SWAHILI ON THE PRAIRIE — Talking with David Asher Goldenberg (Kenya)

NOTE: I urge you to read this insightful interview and watch Dave Goldenberg’s wonderful documentary, Swahili on the Prairie. This film is what the Peace Corps has been about all these years. While this is not your story, it is your story. All of us where there. All of us went overseas to countries we could hardly find on a map and came home with stories to tell. We came home having done a job no one expected we could do. We came home with friendships made and friendships that continue today. We are the Peace Corps. We are the legacy of JFK and the New Frontier. We are what America is all about. Read Marnie Mueller’s wonderful interview of David Asher Goldenberg and his insightful film Swahili on the Prairie. Yes, it is about these guys who went to Kenya to work on farms, but it is also about 200,000 of us who for nearly 60 years have said to ourselves “I can do this. I can make a difference.” And we have. — JC

Filmmaker David Asher Goldenberg (Kenya 1968-70) speaks about the making

of his documentary, Swahili on the Prairie, with Marnie Mueller (Ecuador 1963-65)

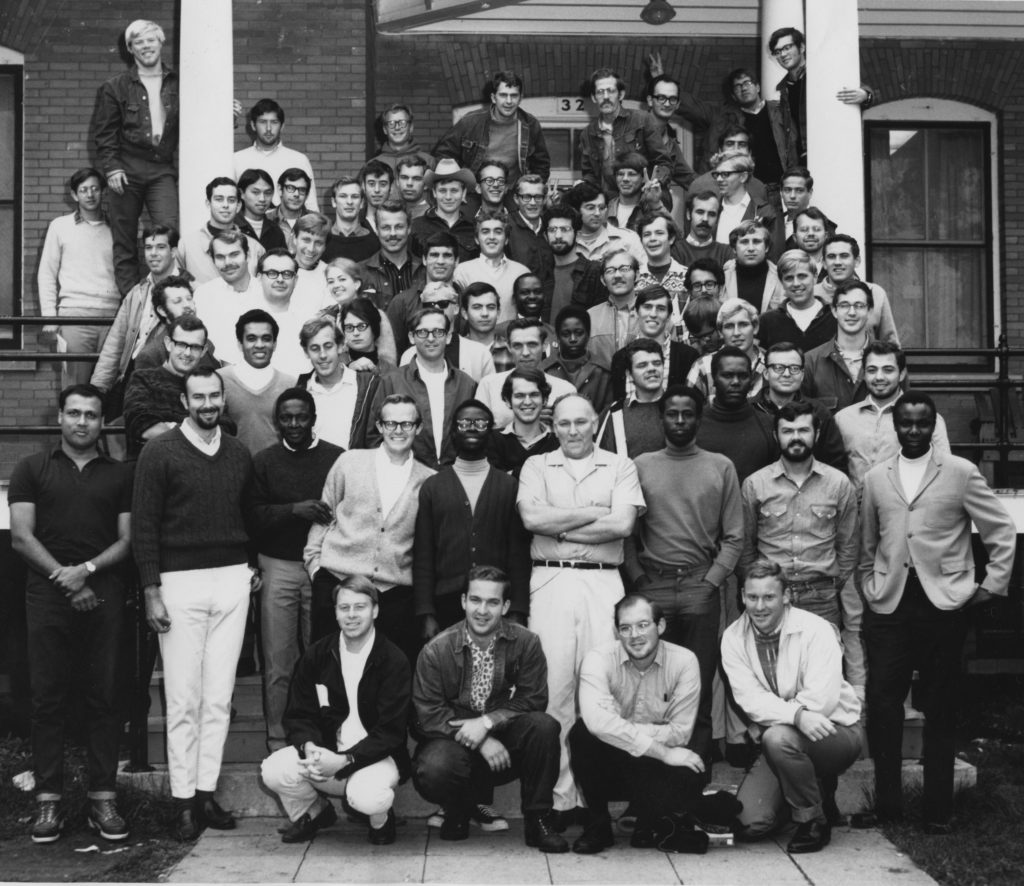

Kenya PCVs 1968–70

Marnie Mueller: People who have read my writing about the Peace Corps in general and my own experience, know that I’ve been ambivalent about the efficacy of the program and its impact or non-impact on the world and even on the United States. But viewing the new documentary, Swahili on the Prairie , and thirteen shorter docs and outtakes from the film, have significantly altered my view. By the end of watching the stories of 24 of the 49 young men who trained and went to work in Kenya in 1968, I found myself being proud to have been a Peace Corps Volunteer, amazed by what they had accomplished, what they had contributed to the development of a newly independent African country, and what they went on to do after their time in Kenya. This is a film that depicts an early outstanding training program on the plains of North Dakota that lead to significant work projects in Kenya. It is the opposite of hagiography in its openness to the complex mix of commitment to making a better world, to using the Peace Corps to avoid the draft, to depicting sometimes risky and rambunctious young male behavior, all coupled with the intense work ethic these Volunteers applied to their jobs.

The film is unusual in that it was filmed and produced by one of the men of this training group, David Asher Goldenberg,  who has generously agreed to be interviewed about the making of the film and the experience of looking back on his training as well as his time in Kenya.

who has generously agreed to be interviewed about the making of the film and the experience of looking back on his training as well as his time in Kenya.

Now we hear from David.

Just before sitting down to reply to your questions I went out for a long walk in my neighborhood. I was actually researching the route of an old trolley line for another project. And there in the middle of a 1950s suburban street was this memorial marker. The day that this 19-year-old was killed, we were winding down training and sweating out whether we would be “selected” to go to Kenya or have to face the draft.

Can you tell us what the impetus was for making this documentary so many years after the experience? Many of us waited for 25 years before we could put pen to paper about our experience, but in your case, it was 50 years before you began filming.

There were two factors. Our group had had two previous reunions, but none since 1993. As we began planning the reunion, I decided that I wanted to capture people’s memories on film.

Concurrently, during 2017 and 2018, there were numerous retrospective films and articles about Vietnam and the events of 1968. I realized that when we had gathered in Bismarck, North Dakota in July, 1968 we stood at the confluence of critical historical movements, nationally and internationally. There was also the oddity of the training site. Why were we learning Swahili in Bismarck? How was living with Sioux families supposed to prepare us for the Kikuyu and Luo people?

The second factor was that I didn’t begin making documentary films until about 2000.

How did you locate your fellow group members? What were their feelings about recalling their experiences?

The exercise of tracking down our group members deserves its own documentary. Some of us had kept in touch with a few others through the years. To track down the rest, one member of our group, Alan Johnston, became an expert human bloodhound. We had the booklet from the beginning of training that provided home addresses in 1968 and the colleges we had graduated from. Using an online search service, Alan was able to find a number of people. He also approached College Alumni organizations. In one case, the individual had changed his entire name, but Alan found him through his brother by using the 1968 address. Searching online for my Bismarck girlfriend, Cheryl, I found an obituary for her husband and then I contacted her through Facebook.

We also tracked down some our Bismarck trainers and our assistant director from Kenya. Many of our trainers were mythic figures themselves. Tom Katus (who appears in the film) was a member of the very first PC group: Tanganyika I. Our Assistant Director, John Riggan, had a long and storied PC career. Some of our Kenyan language trainers went on to be members of Kenya’s parliament and high government officials. I tried to locate them, but many were deceased.

Almost everyone was willing to participate in the interviews. There was only one refusal. Another refusal relented when I was in his area.Geography had a lot to do with who was interviewed. I started with those who lived near me in New England. Chuck Howe, a farm boy from Connecticut, had stayed five years in Kenya and had practically no contact with the rest us or with PC staff. We found an address through the voter information for his original town, so two of us just drove there unannounced. Despite not having seen each other for 50 years he was very matter of fact about our appearance, but I had to come back months later for an interview.

Then there was a trip through Philadelphia, the DC area, and Delaware. Finally, I flew to Texas and Jack Diffily and I covered 2,000 miles for interviews in New Mexico, Arizona, and California. Of course, in doing this, I was having my own personal reunions.

How did you avoid getting set pieces of storytelling because most of their recollections feel spontaneous and filled with emotion?

Clearly there were instances in which individuals were repeating a story they had shared many times during the years, but that was rare. In preparation for both the reunion and the film, I asked everybody to pull out their old photographs and have them scanned. [As a footnote, I should remark that it was during the 1960s that 35mm SLR cameras became widely available. Many group members bought theirs at the Amsterdam airport duty-free shop on the trip to Nairobi.] I doubt that previous PC groups had such an extensive visual documentation. Two of us even had Super 8 footage. Also, to stimulate memories, we asked people to review the letters home that their parents had kept.

I began every interview by asking them to describe their situation and their feelings in early 1968 when they ended up applying for Peace Corps. For almost everyone, this elicited a highly emotional response. Those were such charged times on both personal and political levels. To elicit memories of Kenya I asked people to recall a smell from their time there. For me it was the particular odor of the curdled milk that rural people make – maziwa lala. For someone else it was the wax their servant applied to the concrete floors; for another it was motorcycle oil.

Although we were almost all white, we had incredible diversity in terms of class and background: Ivy Leaguers (several with master’s degrees), geologists, mechanics, and farmers. But as young people in 1968 we didn’t seem to have much curiosity about each other’s family histories. Therefore, I spent quite a bit of time on that subject, with fascinating results.

Why did you make the choice of focusing primarily on the training and the politics of 1968 both in the United States and Kenya at a time the country was moving from colonialism to independence? Could you also speak a bit about what made this training so unusual?

Our reunion was a celebration of fifty years since our departure for Kenya in 1968. The training experience itself was unique. We were on a former calvary fort that had served as a WWII enemy alien internment camp. Our isolation enhanced our language training. Ironically many of us reached our peak Swahili fluency in Bismarck because once we reached our Kenyan destinations, we found we had to tone down the highly grammatical language we had been taught. And the training was our major shared experience. We did see each other in Kenya, but most of us worked in isolation.

Our generation was greatly influenced by the Civil Rights movement and some of us had even participated in it (although I did not cover that in the film). The Vietnam War loomed over us every day during training and later in Kenya. We arrived in Kenya just four years after independence and most of us worked for the Kenya Government ministry that worked to successfully transfer lands from white colonial farmers to African small holders.

I also watched your 13 additional short documentaries about the experiences of your group in Kenya and afterward, coming home to America, and your significant career paths that were informed by having been in the Peace Corp. These are so rich and powerful that they would make a marvelous sequel to Swahili on the Prairie. Have you ever thought of making a follow-up documentary?

The “showcase” containing 13 additional short films about our Kenya PC group is on my Vimeo site. I did use some brief sequences from the shorter films in “Swahili on the Prairie.”

Yes, there is certainly enough material for at least one other film focused upon our time in Kenya. That is my next project and I am challenged by the richness of topics that we covered. At this point I am thinking of trying to convey the extent to which we inherited essentially “colonial” roles in Kenya. We arrived at a point when there were relatively few university-educated Kenyans and we assumed very responsible positions that had been held by members of the British colonial service. It was similar to the experience of young British District Officers in the British Raj in India, but we brought a very different attitude toward it. We were very conscious of our white privilege. We also had to navigate Kenya’s very complex ethnic mix with its multiple tribes, a varied Asian community that dominated business, and the influential remaining European population. Something else that needs to be explored is the risks we took in Kenya. We broke a lot of PC rules even knowing that if we were thrown out, we would still face the draft and Vietnam.

The fact that you were a member of the group added richness to the film for me. Was it difficult for you to juggle the roles of participant and producer? Did the subjective aspect of being a participant make for problems in the editing process?

Yes, this was both a big challenge and a big advantage. It was the first time that I was a subject of my own film. I had to stage my own interview. And in editing, I was very tough on myself, cutting out scenes that would probably have been of interest, but concerned that there was too much of me in the film. Of course, it enriched my approach to interviews because I knew the subject so intimately. I had been to almost all the places where my friends worked in Kenya because my Visual Aids job took me everywhere. Consequently, I could follow up their responses with detailed questions. It should be noted that in Swahili on the Prairie the sequence about our work in Kenya was very brief and accentuated our accomplishments. This was not a universal experience: some water projects failed because of poor design; one highly qualified engineer could not handle the social challenges of the job; and those carrying out agricultural extension were often frustrated by limited achievements.

I understand that you had an early screening of the film in North Dakota. What was the response from the community, especially to the rather humorous sections about the interactions between towns people, the Volunteers, and the Black Kenyan teachers?

We screened the film in January 2020 in both Rapid City, SD and Bismarck, ND. The response was very positive and there were no negative reactions to our portrayal of local people including their racism. I was most gratified that the several Lakota people who came to see the film appreciated it and wanted to show it to young people on the reservation. Two sisters in the Bismarck audience recognized themselves in a couple of photos and shouted out “that’s us!” After the screening we went out to tour the old fort where we had had our training. It’s now the United Tribes Technical College and, unbeknownst to us, our presence in that fort that summer of 1968 played a critical role in preserving the site for the establishment of a college for Native Americans.

What has been the response so far from the Returned Peace Corps community. Have they found a correspondence between the film and their experiences?

It seems that most former PCVs who have seen it thus far have been our contemporaries, and their response has been overwhelmingly positive. I’ve had some very interesting communication with old Kenya hands from other groups, even one who had my job a couple years beforehand. I shared it with a younger audience in the Rhode Island Returned PCV group and many of them were fascinated by different aspects. But some of them displayed a naivete and lack of historical understanding. For instance, they couldn’t grasp why an agriculture and engineering group in 1968 would have been all-male.

I wish you much success with the film. It is a valuable historical, political, and human document of the sort that is an important reminder in these difficult times, of what Americans can contribute to the greater world when carried out with humility, hard work, and good will.

•

David Goldenberg

David Asher Goldenberg grew up in Paris where his father, an economist, was one of the directors of the Marshall Plan in France. After high school in Washington, DC he attended Dartmouth College. Following his Peace Corps service, he drove a motorcycle from Bombay to Paris with a several months’ stay in Israel. David returned to Kenya in 1974 – 75 to conduct research and received his PhD in anthropology from Brown University in 1982. From 1977 – 1982, he was faculty coordinator of a 600-student adult degree program at the University of Rhode Island. Then he returned to international development. From 1984 to 1998, he worked for Plan International, a major child-centered NGO, as director of research, evaluation, and policy. Subsequently, he was a consultant for a number of international NGOs including CARE, Save the Children, Plan International, and InterAction. He has been making documentary films about history, theatre, and local community organizations since 2000.

Marnie Mueller

Marnie Mueller is the author of three novels: Green Fires, The Climate of the Country, and My Mother’s Island, published by Curbstone Press, and currently in-print with Northwestern University Press. She is a winner of the Maria Thomas Prize for Fiction, an American Book Award, The New York Times New and Noteworthy in Paperback, and Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers,and the Marian Haley Beil Award for Best Book Review, among many awards. She is on the steering committee of Women Writing Women’s Lives, a professional biography association.

Click to view Swahili on the Prairie

For reasons that escape me, I was invited to attend the termination conference for this group held in Malindi. I remember none of the details of the numerous conversations, but I have a clear memory of the tone, the feel of those discussions. Intense. A few times angry. More than once, frustrated. Some of this emotion was directed at Peace Corps staff, some at themselves and their work assignments. Frustration with what was accomplished compared with what was aspired? Perhaps. But let me quickly say there was also pride, well-deserved pride.

My other memory was of the water polo game that was played repeatedly over two days. There were no sides, no rules, and no one kept score. But it was intense, like the discussion I’ve tried to describe.

Chuck Coskran

PC/Kenya staff

Very interesting Chuck. I don’t remember the anger. I do remember that we voiced a very strong sentiment that we should be replace by Kenyans in the positions that we were leaving. Partly due to our training, we felt that there were many competent replacements. There was also a suspicion that the Kenyatta government was more comfortable having PC volunteers in these positions than qualified Kenyans who might not be politically cooperative.

This is a wonderful interview. As a participant in the process I can attest that this fully captures the spirit with which this project was undertaken. David’s skill as a documentary filmmaker was in condensing what must have been 30 to 50 hours of filmed interviews into this final one hour story.

Thanks, Marnie, for your interview of David and his work to produce and direct “Swahili on the Praire.” It brought back a lot of memories, plus photos, of our PC training in Bismarck, and our service in Kenya. David is absolutely correct that many of us had very strong sentiments about being replaced by Kenyans. I certainly voiced my opinion with the Department of Agriculture in Machakos, the National 4-K Office in Nairobi, and Peace Corps. I was delighted when Samson Kavoi, a division manager, was selected to replace me at the district level. With his appointment, Samson was able to come to the U.S. to visit and speak with 4-H leaders in the Midwest about their work. It was a trip of a lifetime for Samson, and undoubtedly helped him to carry out his new responsibilities. I would not say there was “anger” about our PCV experience in Kenya. Some of us were somewhat frustrated with PC management in Kenya. On the other hand, we were all relatively young adults, probably unnecessarily impatient when “results” did not quickly transpire. In addition to meeting many Kenyans and volunteers from other foreign countries working in Kenya, as a “generalist,” I had the opportunity to meet, and develop friendships with fellow PCVs from backgrounds different from mine.

I was assigned to Kenya after my initial assignment to Nigeria was cancelled because of civil war and then my Tanzania assignment was terminated at the end of training because of problems between Tanzania and the USA. As I was a South Dakota farm boy with extensive agricultural experience and now basic Swahili, Kenya was where I ended up 1966-1969. I was told to go to the Ministry of Agriculture and find a job. I was sitting outside the office of the Director of Research waiting to be interviewed for work at the swine research station. Then a senior agricultural officer asked me if I was the new PCV looking for an assignment. I said “yes”. He asked me if I knew anything about wheat farming. I told him that I was raised on farm and had planted and harvested a lot of wheat and other grains. I got the assignment which was to establish several (500 acre) farms. I was given a new Land Rover as I had to move my camp to each new location. The tractors and other equipment were very similiar to what we used in the USA. I has about 20 tractors in my unit. When I arrived at the camp I found many implements damaged, mainly minor damage but not functional. I also has a portable electric welder and I was able to repair most of the equipment. The project got off to a good start and then moved the World Bank funded Masai Agriculture Origization. I was then assigned as a area manager for that organization. Two years in Narok on the new wheat farms and one year on the island of Lamu. That Kenya PCV experience set the stage for what I would do in the future. After 3 years of graduate school at Ohio Univeristy I returned to Kenya working again in large scale agriculture and also consulting for development agencies including World Bank, USAID and several European development organizaations. While still in Kenya USAID offered me a mid-caareer appointment as a Project Development Officer in their regional office in Nairobi. I have worked a total of 47 years in Africa and the Middle East.. This would not have happened without the PC experienece . Now I am back harvesting soy beans on my fram in South Dakota. I am so greatful for the Peace Corps experience.

Gregg,

You must have crossed paths with some members of our group. Wish we had known there was a PCV in Lamu in 1969; we would have all descended on you for visits. Did you know George Olesh from our group? He also worked with the Masai for a period on a WB funded project and went on to a career with FAO. Owen Heinrich from our group was from a farm in North Dakota and now lives on the coast in Kenya. They both appear in the film.