Our first urban encounter of a town was at Agnibeloukrou. There we found a bus stop at the local Comissariat de Police, where our Kumasi Teachers College Chief of Party placed a call to the Ghanaian embassy in Abidjan to announce our impending arrival later in the evening. While waiting for permission to resume our trip, we heard desperate pleas from a mix of Ivoirians and Ghanaians who were begging to be released from nearby detention cells. That was not a good sign. Neither was the fact that the Ivoirian gendarmes then required all suitcases to be taken off the bus and opened up for inspection. Gendarmes rifled through the suitcases, and retrieved some electronic gadgets (presumably flashlights), and a knife here or there or so (though not obviously intended as a weapon and perhaps as a utensil). They confiscated anything they thought suspicious, and then allowed us to repack and place our things back on the roof of the bus.

After this lengthy inspection, we were authorized to proceed southward. Our next brief stop was while passing through the larger town of Abengourou, where the chief of party placed another call to the Ghanaian embassy in Abidjan. We finally around 10:00 p.m. at the Commissariat de Police in Abidjan. After some preliminary inspection of passports and relevant i.d. papers, the chef de police authorized the Ghanaians to continue on their way in their bus to their nightly hotel accommodations. Our plan was to go to the Youth Hostel in Abidjan, in the Plateau section of town, for which we had obtained an address, though not a reservation.

Within minutes of the departure of the Ghanaian bus, the chef de police declared, for security reasons, he would not release us from his station. He contended that since we did not leave with them, this must have been a conspiracy to foment civil unrest. Surprised and a bit alarmed, we requested authorization to speak with someone from the U.S. embassy, who arrive around 1:00 a.m. to request our release under his supervision. The chef de police would not do so until the Ghanaians send down all of the teachers with the ambassador to clarify the plans of the respective groups. Finally, we were released around 2:30 in the morning. The U.S. consular officer offered to drive us to the youth hostel, where we promptly collapsed from exhaustion after a very long day.

Next day, we woke up to see a quite modern city with new roads and buildings almost everywhere, a contrast to the winding roads of Addis and Lagos. Before we took our tour of the city, we found a local French bakery nearby, where we could have breakfast. To the surprise of the bakery manager, we ordered several trays of croissants, éclairs, and other pastries, which we promptly inhaled in short order. Customers in the bakery thought we had not eaten in weeks, to which we promptly affirmed by our gestures.

After our tour of the city, we went swimming at the local Atlantic beach. There, Tish and Judy got caught in some rip tides. Local swimmers quickly came to our rescue, after which we headed to a local health clinic to help in recovery. It turns out that a nurse wound up retrieving a small fish from an ear, and which set us aright for resuming our travel. Being on our way meant taking an Air Guionée Ilyushin jet plane briefly to Conakry, Guinea, and from there a flight back to Lagos.

Once in Lagos, we went eastward to visit another Peace Corps volunteer teacher, Greg Morrison, who had trained in the Peace Corps at UCLA at the same time as we. and Greg was stationed at Ikoti Ekpene, not far from Port Harcourt in the southeast of Nigeria. We had a good visit with Greg, who regaled us with stories post-training and his assignment in Nigeria. We then returned to Lagos where we took a trip up to Ibadan, then Nigeria’s second largest city. We managed to negotiate a few sculpture pieces, one of which I still have. I recall that I spent nearly one whole day in negotiating the purchase, and as elsewhere in my travels, learned how important commercial negotiations are intertwined with social interactions that lead to a mutual level of trust and friendship.

From our return trip to Lagos, we then flew back to Addis, content that we had seen a bit of West Africa that remained with us thereafter. Once back in Addis, we shared our experience with fellow volunteers Dick Coolidge, Ron Kaley, Ken Sheppard, and others, many of whom had taken charter flights to the Middle East and had similar tales of adventure to recount. With our trinkets on display, this reunion was something like an improbable meeting of Henry Morton Stanley and Lawrence of Arabia, seeing each other for the first time.

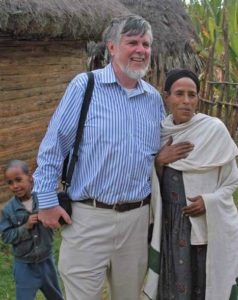

Phillip LeBel (Ethiopia 1965-67) was stationed in Emdeber for two and a half years, and completed a third year (1967-68) teaching secondary school history under a contract with the Ethiopian Ministry of Education. He has traveled to Ethiopia several times, most recently, teaching a month-long course at Wolkite University in October 2017, and has published articles on Ethiopia in addition to others in his discipline. He is Emeritus Professor of Economics from Montclair State University in Montclair, New Jersey and lives in Delmar, Maryland.

Photo taken by Charlie Ipcar (1965-68) with former landlady Woyzero Atsede, in February 2009. She was still living when seen on LeBel’s Wolkite University visit in October 2017, fifty years after first stay in Emdeber, Shoa province.

Having done my own extended travel when I left my PC job in the Philippines in 1963 and traveled through much of West Africa in the late 70s and early 80s, I enjoyed reading about your travels. Thanks for sharing them. Parker W. Borg (PC Philippines 1961-63) and State Department Director for West Africa (1979-81).

What a great adventure to tell! Hopefully, it will inspire others of us RPCVs to write of our off-post adventures from those PC daze, …er, days. It has given me some ideas, though in Nepal back in the 1960s it was trekking in the Himalayas that kept us entertained on holidays. Internationally, some of us tripped through north India, and/or visited the beaches of Thailand.

That is such a good idea. This telling thrills me. Such a lively recounting leaving this reader wishing for more. John Coyne & Marian Haley Beil (and her techie genius son) & Joanne Roll and others also are the good conduit-demons waving-on news information and tales and the dream, our dream as it has spread into 6 decades now.

Anyone who enjoyed reading about this adventure, must get his or her hands on Geraldine Kennedy’s HARMATTAN: A JOURNEY ACROSS THE SAHARA. it’s the story of five women Peace Corps Volunteers who crossed the Sahara in 1964. It’s one of the great Peace Corps memoirs.

BTW, John, I didn’t find Geraldine’s name on your list of RPCV writers.

Very enjoyable read. Thanks, Mark Jacobs

Anyone who enjoyed reading about this adventure, should get his or her hands on Geraldine Kennedy’s HARMATTAN: A JOURNEY ACROSS THE SAHARA. It’s the story of five young women Peace Corps Volunteers who crossed the Sahara in 1964. It’s one of the great Peace Corps memoirs! Not to be missed.

BTW, John, I didn’t find Geraldine’s name on your list of Peace Corps writers.

When you hit West Africa this amazing journey reminded me of Graham Greene’s, “Journey Without Maps”, my totally favorite travel novel. My five month journey was through most of Latin America which I included in my book, “Different Latitudes: My Life in the Peace Corps and Beyond”–those post Peace Corps trips, once you’ve got some language and cross cultural skills, can be the most productive and fun parts of the Peace Corps experience! Thanks for including the maps! Mark

Marnie: Geraldine’s book is included in Peace Corps Bibliography.

What an incredible journey in the sixties! Can same be done today, is my question? I revisited Turkey twice in the 1990s, even led a tour, and visited our villages. But in Turkey, for example, it is dicier to visit some areas, due to the Islamist President that sows hatred of foreigners, since a supposed US-backed coup –eg, Americans (wasn’t true, but Embassy warns against traveling outside Turkish cities, at the moment). H. Green, Turkey V